Summary

This article challenges the persistent myth that nineteenth-century landscape sketches attracted little public interest and, as a result, were neither exhibited nor collected in their own time. Evidence to the contrary – most notably the regular appearance of such studies in private collections and in exhibitions organised by Kunstforeningen (the Copenhagen Art Society) – reveals a lively contemporary appetite for artists’ working material. That interest ultimately culminated, around the turn of the century, in the formal inclusion of landscape sketches in the National Gallery of Denmark’s collection.

Articles

Over the past decades, the Romantic period’s plein-air studies have been regarded as a milestone in European art history. But how did this taste, this appreciation for studies emerge? A claim often seen in art-historical literature asserts that painters’ studies and oil sketches were not known to the public in their own day, and that the capacity to appreciate such immediate and seemingly unfinished images only arose with the formative experience of Impressionist painting. In the English-speaking world, a narrative arising in recent years claims that it was a small circle of British and American collectors, art historians, and art dealers who, from the late 1950s onwards, ‘discovered’ the hitherto overlooked qualities of early landscape studies.1 Until then, it is alleged, only studies by superstars such as Corot and Constable could be admired and collected, while comparable works by their contemporaries are said to have been ignored. Yet although collectors such as John and Charlotte Gere undeniably made a significant contribution to cultivating a taste for Romanticism’s unpretentious plein-air paintings in, for example, Britain, the reception of landscape studies surely has its own history in the other European nations.

In Denmark, landscape studies were appreciated at an early stage, perhaps even earlier than in most other countries. From the 1830s onwards, even loosely executed landscape sketches were regularly exhibited in Copenhagen and acquired by private art lovers. From there runs an unbroken line through the following generations’ increasingly widespread interest in oil studies, culminating in their eventual recognition by museums. The most obvious example of this movement is the gradual incorporation of such works into Statens Museum for Kunst – the National Gallery of Denmark – in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Accordingly, in what follows the SMK collection will serve as a natural focal point and has supplied most of the illustrations.

Although there is a long and rich tradition for scholarly study of Danish landscape studies from the first half of the nineteenth century, no effort to clarify their historical status has ever been made.2 Instead, the historiographical treatment of the phenomenon has focused on the reception of plein-air studies at the end of the nineteenth century among art historians such as Karl Madsen, Emil Hannover, and Julius Lange.3 Far less scholarly interest has been devoted to the art market and collectors, or, for that matter, to what the period’s exhibition activity, newspaper criticism, and art societies and associations can tell us about the status of this body of studies. The following pages offer a modest contribution to the history of the appreciation of plein-air painting in Europe.

Landscape studies are a broad category, and not one that is necessarily easy for a modern viewer to identify. For contemporaries, however, they seem to have been easier to recognise as something other than a finished work. Of course, the distinguishing traits might concern their style and execution: studies were often painted swiftly and freely, with visible brushstrokes and without the smoothing, laborious finish of exhibition pictures. But this is far from always the case. Even a painting that appears, on the surface, to be fully finished may still be regarded as a study in the eyes and terminology of the period; a fact that requires only a cursory acquaintance with, for example, exhibition and sales catalogues to confirm. Many artists, such as C.W. Eckersberg, were in the habit of continuing work on their studies back home in the studio, without thereby causing these pieces to forfeit their status as studies on a range of other parameters. In some cases, landscape studies are still distinguished by their informal composition, focus or cropping. In countless other cases, they were marked out by their choice of support, typically being painted on paper or on reused scraps of canvas that could never plausibly be presented as fit for sale. In yet other instances, the studies revealed themselves through a particular ‘emptiness’, that is, the absence of human staffage. Or (especially in the 1820s and 1830s) by the presence of a dark, typically black, painted border covering the canvas where it was wrapped around the stretcher, as if to signal that the work was neither intended for, nor deserved, an ornamental frame. Finally, oil sketches often bore a striking, almost carelessly applied date, underscoring that the work had been produced in the course of a single, brief session. Plein-air studies are, in short, a highly varied category which, beyond the method that produced them, share the characteristic of falling outside contemporaneous art-theoretical and art-critical definitions of landscape painting.

The Copenhagen Art Society’s exhibitions of sketches and studies

Since the canonisation of the ‘Golden Age of Danish painting’ in the late nineteenth century, art historians have maintained the view that, originally, only finished pictures could be exhibited publicly, while sketches and studies could not be appreciated as works of art. As early as 1893, Emil Hannover stated in his monograph on Købke that:

The view from the ramparts of the Copenhagen Citadel is the only one of his studies he ever exhibited, for he quickly learnt to distinguish between pictures and studies, exhibiting only the former and, for as long as he lived, carefully withholding from the public the sight of the latter, which he kept on the walls of his bedroom.4

This claim – that studies were kept secret and that there was no public interest in them – is undoubtedly an overly unnuanced reading of the period’s view of art. Hannover’s statement is contradicted quite directly by the Kunstforeningen (Copenhagen Art Society) board minutes of 12 January 1837, stating that the society’s exhibition that week consisted of ‘a number of older works and more recent studies and sketches by Købke’.5 The notion that public interest in studies and sketches belonged to a later period is, as will become clear, a truth in need of significant qualification.

The annual juried academy exhibition at Charlottenborg in Copenhagen was indeed dominated by finished gallery pieces, and as one reviewer observed in 1841, it was ‘generally not (…) deemed appropriate for mere sketches to be hung, except where they show an interesting composition’.6 When the word ‘study’ occasionally appears in catalogues from the Charlottenborg exhibition, it is usually not used in the sense of a preparatory study, but rather as the academic term for a work that was not a free composition but was, in principle, based on observation. This might be a figure or a landscape rendered more or less faithfully, but certainly in a finished state and suitable for sale. Only rarely did genuinely informal study material appear, and not in any real measure until the late 1830s. By contrast, Kunstforeningen, founded in 1825 as a meeting place for Copenhagen citizens with an interest in art, was the venue used to exhibit drawings, oil studies and other actual preparatory works (such as fig. 1). In the initial discussion of the society’s statutes, the following note was made regarding Kunstforeningen’s presentation of preparatory works:

1) At the weekly gatherings, information should be conveyed about everything pertaining to art, so that these gatherings may be regarded as the central point for all news on artistic matters. 2) One should, in a liberal spirit, express one’s opinions about the young artists’ drawings, plans, sketches, etc. 3) Each person should endeavour to procure materials that can provide topics for conversations on artistic matters, by laying out for inspection engravings, drawings, models, or other such things […].7

Many artists even chose to exhibit their studies before they had been translated into finished pictures, meaning that for the society’s members the weekly displays from October to May offered an important way of keeping abreast of the artists’ current activity and forthcoming works.

To see how extensively painted studies and sketches featured in the society’s exhibition programme, we may run through a single season’s displays. For the sake of symmetry, let us take the winter season of 1841; that is, just a few months after the reviewer quoted above had judged sketches unwelcome at Charlottenborg. Just a week after the season opened in October, members of Kunstforeningen could see ‘four flower studies by Prof. Jensen’, ‘A study for Adam Müller’s larger painting: Valdemar the Victorious and his Son in Prison’, as well as ‘a number of landscape studies by F. Rohde and Carmiencke’.8 In late October there were ‘studies and sketches from the summer of 1841 by Gurlitt, from the regions of Silkeborg, Sophiendal and Rye’.9 In February 1842, it was Gurlitt himself who had selected a group of oil studies by fellow artists such as Buntzen, Bendz, Küchler, Sonne, Rørbye and Adam Müller.10 The following week, the art collector Michael Raffenberg presented eight ‘studies in oils by Marstrand, after heads and full figures in Italy’, along with four ‘landscape studies in oils by Carl, Mohr, Fearnley and an unknown [artist]’.11 One of April’s exhibitions comprised ‘23 painted studies by Sonne’ in addition to ‘two painted studies by Roed, depicting the exterior and interior of Ribe Cathedral’ (including fig. 2), and finally in May members could admire ‘nine painted studies from Funen and Jutland, by D. Dreyer’.12 When these entries are compared with the works in question, it is clear that the term ‘study’ is being used here in the narrower sense in which we employ it today; that is, to denote artists’ preparatory and working material.

The summary descriptions above suggest a lively interest in artistic preparatory work in general, and in landscape studies in particular. Much the same picture emerges if we consider individual artists’ participation in Kunstforeningen’s exhibitions over the years. Louis Gurlitt, one of the exhibitors in the season just discussed, had already begun showing his oil studies at the society in February 1835, and subsequently did so again in, for example, 1839, 1840 and 1849.13 Christen Købke held his first solo exhibition in January 1837, which, as mentioned, included a number of painted studies, and a few months later Fritz Petzholdt arranged an exhibition of Italian studies and sketches.14 Petzholdt’s display was reviewed in the society’s short-lived organ Dansk Kunstblad, and the reviewer singled out a ‘particularly enchanting […] view of the district around Olevano, where one looks down into the beautiful valley – lit by Italy’s glowing rays of sun – through a pergola (espalier or arcade-walk)’. This painting must be identical with one now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago [Fig. 3], a fresh evocation of southern light, but without the carefully worked-over finish and added staffage of the completed, saleable pictures.

The qualities of study material

Perhaps the best example of Kunstforeningen’s exhibitions of preparatory work is provided by Kunstbladet’s thorough review of Martinus Rørbye’s exhibition in February 1838. The show comprised a large number of studies and finished works from the artist’s recently completed journey abroad, including loosely executed oil studies.15 The exhibits considered suitable for display even included the ‘swiftly sketched’ study of two yoked oxen [Fig. 4], painted in great haste on a sweltering June day in the Roman Campagna and, despite its rather rough and unsophisticated execution, suitable for being singled out as a characteristic animal study.16

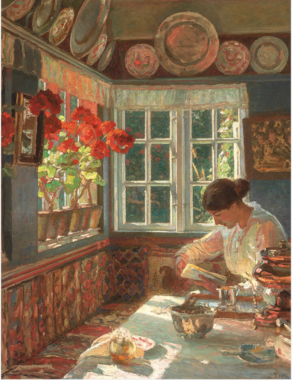

Likewise deemed fit for exhibition was a freely sketched nocturne from Procida, in which Rørbye, with his customary observational zeal, set down the memory of a sight familiar to all Danes, here set under foreign skies: a Midsummer bonfire (the work is now in the collection of Ribe Kunstmuseum). Most of the landscapes and townscapes shown, however, were more fully worked – though often executed on paper, which in itself was enough to signal their status as mere study material. This was the case, for instance, with the light-filled study of the square in Amalfi [Fig. 1], which was a great success at the exhibition and earned Rørbye a commission for a larger version.

Through exhibitions of this kind, Kunstforeningen contributed, throughout the 1830s, to foster an awareness of the qualities of studies among the art-interested public. One of the purposes of exhibiting works such as those mentioned above was evidently to open members’ eyes to the studies’ greater sense immediacy, and to how much of this trait was sacrificed in the subsequent artistic reworking to produce the saleable piece. Unfortunately, the society’s board, or those responsible for the exhibitions, never expressed their motives or ambitions in writing. Yet the theme was occasionally taken up in press notices about the exhibitions, which can reasonably be read as reflections of members’ discussions at their meetings. When, in February 1843, the society showed some figure studies for an altarpiece by Adam Müller, the reviewer in Journal for Literatur og Kunst (it appears to have been the art critic K.F. Wiborg) wrote:

As is sadly so often the case with artists, so it has happened to M. here too: the study, made directly after nature and animated by all the divine freshness of the first flush of enthusiasm, expresses something far more beautiful and noble, and is painted with far greater virtuosity in the pale, downward-cast half-profile, compared to the Apostle Luke in the finished picture.17

Only a month later, the same reviewer had occasion to repeat his view of the qualities of studies when Kunstforeningen, in March 1843, exhibited a number of ‘landscape studies by Dreyer’:

Among these we found, in the study of a sunlit bridge [Fig. 5], welcome proof that this artist is indeed capable of what one had previously, to some extent, doubted – namely, of wresting from nature its immediate beauty.18

The comparison between immediate studies and worked-up works of art did not, however, always fall in the former’s favour, as was the case with a landscape sketch and a study of a head by Ernst Meyer, ‘which further convince us that this artist has greater virtuosity in carrying through [a work] than in casting it swiftly upon the canvas’.19

Supporters and collectors in the 1830s and 1840s

An intriguing, and obvious, question presents itself: how did this interest in sketches and studies become established within Kunstforeningen? Fortunately, the society’s board minutes often record the actual organiser of an exhibition by name, and on that basis we can observe that it was mainly artists who incorporated sketches and studies into the shows they themselves arranged. The reason was probably, in part, that artists were already accustomed to handling study material and discussing it among themselves – but presumably also that they had a vested interest in disseminating knowledge of their own and others’ working methods and ambitions. Of Kunstforeningen’s major solo exhibitions, the Købke exhibition mentioned above, in 1837, and Rørbye’s exhibition in 1838 were both arranged by the sculptor H.E. Freund.20 Gurlitt’s exhibitions in 1835 and 1839 were organised by Eckersberg and Hetsch respectively, while it was the flower painter J.L. Jensen who, in 1845, mounted a retrospective exhibition comprising twenty-eight paintings by J.C. Dahl from the period 1812 to 1844.21 Many other sketch exhibitions were, unsurprisingly, put together by the artist in question: Eckersberg, J.L. Jensen, Jørgen Sonne and H.W. Bissen were among those who would readily bring their own preparatory works when it was their ‘turn’ to arrange an exhibition organiser.

Even if artists were evidently more than willing to exhibit preparatory works, whether their own or others’, the society’s members in general must also have possessed alert artistic sensibilities in order for such works to be deemed relevant for display at all. The spread of this taste can be illustrated by considering the lawyer and civil servant Christian Frederik Holm (1796–1879), who joined Kunstforeningen’s board in 1830. He subsequently sat on the society’s art committee from its establishment in 1831 until 1834 and returned to the board in the years 1838 to 1842. Alongside this post and numerous other positions, Holm also served as archivist to the foundation known as Fonden ad usus publicos, a role that brought him into contact with countless artists, poets, musicians and scientists of the period. Today, Holm is perhaps best known for commissioning a portrait of his three children from Eckersberg (now in the Hirschsprung Collection). He also collected prints, but more interesting in the present context is the fact that as far back as in the 1830s, Holm also acquired painted studies and sketches.22 A list from 1860 unfortunately includes only fifteen of the collection’s oil paintings, among them sketches by Fearnley and J.C. Dahl.23 The collection must, however, have been far larger, and oil sketches appear to have been something of a speciality for Holm. His reputation as a collector is apparent from a remark by Martinus Rørbye. The occasion was a study of a loggia which Rørbye had painted on his first journey to Italy, and which he brought with him on his second trip in 1839–41 [Fig. 6]. In November 1840 he wrote in his diary: ‘Today I began drawing in preparation for a small painting for which I am using the study of the loggia on Procida, before I intend to send it to Holm; he has my promise in this regard; I would certainly not give my studies to anyone else.’24

Holm represents the group among the leading members of Kunstforeningen who knew very well how to appreciate artists’ studies and sketches, not only as interesting objects of study but also as desirable works of art. Nor was Holm alone in collecting painted studies and preparatory works, and other artists were more willing than Rørbye to part with their sketches. Similar pictures could be found in other private collections, such as the ‘sketches and studies by Bendz, Sonne, Küchler, Sødring, Buntzen, Wulff, Petzholdt, Morgenstern and Crola’ which Gottlieb Collin (1806–86) lent to the society’s exhibition in March 1836.25 And in 1843 Baroness Stampe was able to lend a couple of sketches by J.C. Dahl, one of which had apparently been painted in the space of a mere fifteen minutes as a demonstration of the landscape painter’s technical prowess [Fig. 7].26

All these collectors of study material had exceptionally close ties to the artistic milieu, and these connections were the one thing enabling them to acquire small works that had not yet found their way onto the market. In this early phase of the appreciation of study material, it therefore seems to have served, to some extent, as affectionate gifts between friends, yet the activities of these collectors and the society’s exhibitions meant that the taste for immediate preparatory work gradually won wider currency. By the end of the 1840s, this taste had become firmly established within a broader circle of Denmark’s art collectors and connoisseurs.

As an example of collectors who (very likely encouraged by Kunstforeningen’s exhibition activity) began to take an interest in landscape studies, we might mention the merchant Nicolai Gerson (1802–1865). From at least the early 1830s, Gerson collected paintings, and one of his first important purchases came about in January 1834, when he acquired the small study from the ferry landing at Kallehave which Eckersberg had begun on site in late July 1831 and completed back in his studio a few days later [Fig. 8].27 A month later, Gerson returned to Eckersberg and this time bought a small seascape study on tinplate, executed on a voyage with the corvette Najaden the previous summer.28 During the 1830s and 1840s, Gerson’s collection grew to include landscape studies by, among others, Albert Küchler, Constantin Hansen, Vilhelm Kyhn, Emmanuel Larsen, Fritz Petzholdt, and P.C. Skovgaard.29 He owned, for example, a loosely executed study by J.C. Dahl from the cliffs of Møn (presumably identical with fig. 9).30 In December 1850, Gerson lent a number of his studies to an exhibition at Kunstforening, to which Eckersberg also contributed some Roman scenes.31 This, in turn, led to Gerson’s being given, a few months later, the opportunity to buy one of these coveted studies; works which the professor was otherwise reluctant to part with.32

Sketches and studies in the wider public around 1848

The year 1848, when revolutions were fermenting across Europe, proved decisive for Danish art history and, not least, for the dissemination and appreciation of painters’ oil studies. During the first eight months of the year, three of plein-air painting’s most important practitioners – Christen Købke, J.Th. Lundbye and Martinus Rørbye – had all died. The subsequent auctions of Købke’s and Rørbye’s remaining paintings set their sketches and studies in circulation, thereby laying the groundwork for the later process of canonisation. Not all painted sketches found buyers, and the artist’s standing was crucial in determining how valuable the material was considered to be. At the auction of Købke’s estate in December 1848, those who turned up to acquire his studies and sketches were almost exclusively artists – though Raffenberg did secure a Danish landscape study and an Italian beach scene. When the estate of the seven-years-older and far more established Academy professor, Martinus Rørbye, went under the hammer three months later, we find, by contrast, numerous wealthy men and large landowners among the buyers. On this occasion the auction record was adorned with venerable names such as Scavenius, Moltke, Sehestedt-Juul, Raben-Levetzau, Danneskiold-Samsøe, Bruhn, Juel-Rysensteen, Zeuthen, and Holsten-Charisius [Fig. 4]. Rørbye’s studies and sketches had, in other words, immediately become coveted collectors’ pieces for the wealthy elite and, shortly after his death, hung in stately homes such as Gjorslev, Bregentved, Ravnholt, Beldringe, Gisselfelt, Krogerup, Lundbæk, Tølløse Castle, and Holstenshuus.

Between Rørbye’s death and his auction, another significant event in the history of the appreciation of oil studies took place. On 18 September 1848 Thorvaldsens Museum opened to the public, and among the sculptor’s collection of paintings visitors could now admire landscape studies by artists such as Carl Gustav Carus (1789–1859), Franz Ludwig Catel (1778–1856), C.W. Eckersberg, and Thomas Fearnley [Fig. 10]. These were the first studies of this kind to be presented in a public collection. A different situation applied in the Royal Collection of Paintings, much of which was displayed in the Royal Picture Gallery at Christiansborg Palace and, in the new democratic reality, would form the cornerstone of the nation’s art collection. The recently deceased king, Christian VIII, had been a prominent arbiter of taste in his dual capacity as an art-collecting crown prince and as the formal head of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Yet acquisitions for the Royal Collection of Paintings had not changed greatly during his reign, even though privately he had taken an interest in artists’ sketches. His own collection of paintings – which, like the Royal Picture Gallery, was carefully conceived to provide an overview of the history of painting – thus also accommodated a number of more informal oil studies. Among them were Wilhelm Bendz’s study of a carriage gateway in Partenkirchen [Fig. 11], a Neapolitan coastal study by J.C. Dahl, a couple of Eckersberg’s Roman prospects, and Georg Hilker’s study created on the occasion of the Academy’s landscape-painting competition in 1833. On His Majesty’s birthday in 1832, his wife, Princess Caroline Amalie, even delighted him with a study by Eckersberg, which the prince noted with satisfaction was ‘painted in the forest’.33

With interest in landscape studies having reached as far as the monarch, one might expect such pieces to appear among the acquisitions made for the Royal Collection of Paintings as well. However, the two collections were aimed at different audiences, and the official line was set by the gallery inspector N.L. Høyen, who focused on public education and opposed anything sketch-like in art. In his criticism and teaching, Høyen railed against visible brushstrokes, which in his eyes were evidence of inadequate technical skill or even an outright, deliberate insult to the public. To present the people with the imperfect was a serious matter, particularly at a time when cultivating a general appreciation of art was regarded as crucial to the perfection of Danish craftsmanship and industry. In the Royal Collection of Paintings, the appreciation of artists’ informal oil studies thus developed rather more slowly than among collectors and among Kunstforeningen’s well-to-do members. But in 1848 a thaw set in when the royal painting collection, somewhat by chance, received its first true landscape study. The archaeologist P.O. Brøndsted (1780–1842) had, in his will, bequeathed to the king his small painting collection, which included a beautiful study by Catel depicting the Temple of Concordia at Agrigento.34 In this way the door was, if not thrown wide open, then at least prised ajar, enabling more landscape studies to follow. Six years later, three of Eckersberg’s Roman views were purchased at the auction of his estate, and in 1862 the collection acquired its first oil study by Lundbye [Fig. 12]. In the latter case, Høyen could at least reassure himself that this was a finished – he uses the term ‘udført’, meaning ‘executed’ – study which, like Eckersberg’s prospects, did not suffer from what he regarded as a common failing of studies: an inadequate degree of finish.35 Yet studies they certainly were.

Collectors’ interest in the 1850s and 1860s

Private collectors continued to acquire landscape studies with great eagerness in the third quarter of the century. In 1874, for example, the organist Rasmus Claudius Rasmussen (1820–1904) owned studies by Eckersberg, J.P. Møller [Fig. 13], J.C. Dahl, Rørbye, Küchler, Frederik Sødring, Købke, Marstrand, Adam Müller, Lundbye, and Vilhelm Kyhn.36 While connoisseurs such as Rasmussen would assemble a broad selection of landscape studies around this time, it was still by no means a given that works of this kind were valued by collectors and the public at large.

For example, Købke’s small studies found no eager buyers beyond a narrow circle of fellow artists. Even Rasmussen’s contemporary and well-informed fellow collector, the merchant Theodor Kastrup (1820–80) – who, throughout the 1850s and 1860s, built an extensive collection of landscape studies – owned none by Købke. This despite the fact that Kastrup was actually present at Købke’s auction in 1848 and made his first art purchases there. The plein-air animal study by the painter Holm that he bought from Købke’s estate was soon joined by four small landscapes by Eckersberg, two by Rørbye (including fig. 1), one by Bendz [Fig. 14], eight by Lundbye, and a number by P.C. Skovgaard and C.A. Kølle.

Købke’s landscape studies were not the only ones conspicuous by their absence from Danish collections. The same held true of studies by Schleswig-Holstein painters, who were to a large extent regarded as too strongly influenced by Germany and therefore un-Danish. In the wake of Denmark’s war trauma of 1864, the still-young discipline of art history contributed to the nation’s moral reconstruction by establishing the narrative of a Danish school of art, in which Eckersberg was placed on a pedestal alongside his Danish pupils. The German-influenced vein in Danish art (or whatever might be perceived as such) was, by contrast, considered an insignificant offshoot from the main trunk. This perspective also asserted itself when, in 1876, Denmark’s two national art collections were presented with a larger group of landscape studies.

Bravo!

In early May 1876 news arrived that the Danish consul in Rome, Johan Bravo (b. 1797), had died. In his youth he had trained as a painter at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where he became close friends with figures such as Ernst Meyer, H.W. Bissen, and Ditlev Blunck. From 1827 he had lived in Rome, where he soon laid down his brushes and instead became a fixture within the shifting colony of Scandinavians. Bravo became a particularly familiar figure in the Danish-German artistic circles around Bertel Thorvaldsen, whose collections and personal effects Bravo was responsible for dispatching back to Denmark. Presumably inspired by Thorvaldsen’s example, Bravo, before his death, set down the wish that his own art collection, too, should pass to the Danish nation.

The task of inventorying and packing Bravo’s estate was entrusted to a number of painters who were already in Rome at the time. The heaviest burden fell to the future museum director Pietro Krohn (1840–1905), who by then had been living in the city for six years and must surely have known Bravo well. Being Købke’s nephew, Krohn was hardly unfamiliar with the aesthetics and appeal of studies – and a few years after his return to Denmark he found himself a wife who, being the niece of Nicolai Gerson, had even grown up with oil sketches on the walls. The precise contents of Bravo’s collection are difficult to establish today, for in his will he permitted a nephew, the merchant Edouard Brauer of Rotterdam, to select works for himself before passing on the rest to the Danish nation.37 Hence, in Bravo’s estate Krohn found only very few of the drawings that the deceased had purposefully collected from Rome’s most celebrated artists.38

Instead, Bravo’s collection of drawings consisted chiefly of sheets left behind by his Schleswig-Holstein or North German artist friends upon their departure or death. This applied in particular to August Krafft, Ditlev Blunck, and Ernst Meyer, all of whom were richly represented and whose works Krohn and his assistant, the painter Albert Küchler, could of course recognise without difficulty. In addition there were a few framed paintings, along with a large quantity of unmounted oil sketches and studies – material of particular interest to the present investigation, but which at the time only complicated matters further. Works on paper officially fell under the auspices of the Royal Collection of Prints and Drawings (now The Royal Collection of Graphic Art) at the Prince’s Palace, but the oil studies were an awkward fit for the museum’s usual distinction between oil paintings and drawings. What, then, was one to do with such an unwieldy collection?

The director of the Royal Collection of Paintings, Otto Rosenørn-Lehn, declared himself willing to take over Bravo’s six framed paintings, which were deemed worthy of inclusion in the Picture Gallery. Thus, three splendid studies by Franz Ludwig Catel came to the gallery from Bravo’s walls, including a study of a lush Italian river landscape [Fig. 15].39 Catel’s pictures might have provided the seed for a collection of landscape sketches in Copenhagen, but this evidently held little interest. In any case, Rosenørn-Lehn did not consider it necessary to have Bravo’s other mounted sketches handed over, since they lacked frames, and the collection therefore preferred to forgo, among other things, an Italian landscape sketch by Petzholdt. As for the unmounted study material, Rosenørn-Lehn even suggested that it might be deposited at Thorvaldsens Museum. In the end, however, this part of Bravo’s collection nonetheless ended up in the Royal Collection of Prints and Drawings, where 138 drawings found a place in the neatly ordered portfolios while the enormous remainder was set aside on account of its ‘poor quality’.40 This so-called ‘Bravo archive’ still contains a large quantity of unknown and in part unregistered oil studies, clearly testifying to avid interest in studies among private collectors and to an equally strong institutional indifference.

As is evident from the above, Bravo’s collection was a mixture of randomly accrued left-behind material and more purposeful acquisitions. Among it all, Krohn naturally found a fair number of Bravo’s own studies, including preparatory works for his somewhat amateurish exhibition pictures The Emissary at Lake Albano and A Street Scene in Rome.41 The unmounted oil studies are, on the whole, of greatly varying quality, authorship, and interest. For convenience, more than a hundred of the oil studies were attributed to Ditlev Blunck in the 1970s, although closer inspection suggests that he can scarcely have executed more than perhaps fourteen or fifteen of them [Fig. 16].42 Overall, a substantial task still remains in untangling the attributions of the oil studies in Bravo’s collection. A study of ruins, for instance, has hitherto been tentatively attributed to Ditlev Blunck, and the site has been proposed to be the Baths of Caracalla or the Palatine Hill [Fig. 17].43 In fact, however, the study depicts the ruins of the largest of the bath complexes at Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, which incidentally appears from precisely the same viewpoint in Fritz Petzholdt’s 1832 painting in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst.44 The artist behind Bravo’s study has not yet been identified. Another study of an Italian woodland scene shows affinities with studies by Fritz Petzholdt and Albert Küchler [Fig. 18]. Three studies of the sky above the mountains were undoubtedly executed by the same unidentified artist [Fig. 19], perhaps from the circle of the Swiss painter Johannes Jakob Frey. Among German artists, Friedrich Preller the Elder (1804–78) contributed a highly finished landscape study from Olevano dated 1829 which – though identified by Krohn – has until now been tucked away without the artist’s name attached.45 One might continue to draw intriguing oil studies from Bravo’s rich trove for a long time yet.

The neglectful treatment of Bravo’s collection is unlikely to have been due solely to its German and Schleswig-Holstein bias. An equally significant reason must have been that, in the 1870s, appreciation of oil studies still flourished best within closed circles and private collections. The Royal Picture Gallery at Christiansborg had, as noted, been created to serve an educational purpose, presenting the public with the finest art and, hence, the finest craftsmanship too. Within this narrative – and with its German taste – Bravo’s collection could scarcely find a place, and his interesting, well-ordered assemblage of landscape and figure studies in oil was disparaged, jumbled together, and all but forgotten.

Institutional acclaim

Private collectors continued to amass landscape sketches with unabated fervour in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The most conspicuous collector was the tobacco manufacturer Heinrich Hirschsprung (1836–1908), who followed in his predecessors’ footsteps in many respects; indeed, many of his most important landscapes came directly from the collections of Nicolai Gerson and R.C. Rasmussen. While private collectors thus competed to acquire informal landscape studies, the management at the Royal Collection of Paintings was slow to grasp and acknowledge the studies’ value. Things only began to shift, little by little, when, in the 1880s and 1890s, Kunstforeningen arranged a series of retrospective exhibitions and published monographic studies that firmly established the canon of the ‘Golden Age of Danish painting’, with Eckersberg, Købke, Marstrand, Constantin Hansen, and Lundbye as its leading figures. From the late 1880s the Royal Collection of Painting Collection began, tentatively, to purchase Eckersberg’s small Italian and Danish landscape studies, while a few landscape studies by Constantin Hansen, P.C. Skovgaard, and Jørgen Roed also found their way into the collection from time to time. But these acquisitions were few, irregular, and reluctant. Although Købke had been properly rediscovered in connection with Kunstforeningen’s exhibition in 1884, the museum would wait a further ten years before buying its first study by the painter [Fig. 20].

Thus, the institutions only came to recognise studies in earnest with some delay. They were eventually prompted to do so by the vast survey exhibition staged in Copenhagen in 1901 to mark the completion of the capital’s new City Hall. The exhibition was an almost endless procession of paintings, many of them small studies by well-known and unknown artists [Fig. 21]. For the public, the press, and specialists alike the show was an eye-opener and the first good opportunity to identify the focal points of the past century’s art. At the same time, it was strikingly apparent that a vast number of the period’s small gems were in private hands. When the newly appointed museum curator Karl Madsen (1855–1938) wrote a short article in August about the rediscovered Dankvart Dreyer, he made precisely this observation a point of criticism:

The City Hall exhibition sheds glaring light on the fact that, in the Gallery’s representation of older Danish painting, there exists, besides other shortcomings, one very significant one. The Gallery has quite rightly felt obliged to acquire those pictures that appeared as the painters’ true principal works; it has, very wrongly, for many years regarded all studies and sketches as trivialities not worthy of consideration. Yet among them one finds much of the best and most significant that Danish art has produced.46

Better late than never became the watchword, and in the wake of the exhibition the museum purchased a large quantity of landscape studies, most of them by Dreyer (including fig. 5), but also others by artists such as Eckersberg, Købke, Lundbye, Skovgaard, Kieldrup, Kyhn, and Kølle. In the decades that followed, Danish landscape studies gradually became one of the museum’s most important fields of collecting, and the small formats gradually displaced the large, finished exhibition pictures in the galleries.

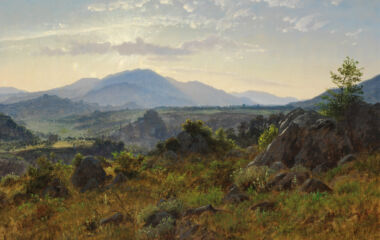

The collecting of foreign plein-air paintings proved less successful: after purchasing, in 1903, an Italian landscape bearing a forged Corot signature, and seven years later two studies with questionable attributions to John Constable, the museum evidently abandoned that path.47 A South German study by the Hamburg painter Christian Morgenstern, which entered the museum in 1914 alongside a Norwegian mountain scene by the Holstein artist Johann Mohr [Fig. 22], would be the last non-Scandinavian landscape study to be added for many years.48 Instead, in 1916 and 1919, the museum incorporated its first studies by J.C. Dahl and Thomas Fearnley into the collection, choices more in keeping with the now clearly intended Danish–Norwegian line in the museum’s holdings of plein-air painting.49

A history of continuity

The history of the appreciation of landscape studies in Denmark is an instructive example of how the past did in fact accommodate more generous and wide-ranging tastes than the period’s art criticism and subsequent historiography would suggest. From being cultivated within a coterie of men with a particular interest in art, the taste for studies spread in widening circles to reach collectors more generally. Admittedly, dogmatic art policy continued to keep landscape studies out of museum collections until the 1901 City Hall Exhibition in Copenhagen finally made it clear that the taste for such pictures had long since become mainstream. One cannot, then, speak of a single, specific moment of sudden, eye-opening rediscovery – and certainly not of such a thing happening in more recent times.50 Unlike in, for example, France, it was rare in Denmark for a painter’s studies to remain hidden in family ownership and reach the art market only after a generational delay. In truth, on Danish soil this scenario applies only to Lorenz Frølich’s figure and landscape studies, which came up for sale only from the late 1970s until the early 2000s, and only then began to do work for his posthumous reputation.51 But that is the exception to the rule; even Petzholdt’s and Dreyer’s studies were dispersed into collectors’ hands before 1920. Hence, Danish landscape studies were never at any real risk of being lost in large numbers, with the possible exception of the unmounted, and thus fragile, studies on paper frequently mentioned in artists’ estates. On the contrary, landscape studies in general were bought and sold, collected, exhibited and valued on a par with – and at periods even ahead of – the finished works. The twentieth century’s shifts in taste and waves of scholarship have not unsettled this time-honoured appetite for the immediacy of the study. Art collectors and museum professionals still enthuse (indeed, as far as the wider world is concerned, with increasing intensity) about the same qualities in the period’s Danish plein-air studies that have been continuously appreciated since the 1830s.