Summary

In response to the climate and biodiversity crises, recent years have seen a renewed focus on plants within science, art and culture. But how may the historical collections of art museums contribute new perspectives? We highlight an overlooked source of new knowledge, topical interest and public engagement in the form of nineteenth-century Danish ‘houseplant art’, which testifies to the arrival of plants in Danish homes and to the intricate entanglement of human and plant life within the domestic sphere. We argue that an interdisciplinary, plant-centred approach to art, combining close and distant readings, can uncover neglected plant histories that imbue these works with fresh, topical relevance.

Articles

A new focus on plants1

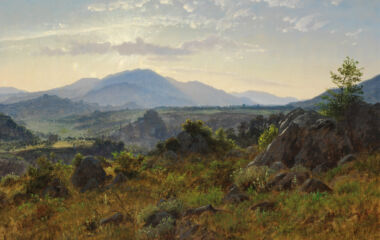

Across the realms of science, art and culture, new attention is being directed towards plants. Three scientists recently published an estimate of the total weight of all life on Earth, showing that plants, with their 450 gigatonnes (Gt), make up by far the largest share of the global biomass while animal species account for only 2 Gt.2 The study highlights the unique position held by plants within the Earth’s biosphere. It reminds us that plants do not inhabit our world; rather, we inhabit theirs. As the philosopher Emanuele Coccia has observed, plants have until now existed on the ‘margins of the cognitive field’.3 We tend to overlook them, or see them only through the functions they serve for us: as timber in the forest, crops in the fields, ornamentals in gardens and on windowsills, or as a picturesque rolling landscape glimpsed from a car window.4 These days, however, global environmental crises of biodiversity loss, pollution and climate change show us that we cannot take plants – and their role in sustaining life on Earth – for granted. These crises compel us to view plants as botanical beings in their own right, and to recognise the complexity of our shared existence with them. In response, anthropologist Natasha Myers has proposed the term as a new, plant-centred starting point for knowledge and design. Planthroposcene is a contraction of ‘plant’ and ‘Anthropocene’, the latter referring to the current geological epoch marked by extensive, human-driven environmental disruption.5 The term ‘planthroposcene’ does not designate an era; rather, it constitutes an epistemic proposition, an approach grounded in the fundamental entanglement of human and plant life. Whereas the notion of the Anthropocene emphasises human (anthropos) actions and their environmentally destructive consequences, the planthroposcene emphasises how plants are co-creative agents of a shared world, not a passive backdrop.6

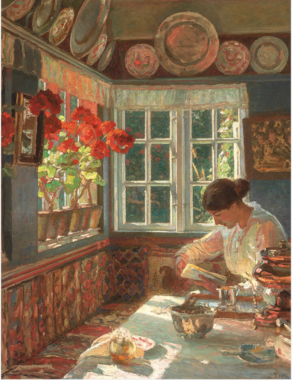

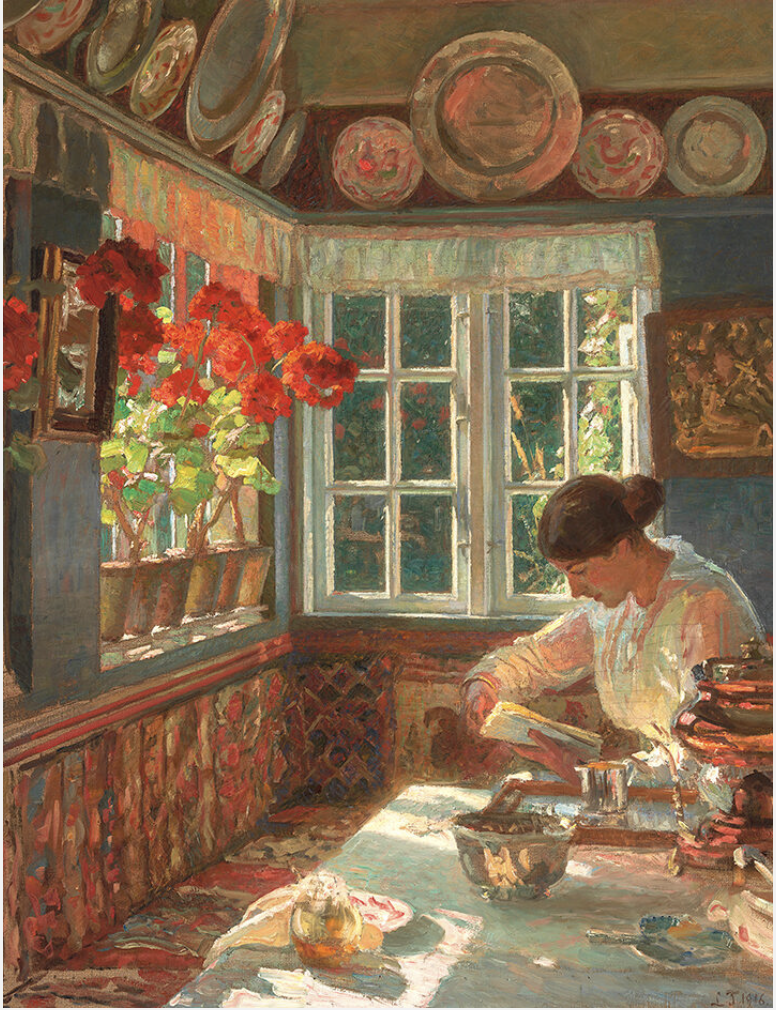

Today, many contemporary artists and designers are creating ’planthroposcene’ spaces for encounters between humans and plants.7 But how may art museums play their part in this green turn? How might they activate the collections they are legally bound to develop, preserve, present and study in order to attract renewed attention to our entangled coexistence with plants?8 This is the overarching question asked by the research and dissemination project Hidden Plant Stories, supported by the Velux Foundation.9 Establishing cooperation between Aarhus University, Ordrupgaard and The Hirschsprung Collection, our interdisciplinary team delved into Danish art museum collections to uncover overlooked plant histories. We have focused in particular on the houseplants which appear as seemingly incidental background elements in many nineteenth-century interior paintings [Figs. 1–4]. To facilitate a systematic investigation, alternating between close and distant analysis, we created a database of 452 Danish oil paintings produced between 1820 and 1920.10

The following article is a position paper – a genre often used in the early stages of natural science research projects to sketch out the field in which forthcoming research and dissemination activities will unfold. Here, we identify nineteenth-century Danish ‘houseplant art’ as an overlooked source of new knowledge about how our lives are entangled with those of plants. We argue that an interdisciplinary, plant-focused approach, alternating between close and distant readings, can pave the way for fresh perspectives on museum collections. This, in turn, may enhance the topical relevance of those collections and underline the role of art museums as essential contributors to our current era’s collective efforts to cultivate new ways of seeing – and new understandings of – the plants with which we live.

</br>

Identifying and studying Danish ‘houseplant art’

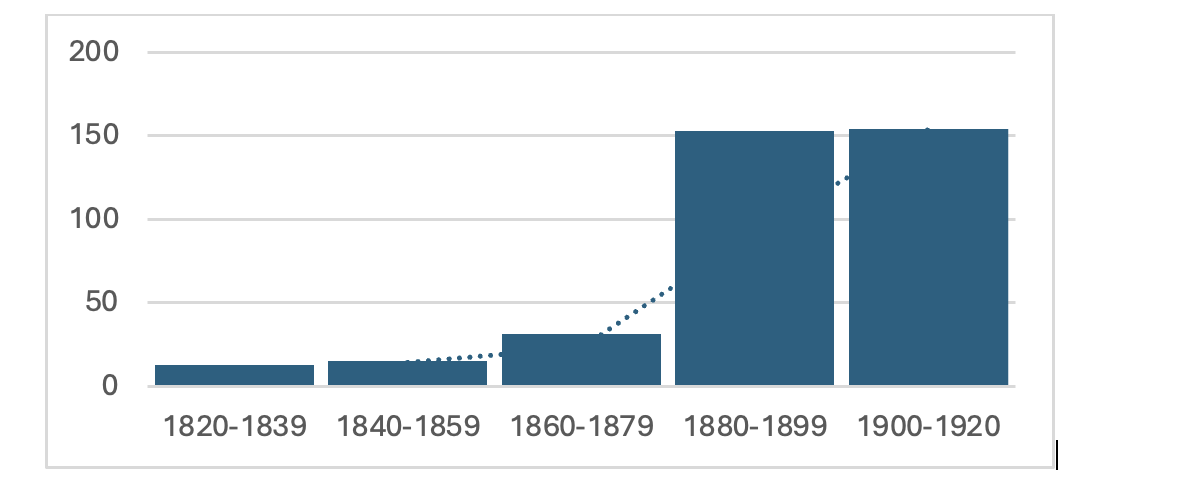

The only criterion for including a work in our specific collection is that the artwork must include a houseplant – defined here as a plant growing within a domestic setting. The collection was assembled through searches in the museum database SARA, supplemented with material from online resources such as Wikimedia Commons, where photographic documentation is often uploaded by auction houses in connection with sales.11 Our focus is the nineteenth century, when the houseplant first emerged as a cultural phenomenon. Given that we did not identify any relevant works from 1800 to 1820, we specifically home in on the period from 1820 to 1920.12 A total of 452 works have been coded using 27 datapoints relating to botanical, cultural, social and artistic factors, based on an initial round of analysis. The resulting database enables us to conduct multivariate statistical analyses of the motifs with a view to uncovering significant patterns. It also allows us to extract simpler information such as data on the increase in the number of paintings featuring houseplants over the course of the century [Fig. 5].

The project alternates between close and distant readings. Quantitative analyses can inform close readings of individual works; for example, an indication of how widespread the houseplant motif was at a given time can offer useful context for a close analysis. Data can also draw attention to unexpected patterns not immediately visible in the material, and it can confirm or challenge hypotheses arising from close readings of artworks or other sources. For example, we might ask whether women artists depicted plants differently from their male counterparts, or examine, confirm or nuance relationships between class and plant choice, or between plants and gender, as discussed in this article.

State of the Art: Plant-centric readings of nineteenth-century art

Houseplants in nineteenth-century Danish art have not previously been the subject of a comprehensive, systematic study. Perhaps this is due to the unassuming nature of their role in the artworks: they generally appear as modest everyday elements that attract little attention. The figures in the paintings often have their backs turned on the plants or gaze past them, and the plants recede into the background as secondary, though often richly coded, elements [cf. figs. 1–4]. Generally speaking, the various details found in nineteenth-century interior paintings are laden with meaning, including the plants.13 Flowers, moreover, were richly associated with symbolic connotations, and in the nineteenth century an actual language of flowers, or floriography, with codified messages became fashionable.14 In addition to this, art is always ‘conditioned by the culture and worldview [of the historical period] in which the image was created,’ as Eva de la Fuente Pedersen and Hanne Kolind Poulsen note in their introduction to the exhibition catalogue Flowers and World Views (2013). Those aspects, culture and worldview, are also reflected in art’s depictions of plants.15 Indeed, several individual analyses of houseplants in Danish art examine their references to conventional symbolism beyond the work itself; their role in creating meaningful relationships between pictorial elements within a work; or the ways in which plant depictions reflect the period’s culture.16 A good example is the many analyses of Martinus Christian Wesseltoft Rørbye’s View from the Artist’s Window, painted between 1823 and 1827 [Fig. 6].17

Art historian Dyveke Helsted describes Rørbye’s painting of the view from his childhood room at Amaliegade 45 in central Copenhagen, with houseplants on the windowsill in the foreground and, in the distance, the view of the naval base at Nyholm with the fleet’s berth and a masting house crane.18 Art historian Kasper Monrad emphasises how the windowsill and the open window act as a symbolic threshold between inside and outside: the home, with its plants, represents the familiar and safe, while the harbour serves as a window opening up on faraway worlds.19 Building on art historian Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark’s earlier analysis, Monrad interprets the row of plants as an allegory of ‘a young person’s life from birth until they stand on the threshold of leaving home and beginning adult life.’20 The cutting symbolises the child, thriving in the safe environment of the home; the plant with round, pink flowers is a globe amaranth, also known as bachelor’s button in both Danish and English, a name pointing to burgeoning youth; and the flowering hydrangea at the far right symbolises the young person in full bloom, ready to step out into life through the open window.21 Monrad posits the work within the broader context of Denmark in the 1820s, a time marked by economic decline and the loss of Norway in 1814. He argues that the painting reflects a yearning to venture out, but also ‘the limited outlook that most Danes of the time shared, confined to their immediate surroundings, yet perhaps casting a cautious, stolen glance towards the wider world.’22 In Monrad’s reading, the houseplants serve simultaneously as an allegory of human development and as an image of Denmark’s somewhat constrained horizons in this period.

The Danish ethnographer Lene Floris points to another abundance of meaning in Rørbye’s work. She interprets the painting as a testimony to a burgeoning fashion in 1820s Denmark: the houseplant. For Floris, Rørbye’s painting illustrates the arrival of houseplants in bourgeois homes at the end of the eighteenth century and their increasing spread throughout the nineteenth century.23 The title of Floris’ article reflects nineteenth-century usage, which described the keeping of plants indoors as ’the garden on the windowsill.’24 Her article points to nineteenth-century paintings as an overlooked source for insight into a neglected field: the cultural history of Danish potted plants and the many narratives attached to them:

Potted plants can tell many stories. They tell of human relationships with nature when nature is moved indoors and placed behind glass. They tell of home décor and fashion, and of women’s tasks and gender roles as they changed over time.25

Since Floris wrote her article in 1999, global environmental crises have become an unavoidable context for us all, one that not only foregrounds environmental decline as a pressing theme; it also challenges the nature–culture dichotomy that shapes our view of plants. Anthropologist Natasha Myers suggests that we take a closer look at how specific sites, especially gardens, invite particular relations between humans and plants:26

Gardens are for me poignant sites for anthropological inquiry into the various ways that people stage relations with plants – whether these relations are intimate, extractive, violent, or instrumentalising.27

We propose that nineteenth-century depictions of ‘the garden on the windowsill’ can be read as stagings of the intimate and entangled relations with plants highlighted by Myers’ concept of the planthroposcene. In art, we can trace the plant-related cultural-historical perspectives Floris mentions as well as the global dimensions that have become so insistently urgent today. Our interest, however, is not confined to viewing the works as sources of knowledge about houseplants as part of Danish cultural heritage. We also consider how art performatively helps to establish the space of meaning that conditions our perception of plants through the layers of significance embedded in the works. In other words, individual works reveal how categories relating to nature – but also to gender, class, nationality and so forth – are performatively created and negotiated through the aesthetic staging of plants within the domestic sphere. The following analyses provide concrete examples.

This project thus situates itself within a wider wave of re-readings of historical art, where the thesis of the (pl)anthroposcene offers up new perspectives on older works. Paintings of city life by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) and Claude Monet (1840–1926) are now read as evidence of fossil fuel combustion and as signs of the dawn of the Anthropocene epoch.28 In similar ways, nineteenth-century landscape paintings are being reinterpreted in relation to broader knowledge formations concerning, for example, colonialism, animal husbandry or cultural conceptions of nature.29 Moreover, the expanding field known as plant humanities introduces analyses that give topical relevance to natural, cultural and art-historical archives and collections, as exemplified by the extensive work of art historians Giovanni Aloi and Prudence Gibson.30 Finally, our project continues the work done by a series of Danish exhibitions with substantial research-based catalogues that have explored our complex relationship with plants through new readings of historical art. In particular, we draw on our earlier experience with ARoS’ The Garden: End of Times; Beginning of Times (2017) and the Faaborg Museum and the Hirschsprung Collection’s Jordforbindelser / Down to Earth (2018).31 Other examples, including Flora at Stavanger and Randers Art Museums (2019) and Flowers in Art at ARKEN (2021), have also helped establish the theme in a Danish context. Drawing on critical positions such as new materialism, feminism, and postcolonial and decolonial theory, this particular field of study and curating sees visual art as part of a broader visual culture that has contributed to naturalising problematic ways of seeing. It has been pointed out, for instance, how art aestheticizes Anthropocene environmental disruptions in ways that make people grow accustomed to them – and thus overlook them. As professor of visual culture Nicholas Mirzoeff concludes: ‘The Anthropocene is so built into our senses that it determines our perceptions, hence it is aesthetic.’32 Thus, historical art holds potential for nurturing alternative narratives if we choose to approach it differently.33 Our central idea is precisely that nineteenth-century art can play a part in the broader effort to find better words, narratives and images for what we once called ‘nature’ – for the planet, the biosphere, or our life with other species – an endeavour currently much in demand across the Environmental Humanities.34

In our project, these analytical approaches are supplemented by a quantitative method building on distant reading methods that have become increasingly widespread in recent decades. In Danish art history, for example, Gertrud Oelsner has employed a form of distant reading in her work on nineteenth-century Danish landscape painting, based on a systematically compiled group of works.35 Multivariate statistics are not yet widespread in art-historical studies, but they will undoubtedly gain momentum with the rise of generative AI and the general development of digital art history as a field.36

Seeing art through the lens of botany and horticulture

Despite the complex theoretical framework, our project is guided by a simple method: we focus on the plants. They govern our selection of works and our analyses. In close readings, we look beyond the narrow categorisation of plants as ‘houseplants’ and instead regard them as botanical specimens in their own right, with their own histories of cultivation and breeding. This raises questions about which plants we are looking at, where they originated, how they came to be on the windowsill, how they were cared for and by whom – as well as how they were perceived by the artist. We thus adopt an interdisciplinary approach to the works where botanical, ethnobotanical, and cultural-historical expertise informs our analyses. This perspective enables us to uncover broader narratives within the works; narratives about the entanglements of human and plant life.

Rørbye’s painting is particularly interesting because it is one of the earliest identified examples of Danish art featuring houseplants. It forms part of the starting point for the development we trace throughout the century, making the houseplant a recurring motif in art [cf. Fig. 5]. Houseplants were a relatively new phenomenon in the bourgeois home at the time, inviting readings that consider the historical context.

The history of Danish houseplants is part of a larger history of global plant migrations, which gathered momentum in the seventeenth century when human activity fundamentally altered the distribution of plants.37 Over the course of two centuries, more than 5,000 plant species were moved across continents, given new scientific names, and made part of new cultural and scientific contexts.38 Bulbs such as hyacinths and tulips constituted a growing market, and the activities of European explorers and the expanding colonisation of the tropics meant that an increasing number of tropical and subtropical plants made their way to Europe. These were initially cultivated in royal and aristocratic gardens, and later also in botanical gardens. From the late eighteenth century, and especially throughout the nineteenth century, houseplants found their way first into bourgeois homes and subsequently into those of the wider population.39

The history of houseplants has been addressed quite extensively in literature outside of Denmark,40 while the field is rather more sparingly described in a Danish context.41 Even so, primary sources still offer some insight into the spread of houseplants in the 1820s, when Rørbye painted his work. The gardener and horticultural writer Julius August Bentzien (1815–1882) noted in 1858 that twenty years earlier, in the 1830s, houseplants in windows were not a common sight: ‘Back then one could walk through several streets without seeing flowerpots in any window,’ he wrote.42 Indeed, not until 1833 did an actual flower market open in Copenhagen: it did so at Holmens Kanal, where commercial gardeners could sell their potted plants directly to the townspeople.43 Prior to this, the citizens of Copenhagen had access to ornamental plants via sales from the Botanical Garden at Charlottenborg, from commercial gardeners, or by ordering from catalogues provided by suppliers abroad. In the 1820s, however, such botanical abundance must have been an unusual sight and a status symbol evoking the floral splendour of distant lands.44

If we regard the plants as botanical specimens in their own right and ask about their countries of origin, a surprising pattern emerges: on the left-hand side of the window ledge we see a Hydrangea macrophylla, native to Japan; in the centre is an Aloe vera, native to Oman on the Arabian Peninsula; and to the right, just before the cutting, a Gomphrena globosa (globe amaranth or bachelor’s button), native to Mexico, Central America, and tropical South America.45 The plants in the painting thus hail from different corners of the globe and have come together on a Danish windowsill in the northern hemisphere. Taken as a whole, the windowsill represents all four quarters of the world.

We do not know whether Rørbye deliberately arranged the plants to represent the four corners of the world. It is not, however, unlikely. At the time, there was widespread interest in science and botany, especially in the plant geography founded by Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) in the early nineteenth century.46 In 1822, the Danish botanist and later director of the Botanical Garden, Joachim Frederik Schouw (1789–1852), published a Danish plant geography strongly inspired by Humboldt.47 It was also during this period that volumes of the extensive Flora Danica (1761–1883) were being published on the basis of expeditions across the Danish realm, meaning that the plants described were embedded within a specific geographical context.48 When Bentzien published one of the first Danish handbooks on the care of houseplants in 1851, he likewise included information about the plants’ geographical origins – and in some cases also about their journey to Europe. He describes, for example, how the botanist Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820) brought the hydrangea to Kew Gardens in London from Japan in 1790, and notes that before its introduction in real life the plant was already known to Europeans from Chinese wallpapers.49 Regardless of Rørbye’s intention, this work represents not only the ‘garden on the windowsill’, but also the wider world given that a global perspective is present in the painting through its plants.

At the same time, the work also demonstrates an interest in plants collected and placed behind glass in human-made and human-controlled growing environments. The small glass cloche with a cutting underneath it points to a knowledge of plant propagation, including an awareness that tropical and subtropical plants required special conditions in order to thrive. The birdcage, moreover, reflects the wider fascination with exotic ‘curiosities’ or naturalia in which the interest in plants was often embroiled.50 It is therefore natural to view the plants not only as houseplants representing the domestic and the Danish spheres in a narrow sense, but also as specimens exemplifying the wider natural world from which they were drawn.

The painting is structured by repeated grid patterns: note the gauze curtain whose tassels are doubled in the mirror, the small railing in front of the window echoed in its cast shadow, as well as the birdcage and the ship’s masts in the background. The accumulated effect creates a kaleidoscopic feel that does not, as earlier analyses suggest, establish an opposition between indoors and outdoors, the interior and exterior world, but rather seems to mirror them in each other. Within these myriad reflections, the painting revolves around the technologies that enabled foreign life forms to thrive within the Danish home.51 These include the specific growth environments – clay pots, birdcage, glass cloche, and the windowsill protected by panes of glass and the small railing – and the ships themselves. After all, the ships were the technology that enabled the large-scale transfers of plants from distant lands to Europe, and seafaring later became central to the trade in plants.

Earlier descriptions of the harbour area depicted in the artwork have focused primarily on the view of the naval dockyard with its warships.52 Yet the middle ground is also of interest: it shows the Copenhagen harbour front, which at the time was heaving with merchant vessels that, among other things, brought ornamental plants, flower bulbs and seeds into the city.53 In the painting, a smaller merchant ship – probably a two-topsail schooner – is moored at the quay behind an anchor and a row of barrels or bundles that may well be cargo.54 The trading companies that transported plant matter such as coffee, sugar and tea to Denmark via long-distance shipping were also located in this area. The West India Warehouse on Toldbodgade, visible in Rørbye’s view of a Weighing Station at the West India Warehouse from 1826, is just to the right of the vista framed by the window.55 Viewing the harbour as a transitional zone pointing out towards faraway, foreign places, as Monrad describes in his analysis of the work, is an obvious interpretation. In our analysis, however, we wish to emphasise that the foreign was not only something one sailed out to encounter, but also something that arrived in Denmark due to the activities of trade and science.

Houseplants as an emerging cultural and aesthetic category

This analysis opens up new horizons of meaning in Rørbye’s painting. The plants represent not only the domestic sphere, but also the wider world which entered Europe in the service of science and global trade as part of an imperial and colonial culture. The dynamic movement of the work thus flows not only outward through the open window, but also inward through it. The windowsill emerges as a zone of domestication for plants from other parts of the world, making it a liminal space or contact zone between inside and outside, home and abroad, north and south, where the distant becomes visible within the familiar and the everyday.

According to the French historian of science Bruno Latour, modernity is characterised by a constant production of hybrid nature–culture phenomena.56 The period from the Enlightenment onwards is generally held to be marked by the differentiation of social and epistemological spheres, where nature begins to be understood as something fundamentally separate from society or culture. Latour argues that such a separation never actually took place, a fact proven by the hybrids themselves. The houseplants in Rørbye’s painting appear precisely as such nature–culture hybrids. They are biological organisms that, by virtue of their specific biology, reflect the ecosystems and climates from which they originate. Yet at the same time they have been collected, transplanted, propagated and adapted to Danish homes through specific technological practices.57

The Anthropocene, as Mirzoeff explains, is an aesthetic category, and visual art has taught us to appreciate (and thereby to overlook) Anthropocene transformations. Landscape paintings have aestheticized the monocultures of agriculture and forestry, teaching us to regard them as ‘beautiful’ and as ‘Danish’ nature.58 Similarly, one might argue that the many interior paintings of the nineteenth century featuring houseplants contributed to a gradual shift in the perception of plants from distant regions, making observers see them as Danish and as a natural part of a Danish home. Viewed in this light, Rørbye’s painting not only reflects a cultural tendency, but also actively produces it through the aesthetic staging of plants as part of a bourgeois Danish interior.

Rørbye’s work thus marks the beginning of a visual process of domestication in art that continues throughout the nineteenth century, one in which plants were gradually integrated into a Danish cultural repertoire as they were visually inscribed into bourgeois, and later also rural, homes [Fig. 5]. This development took place concurrently with the practical domestication, commercialisation and often hybridisation of plants by commercial gardeners and florists, as well as with their literary representation in both fiction and the increasingly popular handbooks on houseplant care from the latter half of the century.59 By representing the plants within the framework of a home, the artworks also link them to the social categories associated with the domestic sphere. Class, gender, and national identity – and, with them, Europe’s colonial past – emerge as key perspectives, which we will explore further in the following analyses.

Houseplants and class

The plants in Rørbye’s window ledge reflect his family’s economic means.60 Bentzien, in his 1858 text, specifically describes Rørbye’s street, Amaliegade, and clearly regards houseplants as a fashion phenomenon linked to class: ‘There are plants not fashionable enough to be welcome in the homes of the wealthy and distinguished,’ he writes.61 At the same time, he celebrates the fact that the phenomenon of houseplants had spread across all social classes. Economic resources governed which types of plants were attainable to individuals, just as they did for other consumer goods.62 The pelargonium (often known as a geranium in English) is a particularly interesting example in this respect. It was the height of fashion in the Nordic countries in the first half of the nineteenth century, to such an extent that people spoke of an outright ’pelargonium mania.’63 Over the course of the nineteenth century, the plant became popular among the common people due to being easily propagated from cuttings.64 It also lent itself well to producing hybrids, giving rise to varieties with different scents, leaf sizes and flower forms. These hybrids became part of the expanding flower trade – and remain so today.65 Subsequently, however, the pelargonium lost its prestige, almost becoming a symbol of the common folk, as we see in art – for example, in many of Laurits Andersen Ring’s depictions of rural life [Fig. 8].

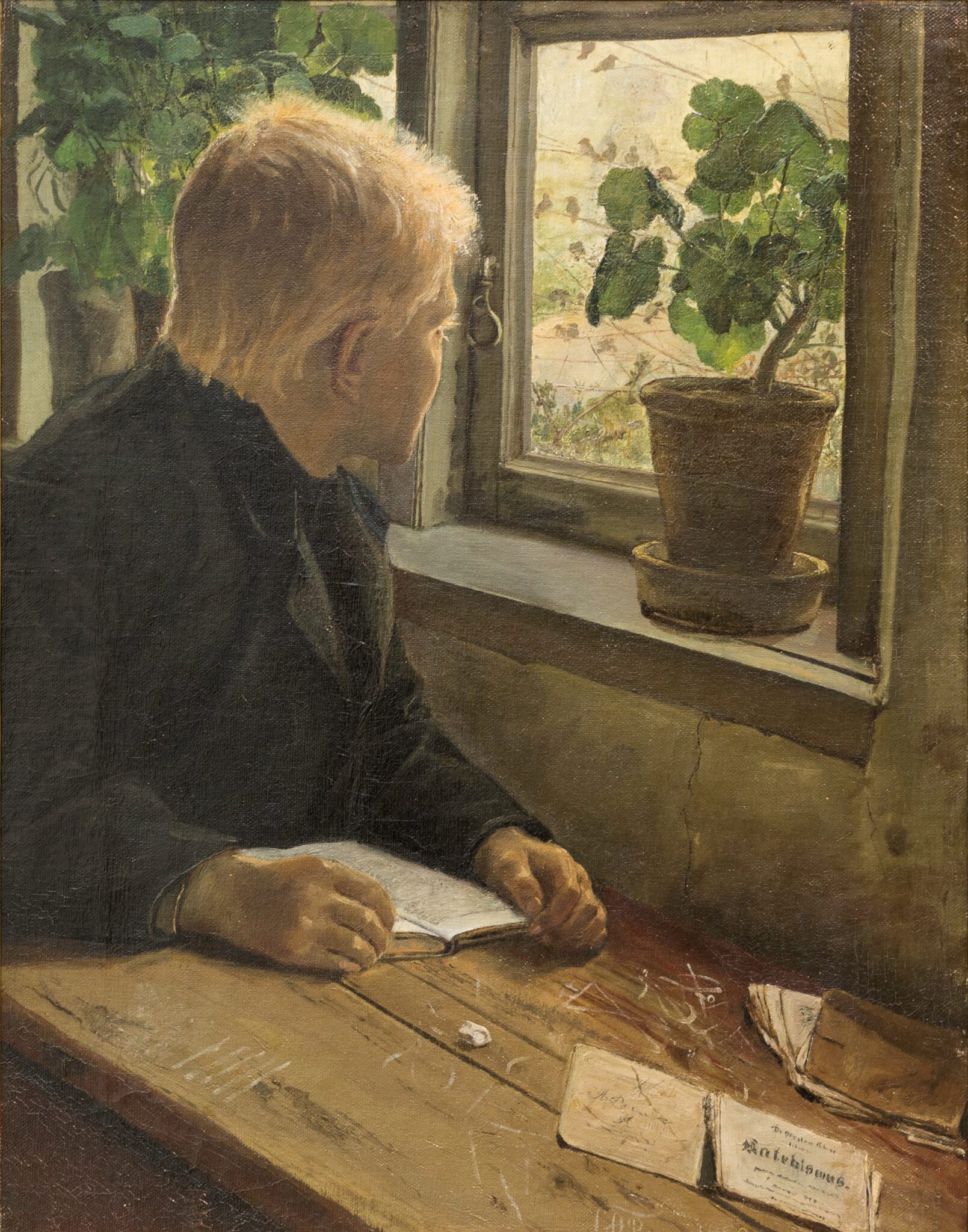

A good example is Ring’s painting A Farm Boy Doing his Homework (1883), in which two pelargoniums (Pelargonium sp.) are placed in the window [Fig. 9]. In this work, the rustic wooden table, the coarsely woven clothing, the clay-daubed and cracked walls, the pelargoniums in turned clay pots on the window ledge, and the descriptive title all serve to draw us into a peasant household of the 1880s. Here too, the windowsill serves as a boundary zone separating inside and outside. The home is presented as an educational environment: the boy has Martin Luther’s (1483–1546) Small Catechism on the table, turned so that the viewer can easily see its title page. Yet the boy, looking on the verge of jumping to his feet, seems more intent on gazing out – perhaps at the birds in the bush outside – than on his lessons.66 The pelargoniums obscure the view and appear as a cultivated form of nature, a contrast to the free nature beyond the window. Given that Ring, like many other painters, would actively stage and rearrange his subject matter, his works cannot be read as one-to-one depictions of reality.67 They do, however, offer us some impression of the way houseplants were regarded at the time.

The colonial narratives of houseplants

Like the kaleidoscopic pattern of reflections in Rørbye’s work, houseplants in nineteenth-century art seem to destabilise the scenes in which they appear because they open up a multitude of supplementary perspectives. One of the most frequently found plants in our material is the pelargonium, presenting the rich variety characteristic of the species. The pelargonium originates in South Africa. In the mid-seventeenth century, Dutch traders established a colony in the region, one which expanded during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries under both Dutch and British rule, a process involving the importation of enslaved people from other regions and the displacement or extermination of parts of the indigenous population. Dutch traders brought the first pelargonium species to Europe in the seventeenth century.68 Like many other plants collected from other parts of the world, it was given scientific names in order to be integrated into the botanical taxonomic system,69 because houseplants are not only nature–culture hybrids: they are also cultural hybrids belonging simultaneously to several cultures, each with its own perspective on, name for, and use of the plants. In South Africa, for example, the pelargonium was used both as food and as medicine.70 In this way, plants challenge the idea of a stable, unequivocal national identity from within their domestic settings, pointing instead to the complex, often invisible connections between Danish interiors and the – frequently colonised – world that supplied its green inhabitants. The windowsill thus becomes a special site for the negotiation, inscription or articulation of hybrid identities.71

At first glance, the windowsill in Ring’s work appears as an emblem of a Denmark we might look back on with nostalgia and perhaps revisit in museums such as Den Gamle By. The casement windows are typical of older Danish homes. The Small Catechism speaks of the efforts made to ensure that even peasants would learn to read and learn about Christianity in Danish. The pelargonium contributes to establishing the strong sense of Danishness in the paintings, since it was such a characteristic houseplant among the common folk in nineteenth-century culture.72 Conversely, paintings of this type helped establish the view of the plant itself as typically Danish.

Yet alongside stories of class, national identity, plant trade and plant exchanges, the pelargonium also carries Europe’s colonial history with it onto the windowsill and onto the picture plane. Ring’s work does not necessarily directly invite these supplementary perspectives, but one may choose to inject this knowledge of plants into one’s reading of the paintings, thereby seeing them as testimonies to Europe’s colonial past.

Houseplants and gender

Many other sources frame plants as part of women’s care work in the home. For example, the publication Raadgiver for Hus og Hjem (Advice on House and Home, 1885) observes that a loving and good housewife will tend her flowers as she does her children and will ‘reap rich rewards for doing so’, emphasising that this need not cost anything since cuttings are easily obtained from friends and acquaintances.74 Women were thus expected to acquire practical knowledge of plants, knowledge no longer reserved for gardeners, and their management of good taste within the home was not simply a matter of style, but also of acquiring botanical or horticultural expertise. Within the home, a mutual exchange was at play: the woman tended the plants, which in return adorned the household, conferring status and added comfort.75 In this way, plants contributed to the construction of the housewife as an ideal; a process that unfolded during the nineteenth century as the bourgeois nuclear family became the norm.

In Viggo Pedersen’s (1854–1926) depiction of an everyday scene set in a sun-drenched living room, we witness a tender encounter between the artist’s wife, Elisabeth, and their child, Christen. The mother is seated on the floor, tilting her head attentively as she listens to the child, who reaches trustingly towards his mother’s face [Fig. 11]. Illuminated by a light that carries an almost religious quality, mother and child form the central subject of the work. Six houseplants stand on the windowsill, relegated to a peripheral background role; they are even cropped so that only their pots and lower stems remain visible. Like the sewing by the window, or the clutter on the floor and on the escritoire, the plants belong to the sphere of the housewife’s duties. Positioned directly in the fall of sunlight, they filter and refract the light, and their lush, healthy foliage – together with their sheer abundance – testify, like the child himself, to the life that the mother nurtures within the domestic sphere.

Women and houseplants shared similar circumstances during this period: both were confined to the private sphere of the home. This was before women won the right to vote, and a time when married women were barred from holding business licences.76 In the nineteenth century, women were also denied entry to the art academies. They had to make do with private tuition, where flowers and interiors were among the primary subjects.77 Women artists such as Alhed Larsen (1872–1927), Anna Syberg (1870–1914), Anna Ancher (1859–1935), and Christine Swane (1876–1960) painted the very plants they themselves tended in their homes, adding new layers to the narrative of care visible in these works [Fig. 11].78 Despite the labour involved in tending plants on windowsills, in greenhouses and gardens, art historian Søren Thorlak Madsen points out that the plants in these works seem to represent a sanctuary, a space for retreating from other forms of care work.79 Perhaps this is why women artists often chose houseplants as their main subject matter? [Fig. 12]

A source of new insight and renewed relevance

The close readings presented in this article demonstrate the richness of meaning that can be found when you cut across disciplinary silos and analyse the art through multiple perspectives spanning the natural sciences and the humanities alike. For example, our analyses are supported by botanical, horticultural, ethnobotanical and cultural-historical studies and perspectives. Such analyses can reveal overlooked aspects in well-known works, especially those that concern the entanglements of human and plant life. This interdisciplinary approach can inscribe older works within a present-day perspective, allowing historical art to be considered in relation to both contemporary art and current issues – thereby honing the relevance of the collections found in Danish art museums.

A plant-centred approach to art, alternating between close and distant readings and between diachronic and synchronic perspectives, can thus provide new knowledge about – and new means of presenting and mediating – our relationship to plants. The works offer insights into the concrete entanglements of human and plant life within the domestic sphere as they unfolded throughout the nineteenth century. The genre of ‘houseplant art’ shows how plants came to play a role in social categories such as gender, class and nationality. It also illustrates how plants linked the intimate, domestic Danish sphere with global structures such as colonialism and transnational trade, thereby connecting social, cultural, botanical and economic aspects from widely different parts of the world. None of these topics have been examined extensively with Danish houseplants as a point of departure. Future studies might profitably look at broader bodies of work in this light, conducting similar analyses in order to nuance, confirm, or challenge such theses through the use of the database. Also, the database itself may generate new hypotheses requiring further close analysis.

Moreover, houseplant art can provide a framework for new forms of public engagement, offering a collective sensitivity towards plants through exhibitions and other interpretive formats. ‘Plant blindness’ is a widespread phenomenon, particularly in relation to houseplants sold purely for their aesthetic qualities – a narrow view that obscures broader understandings of them as botanical nature–culture hybrids.80

Houseplant art has the advantage of being relatable, since it depicts intimate portrayals of plants within domestic settings that are very similar to the ways we cultivate plants in our homes today. Thus, the plant motif can give otherwise abstract ideas about the entanglement of human and plant life concrete form. Audiences can gain greater knowledge and a broader aesthetic appreciation of how human and plant lives intertwine on a large, macrosociological scale and on the microsociological scale of the home, whether a peasant household in Jutland or an artist’s childhood home in central Copenhagen. The motif also quite literally brings the Anthropocene’s global questions concerning the relationship between humans and nature down to earth, grounding it in everyday, relatable perspectives as plants forge a link between the intimate sensory world of the home and wider global contexts.

Through houseplant art, museums can make distant and complex issues accessible and relatable. They can serve as forums for inclusive conversations in which visitors encounter new planthroposcene perspectives on the houseplants they see in art and on their own windowsills. The works may prompt curiosity and perhaps inspire audiences to seek knowledge about the plants they encounter, whether in paintings or at home, perhaps asking about their origins, how they ended up on the windowsill, and who tends to them. Such enrichment of the audience’s outlook on plants may counteract the apathy towards global environmental challenges that many warn against.81 This is one of the core ideas behind the exhibition Plant Fever. The World on the Windowsill, opening in September 2025 at The Hirschsprung Collection and Ordrupgaard, and in 2026 at Faaborg Museum as part of the project Hidden Plant Stories.82

Museums can use their collections to tell new stories about the evolution of our relationship to plants in the home: plants being collected, propagated, cultivated and enjoyed within the domestic sphere. Plants with which the Danish people developed an intimate relationship by tending them, sharing them with friends and family, reading about them and painting them. These may be planthroposcene stories about intimacy, but also about power relations: between humans and plants, between the Global North and South, between colonial powers and colonised regions. At a time when our future with plants is being fundamentally reconsidered, it is worth looking back at our past with plants – and at the period of transformation when the houseplant emerged as a new cultural category.