Summary

In 1948 and 1949, Richard Winther and Gunnar Aagaard Andersen, together with several other artists from the artists’ association Linien II, created a series of experimental works that transferred their artistic experiments with so-called Concrete art, which otherwise primarily found expression as painting or sculpture, into the medium of sound. The results took the form partly of ‘noise paintings’1, as Richard Winther would later call them, recorded on lacquer discs, and partly as a concert work intended for performance by classical musicians playing from a graphic score. Together, the works constitute what are probably the earliest examples of sound works by Danish visual artists and can help illuminate how sound enters the visual arts in Denmark, and how works of art created in sound both conform to and challenge art conventions and institutional logics.

Articles

Prelude

In a 1971 radio interview, Richard Winther described a pivotal encounter with artist Gunnar Aagaard Andersen at the gates of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts one day in 1948 or 1949. Winther, by his own account ‘completely over the moon’, shared with Aagaard Andersen an idea he had just conceived: the notion that the ‘Constructive’ paintings they were working on at the time would be wonderfully suited to being played on a barrel organ.1 The link between the paintings’ rhythmic series of fields and lines, evenly distributed across the picture plane, and the perforated paper strips used by barrel organs does indeed seem obvious once you have made the connection across art forms.

Initial problem statement

The artists’ association Linien II, of which Winther and Aagaard Andersen were key figures, paved the way for an inter-media return of concrete art in Denmark in the years after the Second World War. As art historian Mikkel Bogh writes in volume 9 of Ny Dansk Kunsthistorie (New Danish Art History) from 1996, this was a return where the interest was not primarily ‘directed towards materiality. On the contrary, the inclusion of the most diverse materials was justified by a gestural approach that allowed the artists to jump from one medium to the next’.2 However, one medium seems to evade Bogh’s otherwise keen gaze: sound. In what follows, I will focus on how, in the years 1948–49, several of the artists from Linien II also experimented with relocating their artistic endeavours into the medium of sound. The mischievous silliness of Winther’s barrel organ analogy in itself can be said to demonstrate the playful ease with which an artistic idea could be shuffled around between different media. The invisibility of sound in art history writing is symptomatic, and with this article I hope to contribute to inviting closer art historical scrutiny of sound in order to provide a more multifaceted picture of a Danish art scene that, then as well as now, has a soundtrack.3

By listening more closely to the works Machine Symphony No. 2 (called Maskinsymfoni no. 2 in Danish), 1948 by Richard Winther, and Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector (Danish: Koncert for fem violiner og et lysbilledapparat), 1949 by Gunnar Aagaard Andersen, the present article aims to show how the artists could make the leap from visual to sonic media and to argue why these works should be heard as part of Danish art history. Thus, the article is also the first step on the way to establishing an initial listening position couched in (visual) art history, a position which forms the starting point for my ongoing PhD project with the working title Dansk lydkunsts historier – Histories of Danish Sound Art.4

The circumstances surrounding the creation of the works

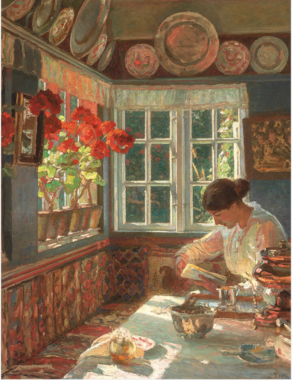

In 1948, both Richard Winther and Gunnar Aagaard Andersen were members of the artists’ association Linien II, which had loudly and proudly made its mark on the Danish art scene with something of a mixed bag of a group exhibition at the exhibition venue and bar Tokanten in 1947 [Fig. 1]. The members of Linien II posited the group as an extension of the kind of Constructivism with which the artist association Linien – hence the name – had attracted considerable attention in the years between 1934 and 1939. The affinities between the two became more evident in two exhibitions arranged at Den Frie Udstillingsbygning in 1948 and 1949, where the common mode of expression and Linien II’s artistic position were streamlined, becoming focused manifestations of Concrete art accompanied by braggingly grandiose dismissals of other artistic endeavours.5

After Winther and Aagaard Andersen’s meeting by the gates of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Winther set about constructing a sound machine that, based on converted electric doorbells, was to realise the idea of playing back the paintings as sound. However, by his own admission Aagaard Andersen grew impatient and embarked on an alternative human-machine solution: based on the imagery from a series of around fifty paintings from 1947–49, all examining the same principle of construction, he executed a series of graphic scores that he persuaded five student violinists from the Royal Danish Academy of Music to perform.6 The result was the work Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector from 1949, where the role of the slide projector was to project the graphic score onto a wall while the five violins (violinists) performed the ‘pictures’ from the score.7

The year before, as part of the preparations for the exhibition at Den Frie Udstillingsbygning due to open on 31 July 1948, Richard Winther explored another way of working with sound as a concrete material: as a sound recording cut into a lacquer disc. Winther had rented time in the privately owned music studio Wifos at Nyvej 6 in Frederiksberg, and alongside fellow artists from Linien II, Hans ‘Bamse’ Kragh-Jacobsen and Niels Macholm, he recorded two previously rehearsed pieces. One was his own Machine Symphony No. 2), while the other was Bruitist Concerto No. 1 (Danish: Bruitistisk koncert nr. 1) by Krag-Jacobsen.8 A year later, in August 1949, the same group with the addition of painter Ib Geertsen recorded another record featuring the two works Bruitist Improvisation (Danish: Bruitistisk improvisation) by Winther on one side and an untitled sound poem by Geertsen on the other. 9

It would seem that the premiere of Aagaard Andersen’s concert took place at Charlottenborg on one of the last days of August or early September 1949 as part of an all-night programme that also included performances of an opera by Henrik Buch, readings of sound poems, screenings of Winther’s experimental film, and playback of the works on the two lacquer discs. In other words, the evening presented quite a large number of works that used sound in one way or another.10 The event was also repeated on 5 and 6 September in Danish newspaper Politiken’s lecture hall.

Today, the SMK sound archive contains Richard Winther’s two original lacquer discs, deposited by Winther himself, as well as copies of the graphic scores for Gunnar Aagaard Andersen’s Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector, deposited by Aagaard Andersen’s widow Grete Aagaard Andersen. It also houses contextualising materials in in the form of notes from Winther and an interview with Grethe Aagaard Andersen conducted by artist and archive creator William Louis Sørensen.

About the SMK sound archive

The SMK sound archive was established in just one year in 1991–92 by artist William Louis Sørensen, who, at the behest of curator Elisabeth Delin Hansen, was brought in under the auspices of an employment promotion scheme with his only task being to collect this archive. The archive comprises works in the form of original media with sound and in some cases also visual components, scores and sketches supplemented with explanatory and contextualising material in the form of photo, video and audio documentation of works, performances, catalogues, articles, correspondence, and interviews conducted by Louis Sørensen with the aim of including them in the archive. A number of questions arise about the circumstances of the archive: its creation and purpose, the fact that an artist actively took part in the collecting effort, and the fact that no budget had been allocated for the collection activities.11 The main focus of the archive is clearly work with sound carried out by visual artists, but it also contains materials with a clear anchoring in other aesthetic fields – such as practices from the realms of experimental poetry, music, and theatre.

Theoretical and institutional positioning

Overall, visual art practices that use sound have found limited reception. What attention has been paid has come from two different sides: on the one hand, sound has been regarded as one medium among the many so-called ‘new media’ that began to receive serious institutional attention internationally and in Denmark during the 1980s and 1990s. The fact that SMK set up a film archive in 1990–91 and a sound archive in 1991–92 should in itself be considered an example of the institutional attention to new media, as should the founding of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Roskilde, which had new media, including sound, as a special area of responsibility. From another partially overlapping area, certain artistic practices, especially since the end of the 1990s and 2000s, have been the subject of inter-disciplinary comparisons and links with other sound practices, such as experimental music practices, as part of the establishment of so-called sound art as a concept and an independent field.12 The discourse surrounding so-called sound art has mainly taken place in the context of the relatively new interdisciplinary academic field ‘Sound Studies’ and should still be considered a work in progress, as there has never been any consensus on what the concept of sound art covers or how the field is defined.13

The historiography of and theorising about so-called sound art has often had an idiosyncratic focus on what Brian Kane has critically called the onto-aesthetics of sound art: works that, cutting across genres of music and art, can be said to address the material, ontological, and phenomenological aspects of sound and listening.14 In addition to Kane, figures such as Marie Thompson, Gustavus Stadler, Dylan Robinson, and to some extent Seth Kim-Cohen have raised criticism of the onto-aesthetic focus and its inherent problems.15 It is beyond the focus and scope of this article to provide an in-depth account of the problems associated with the theorising and historicising of so-called sound art, but to simplify matters greatly, the dominant interdisciplinary, material onto-aesthetic focus feels narrow and has resulted in a delimitation of the field for so-called sound art which does not match the many different ways sound has been – and still is – used by visual artists.

In connection with the release of the LP Linien II 1948–49, which collected the four works from the lacquer discs and the later recording of the Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector, a public discussion arose that seems symptomatic of some of the problems associated with the interdisciplinary discourse around so-called sound art. With the article ‘Linien II’s lydeksperimenter er musik’ (Linien II’s sound experiments are music), professor of musicology Michael Fjeldsøe raised a discussion about whether the works belonged to the field of music history. I responded with the article ‘Nej, Linien II’s lydeksperimenter er billedkunst!’ (No, Linien II’s sound experiments are visual art!), in which I argued that to consider the works in a music-historical context rather than an art-historical one would be missing out on something central.16 The present article pursues the argument that being aware of the works’ institutional affiliation with an art-historical tradition causes some central aspects of the works to come to the fore. First and foremost of these is how they seek to expand and challenge the conventions of visual art. These are aspects that you risk overlooking if you apply a close material focus on the sound and the properties of sound, which might perhaps otherwise be regarded as an obvious part of the wider discourse around the so-called sound art or, as Fjeldsøe suggests, if one reads them within the scope and tradition of the history of music.

In terms of theory and method, the present article thus takes its position within an institutional understanding of the art field, applying it as a central lens for how, ever since the advent of the historical avant-garde – meaning for more than 100 years now – artists have included non-traditional materials and media in a continued probing and expansion of what the category of art can include. In The Theory of the Avant-Garde from 1974, Peter Bürger’s basic thesis is that ‘with the historical avant-garde movements, the social subsystem that is art enters the stage of self-criticism.’17 The avant-garde’s attack on the art institution failed, according to Bürger, but ‘the attack did make art recognisable as an institution.’18 The conglomerate of the art institution’s various conditional parts, which Bürger calls a social sub-system, Arthur Danto summarised ten years earlier with the collective term ‘artworld’. Danto applies the institutionalist perspective that ‘to see something as art requires something the eye cannot decry – an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld.’19

This theoretical perspective allows what could be termed the social horizon of the works to come into view and showcases how they are situated in the practices of Winther and Aagaard Andersen, who build, in a highly well-informed and self-aware manner, directly on visual artistic practices and groupings found within the modernist and avant-garde movements. Thus, this theoretical lens was chosen to hone the reader’s feel for how the works speak into the contemporary art discourse as an institutional field.20

In other words, the theoretical point of view gives rise to a series of questions of a methodological nature. How did the works connect with a public? How do the works relate to other works within the given artist’s practice? How do the works and practices position themselves in relation to the surrounding art scene? It calls for a nuanced look at how these works depend on more than just what the eye sees / the ear can hear, specifically a look at the central affiliation with the art institution on which the avant-garde revolt against the very same art institution is conditioned. This applies no less – indeed perhaps to an even greater extent – when the subject under scrutiny is works in non-traditional media. The works’ use of non-traditional media should not disqualify them as part of the art world, causing them to be seen solely as part of another social sub-system – that, with Danto in mind, might be designated the musicworld. On the contrary, I hope to demonstrate that the very use of non-traditional media is part of how the works challenge the art institution. In what follows, I will refer to this institutional affiliation as the works’ filiation. The concept is borrowed from Roland Barthes, who understood by filiation the connection that a text must perform in order to be recognised as belonging to a genre. The concept of filiation seems useful in this context as it allows these works’ central challenges to the conventions of the art institution to stand out clearly, including as regards their use of non-traditional media.21

Extended problem statement

The two lacquer discs in the SMK sound archive were recently digitised alongside the copies in the Museum Jorn collection, meaning that the works can now be heard in a quality sufficient to allow a number of central principles of construction to emerge.22 This also reveals the formal devices through which the works translate the concrete artistic working methods into an artistic work with sound.23

In what follows, I will combine the outlined institutional perspective on the circumstances and positioning of the works with a close analysis of Winther’s Machine Symphony No. 2 and Aagaard Andersen’s Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector. The purpose is to show how the construction of these works makes visible a close filiation with the artists’ other practices as integrated and important parts of these. I also hope to illustrate that the sound works’ break with conventions of visual art, which at first glance could appear not just to be a leap in media, but a leap into a different type of art, music, may equally well be seen as an expansion: a classical avant-garde transgression of the conventional framework of art with a view to renewing and expanding the scope of art’s possibilities – not, emphatically, a complete break with artistic discourse and tradition. On the contrary, the leap in material is made on the basis of a keen awareness of art history and tradition, to which the artists deliberately and confidently seek to attach themselves. They extend a line in sound, as it were, resulting in works of a conceptual nature that challenge visual artistic conventions to such an extent that we should certainly not ignore them in an art historical context: rather, we should listen attentively.

Machine Symphony no. 2: A description

I am listening to a digital audio file described as ‘DEP710_13_31_12 inch record side 1.wav’, a digital transfer of a 12-inch lacquer disc recorded in a sound studio in Frederiksberg in 1948. The disc contains a recording by artist Richard Winther, who, with help from Hans ‘Bamse’ Kragh-Jacobsen and Niels Macholm, recorded Machine Symphony No. 2. The digitisation was carried out in 2021 by sound engineer Claus Byrith. I am listening with headphones at my desk for the purpose of describing the audio for this article.

The audio file opens with hissing scraping sounds, which I know are artefacts from the lacquer disc and from the equipment used for playback and digitising. It is noise generated by the medium and technology, not an intended part of the work; while it is quite dominant in the soundscape, this is not what your listening should focus on. After a few seconds, the piece begins with a piano being played, a small run of a few notes: g, g#, a, a# played with one hand and a deeper g an octave or two below, played with the other hand. After the rapid run across these notes, they are all struck together as a single dissonant chord and repeated – hammered – at a relentless pace for about half a minute. At 29 seconds, a man’s voice is heard loudly saying ‘Half a minute’ in the studio. The reverberation of the voice conveys a sense of the space in which the recording takes place: it sounds like a relatively small room, and one that is not particularly well controlled acoustically. The time signature offered by the voice produces a marked shift: the relentless piano stops and is replaced by what sounds like a horn of some sort. My association is one of those cheap plastic trumpets you use at New Year’s. The horn blower holds the crackling notes for a good 10 seconds. By the way the sound starts to tremble, I sense the effort involved in holding the tone for that long. When the horn stops, it is replaced by a distinct noise. While difficult to describe exactly, it seems familiar: like an old-fashioned TV set between channels, like white noise. I know from Richard Winther’s diary notes that the sound is in fact that of Niels Macholm rubbing two pieces of sandpaper against each other. The noise is monotonous, forming a coherent mass, but in the small shifts of the sound I sense the movements of hands. The voice shouts out ‘One minute’, the sandpaper noise stops, and the piano starts again with the same little run of the same notes, which are then once again hammered into an extended sequence as before. After half a minute, the voice again cries out ‘half a minute’, but this time the piano continues unabated. As the seconds pass, I think I can hear how the muscles in Kragh-Jacobsen’s arm tighten and how he struggles to keep the strokes even at this rapid, machine-like pace. Only when the voice once again shouts ‘One minute’ does the piano stop and the sandpaper take over. While the sandpaper is heard, a quieter voice can also be made out in the background. I recognise it from a later radio broadcast as that of Richard Winther. The sandpaper is then replaced by a new sound: an electric buzz, and Winther is once again heard in the background. In a low voice he says ‘30 seconds’ and then repeats it as if addressed to the person calling out the time markers, who shortly after says ‘30 seconds’ in an authoritative voice. The buzzer stops, the piano is back again.

The rest, just under half, of the recording is made up of blocks of the same sound materials: the piano, the horn, the sandpaper, the buzzer, and the time markers. Towards the end, the blocks of sound also begin to overlap so that sandpaper and buzzers are heard at the same time. Then the piano and horn, piano and sandpaper, sandpaper and horn. The recording ends with the piano slowing down and making a final run across the four notes, letting them subside together with a short hum from the buzzer, a hiss from the sandpaper, and with a final honking from the horn, the recording from 1948 and the digitisation from 2021 come to an end.

Analysis of Machine Symphony No. 2

The technical equipment is the most central condition governing the form of Machine Symphony No. 2. The technical recording equipment at the Wifos studio established the concrete formal framework for the work. Specifically, this meant that the sound recording had to take place within the physical space of the sound studio, and that the duration accommodated by a lacquer disc dictated the extent of the work: a 4-minute duration in the frequency range between approx. 50 Hz and approx. 10,000 Hz was what the studio’s technical equipment could record.24

The recordings took place as onetakes cut into the glossy lacquer surface of the disc while the artists performed in the studio. The resulting record could then be copied by playing it on a regular record player and cutting the audio signal from that onto a new blank disc.25 This, together with Winther’s account of the proceedings in a radio programme produced by composer Ole Buck for DR in 1971, draws a vivid picture of the recordings:

Then we made – Bamse, you know, Kragh-Jacobsens, he was a musician at Tokanten, and he painted too, and we exhibited together in 1947, right and then I tried something with … erm – I mean, I know nothing of music, and I didn’t at that time either, but I had the opportunity to play the piano, and I bashed it around in the worst way possible and saw something … that it looked like machines, right (laughs), and then I explained it, and then I talked to Bamse, right? There were a couple of us there: Bamse and Macholm and Gertsen; this whole gang, right, and then I said: “We need to record some of it”, right? And back then you didn’t have tape recorders, we had to go out to Frederiksberg, to some side road, uh, I can’t remember, Nyvej or something like that. Someone had a music studio there, so you could have it recorded there. And then we played … I played some of what I’d been practicing, and then Bamse played a piece, and then we made a piece together, because I had been to Duzaine Hansen’s to buy a corset spring and I’d brought my bike inside, and then we played that thing, stuck it in the wheel, right? And we had sandpaper and some kind of foghorn and had bought ten kroner’s worth of fireworks, and then we did some recordings.

Richard Winther’s tone in the interview strikes a light-hearted and playful note, hinting at the nature of the atmosphere surrounding the production of the works. An atmosphere that can also be felt in the works. From Winther’s diary entries and the notes attached to the records in the SMK sound archives, we know a number of details about the recordings and the sources of sound used.27 It seems that the two recordings, which took place a year apart, are condensed into a single story in Winther’s retelling in the radio interview. Combining his account with the works and his diary notes, it appears that the bicycle bell, the corset spring and the fireworks were part of the recording of Winther’s work Bruitistic Improvisation in 1949.28 In 1948, the instrumentation on Kragh-Jacobsen’s Bruitistic Concerto No. 1 consisted of the piano, played by Krag-Jacobsen himself, a test record otherwise reserved for the sound engineer’s calibration of equipment, and an electric buzzer played or activated by Winther. On Winther’s Machine Symphony no. 2 Krag-Jacobsen plays the piano, Macholm plays sandpaper and Winther play the electric buzzer and horn.29

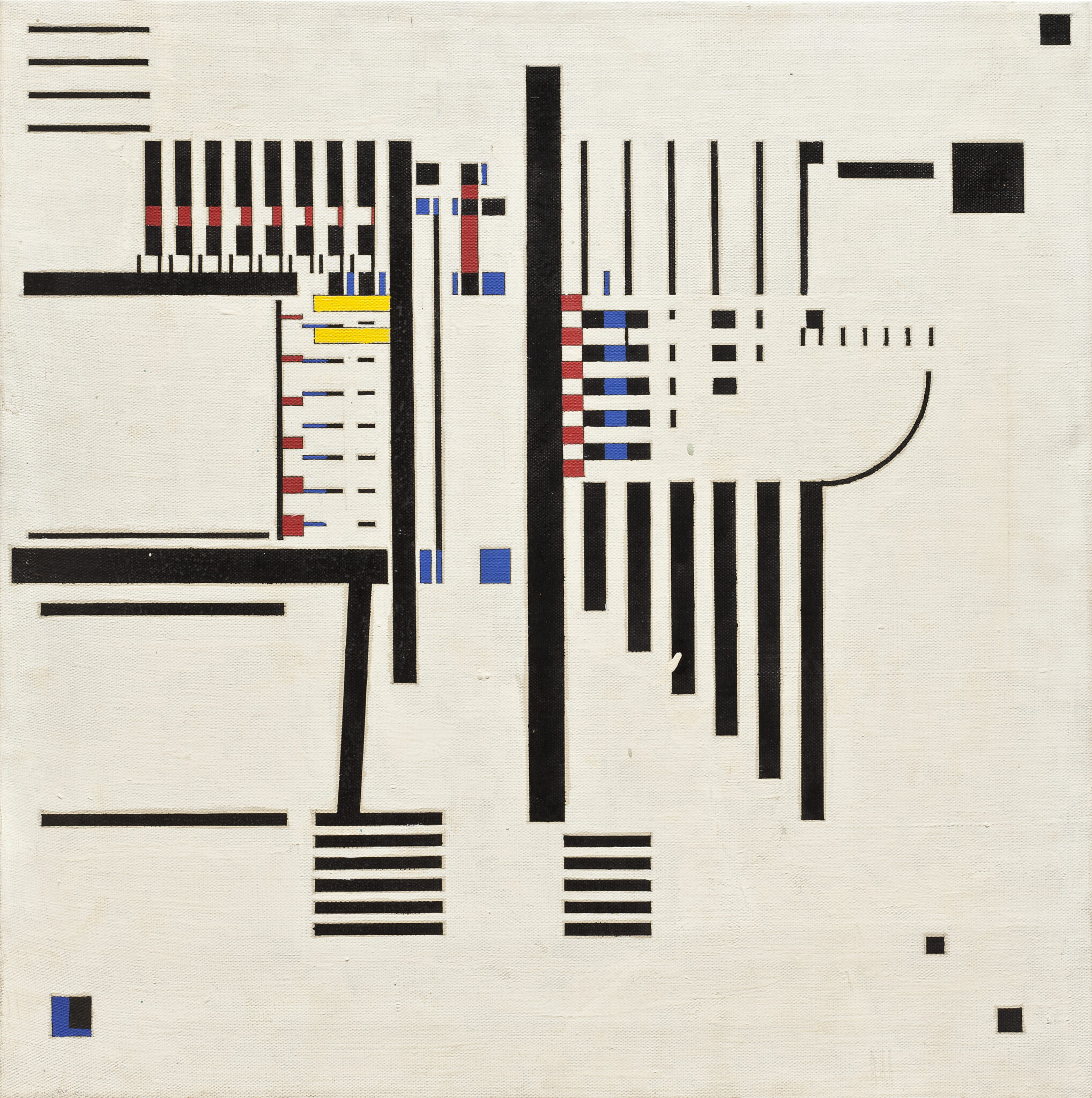

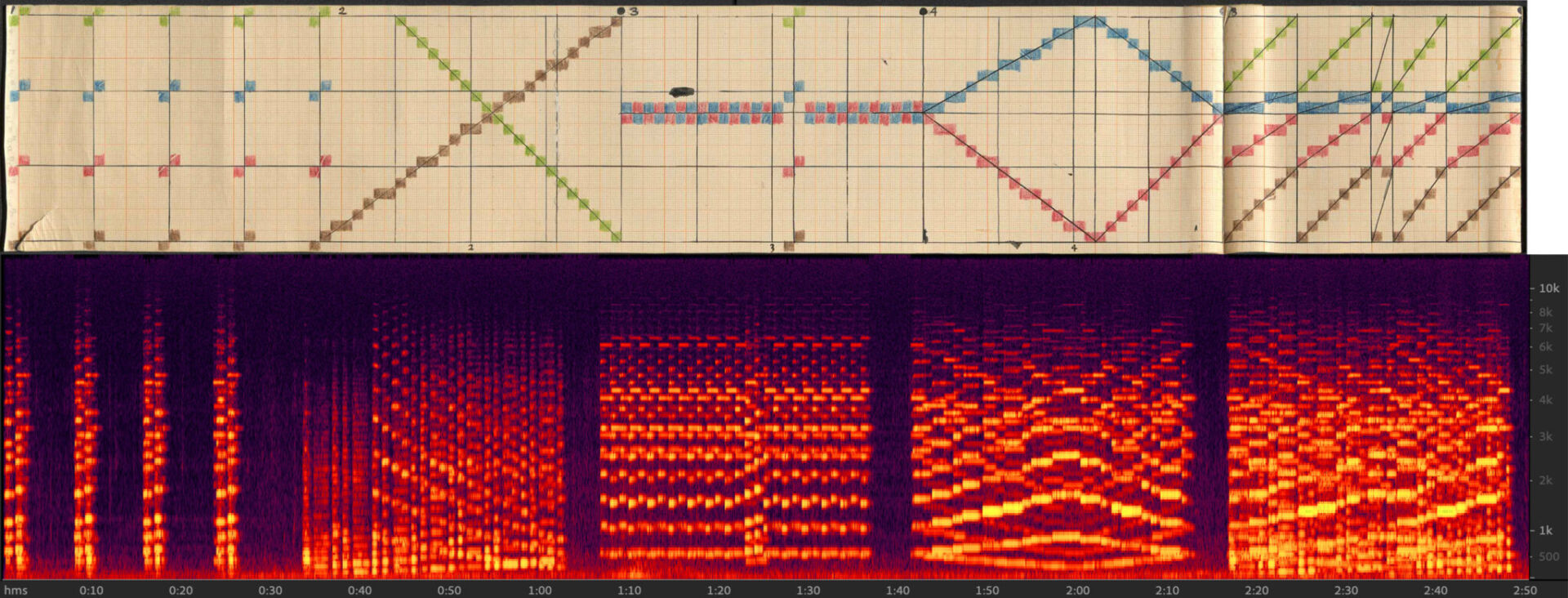

To support my analysis, I have visualised the sound in a spectral analysis that shows the frequency range from low to high and duration from left to right [Fig. 2].

In the visualisation, the work’s block-like structure is clearly evident and, in contrast to the listening experience, it establishes an overview of the work in its entirety. The listening experience and visualisation highlight different aspects of the work. Of course, there is something inherently counter-intuitive about visualising a sound work that is specifically intended as a listening experience extended in time. However, there is a central point in the fact that the visualisation, which in itself is only made possible by the digitisation of the recording, renders visible structures and proportions that show the link between the sound work and the other pieces Winther was working on at the time. Several of these, comprising paintings and sculptures alike, were shown at the same exhibition where Machine Symphony No. 2 was featured.

The voice marking time and the overall picture of the work’s block-like structure both point to the tightly controlled construction of the piece. The structure is generated on the basis of the dimensions of the medium, specifically the four-minute-long window of opportunity offered by the lacquer disc. Thus, the medium in itself is the decisive formal aspect governing the construction. The four minutes are subdivided into blocks of one minute each, which in turn are subdivided into halves, quarters and eighths and filled in by the various sound materials. In the interview with Ole Buck, Richard Winther refers to the works on the two lacquer discs as ‘noise paintings’.30 Machine Symphony No. 2’s construction and monotonous – one is tempted to say monochrome – block-like feel invites comparison to Winther’s paintings and sculptures from the same period, which also make use of monochrome fields of colour arranged in rhythmic and contrasting sequences based on and conditioned by the physicality of the work’s dimensions – their height, width, depth – such as Winther’s Constructive Concretion (Danish: Konstruktiv konkretion), 1948, where subdivisions of the dimensions of the canvas are used as a starting point for generating the series of lines and colour fields [Fig. 3].

A-hierarchically ordered plastic sound

In the article ‘The Crisis of Easel Painting’, also from 1948, Clement Greenberg turns to a concept from music, polyphony, to describe the equivalence of pictorial elements which he finds in the non-illusionist geometric ‘all-over’ painting: ‘Just as Schönberg makes every element, every sound in the composition of equal importance – different but equivalent – so the “all-over” painter renders every element and every area of the picture equivalent in accent and emphasis.’31 I believe that the equivalence, the equal importance of elements that Greenberg sees in Schönberg and the all-over painters’ equalising of different pictorial elements, also very precisely describes the use of sound materials in Machine Symphony No. 2. All of the elements generating sound – with the exception of the voice marking time – are used in a way where the sounds produced can be lengthened or shortened without causing the sound material to change its timbre or sonorous character. The sounds are made and used as a plastic material, with a monotonous/monochrome block-like feel where the sounds are adapted to the work’s time-based principle of construction. Even the piano is used, hammered, abused in the crudest way, in such a repetitive and monotonous manner that its sound becomes a single, coherent mass that can be lengthened or shortened according to the needs of the composition. The voice’s time markings dictate and reveal, in an almost didactic fashion, the sound work’s time-based construction, which delimits and defines the blocks of sound – almost like the pencil lines of an underdrawing that can still be glimpsed through the layers of paint on a painting.

A synthetic art, a new kind of painting, a space-time modulator

Experiments in form translated or reworked in artistic media other than those of traditional visual arts appear in several places in Richard Winther’s practice at about the same time, and the same holds true of Gunnar Aagaard Andersen and a number of the other artists from Linien II. As I highlighted in the introduction, referring to the words of Mikkel Bogh, the playful, almost silly sloshing around of concrete ideas between different media was rather the name of the game at this point. Winther specifically mentions in the book Den hellige Hieronymus’ Damekreds, published under the pseudonym Ricardo Da Winti in 1978, that it was a series of literary experiments, some of which are reprinted in the self-published collection of poems Den nøgenfrøede (The Gymnosperm) under the pseudonym Gro Vive from 1949 [Fig. 4], that led him to record the lacquer discs:

There is not far to go from words to sounds. In Gro Vive there are poems written by using the typewriter keys like the keys of a piano: I listened to the rhythm of the machine. I composed with sounds as if they were rectangular picture elements whose height and width were determined by tone and time, rhythm and noise, form and formlessness. (Morph, amorphous). A Bruitist concert and a machine symphony of this nature were recorded in 1948 on lacquer discs that still exist.32

![fig.3: Richard Winther: maskin-boogie, 1949 trykt i Gro Vive [Richard Winther]: Den nøgenfrøede, København 1949, s. 14.](https://www.perspectivejournal.dk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/fig3_Magnus-Kaslov_Linien-II-fri-af-laerredet-8.jpg)

Such experiments across media where poems are generated by the musical use of a typewriter, which then leads on to sound works recorded on lacquer discs, appear to be the central formal device employed in the works: the use or appropriation of the media, materials, and technologies of one art form subjected to the logic or approach of another art form gives rise to the works. This constitutes a fundamental artistic experimentation of a conceptual nature, one that strives to expand the scope of visual art and its endeavours by the inclusion of new materials and media as well as by the appropriation of material and media of other art forms. An appropriation that relates in a conceptually playful manner to the conventional forms and formats of the appropriated.

How the expansion of the visual art field that Winther undertook in the years around 1948–49 looked to him is most clearly expressed in the pamphlet liniens dokumenter (the linien documents) which was intended as the first issue of a journal that would function as a discursive forum for the art and ideas developed by Linien II.33 In a programmatic text on ‘synthetic art’, Winther articulates a number of fundamental views on the role of Constructivist art as ‘a reconstruction, a construction, everywhere in vibrant global art we see a mentality approaching that of constructivism.’34 According to Winther’s thinking, Constructive art represented the way ahead for the development of art and for a moral-ethical reconstruction that was to create a solid, universal foundation, not just for art, but for the whole of society to build on after the war.35 Regarding the use of new materials and the emergence of the new ‘synthetic art’, Winther continues:

it is not certain, moreover, that the present form of painting: canvas and pigments is the right one. [..] a new painting floats before my eyes, a multidimensional, physical-dynamic one, which can vary the means of psychic effects infinitely and simultaneously, a painting that expresses itself by direct light, both its own and light from the surroundings by means of reflective and transparent elements. […] this painting will not resemble anything that came before, it will be both film, sculpture, kinematics etc., it would therefore be incorrect to speak of ‘painting’; calling it a ‘space-time modulator’ would be better.36

The way in which Winther writes his way towards this new art, what he calls a space-time modulator, is crucial: modern techniques and materials must be incorporated in the creation of the new synthetic art. Notably, this expansion takes place via the visual arts, specifically via painting.

I propose that Machine Symphony No. 2, a work that directly experiments with media, could be regarded as an attempt to expand the realm of art and create ‘this painting’ that will not resemble anything that has come before and should therefore, according to Wither in 1948, be referred to as a ‘space-time modulator’ instead. Notably, in 1970 Winther specifically refers to the sound works from 1948–49 as ‘noise paintings’.37 In its title and in other ways, the work plays with the appropriation of terms, technologies, and (in part) instruments from the field of music, but it does so very deliberately in a self-conscious conceptual manner that gives the appropriation a tint of mischievous challenge, making it appear almost joking. To only regard/hear the work as music would be to risk overlooking its general challenge to the concept of art and the central conceptual nature of appropriation. One would, as it were, fail to get the joke, taking it at face value. I will return to the artists’ inclusion of new and non-traditional materials as well as the formats and technologies of other art forms in my concluding discussion of Winther and Aagaard Andersen’s works, but for now Ib Geertsen can have the final word. In an interview from the period, he states that: ‘There is something inherently wrong in specialising … to paint nothing but oil paintings is quite frankly old-fashioned. Modern technology makes so many aids available that the possibilities for expressing oneself are almost unlimited – just think of television, radio, film, the gramophone, and so on.’38

Concerning Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector

Gunnar Aagaard Andersen’s Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector from 1949 does not make use of recording technology. Rather, it uses a self-invented graphic form of notation to create a score to be performed in a concert situation. As is established by the title, with its metonymic humour and reference to the traditions of score music, the work is intended to be performed by five violins while the graphic score is projected onto a wall by an overhead projector so that image and sound are experienced together.

The SMK sound archive contains colour photocopies of parts of the graphic score, sheet music and an interview with Grete Aagaard Andersen conducted by William Louis Sørensen in connection with collecting the archive.39 No recordings of Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector from the performances that took place in 1949 exist, but there is a recording from 1971, when Gruppen for Alternativ Musik (The Alternative Music Group) performed the work while using alternative instrumentation. That is the recording used here as an illustration [Fig. 5].40

Description of Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector

As one of the items on the programme at the evening event held by Linien II at Charlottenborg and repeated on 5 and 6 September 1949 in the lecture hall at the offices of the Danish newspaper Politiken, audiences were treated to Gunnar Aagaard Andersen’s Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector. The audience could not see the five violinists performing the work: they were placed behind a screen, out of sight. Instead, an overhead projector provided a visual focus in the form of a graphic score, drawn on squared graph paper, which was projected onto a wall.41

When listening to the recording of Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector performed by Gruppen for Alternativ Musik in 1971, I imagine that the experience on those evenings in 1949 must have had the same rather stiff, slightly fumbling and somewhat didactic feel. However, it appears that Danish artist Jens Jørgen Thorsen, who was a student at the academy’s school of architecture at the time, had a more enraptured experience, which he describes as follows: ‘Fantastical fountains of sound gushed forth, and the sources of that fountain were shown on the wall by a slide show, like a giant painting.’42 In 1971, Gunnar Aagaard Andersen describes how ‘once a series of slides had been shown, people gradually grew able to read them. Then, you felt in the room that they knew what they were about to hear and felt a certain excitement about what was to come once translated into sound.’43

Analysis of Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector

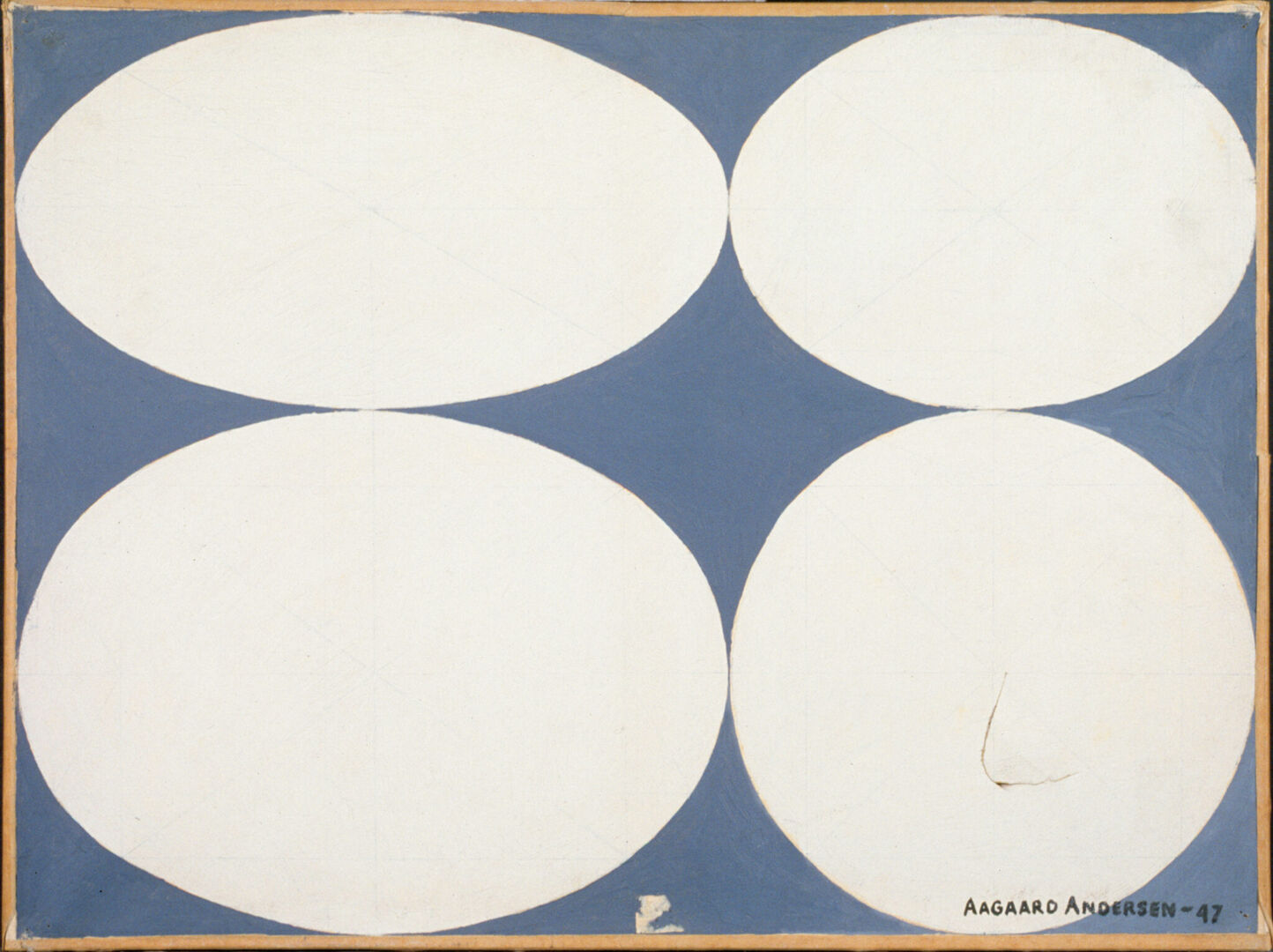

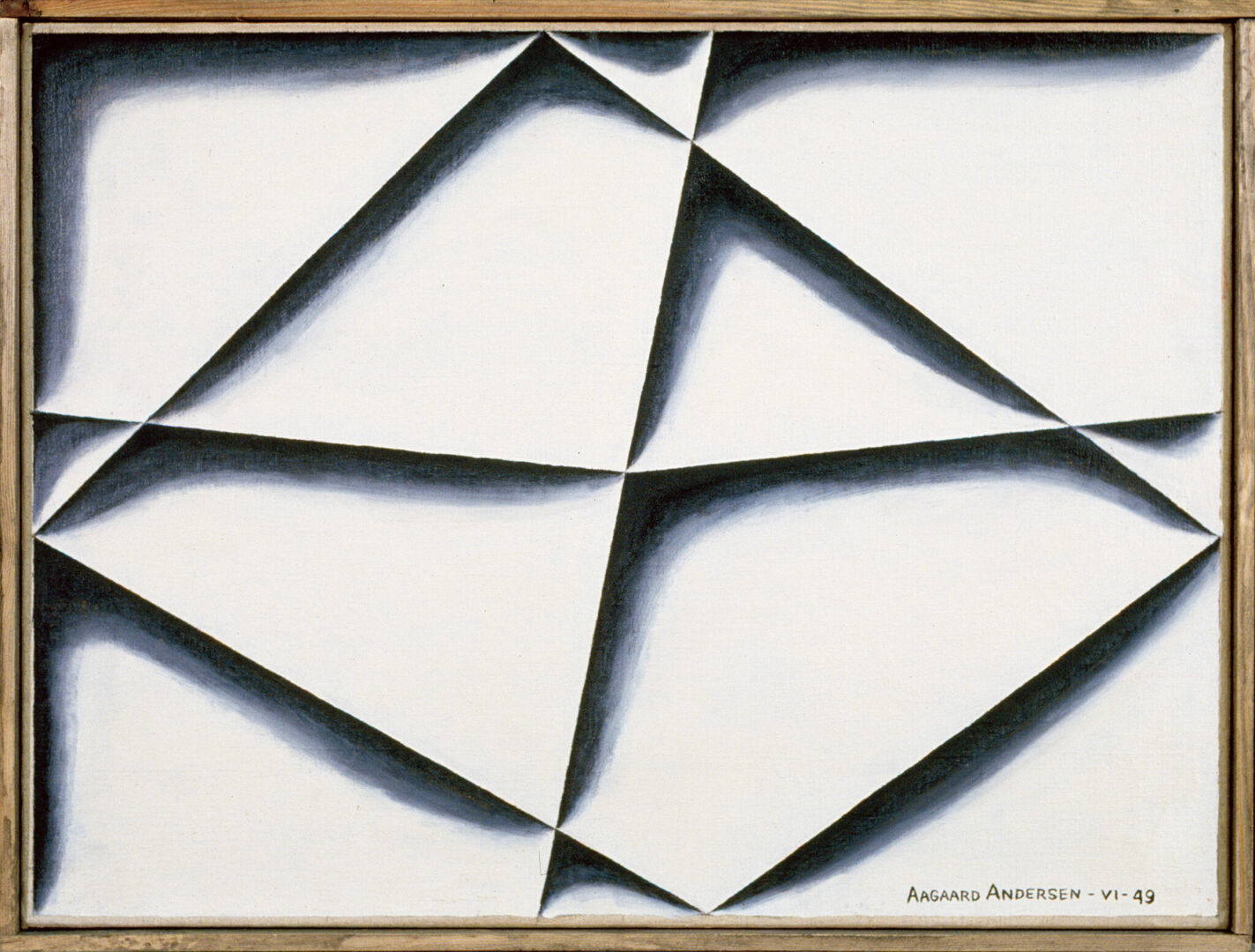

The graphic score for Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector consists of a series of numbered images, many of which can be recognised from the series of around 50 ‘forestillingsløse’ – literally ‘image-less’ – paintings that Aagaard Andersen painted between 1947 and 1949[Fig. 6] [Fig. 7].44

The entire series is constructed according to a special principle of construction that Aagaard Andersen believed to have discovered in Rubens, and which he called A division of the relationship of the sides.45 In the graphic score, the geometric imagery of the paintings is pixelated and adapted to the scores grid – literally a kind of digitisation – to match the resolution that the score uses: a grid made up of graph paper squares of 5×5 millimetres each. All the ‘pictures’ are 28 squares in length and 21 squares in height. The crucial conceptual parameters that make the pixelated drawing readable as a musical score are the facts that the 28 squares going lengthwise are intended to represent time, to be read from left to right as 28 beats, while the 21 grids from bottom to top represent 21 ascending semitones reaching from the lowermost square to the uppermost. Thus, the grid lets each ‘picture’ express a potential range of sounds spanned by a register of 21 semitones and a duration of 28 beats, made up of only whole notes. The images can thus be played with the mechanical logic of a musical score from left to right – just as one imagine they would have been if the paintings had indeed been fed through a barrel organ in accordance with Richard Winther’s original idea. The graphic score indicates neither tempo nor a specific tonal anchoring, but from the printed sheet music and the recording from 1971 it can be ascertained that the performance uses the notes from c to g# and a tempo of 60, which corresponds to each square, each whole-tone step, lasting one second.

The choices made to carry out the translation from painterly image to sound constitute the conceptual engine that generates the specific form of the sound work and its sonic characteristics. A logic which, when first put into action, appears mechanical, yet is nevertheless based on a series of aesthetic choices – choice of instrumentation, tonal material, duration, and conditions governing the performance – that can reasonably be described as alien or arbitrary in relation to the actual principle of construction, as much so as the various painting techniques and pigments Aagaard Andersen used in the series of paintings.

Whereas Winther, in Machine Symphony No. 2, takes the working method used to construct his painterly images based on the physical dimensions of the medium and applies this to the creation of a work on the lacquer disc medium, Aagaard Andersen can be said to take a detour around the imagery of his paintings to arrive at Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector. A detour that is not so much about a transfer of a method as it is a translation of a two-dimensional image logic into sound extending in time, based on a set of parameters that appear more or less arbitrary.

Speaking about the link between Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector and the series of paintings based on the principle of A division of the relationship of the sides, Aagaard Andersen says:

Yes, we quite naturally strayed outside of painting, because there were things that painting could not do when we tried it. I myself got started with music like this: I had these pictures which essentially had to express themselves by means of lines. In order to draw those lines, I had to give the line a thickness. This thickness did not pertain to the line as a mode of expression. Then I tried instead to paint two colours up against the line so that the line became a dividing line, a contour between the two colours – but as soon as I had two colours in the pictures, what happened was that one colour seemed to come toward you while the other receded and became a background, and that was not the intention either. Then I tried to apply the colour as a wash moving away from the dividing line, quickly coming to an end and leaving me with the white canvas – but this just created an even greater illusion of space. And then one day, I said: “There bloody well has to be a way of making a line that’s free of the canvas, standing straight into the air – you must be able to do that through sounds.”

The purpose of the paintings in the series was, then, to visualise the principle of construction in itself without the use of representation and illusionistic depiction. However, it proved impossible to escape what he calls spatial illusion. As observer, one forms the impressions that the painterly-material experiments with different painting techniques are in themselves arbitrary in relation to the principle of construction the artist seeks to embody. And that they – the oils on the canvas – are forever getting in the way, weighing down the principle of construction with their materiality so that it tumbles to the ground time and time again. According to Aagaard Andersen, this leads to such great dissatisfaction with painting’s ability to embody the principle of construction that he has to step outside the realm of painting and into sound, striving there to set the principle free from paint and canvas. He seeks to allow the principle of construction to shed its material garb to stand disrobed, straight into the air [Fig. 8].

Can the line stand in the air, free of the canvas?

In the actual experience of the work, the graphic score would have supported the listening experience with its didactic clarity, allowing the audience to make the connection between image and sound and also make or follow the translation in their mind along the way. In the interview with Grete Aagaard Andersen kept in the SMK sound archive, she contributes her own perspective on how the Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector can be understood in the context of the study of the construction principle found in A division of the relationship of the sides. Specifically, she comments on whether it was possible to visualise the principle of construction in sound:

It is a test of whether it can be done at all, and in fact it can’t, because time comes into play. You can never make something that goes backwards, and whereas visually, you perceive something as a whole, it [the image found in the individual sound pictures] is divided into time intervals. […] He tested whether his theory worked, and essentially it did not. And then he went on painting.47

To Grete Aagaard Andersen’s mind, the experiment ended up being ‘a very big disappointment’ because the listening experience did not succeed in visualising the principle of construction: the audience could not form the same immediate overview as they could in the paintings.48 According to Grete Aagaard Andersen, the experiment of letting the lines stand straight into the air, as Aagaard Andersen put it in 1971, did not succeed: the lines could not remain fixed in the listener’s memory over the course of the 28 seconds devoted to each picture, but had to be supported by the visual overview provided by the slides. Whether the experiment of manifesting the construction principle of a Division of the relationship of the sides was successful or not does not seem to have affected Gunnar Aagard Andersen’s outlook on either this or the other works in the series. He regarded the Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector and the paintings in the series as finished works – even if none of them necessarily succeeded in expressing the actual principle of construction without the materials getting in the way. However, in the interview from 1971, he seems to suggest that Concerto for Five Violins and an Overhead Projector came closest to being successful in this endeavour.49

Discussion

In 1971, Richard Winther introduced the four sound works on the two lacquer discs with this keenly honed statement: ‘It’s not music; this is painters making noise paintings.’50 Winther unequivocally establishes the works’ status as visual art rather than music, thereby directly addressing the question of how the sound works should be heard: as music or as visual art? I let Winther chime in here to return to the question of how works are best heard – the question of what I described in the introduction, borrowing from Barthes, as the filiation of the works.

The historical coverage and analyses of Winther and Aagaard Andersen’s works have aimed to show how the sound works are closely linked with the artists’ other practices. In short, I have argued that the works can be heard and read as integral parts of visual artistic practices. Perceiving them as music would indeed seem natural: they take the form of sound, are recorded in a music studio, use piano and strings in their instrumentation, have the words ‘symphony’ and ‘concert’ in their title, and, in the case of Aagaard Andersen’s work, are (also) written down at sheet music! In order to more closely inspect question of the works’ affiliation, I will conclude by including the thinking of two other art critics and theorists, Clement Greenberg and Hal Foster.

Greenberg identifies a striving towards a liberation from materiality in modernist, anti-illusionist art, one which, according to him, is best achieved in constructivist sculpture. Whether such a liberation from materiality can be realised at all is certainly debatable, but in this context the most important aspect is that this striving also characterises the experiments in sound that I have discussed in this article. Although Greenberg does not address works created in sound, his description of modernism’s ambitions for a liberation from materiality is a significant argument for inscribing these works in sound in an art-historical modernist tradition.

Foster’s criticism of categorical formalism within modernist art theory is also included here to support the argument about the affiliation of Winther and Aagaard Andersen’s works with the art institution. Foster’s argument is that the matter of a given artwork’s belonging to a given category should not be determined by whether it fulfils the formal requirements set by the category, but rather by whether it challenges or relates to these. Forster’s argument is thus comparable to Barthes’ concept of filiation, which is based on the work’s way of performing a relationship of affiliation.

Painting, sculpture, architecture – music?

In his text ‘The New Sculpture’ from 1948, revised in 1958, Clement Greenberg brings together painting, sculpture, and architecture in a discussion of the ‘purity’ that, according to him, all art forms under modernism strive towards. As a result of this striving, the modernist, anti-illusionist work seeks a reduction of physical substance in an effort to free itself from materiality. An ambition that, again according to him, is best fulfilled in Constructivist sculpture, which in his interpretation almost mysteriously becomes pure, weightless nothingness:

To render substance entirely optical, and form, whether pictorial, sculptural or architectural, as an integral part of ambient space – this brings anti-illusionism full circle […] in pictures whose painted surfaces are enclosed rectangles seem to expand into surrounding space; and in buildings that, apparently formed of lines alone, seem woven into the air; but better yet in Constructivist and quasi-Constructivist works of sculpture. […] the constructor-sculptor can, literally, draw in the air with a single strand of wire that supports nothing but itself.51

In the context of this article, making a connection to music seems very obvious, but in Greenberg’s thinking, the non-material idealism that underpins modernism is essentially connected to visuality, ‘sheer visibility’.52 Had this not been the case, his constructor-sculptor could quite easily be reframed as a composer-painter (with com-position understood here in the sense of combination), perhaps especially in light of the fact that for many abstract artists – from Mondrian and Kandinsky to the Danish proponents of abstraction in Linien, for example – music explicitly constituted a model for an objectless, non-referential art. A model that often appears as a metaphor and basis for comparison in texts and work titles, just as a large part of abstract art’s vocabulary about composition, rhythm, harmony, and dissonance is appropriated from music.53

Greenberg’s position can be challenged from several angles. In particular, the last sentence of the quote provided here seems to be a kind of optical-rhetorical sleight of hand, where the physical materiality of the wire dissolves completely to become an immaterial line in the air. The striving towards a free-floating art freed from materiality identified by Greenberg is clearly present in the works treated here. Most clearly in Aagaard’s case, where he sought, in his own words: ‘a line that’s free of the canvas, standing straight into the air’.54 Aagaard Andersen can, however, be accused of the same fallacy as Greenberg by overlooking how sound also, of course, has its own material and not least temporal properties.

Disciplines and problems of category

As regards the question of reading of the works as visual art, I will briefly incorporate the criticism that Hal Foster raises in the book Return of the Real about the categorical formalism represented by the standard-bearers of modernism such as Greenberg and the American critic Michael Fried, who was a student of Greenberg.55 Once again, sculpture is a particularly significant point of contention, in this case minimalist sculpture, which Fried categorically rejected as failed and refused to call sculpture because he believed the works made use of a theatrical element of temporality that definitively moved them outside the category of sculpture.56 Foster points out that the temporality of minimalist sculpture threatens Fried’s outlook on ordered disciplines where a real sculpture must present itself with a definite immediacy, not extend in time. Taking issue with Fried’s disciplinary rigidity, Foster adopts the perspective that minimalism’s challenge to disciplinary order is a deliberate epistemological probing of the category of sculpture, leading him to call Fried’s rejection a category error.57

I believe that we are at risk of making a similar mistake in relation to Linien II’s works if we do not listen for how they fit within the context of the artists’ other practices, and instead listen to them as music on the basis of some overall formal, material considerations in relation to their being created in sound.58 Whereas in minimalism, the object takes on a temporality in its phenomenological relation to the viewer’s body – which is what makes Fried call it theatrical – Winther’s and Aagaard Andersen’s works assume a different, more explicit temporal extent through their substitution of the painting’s oil and canvas with the sound of horns, pianos and violins as a conceptual and (self)conscious challenge and expansion of visual art’s material scope – what one might call its material-space-time-scope.59

In Aagaard Andersen’s case, Greenberg’s thesis about modern anti-illusionist art being characterised by a striving for a liberation from materiality appears quite precisely implemented as a strategy to escape the fact that the paintings repeatedly fell short due to overshadowing what Aagaard Andersen considered the essential aspect, namely the ideal of the principle of construction in itself. They became illustrations rather than an embodiment of the construction principle. In Richard Winther’s case, the artist clearly stated his intentions about expanding painting to incorporate both time and space and thus, as a space-time modulator, making it in step with contemporary times. In both cases, the dimension of time extended in sound is added to the mix.

Conclusion

Through the above, I have tried to establish what could be called an art institutional listening position: a position which adopts the perspective that the filiation of the works addressed there, their belonging in what Arthur Danto calls the artworld, is a decisive premise for understanding their use of forms and materials that otherwise traditionally belong to music. In other words, I have tried to show how the works by Richard Winther and Gunnar Aagaard Andersen treated here belong to a visual artistic tradition. I have sought to demonstrate how the construction of the works, the circumstances of their creation, their addressing of an art public, as well as the artists’ own texts and statements all show the works’ filiation with visual art. If we want to listen to and understand the works, we must also be responsive to how the works position themselves.

The works’ use of sound is fundamentally conceptual in nature, not a material investigation of sound’s essential properties. Rather, it takes the form of signs in a concrete-artistic semantics aimed at addressing and challenging visual arts’ conventions, visual arts’ spaces, visual art’s modes of experience. The works’ use of musical terms and instruments thus also appears as a deliberate and witty appropriation of musical tropes and as part of the works’ rebellion against the institutional conventions of visual arts through non-traditional means appropriated from the vocabulary and toolbox of music.

The sound works’ conceptual experiments with transferring concrete-artistic principles of construction to sound are thus not the peripheral curiosities they have otherwise been treated as. Rather, they may be some of the most radical – and most mischievous – of Linien II’s artistic experiments.

Perspectives for further listening

In the above, the concept of filiation has been used as a methodological tool to explore how Winther and Aagaard Andersen’s sound works challenge the art institution and its traditions. Playfully and belligerently, this rebellion places itself in the wake of the historical avant-garde, interwar Concretism and painterly modernism, and was closely linked to the notion of and belief in artistic freedom – Art with a capital A – and its potential as a constructive creative force in the post-war period. In the upcoming work with the PhD project Dansk lydkunsts historie (Histories of Danish Sound Art), of which this article is a part, I intent to continue listening and thinking on the basis of works and recordings from the SMK sound archive, engaging in an ongoing testing, nuancing and probing of the concept of filiation established here. As applied to the works treated here, the concept of filiation does undeniably have a certain formal and categorical rigidity. How, for example, might the notion of a work’s filiation be challenged by the Fluxus movement (represented in the sound archive by recordings from the Fluxus Festival in Copenhagen in 1962) with its demonstrative interdisciplinary and inter-media mixing of categories of work? Fluxus employed work categories which, in an even more pronounced and methodologically consistent way, appropriated and transplanted formats and conventions between disciplines. Another specific work that pushes and nuances the use of the concept of filiation are two radio broadcasts listed in SMK’s sound archive under the titles Kvinder i kunst I and Kvinder i kunst II (Women in art I and II), produced by artist Kirsten Justesen in collaboration with editor Allan de Waal in 1975, the International Women’s Year for Danish public radio. The status of these radio broadcasts as independent works of art is unclear, but they nevertheless appear as central examples of an artist working with sound. In a future article, I will listen closely to these two broadcasts, where the audio material consists primarily of voices, and where the approach is far more overtly political and concrete. These broadcasts and voices very much have things they want to say, things that are not abstract but very directly concerned with issues of representation and one’s place in the world. A politically engaged artistic work, of which one might perhaps say that ‘the objective is not to depict reality, but to change it’, as is written in Danish across a print by Justesen from the same period. In the context of the present article, such world-changing ambitions (with echoes of Marx) also mirror the grand ambitions that artists from Linien II harboured for the potential of art after World War II: both Linien II and Justesen’s radio broadcasts are artistic practices that aim to change the world, and both are practices that use sound as a material – but do so in very different ways.