Summary

Peter Christian Skovgaard (1817–1875) travelled to Italy in 1869. This article considers and interprets a number of works he created in connection with this journey through the lens of W.J.T. Mitchell’s Landscape and Power (1994/2002). The article analyses how Skovgaard’s works portray the Italian landscape as an idealised construct, one where the subject matter chosen and overall aesthetic both align with Skovgaard’s specific approach to landscape painting. The article also elucidates how these works were subjected to negative criticism as an outcome of the political climate and artistic developments of the time, which have caused this part of Skovgaard’s oeuvre to be overlooked and little recognised for several generations. The article inspects Skovgaard’s works as political constructions that both shape and are shaped by prevailing outlooks on landscape as a concept.

Articles

As a genre, landscape painting had its heyday from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, enjoying a particularly strong flourishing and prevalence in seventeenth-century Netherlands. It eventually declined in the twentieth century, becoming superseded by new artistic genres and media.

In Danish art, the nineteenth century is regarded as the halcyon days of landscape painting, with the artists of the Danish Golden Age as the main practitioners of the craft. Even among these, Peter Christian Skovgaard (1817–1875) is considered one of the great landscape painters of the period. He was regarded as the foremost interpreter of the beech forest,1 a very Danish subject, and indeed his scenes from Denmark found particular favour among critics and art historians. The widespread tendency to describe Skovgaard as a national painter, singling out his Danish motifs for special praise, has meant that the paintings he created in connection with two journeys to Italy – the first in 1854–1855, the second in 1869 – have not received much attention from art history scholars. And if they have, it has almost always been in the form of unfavourable criticism. Also, while Danish Golden Age artists’ travels to Italy have often been treated in art history writing, the main focus has been on journeys undertaken before 1850.2

This article analyses the works that P.C. Skovgaard created in connection with his second journey and does so on the basis of the theories on landscape put forward by the American art historian W.J.T. Mitchell (b. 1942) in the anthology Landscape and Power,3 where he proposes a revisionist theory of landscape painting, positing it as an art form that actively contributes to a cultural-historical and political discourse of power. Landscape and Power does not address Danish art or the Danish Golden Age, but I will use Mitchell’s angle on landscape as a new perspective on Skovgaard’s works in an analysis of his late landscape paintings and their reception.

Landscape painting

In the traditional art historical approach to landscape painting, as exemplified by British art historian Kenneth Clark’s (1903–1983) book Landscape into art4 and Austrian-English art historian Ernst Gombrich’s (1909–2001) article ‘The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape’,5 landscape painting is defined as a genre that arose in the Renaissance in Western Europe in the sixteenth century and had its heyday between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

According to Mitchell, landscape has been perceived from two different perspectives in the twentieth century. The first involves a modernist, visual developmental history of landscape painting as a genre, as per Clark and Gombrich; the second revolves around a postmodern reading of the landscape as a sign that can be deciphered as a text.6 In Landscape and Power, Mitchell takes a different approach, describing landscape as a dialectical triad between ‘space, place, and landscape,’7 which he uses as a conceptual basis for analysing the actual landscape. That concept can be transferred to landscape painting. Mitchell uses ‘place’ as a concrete, physical location; ‘space’ as a ‘practised place’ or site of action which can be activated; and ‘landscape’ as the place experienced as an image.

Mitchell’s approach does not seek to understand what the landscape is or means, but rather what the landscape does — turning landscape into a verb instead of a noun. Mitchell urges us not to think of a landscape as something we look at or as a text we can read, but as a process that shapes social and subjective identities.8 How can Mitchell’s approach be used to analyse Skovgaard’s late Italian landscapes and generate new perspectives on them?

Skovgaard’s journey to Italy

In 1869, P.C. Skovgaard set out for Italy. Less than a year had passed since he had become a widower in July 1868, after his wife Georgia Skovgaard (1828–1868) had died in childbirth along with a stillborn daughter. The journey to Italy was undertaken in the company of Wilhelm Marstrand (1810–1873), who had become a widower in January 1867, and Adolph Kittendorff (1820–1902). The trip resulted in a series of sketches and paintings that still survive, as do some letters that Skovgaard wrote to his family, particularly to his three children Joakim (1856–1933), Niels (1858–1938), and Susette (1863–1937), and to his sister Vilhelmine (1823–1901). These form the empirical basis for this article.

In contrast to his travel companion Marstrand, who visited Italy four times and stayed in the country for several years at a time, Skovgaard only travelled to Italy twice: in 1854–55 with his wife Georgia, and in 1869 with Marstrand and Kittendorff. Reportedly, the influential art historian and long-time professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Niels Lauritz Høyen (1798–1870), had advised Skovgaard against travelling abroad so as not to contaminate his distinctively Danish character as a painter.9

By the 1860s, Skovgaard was firmly established as a mature and recognised artist. In 1860, he had been appointed titular professor; in 1864, he became a member of the Academy; and in 1869, he received the Ancker Grant, which let artists take a journey abroad of at least six months’ duration. It was this grant that he used for the journey to Italy in 1869.

The reception of Skovgaard

The idea of Skovgaard being a quintessentially Danish painter is, as mentioned, a recurring view found in several of posterity’s evaluations of Skovgaard, and one that has influenced both the general understanding of him as an artist and, more specifically, the reception of his Italian motifs.

In the reference work Nyere dansk Malerkunst (Recent Danish Painting) by Sigurd Müller (1844–1918) – published in 1884, only nine years after Skovgaard’s death – the entire chapter on Skovgaard opens with a critique of Jens Juel’s (1745–1802) lack of ability to depict the Danish landscape, because Juel ‘is not interested in that which is distinctly and characteristically Danish and never truly brings the domestic to life in his art.’ Juel’s failure formed a firm contrast to Skovgaard, whom Müller described as ‘the grand master of Danish landscape art’ and proclaimed to be the one painter ‘who depicted the Danish landscape with the greatest fidelity.’10

By contrast, the reception of Skovgaard’s Italian scenes was predominantly negative. The same Müller wrote of Skovgaard, ‘He was a national artist in the true, eminent sense of the word, and indeed […] his native landscape and countryside is the only one he has interpreted with full mastery.’11 Müller further wrote that Skovgaard’s Italian works were ‘too cold in hue and altogether insufficiently “southern” in their atmosphere.’12

The art historian Karl Madsen (1855–1938) regarded Skovgaard’s Italian works as inferior to his Danish scenes, describing them as beautiful, but of ‘very subordinate importance in the overall body of work.’13

However, observers not only noted Skovgaard’s Italian motifs – they also responded to a certain Italian style in his works. The art historian Henrik Bramsen (1908–2002) wrote:

In the years around 1860, Skovgaard’s position as Denmark’s most prominent landscape painter was widely acknowledged, and his activity was extensive […] Here, he had become more ‘Italianising’ than ever before, yet it was presumably precisely in order to be liberated from this stylistic constraint that he travelled to Italy for the second time.14

With this reference to an ‘Italianising’ style, Bramsen is presumably alluding to the artist’s inspiration from the Baroque painter Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), who, although French, produced a large number of landscapes inspired by Italy. Skovgaard regarded Claude as his greatest role model and had seen a number of his works during a trip to London in 1862, accompanied by the aforementioned Marstrand and Høyen. Bramsen further wrote:

He, who had set his course towards an ideal, classical vein of landscape painting at such an early stage, had at the time followed the advice not to travel to Italy when his turn came. On the face of it, thus preventing the child from coming to its mother seems unnatural, yet it is by no means certain that this course of events had a constraining effect on his art. At that time, he possessed a great surplus of creative energy and did not need further stimulation. He himself believed that his art would have been different had he come to know Claude Lorrain in his younger years.15

Karl Madsen believed that ‘In terms of colouristic refinement and beauty, Skovgaard had nevertheless not learnt enough from Claude Lorrain.’16

This late Italian influence, received through the Italian art Skovgaard saw in Italy and the Italianising art of painters like Claude, was thus seen partly as something from which he ought to have learnt more, and partly as something from which he should be liberated. Skovgaard himself saw the fact that he had not been exposed to Italian or Italianising art earlier in life as a loss, one that was detrimental to his artistic development.

In the reception of Skovgaard, there is thus a marked preference for his Danish works in a Danish style, while his Italian motifs or paintings in an Italianising style are less favourably received. This preference for the Danish as opposed to the foreign can be linked to the assessment of Danish Golden Age painters as either ‘blond’ or ‘brown/brunette’, national or cosmopolitan — a dichotomy that became widespread in the aftermath of the First Schleswig War.17 Skovgaard was classified as blond/national, and in older and more recent scholarship alike, analyses of Skovgaard’s work have primarily applied a national/Danish perspective.18 Those artists whose paintings were considered cosmopolitan were largely written out of Danish art history, particularly if they leaned towards a German style.19 Skovgaard was not written out of Danish art history, quite the contrary: he was canonised as an archetypically Danish artist due to his Danish motifs. The focus on national aspects supported by such polarisation has likely contributed to Skovgaard’s Italian paintings being ignored, as they did not fit into the categorical narrative that cast him as a quintessentially Danish and national artist. Even though the above-mentioned writers wrote long after the First and Second Schleswig Wars, it appears that this national perspective has tinted perceptions of Skovgaard and Danish art history for several generations.

In more recent research on Danish painters’ journeys abroad, art historian Karina Lykke Grand (b. 1974) has reintroduced Skovgaard’s Italian works into the narrative by viewing them from a tourism perspective.20 Lykke Grand’s work is also the first instance of Skovgaard’s Italian images receiving a more favourable assessment. She described them as ‘beautiful and competent views of Italian landscapes’ and believed they possess ‘such unsurpassed qualities […] that they ought henceforth to be included as part of the vocabulary for which Skovgaard is known.’21

The above provides an overall impression of the reception of Skovgaard’s late Italian landscapes in his own time and in posterity. The reception of these works is indicative of the general struggle over the direction and development of art that took place in the late nineteenth century and which has continued to influence our understanding of Skovgaard’s Italian works almost up to the present day. It is this struggle over landscape painting which Mitchell’s approach to landscape, its power, and its influence can help us to understand.

Skovgaard’s Italian landscapes

The works that Skovgaard created in connection with his 1869 journey — and which are presented in this section — show variations on certain recurring views, elements, and moods. They emphasise Skovgaard’s approach to landscape as a construct, and how he builds landscapes intended to tell a particular story about the Italian scenery. These paintings, numbering just a couple of handfuls, are the few that are still known today and that can be dated either to the journey itself or to the years immediately after.

In my desire to gain a new understanding of Skovgaard’s Italian scenes, I travelled through the area east of Rome and tried to identify where Skovgaard found his subjects. I sought to follow in Skovgaard’s footsteps and see what he had seen, to walk the paths and roads he might have followed, and in that way become active in the spaces where Skovgaard had once been active many years before me. I tried to photograph the views I recognised from his nineteenth-century landscapes and to make them my own landscapes of the twenty-first century. Beyond the neo-romantic dream of following in an artist’s footsteps, this fieldwork also allowed me to gain a more precise topographical understanding of where Skovgaard had found his subject matter, how these locations were situated in relation to one another, and how art history still shapes our perceptions of these landscapes.

In general, Skovgaard’s compositions are often characterised by the viewer’s and the artist’s vantage point being pulled back. Skovgaard might create a repoussoir on one side, which adds depth but also acts as a screen or protective shelter for the viewer taking in the vista. One is drawn back into safety and able to survey the whole scene. The viewer does not stand at the edge, ready to step into the landscape, into the world, but instead occupies a withdrawn and secure waiting position that offers both perspective and overview — which is, in itself, also a form of power. Towns and cities often act as focal points on the horizon but are kept at a safe distance from the observer. Mitchell writes about how the landscape draws the viewer in, but that this attraction simultaneously creates an aesthetic distance,22 and Skovgaard’s Italian compositions are quite apt examples of this.

In Italy, Skovgaard often chose to paint from a hilltop or a mountain slope that gave him a panoramic view of the Arcadian landscape, surrounded by rolling valleys and framed by blue-tinged mountains in the background. He also most often painted his pictures in the atmospheric light of dusk, with strong contrasts between the illuminated evening sky and the backlit, silhouetted landscape. He especially found his subject matter around the towns of Subiaco and Olevano.

Subiaco

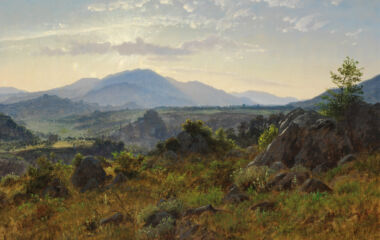

In an undated painting [Fig. 1], Skovgaard depicts the view from a mountain slope near Subiaco, where he stayed in June 1869.

Subiaco, located on a hilltop in the middle of the painting, is backlit, with the fortress Rocca Abbaziale at the very top. On the left side at the foot of the hill we glimpse the church Sant’Andrea Apostolo, and the large, solitary building to the left of Subiaco may be the monastery San Giovanni Battista, one of Subiaco’s many Benedictine monasteries. The view is taken from a mountainside at a point situated below the Benedictine monastery just outside Subiaco, San Benedetto, but above another monastery called Santa Scolastica. The sky in Skovgaard’s painting is light, but darkness is beginning to fall over the landscape. The artist has painted a lush foreground with several plants rendered in bright green against the brown grass, still lit by the sun, while Subiaco’s hilltop stands as a dark silhouette in the middle ground. In this landscape, the town and buildings appear as small, almost insignificant elements within nature.

In 1871, two years after returning to Denmark, Skovgaard painted a larger variation [Fig. 2] on the same subject. Here, the Santa Scolastica monastery appears in the lower left corner, with its tower peeking above the trees. Both versions of the scene show the sun setting behind the mountains, partially hidden behind clouds. In this version, however, the contrast between light and dark is far more pronounced. Whereas the foreground in the first version is still relatively bright, with vividly green leaves on the bushes in the front, the foreground in this second version is much darker. Skovgaard has placed a group of trees on the right-hand side, casting dark shadows across the foreground. In both images, Subiaco appears almost as a translucent dream vision, dissolved in the rays of the sun.

The same mountain range appears in the background of another painting where dusk has grown even darker [Fig. 3], even though the sun still peeks out from behind the clouds. The tower of the Santa Scolastica monastery is still visible in the lower left corner, but the mountain top of Subiaco has disappeared, replaced instead by a stone bench in the foreground. On the right-hand side, a rock formation partly obstructs the view. Here, both Skovgaard and the viewer are positioned almost behind the rock, enclosed within darkness that has settled over the landscape – a deeper darkness than in the earlier painting of the same view. The sun forms god rays that create a supernatural atmosphere. In the foreground, Skovgaard has painted an empty stone bench that underlines the absence of people, but also invites the viewer to step into the image. The bench indicates, to use Mitchell’s terms, a practised place – somewhere one might do something: sit on the bench and thereby activate the space – but also a place where the viewer can imagine sitting or standing, admiring the landscape, thereby making the view their own while maintaining an aesthetic distance from it.

The variations across these three works of the same view — the same landscape — underline how Skovgaard transforms a view into a landscape. He begins with a specific location, using recognisable topographical features that allow the place to be identified, but the different versions of approximately the same view — in which he adjusts various effects such as the lighting, shifts compositional elements like buildings and trees, and adds staffage such as the bench — all serve to emphasise how the landscape is a construct, one that can be altered according to Skovgaard’s vision of what kind of landscape he wishes to depict.

ARoS, inv. no. Painting 528. Photo: Ole Hein Pedersen.

Olevano

Skovgaard’s images from the smaller town of Olevano, a few kilometres west of Subiaco, display greater variation in terms of subject matter. Like Subiaco, Olevano is built on a hilltop. In one evening scene [Fig. 4], Skovgaard depicts Olevano from a position behind the summit of the mountain, looking westward towards the ruins of a castle with a watchtower, an edifice built by the Colonna family as a fortification at the very top of Olevano. In the background are the Volsci Mountains. In the foreground are scattered trees, possibly olive trees or perhaps the oak trees for which the local forest, known as La Serpentara, was famous. In addition to the oaks, La Serpentara was also known for its pale chalk rocks protruding from the ground – as represented by Skovgaard at the bottom of the canvas. The small study shows the mountains as a blueish-violet silhouette behind which the sun has already set, though it still manages to illuminate the sky with golden rays.

The La Serpentara forest was so named after the many snakes (serpenti) in the area. In connection with the expansion of the railway system initiated by the Italian state in the 1860s, there were plans to cut down the forest in order to use the oak timber for railway sleepers. Olevano had been frequently visited and depicted by German-speaking artists ever since the Austrian painter Joseph Anton Koch (1768–1839) and the German ditto Franz Kobell (1749–1822) first arrived there at the end of the eighteenth century. For this reason, the German national authorities elected to purchase the forest in 1873 in order to preserve it. In 1906, the German sculptor Heinrich Gerhard built a small house as a residence for German artists. In 1914, he donated the house to the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin.23 The house — albeit in a new, rebuilt version — is still used for German artist residencies today. It is interesting that while the Italians saw La Serpentara as a place where one could obtain valuable raw material, the artists’ depictions of La Serpentara made Germany wish to preserve the forest as landscape and ensure that German artists could continue to visit and experience it as such.

67 x 102 cm. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. no. MIN 0946. Photo: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

From the La Serpentara area, Skovgaard painted another picture [Fig. 5], where he looks north toward the town of Civitella, today called Bellegra.24 The painting is dated 1870, the year after Skovgaard’s return to Denmark, which means it must have been based on drawings or studies – though no such preparatory works are known today, despite the National Gallery of Denmark and ARoS each owning one of Skovgaard’s sketchbooks from the journey.25 It is the only one of Skovgaard’s paintings in which people and animals appear, thereby illustrating how this place is actively used by shepherds allowing their goats to graze there. Mitchell writes about how showing what a landscape can be used for — showing labour taking place within the landscape, or viewing it as real estate with monetary value — is the antithesis of landscape as medium.26

La Serpentara was not the only place the Germans wished to preserve as landscape. Nearby lies the Casa Baldi, which is also owned by the German state and functions as an artists’ residency venue.27 Even in the days when Skovgaard was in the area, the house served as guest accommodation for travelling artists. Skovgaard, Marstrand, and Kittendorff were presumably meant to stay at Casa Baldi: upon arriving in Olevano, he wrote the following to his sister: ‘The place where we supposed to stay was quite dismal, overcrowded with Germans, so there was no room for us.’28 Even so, Skovgaard must have spent some time at Casa Baldi: the view from there appears in several of his paintings. One of these, Mountain Landscape with Olive Trees near Olevano [Fig. 6], depicts the view from the terrace in front of Casa Baldi, with the Volsci Mountains in the background. In the foreground, an olive tree rises up prominently. In another variation of the same view, the olive trees have been allowed to dominate [Fig. 7]. The trees appear as a silver-green veil in front of the pale blue sky and the hazy vista of the Volsci Mountains and the Sacco Valley. These two works offer a definite contrast to Skovgaard’s other twilight scenes.

Oil on canvas, 36 x 59 cm. The Nivaagaard Collection, inv. no. 152NMK. Photo: Public domain.

In a third variation on the view from Casa Baldi, we once again find ourselves at a time of twilight — but this time it is the twilight appearing before sunrise rather than at sunset. Here, the olive trees are gone, and the view from Casa Baldi is unobstructed [Fig. 8]. The sun is about to rise, but in contrast to the two previous paintings, which were bright and illuminated by the sun, Skovgaard opted for a markedly darker image here. The foreground remains in shadow, as yet untouched by the rays of morning light, while the horizon is only just beginning to be illuminated by the rising sun. Human presence is indicated only by the columns of smoke rising in the distance. In yet another variation [Fig. 9], Skovgaard depicts what at first glance appears to be same view, this time from a slightly more northerly position. Here, he looks southward from La Serpentara toward Olevano, its castle tower appearing in the centre right of the image, and Casa Baldi a little to the left of the town. Skovgaard labelled the study Civitella, but he must have found the scene on the road between Olevano and Civitella, not from within Civitella itself.

Skovgaard depicts these places as landscapes relatively untouched by humans or human activity. Only a few towns or buildings appear in his scenes. From some houses, plumes of smoke rise from chimneys as evidence of life and activity inside the houses. No people appear, apart from the goatherds. Skovgaard’s landscapes can be viewed passively, contemplated with an aesthetic distance – they do not depict fieldwork, forestry, or any other active occupation in or use of the landscape.

Skovgaard’s constructed landscapes

As we have seen, the aforementioned paintings represent Skovgaard’s use of deliberately constructed landscapes where certain elements are repeated and reused while others are varied or replaced. Skovgaard’s landscapes encompass a specific repertoire on which he turns out variations, shaping its manifestations depending on what he wants his landscapes to do. This repertoire is an idealised, Arcadian impression of the Italian landscape. They are a representation of a representation, or, as Mitchell writes, landscape is ’not simply raw material to be represented in paint, but is already a symbolic form in its own right.’29 Skovgaard’s landscapes are symbolic forms that express specific meanings and values.

Thus, the gaze with which Skovgaard views the Italian landscapes is not innocently untinted, the gaze he employs while creating his works is not without impact, and the gaze with which his works are judged by critics is not neutral. In Skovgaard’s letters from the journey, we are given an impression of how the trip unfolded, what the three artists saw, where they stayed, and also a little about how Skovgaard constructed his landscapes. In a letter to his children back home in Denmark, Skovgaard writes about his stay in Subiaco and Olevano:

Here we have the loveliest weather one could wish for, not too hot, and a sky so finely blue and so beautiful, and mountains also blue and shimmering in many colours; I am working hard, both in the morning and the afternoon […]30

In a letter to his sister, Skovgaard writes:

There is plenty to paint here, everywhere is beautiful, but it has been hard for me to grasp it; however, I am pleased with what I did last night, so I hope that I will fare better from here on, it is difficult to pick out something from such an overabundance of choice.31

Yet this was exactly what Skovgaard did: he ’picked out’ specific subjects or motifs amongst all that he saw during this journey. Mitchell would say all artists do this. Skovgaard creates landscapes that give us the impression of actually being there – or potentially having been there – and that we might well be the viewers looking out at the scene. They offer us the voyeuristic pleasure we are coded to feel when we look at a landscape as active observers while the landscape passively receives our gaze.32 According to Mitchell, we claim that ‘landscape is nature, not convention’ in the same way that we claim that the landscape is something ideal and not merely land that can be traded. The landscape is a construct that hides its own artificiality; a landscape painting is likewise a construction that conceals its conventions and stereotypes behind a veil of apparent naturalness.33

Political landscapes in Denmark and Italy

Just as Skovgaard painted Arcadian depictions of the Danish landscape, his Italian landscapes also represented a particular perception of Italy. Skovgaard’s Danish scenes showed a carefully selected aspect of the Danish landscape. And the Italian scenes created by Skovgaard in no way revealed the transformations that Italy was undergoing during this period. Skovgaard travelled at a time when Denmark was still feeling the aftershocks of its defeat in the Second Schleswig War in 1864. Denmark needed to restore its national pride and re-establish its national identity after the loss of North Schleswig. Italy, by contrast, was a country that had been recently unified: in 1861, the appointment of Victor Emmanuel II as king of the realm began the transformation of Italy, reshaping an array of separate countries with different forms of government into a modern nation where a new shared identity was to be created, and where the cities were growing. The starting points for Denmark and Italy were very different, but both – like several other European countries – were fully engaged in ‘nation building’34 during this period.

In 1850, a few years before Skovgaard’s first journey to Italy in 1854–55 with his wife, the population of Rome was 170,824 inhabitants, but by 1870, the year after Skovgaard’s second visit, that figure had risen to approximately 226,000 inhabitants.35 The major cities began to be modernised, as was reported in a letter home written by Skovgaard’s travel companion, Marstrand: ‘Here in Italy, they are building and chiselling in marble with great vigour […] — viaducts, bridges, paved roads, churches, monuments, and so on.’36 A new, national infrastructure for communication and transport was being built. In 1862, the postal service Poste Italiane was established, and in 1866, the first horse-drawn omnibuses were introduced in Rome. Street lighting with petroleum lamps was gradually replaced by gas lanterns, of which there were 2,000 in Rome by 1870. The railway station inaugurated in Rome in 1863 proved inadequate in scale after just one year, prompting preparations for a new station that commenced service in 1870.

Skovgaard did not write about the political conditions in Italy or the changes found there compared to his first stay in the country. However, in a letter from their joint journey written by Marstrand to his brother Troels, Marstrand put forward the following opinion:

Here in Italy, the state of things is quite muddled. While it is true that the new order of things has brought some benefits, there is much yet to put in order, especially as the majority of the common people is indifferent to progress and still lives in the darkness which the priests have successfully cast over their minds, even though those minds ought to be capable enough. It is surely a land, and people, endowed with extraordinarily rich gifts by nature, but equally surely it is quite immature and as yet incapable of governing itself. With us, the upheaval went so smoothly because we had an honest and educated civil service, but here, most of them are scoundrels.37

Marstrand’s criticism of the political and religious conditions in Italy compared to those in Denmark are quite telling, revealing Marstrand’s own mindset and the national sentiment of the period. Marstrand and Skovgaard had both been involved in the introduction of a new constitution in Denmark and were close friends with several members of the constituent assembly, who also commissioned works from Skovgaard. The political landscape that Skovgaard encountered in Italy was entirely different from the political landscape at home. Because Skovgaard was involved in political issues in Denmark, and because he travelled to Italy with a companion who was likewise politically engaged, we may assume that discussions of the political and social atmosphere in Italy also occupied Skovgaard’s thoughts, even though – unlike in the case of Marstrand – we have no surviving written sources that directly substantiate this.

While Skovgaard was certainly interested in political and societal aspects, a different kind of cultural outlook on landscape guided his artistic gaze away from depicting the changes that the Italian landscape was undergoing. Skovgaard’s Danish and Italian landscapes both convey an impression of the landscape being quite ’natural’ – unspoilt and original. An idealistic and idyllic narrative of landscape which promotes a specific idea of the nature of both countries – one quite far removed from reality.

Skovgaard’s landscapes make us imagine the Danish and the Italian landscapes in a particular way, striving to make it appear so natural that the illusion is easy to fall for and believe in. We so fervently wish to believe in the landscape as something beautiful, paradisiacal, Arcadian, even though the reality – then and now – was one of population growth, rising tourism, industrialisation, expanding infrastructure: a process of modernisation, utilisation, and urbanisation of the landscape that left very little – if anything? – untouched by human hands.

Mitchell writes: ‘Landscape painting is best understood, then, not as the uniquely central medium that gives us access to ways of seeing landscape, but as a representation of something that is already a representation in its own right.’38

When Skovgaard depicts the Italian landscape, he creates a representation of something that is already a representation of cultural significance, one already infused with particular values. An Italian landscape is encoded with the idea of being something other than a Danish landscape. Even before Skovgaard sets his pencil to paper or his brush to canvas, the landscape he observes is artificial. As soon as he perceives it as a subject that can be painted as landscape, the landscape is already a representation and not just nature. Before Skovgaard even arrives at a place in Italy, he already has a notion of what kinds of places and spaces lend themselves well to being depicted as landscapes based on the Romantic European landscape tradition. Only certain types of nature pass muster for Skovgaard, only certain types are worthy of being depicted as landscape, and this affects his outlook on Italy and his choice of subject matter, as exemplified by the aforementioned works. These are the types that offer up distinctively Italian traits such as mountains, valleys, or olive trees. The types that were – or could be depicted as – sufficiently ’natural’ or ’untouched’ to convey an aesthetic ideal. Mitchell would say that Skovgaard, like other landscape painters, turns the landscape into a commodity that can be sold, and sold at the right price, if it is ‘packaged’ or presented in a way that suits the buyer’s and the market’s taste.39 This also requires us to assume that Skovgaard does not select his subject matter purely out of inclination or inspiration, but based either on actual commissions from clients asking for particular scenes or based on reasonable expectations about what customers, critics, or the public wanted from him.

According to Mitchell, landscape is a medium filled with symbolic forms that can be drawn upon to express meaning and values.40 The meaning and values that Skovgaard expresses in his late Italian landscapes are clear: he presents the Italian landscape as aesthetic and atmospheric scenes of great beauty. To my contemporary eye, they are no different in nature or quality from Skovgaard’s Danish subjects, even though in Skovgaard’s later reception, critics were unfavourably disposed towards them. In this regard, I believe that their firmly entrenched ideas about Skovgaard, pigeonholing him as a Danish painter, prejudiced their ability to assess Skovgaard’s Italian subjects on equal footing with his Danish ones. This reveals their nationally-minded approach to Danish art in general and to Skovgaard in particular: to their minds, it was impossible for an artist whom they perceived as the very incarnation of Danishness to depict a foreign landscape with the same earnestness and authenticity as a Danish one, no matter how hard he tried.

Skovgaard seen through Mitchell’s lens

If we transfer Mitchell’s approach of ‘place, space, and landscape’ to Skovgaard’s paintings, his triad gives us the opportunity to analyse Skovgaard’s landscape paintings on a broader, more overall level that goes beyond their reception. We are given the opportunity to focus on how Skovgaard constructs subjects with a specific effect in mind.

Skovgaard travels to particular places, and his scenes incorporate recognisable topographical elements from the places he observes. However, the aim or intention of Skovgaard’s paintings is neither to document the place in question nor to engage with the activities set against the backdrop of the specific space. Skovgaard’s objective as a landscape painter is to create a construct, a landscape where the characteristics and activities of the place – or lack thereof – are used to create a convincing depiction of a concept, that of the ideal Italian landscape. Skovgaard’s landscapes are predominantly devoid of people, but he does insert traces of human activity that help create a sense of depth and proportion, and also allow the viewer to identify with or immerse themselves in the subject, without losing focus on the landscape itself.

Mitchell would analyse the landscape painting as a manifestation of cognitive encounters with a place, reading what the landscape painting tells us about a place, or what symbolic characteristics it contains.41

Skovgaard created his depictions on a working trip, during which he and his travel companions visited various cities and sights as part of their general education and enlightenment as cultured artists, and stayed in certain places for longer periods to produce works. This was only his second journey to Italy, and he himself assumed it would be his last visit to the country.42 His objective, then, was to find as many suitable subjects as possible and capture them in his sketchbooks or on smaller canvases, so that upon returning home he would have firm foundations for producing larger, carefully finished paintings.

By turning to Mitchell’s concept of the cognitive encounter, we can understand Skovgaard’s interaction with the Italian landscape as a reading and transformation of a place, where what he perceives as beautiful views of valleys and mountains, atmospheric lighting, and uninhabited landscapes are deliberately selected and used as the basis for constructing specific scenes and subjects.

Skovgaard’s cognitive encounter with the Italian place and space in 1869 is, for him, an encounter with places and spaces that many other artists had visited and depicted as landscapes, ones which he can translate into landscapes that possess market value in Denmark and artistic value for him as an artist in terms of furthering his career. Skovgaard’s encounter with place and space is influenced by the fact that they must be transformed into a landscape. His choice of subject and composition is thus based on an assessment of what fits into his landscape paintings. Skovgaard sees specific places, he sees certain spaces, which he himself and others – locals and tourists – activate, but his cognitive encounter with them is what turns them into landscapes. In his work, this is the gaze he practises, and he translates what he sees into landscapes that can be consumed by viewers who see and potentially purchase his works at exhibitions. Skovgaard designs his landscapes to be consumed as artworks.

This marks a break away from romantic, innocent notions that Skovgaard chooses and creates landscapes based purely on the places that immediately speak to him or solely on what he literally sees. He does not passively or neutrally reproduce the Italian landscape: rather, he is himself embedded in it and contributes to shaping a particular impression of the Italian landscape that fits within his oeuvre and is typical of the artistic style and aesthetic of the time. Parallels can be found in other Danish and European artists, but also in Skovgaard’s Danish works. Overall, Skovgaard depicts the Italian landscape as fairly untouched by human hands, with few traces of human influence on the landscape and few figures in his compositions. He represents the Italian landscape as a construct, an accumulation of all things Italian – such as olive trees, mountains, and valleys. He creates an incarnation of the Arcadian landscape, an artificial world that resembles a natural one, which is the very nature of Romantic landscape painting – to make a constructed perception of landscape, shaped by the cultural and political constructs of the time, appear natural.

This analysis is not to be understood as a reading of Skovgaard’s conscious modus operandi. Rather, the purpose, using the concept of the cognitive encounter and Mitchell’s triad more broadly, is to emphasise how landscape painting emerges out of an interaction between concrete places and culturally determined norms: the cultural norms are embedded in the artist, shaping his outlook, and the places, in turn, lend credibility to the cultural constructs and help these appear as natural givens. As Mitchell writes: ‘Landscape […] naturalizes a cultural and social construction, representing an artificial world as if it were simply given and inevitable.’43

If the landscape painter transforms culturally determined perceptions into the ‘simply given’ or naturalised, we should take note of the fact that Skovgaard’s Italian landscape paintings were apparently not received as given and natural by contemporary critics. As I have outlined, Müller questioned the credibility of Skovgaard’s Italian landscapes in 1884. Taking Müller’s criticism as a point of departure, we can propose the hypothesis that the general perception of Skovgaard as a quintessentially Danish painter meant that the critics could not or would not be convinced by Skovgaard’s Italian subjects as genuine or credible, precisely because his entire credibility was built on his national character. For the critics, Skovgaard’s Italian paintings were not ‘simply given and inevitable’ when they saw him only as a Danish painter. If one looks at Skovgaard’s production of Danish subject matter during the same period, the similarity in approach between his Danish and Italian motifs is evident.44 In his own day, when Skovgaard was known as the pre-eminent interpreter or mediator of the Danish landscape, it may have been unacceptable to see this interpretive ability transferred to other subjects, precisely because it then became visible as a deliberate approach, a technique or construction. Because Skovgaard transfers a Danish space onto an Italian place, his Italian landscapes appear unconvincing and inauthentic to Danish art critics. Perhaps Skovgaard’s Danish landscapes were credible constructs in the eyes of a Danish audience, while the Italian landscapes did not generate the sense of identification or recognition that made Skovgaard’s Danish landscapes so well beloved.

Conclusion

The general perception of Skovgaard as a national, quintessentially Danish painter has caused his Italian scenes to be almost entirely excluded from significant or positive attention in art historical literature. With this article, I wanted to examine this particular chapter in Skovgaard’s late work through W.J.T. Mitchell’s approach to landscape. I have selected works that Skovgaard created in connection with his second journey to Italy because they embody certain issues concerning Skovgaard’s landscape paintings that I wished to approach differently than the existing literature. The set of issues is not limited to this small and late chapter of Skovgaard’s oeuvre, but it is a chapter that can be used to raise some more general points about Skovgaard as a landscape painter, as well as about the reception of Skovgaard. This contributes interesting facts about the nationalistic discourse of the period and helps reveal the historical premises for how the quality of a particular period in an artist’s body of work is assessed. This chapter of Skovgaard’s oeuvre tells us something about a time of transition in Danish art in the nineteenth century and a time of upheaval in Danish politics: it says something about how landscape painting represents this struggle and how the reading of landscape painting is tinted by politics and by our own ambivalent relationship with nature as landscape.

Skovgaard travelled to Italy in his capacity as a Danish artist and seized hold of the landscape as an artist intent on shaping it into a particular image – based on his own perception of Italy, his perception of Denmark, and his understanding of what landscape painting was meant to convey. The negative reception of these late Italian works demonstrates that Skovgaard did not manage to shape the landscape in a way that resonated with art critics in his native Denmark. Unlike many other contemporary Danish artists’ earlier depictions of Italy, Skovgaard’s landscapes were not incorporated into the narrative of the Danish Golden Age or of the National Romanticism movement. This may have had less to do with their quality and more to do with the state of the Danish art scene at the time – both from Skovgaard’s perspective and that of his critics. Mitchell’s triad of place, space, and landscape thus provides us with a tool that helps us cast a new light on Skovgaard’s landscapes, thereby offering a better understanding of the struggle played out within them.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces for supporting a research sabbatical that made it financially possible to write this article. I am also grateful to the Danish Academy in Rome for granting a residency which provided the necessary peace and quiet to study letters, literature, and artworks, and to write. My sincere thanks go to Marianne Nordby for her generous hospitality and invaluable assistance in the search for Skovgaard’s chosen subjects in Olevano, Subiaco, and the surrounding area. Finally, my thanks go to the board and staff at Ribe Kunstmuseum for allowing me to complete this article while transitioning from the Skovgaard Museum to Ribe Kunstmuseum.