Summary

In 1854, Danish newspaper Dagbladet proclaimed the existence of two cliques on the Danish art scene. The following year, Dagbladet described the two factions as, respectively, ‘National’ and ‘Cosmopolitan’, asserting that both Marstrand and Skovgaard belonged to the National camp. However, closer inspection of their overall choice of subject matter, letters, networks and international travel shows that the two artists were not preoccupied with quite the same national cause. Skovgaard wanted to actively use his art to affect the development of society. Marstrand, on the other hand, did not wish to mix art and politics. The article highlights how a critical look at the fixed dichotomies of art historiography can unlock entrenched ideas, expanding our knowledge of how artists collaborated, quarrelled and evolved in their own time.

Articles

The artist Peter Christian Skovgaard (1817–75) visualised Denmark as a land of clear, blue skies arched above idyllic landscapes revealing no signs of European revolutions, Schleswig wars or internal conflicts on the art scene. In the works of fellow artist Wilhelm Marstrand (1810–73), the mood ranges from cheerful scenes of Italian folk life to solemn history paintings. Marstrand’s depictions also reveal little of the tensions that were such a prominent aspect of nineteenth-century Danish society’s discussions on politics and art. Among these we find the professional controversy reportedly found on the Danish art scene, one which the newspaper Dagbladet described, in 1854–55, as a quarrel between two cliques: the ‘National’ and the ‘Cosmopolitan’ artists.1

In 1854, the newspaper specifically named fifteen artists as exponents of the two factions, among them Marstrand and Skovgaard, who were described as being part of the National clique. The painters had not chosen to appear on this list themselves; they were assigned their places by Dagbladet’s unnamed writer on the basis of their art, their prominent positions as exhibiting artists and their personal affiliations. The importance of their political leanings can also be inferred by looking at the networks and media to which the relevant artists are linked. Historiographic studies have shown that over time, this division into cliques has become crucial to the general definition of who was considered ‘in’ and ‘out’ in Danish art history, and that this dichotomous view forms the backdrop for the canon that has since prevailed.2

Danish art history has been remiss in addressing the Cosmopolitan artists, both at the museums and in literature, but interest in these excluded artists has been on the rise ever since various turns within academia since the 1980s have demanded a more diverse perspective on the past.3 Marstrand and Skovgaard were both listed as exponents of the National clique, despite their differing perceptions of what national art really was and should be used for. While Marstrand and Skovgaard are part of the category of artists who have been regularly addressed in Danish art history, the studies conducted so far have primarily applied an art-historical focus and can be usefully supplemented by a cultural-historical contextualisation. In addition, the rigid dichotomy of National and Cosmopolitan artists has not prompted anything in the way of a critical comparison within the group of supposedly National artists.

This is perhaps surprising, given that as far back as 1905, the influential art historian Karl Madsen (1855-1938) pointed out that Marstrand’s conception of the distinctly Danish aspect of Danish art differed from the general conception of ‘the national’ that Dagbladet attributed to one of the cliques, an outlook particularly spearheaded by the art historian Niels Lauritz Høyen (1798–1870) in the mid-nineteenth century.4 Seen in the light of the supposed cliques presented by Dagbladet in 1854, how should we understand what constituted ‘National’ art in Marstrand and Skovgaard, respectively?

By considering the supposedly ‘National’ artists through the lens of public art criticism, it will be easier to see how the discussion on the national in art was also closely linked with other discussions pertaining to ideas of the national during this period. Comparing pictures and letters by Marstrand and Skovgaard shows how the art world of the day actively negotiated the general perception of what constituted national art. Moreover, it points to how the negotiations taking place within the framework of the group designated as National should also be seen in the light of the era’s more general tendencies in terms of politics and the history of mentalities. Historian Claus Møller Jørgensen has demonstrated how the period’s ideas about Bildung involved a similar clash between the concepts of civilisation and nation: the classical education/Bildung rooted in antiquity and European cultural history was challenged by a new ideal which instead tended to draw on ideas associated with the nation, the people and a more local past.5 This new, national ideal of Bildung is interventional and insistent because it is not satisfied with being confined to the history of ideas: it actively requires political action and development.

The Dutch cultural historian and theorist on nationalism Joep Leerssen’s theories on nineteenth-century transnational cultural centres and the period’s cultivation of national culture will serve as a recurring lens in the following efforts to discern the nuances of divergent perceptions of ‘the national’.6

Dagbladet’s groupings in 1854

In 1854, the Copenhagen-based newspaper Dagbladet ran an article about ‘factions’, ‘cliques’ and ‘camps’ in the Danish artist community – unattractive concepts in an age when individuality remained an ideal.7 At this point in time, it was quite common for art-related news to make headlines and for reviews to take up column space on a par with political news. The annual public exhibition at Charlottenborg, where the artists associated with the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts exhibited their work, was treated to particularly thorough attention in the newspaper’s art criticism. The discussion concerning cliques and rifts on the Danish art scene was sustained in the following years and spread to other newspapers published in the capital, including Flyveposten and Fædrelandet. The political standpoint of Flyveposten was predominantly conservative, while Fædrelandet was part of the National Liberal movement. The art debate was of considerable scope and highly influential, meaning that it should be incorporated into our overall understanding of the developments in art and cultural policies in nineteenth-century Denmark. Accordingly, I will offer a comprehensive account of this debate as the framework for the research conducted here.

According to Dagbladet’s article from 3 April 1854, the Danish art world was home to two leading groupings: the ‘Brunettes’ (or ‘Brown Ones’), who employed a dark palette and mainly looked to the European art scene for traditional subjects and who, the following year, were referred to as ‘Cosmopolitans’ in the same newspaper; and the ‘Blonds’, who used a lighter palette and wished to set their work apart from the more established art tradition in order to assert a distinctly national vein of art; the following year, Dagbladet described them as ‘National’. Dagbladet also points out how the division between the two artists’ groups found expression through their allies: the Blonds are linked to Selskabet for Nordisk Kunst (the Society for Nordic Art) and Fædrelandet, while the Brunettes are associated with Kunstforeningen (the Copenhagen Art Society) and Flyveposten – institutions and media who were known as representatives of conflicting (cultural) political positions in their own time, too. Indeed, Fædrelandet was allowed to play a prominent role as a prop in Marstrand’s Double Portrait of the Merchant Christopher Fredenreich Hage and his wife, Christiane Annete, née Just (1849–52) [fig. 1], where the newspaper can be seen prominently flung over a handrail in the merchant’s study. Its presence can be interpreted as a general nod to the National Liberal circle of which the Hage family was a significant part, but it may also be a more direct reference to the couple’s deceased son Johannes Hage, who was briefly editor of Fædrelandet but reportedly committed suicide after having been subjected to censorship in 1837.8 In the 1840s, the couple’s sons Hother and Alfred Hage were both part of the editorial staff at the newspaper.

In the article of April 1854, Dagbladet emphasises that the artists specified might not consider themselves part of a specific group, a particular ‘us’, but also asserts that the self-same artists are allegedly fond of setting themselves apart by designating other groups as ‘them’. Dagbladet claimed to simply be an observer pointing out how the two cliques were championed and defended by Fædrelandet and Flyveposten respectively. However, the two newspapers thus accused maintained that their art critique was based on purely professional grounds, not political motivations. In actual practice, however, the (culture)political views of the two dailies are quite apparent in their regular art criticism, lending weight to Dagbladet’s claim.9 Flyveposten had actively participated in the art debate prior to 1854. However, in 1854 they ran only a brief, patronising comment on the debate as a follow-up to a review of that year’s Charlottenborg salon in which the newspaper mainly praised the Cosmopolitan artists as per usual. However, the 1855 Charlottenborg exhibition saw Flyveposten print an unusual review presented as a conversation between an ‘art critic’ and an ‘art lover’. While this conversation was not overtly linked to the newspaper debate, it quite specifically addresses the conflicting positions.10

Whereas the Cosmopolitan camp based its endeavours on the traditional European art scene, making it more explicitly transnational, Dagbladet points to the art historian N.L. Høyen as the ideological vanguard of the Nationals and the dawning aversion to all aspects of art that appeared to have their origins in Germany. Høyen was an omnipresent and very influential art historian who was co-founder of Kunstforeningen (The Copenhagen Art Society, 1825), served as professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (from 1829), as curator at the Det Kongelige Billedgalleri (The Royal Picture Gallery, from 1839), was a co-founder of Selskabet for Nordisk Kunst (The Society for Nordic Art, 1847), and a professor and co-founder of the arts department at the University of Copenhagen (from 1856). In addition, he gave semi-public lectures on art in the homes of politicians, intellectuals and businessmen, and was invited on at least two occasions to enter politics via the parliamentary system (1848 and 1853).11 Høyen exerted significant influence and succeeded in steering several artists of the time in a more national and Scandinavian direction, not only in a political and academic sense, but also in purely practical terms, prompting them to use Denmark and Scandinavia as destinations for their professional Grand Tours instead of regarding Rome as their obvious and primary geographical and academic destination for study.12 His position of power also made him controversial and a target of criticism and attack. In May 1847, July 1849 and April 1850, Flyveposten ran very explicit attacks against Høyen, protesting that he favoured the National clique at the expense of other artists.13

Using a term employed by Joep Leerssen, Høyen can be defined as a multitasker because his ambitions for art were both cultural and political in scope and because he was a weighty authority who had the attentive ear of politicians, the business community, artists and citizens in general.14 Hence, Høyen is an important piece of the puzzle for anyone seeking to understand the divergent conceptions of the idea of ‘national art’ seen at the time. Høyen wanted the artists to create a distinctively national art, and as part of this active striving to develop a specific ideology he urged artists to travel around Denmark in order to portray the peasants and the landscape and to visualise Norse mythology.15

Høyen acquired a number of contemporary works for the Royal Picture Gallery (now the National Gallery of Denmark). We can also glean from the catalogues detailing the annual juried exhibitions at Charlottenborg that the buyers and commissioners of works by the seven ‘National’ artists included many National-Liberal politicians and business people. In those cases where the ownership of a given painting is stated in the exhibition catalogues, a very explicit link is established between sender and user, clearly signalling the buyer’s cultural and financial capital. Such information awakens interest in present-day observers, and may also have done so back then. Links of this nature may be read as an expression of the individual artist’s political affiliations or as a political message sent by the buyer, who may have had a vested interest in having their particular political convictions visually presented in their home or in their official reception rooms. Writing on this topic, sociologist Athena S. Leoussi states that: ‘national art is the work of cultural elites whose aim is to organise, unify, streamline and standardise, and, in this way, “modernise” pre-existing ethnic identities and solidarities’.16 Thus, art was also purchased in order to visually and materially manifest a bourgeois political ambition; buyers could actively use art as a means of communication.

These artists travelled extensively and for long periods of a time, which means that we have access to quite a lot of surviving letters relating news of various kinds, big and small, from Denmark and abroad. The letters sent by Marstrand to his friend and fellow artist Skovgaard in Rome over the course of 1854 and 1855 make no mention of the articles in Dagbladet – but Marstrand does articulate his belief that artists should work closely together, forming a community where they can support, develop and challenge each other. In March of 1855, he very briefly states that Skovgaard must prepare for what he calls a ‘war’ in the art world (but, unfortunately for this analysis, he has no wish to further bore Skovgaard with that particular issue in his letter): ‘That we look forward to seeing you and Georgia soon goes without saying – but I would ask you to gird yourself, to be prepared to carry your shield and lance forth into the realm of artists, for there is war going on there as there is in so many other aspects of life, and it is difficult to tell what the outcome will be’.17 It is quite likely that this ‘war’ is, among other things, a reference to the conflicts with the politically (mostly) conservative art academy and the squabbles with Kunstforeningen (Copenhagen Art Society), which was also quite conservative and opposed to those aspirations for collecting art and making it widely accessible that Høyen and the other Liberal artists advocated. Marstrand was himself a professor as well as director of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts when he wrote the letter, so he was presumably embroiled in the ‘war’.

The discussion of art in newspapers, private letters and semi-public lectures took place in the same spaces and same columns used for the discussion of more strictly political issues – a link that is also an essential part of the cultivation of culture described by Joep Leerssen.18 The art criticism run by the various newspapers was not neutral; their descriptions of selected works and the choice of which artists to review or ignore very clearly represented opposing outlooks. The debate on art highlights the general interest in the artists, an interest that went beyond the scope of their works – exploring not just how they paint and the quality of that work, but also why.

In what follows, Dagbladet’s articles and lists of named artists from 1854 and 1855 serve as the backdrop for specifically comparing and contrasting P.C. Skovgaard and Wilhelm Marstrand – because Danish art history’s focus on Dagbladet’s dichotomy between two overall groupings has come to overshadow the internal differences and tensions within the two designated groups, even though these tensions have been instrumental in driving specific art historical and cultural developments.

Cultivating culture in times of political turmoil

At the time when the colour schemes and political connotations of Skovgaard, Marstrand and their Danish colleagues were discussed in the Copenhagen-based newspapers in 1854–55, the Danish political system continued its struggle to establish a constitution. In the wake of the turbulent years of European revolutions around 1848, Denmark became a constitutional monarchy and got its first constitution in 1849. The duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenborg and their status as members of the Danish Unitary State (Personal Union /‘Helstat’) was a recurring controversial issue, and the problem of whether the duchies could be incorporated into a Danish constitution resulted in The First Schleswig War (1848–51). The war failed to yield a solution that was politically acceptable internationally, so politicians and other rulers still discussed and contested the boundary between Denmark and Germany in 1854–55. In the shadow of unresolved tensions associated with the duchies and uncertainties regarding the succession to the Danish throne, the Danish constitution was firmly established with the parallel constitution for the Unitary State (Fællesforfatningen) in 1855. The year before, the government headed by A.S. Ørsted (1778–1860) had sought, in vain, to reintroduce conditions akin to absolute monarchy, a move regarded as utterly unacceptable by Marstrand’s and Skovgaard’s National Liberal circles.19

Finding hard, unequivocal evidence of how visual art had a direct impact on such seminal political developments can be quite a challenge – even though it is quite likely that cultural developments were crucial in establishing and visualising imagined communities and, hence, in the mobilisation of political unity. It is easier to see how political developments impacted the visual arts and the art scene. Landscape art saw a particular boom during these years, a trait which art historian Janne Gallen-Kallela-Sirén describes as a direct consequence of the geopolitical discussions and shifts.20 Now, art was called upon to visualise the new territories, and the quantities of landscape paintings presented at exhibitions rose noticeably in the 1840s. It is also a well-known fact that artists influenced each other and the general artistic trends across the various borders of Europe.21 Hence, the artists’ perception of what national art should be like and/or able to achieve should also be seen in light of wider societal developments of which they were part. The discussion of art is not just about art, but also concerns wider aspects of culture, politics and the development of national identities; the efforts to build a national identity will be familiar in many countries. Accordingly, visual art also has a clear place in Joep Leeersen’s concept of culture, posited among what he calls material culture.22

When Dagbladet highlights national art as a particular and exalted position vis-à-vis other types of art, the newspaper takes part in a process that selects and processes cultural modes of expression and presents them as part of a nationalist-oriented discussion of (cultural) politics.23 Leerssen defines such cultivation as being based on the actor’s conscious intention to instrumentalise culture.

By extension of this definition, Høyen and Skovgaard can be regarded as examples of stakeholders who actively disciplined culture on the basis of a nationality-based political strategy. Marstrand, however, did not want to instrumentalise art for anything other than art’s own sake, meaning that he does not take on such a cultivating role. Even so, because the historiography of art history has largely been shaped on the basis of Dagbladet’s list, Marstrand’s art has, over time, been taken to represent the same national-political point of view.

Transnational influences on national developments

Leerssen has argued that the (cultural) nationalism of the period should be considered in the light of transnational movements. Cultural centres and catalysts may reside outside of the national state to which a given artist, politician or scholar belonged.24 In order to understand how the artists shaped their ideas about what constituted ‘national’ art, it is important to study their transnational patterns and movements. In the early nineteenth century, the Grand Tour through Europe to Rome, a journey intended to complete the artists’ education and make them more fully rounded, civilised human beings, was a well-established tradition. However, many traditions were changing these years, including among artists. Their Grand Tours gradually grew briefer, more efficient transport options emerged, the destinations changed, and some artists chose to pursue entirely new paths.

As far as Marstrand and Skovgaard are concerned, it is clear that the two artists had different priorities in terms of travelling abroad: Marstrand travelled several times and spent many years in Italy, while Skovgaard initially stayed in Denmark and only later set out for brief stays abroad, including in Rome. The Danish artists in Rome did not get involved or integrated with their Italian counterparts, preferring instead to spend their time in the company of Danish, Nordic and German colleagues.25 They all socialised freely, and the groupings would not have been nearly as sharply defined as those described by Dagbladet within the confines of Denmark. In Rome, the artists influenced each other and let themselves be influenced by the art and working community they had travelled there to find. In this way, Rome served as a transnational cultural centre defined by professional rather than geopolitical boundaries, one where the artists came together in a feeling of fellowship centred on the arts. Marstrand fits neatly into this almost mythological tale of artists setting out for the magnificent art of Rome, while Skovgaard chose Høyen’s new Nordic path instead.

During this period, no new cultural centre ever materialised within Scandinavia, but a wish to have such a centre emerge is clearly evident in Høyen’s famous lectures Om Betingelserne for en Skandinavisk Nationalkonst’s Udvikling (Concerning the Conditions for the Development of a Scandinavian National Art), given at Skandinavisk Selskab (The Scandinavian Society) in 1844.26 A link between politics and art, as expressed within the context of the Scandinavism movement, is also discernible in the growing rejection of German art as the political conflicts concerning the contested duchies intensified between Denmark and Germany in the 1840s. A marked change from the first decades of the century, when the cultural ties between Denmark and Germany were strong – the art scenes of Munich, Dresden and Düsseldorf in particular are regarded as having been important to the evolution of Danish art.27 Scandinavism accommodated Høyen’s ambitions to strengthen national and Nordic art from the inside, as well as the ideas held by the Scandinavian student movements which met at major Nordic rallies in the 1840s – with the leading National Liberal politician, Orla Lehmann (1810–1870) among the participants.28 Despite the absence of a definite cultural centre in Scandinavia, Skovgaard was still affected by pan-Scandinavian tendencies. This is to say that like Marstrand, Skovgaard was also part of a trans-boundary movement, but the Scandinavism movement was by no means restricted to artists – it was also an explicitly political community.29

Wilhelm Marstrand’s apolitical art agenda

Wilhelm Marstrand travelled through Europe for the first time in 1836, passing through Germany on his way to Italy, where he remained for five years. When travelling back home from Rome in 1840, Marstrand wrote the following passage in a letter to his brother:

You know that nothing big happens in the world without opposition and discord, without elements that clash and fray – either fight or sleep – if one has the power to win the fight, then something good always arises, even if the fighters themselves often perish in the process. In our part of the world, the Academy’s endeavours have put art into the deepest sleep possible, and I assure you that this is the reason why the artists are so loath to return home, preferring instead to eke out a miserable existence as they do out here; but in this they are wrong; I am forever preaching to them that they ought all to return home, for by standing all together we might accomplish something; just by standing tall together we would collectively form an authority against the existing state of affairs, without false modesty or bitterness, simply by retaining our independence.30

Marstrand is, then, convinced that it is time for a change in the Danish art world – and that effecting such change requires a joint effort against the status quo. However, the Marstrand biographer Karl Madsen points out that the developments which Marstrand hoped to awaken in Danish art were not the same that Høyen and the slightly younger group of artists, including Skovgaard, began to discuss during those same years. Marstrand wanted to improve the quality and professionalism of Danish art, while Høyen and his circle aimed to create a distinctively Danish mode of art that differed from the established one.31 Grasping this nuance is essential for understanding the paradox represented by Marstrand because it indicates that Marstrand’s national interest in the arts was primarily rooted in professional, skill-related concerns rather than political ones. This view is borne out by a frequently quoted letter to his friend and colleague Constantin Hansen (1804–80) sent from Rome in 1847 in which Marstrand clearly distances himself from Høyen’s ambition to create a distinctly national art associated with geopolitics:

What do all these ideas of politics, nationality and grain duties have to do with painterly impact and the beauty of lines? What does it mean that art should be national? Does this mean that it should be politically Danish, extending from the Kongeå to the North Sea, depicting only those subjects found therein? […] No, just as the self-same sun shines above the entire world, so is art without all bounds; it serves only Truth and Beauty. […] I shall not let myself be confused by these passing tales of Scandinavism, constitutions and such matters, for they have not one whit to do with the eternal laws of beauty, harmony and mankind’s urge to live in the realm of the dimly perceived. They may well be greatly important to us too as citizens, but not as artists.32

Here Marstrand very clearly states his belief that art and politics are separate entities that should not affect each other, but that of course the artist has a separate interest in both fields.33 The letter clearly refers to the manifesto issued in Høyen’s 1844 lecture. A few years later, in 1850, Flyveposten ran an attack against Høyen and his circle which closely echoes Marstrand’s words: ‘Nothing has less to do with nationality than art. The most glorious, widely sprawling realm is art’s only true native country’.34

In his letters to Skovgaard from 1854–55, Marstrand keeps his friend and colleague updated on the political situation in Denmark, but it is clear that his knowledge of constitutional affairs is perfunctory, remaining mostly at headline level, and he freely admits that he does not know much beyond what he reports in the letters.35 A striking contrast to the comprehensive political analyses found in the painter Constantin Hansen’s letters to Skovgaard during those same years. Even though a number of years have passed since Marstrand wrote his 1847 letter to Constantin Hansen, his interest focuses most keenly on matters that pertain more closely to his own professional field, art, and this includes Høyen’s conception of Danish and international art. Marstrand had little time for Høyen’s ideas about all the ills associated with German art. In a letter to Skovgaard from 1855 he comments that hopefully, the fact that severe winter weather had forced Høyen to stay in Berlin for the winter would improve his view of the German artists.36 Høyen’s nationalist animosity towards German art was also pointed out in Dagbladet’s article – and given that his sentiments were presumably based on both artistic and political differences, they were unlikely to be changed much by an involuntary winter encounter with German art. Yet despite their differences, Høyen and Marstrand were good colleagues, and Marstrand took part in the salons hosted in Høyen’s home, an important venue for discussing and developing art politics.

The portrait of Høyen

On the occasion of Høyen’s birthday, Marstrand painted his portrait in 1868 [fig. 2]. In a gesture of respect, Marstrand has depicted the art historian speaking about pictures by Raphael, shown behind him, and standing in front of open books that clearly signal Høyen’s academic qualifications. Strikingly, the portrait does not contain a single reference to Norse mythology or to national politics, aspects which were such a prominent part of Høyen’s endeavours. Marstrand has opted to completely remove Høyen from that context, perhaps because he believed that Høyen’s legacy was better served by an emphasis on his classic art historical achievements rather than on ‘passing tales of Scandinavism’.

Having been a professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts since 1848, Marstrand was appointed director of that institution from 1853 to 1857 and again from 1863 to 1873. Thus, he too held a prominent position of power from which to speak, and his close ties to the still predominantly conservative art academy should be particularly noted here. In the 1840s and 1850s, the nationally oriented artists struggled to gain seats in the Academy, causing some strife between the two wings. Not until Marstrand’s second term in office, which saw an adjustment to the membership rules so that prospective members no longer needed to be put forward by an existing member, did the previous preponderance of conservative forces on the academy shift and budge, making room for the (National) Liberal artists.37

By occupying a position on the outskirts of the progressive national agenda, and by explicitly keeping a certain distance from overtly political, agitational art, Marstrand got access to changing the systems from within. Yet in spite of Marstrand’s chance to wield organisational influence, Høyen was still the one who made the most noticeable imprint, certainly on art history as recorded by posterity – probably because he actively connected art and ideology by means of his powerful network, for example by arranging commissions and by managing the collecting activities of permanent collections.38

Art historian Gitte Valentiner has pointed out a paradox: that Marstrand appears to have been National and Cosmopolitan at the same time. In his relationships – such as in his position as regular portraitist to the National-Liberal Hage family – and presumably also in his personal political beliefs, Marstrand was in line with the other National artists, but he preferred not to incorporate this point of view in his artistic work.39 As has been demonstrated in the above, Marstrand’s letters clearly state that he wished to refrain from mixing art and politics, including what might be more narrowly considered ‘cultural politics’. The portrait of Høyen hints at the same position.

A national theme?

In 1853, Flyveposten levelled specific criticism at Marstrand, claiming that the Scandinavist subject matter of his painting Church-Goers Arriving by Boat at the Parish Church of Leksand on Siljan Lake, Sweden (1853) [fig. 3] pandered to Høyen’s national programme.40 Belonging to the Cosmopolitan camp itself, the newspaper might be right in claiming that Marstrand’s painting partly constituted an attempt to accommodate National tastes – after all, Høyen commissioned it for the Royal Picture Gallery.41 Marstrand did a large number of sketches for the painting, indicating great commitment. Despite this, it is worth considering whether the subject matter reflects Marstrand’s own ideas, or whether the work was, as claimed by Flyveposten, an overture to Høyen’s Scandinavian/ national agenda.

Marstrand’s subject is almost a one-to-one visualisation of Hans Christian Andersen’s (1805–1875) 1851 description of churchgoers going to Leksand.42 Right from the point of view adopted and all the way down to the breast-feeding infants, the silk-covered hymn books and the quantity of boats on the shore, the painting matches Andersen’s description.43

The most striking difference is that Marstrand has not decorated the ships with green branches or put red tassels on the men’s hats as in Andersen’s account. The very direct correspondence to the literary source may be interpreted as a calculated strategic effort to work with subject matter that would meet with Høyen’s approval. In light of Andersen’s text, however, one may also read Marstrand’s choice of subject as more apolitically illustrative than actively agitating. With this painting, Marstrand may not have been deeply immersed in Høyen’s agenda, instead seeking, as demonstrated by the Høyen portrait, to negotiate an intermediate position where the national or Scandinavian aspect is not the goal in itself, but instead a means toward resolving a commission.

All this notwithstanding, it is interesting to note the level of umbrage seemingly taken by Flyveposten at the mere fact that the painting complies with Høyen’s ideas and aspirations: the response tells us something about the unmet expectations the newspaper held of Marstrand. Fædrelandet, by contrast, praised the painting while also criticising the more Cosmopolitan artists David Monies (1812–94) and Elisabeth Jerichau Baumann (1819–81).44

The newspapers’ struggle regarding national aspects find clear expression in the discussion surrounding Church-Goers Arriving by Boat. The very fact that the Cosmopolitan Flyveposten is disappointed must mean that they had expected Marstrand to maintain a more apolitical position instead of engaging in what they perceived to be Scandinavian propaganda. The assessment of the works undertaken at the time is thus also a negotiation of the framework for the National category in which Dagbladet placed Marstrand in 1855: it is not the artists themselves who classify the works as National or not; those assignments are made in the art criticism published in the newspapers, and this is also where they conduct their internal struggles for setting the criteria for ‘the national’. If Marstrand was part of the National group, the criteria for National art (as established by Dagbladet) must necessarily also be able to accommodate the highly diverse paintings created by him and the six other artists in the group, providing good opportunities for negotiations between the various newspapers on the exact nature of the ‘National’ aspects – and for blaming each other for not living up to their own criteria in their art reviews.

Sociologist Athena S. Leoussi has argued that the history painting continued to play a significant role in the development of the many schools of national art emerging across Europe and that overall, artists developed a greater degree of historical sensitivity in the nineteenth century. Leoussi has demonstrated how a number of subjects spread out concurrently across canvases throughout Europe and across the different art schools, all of which laid claim to national individuality but actually adhered to transnational patterns. These included: the national, the nation’s history, the national portrait, the peasant as representative of the nation-state, and the ethnoscape of landscape.45

Such subjects were also widespread in Danish art during this period; they were precisely the circle of motifs that Høyen urged artists to cultivate. For Marstrand, his own art was to serve to strengthen Danish art in general, and the specific subject matter was not a crucial factor in this process; rather, the themes chosen were simply a medium for showcasing prowess and craftsmanship. By contrast, the choice of subject matter was a main concern for Høyen and his camp, because the right subjects could help evoke a sense of community. In a letter to his brother from 1846, Marstrand complained about struggling to sell his works because they did not depict traditional Danish folk scenes.46

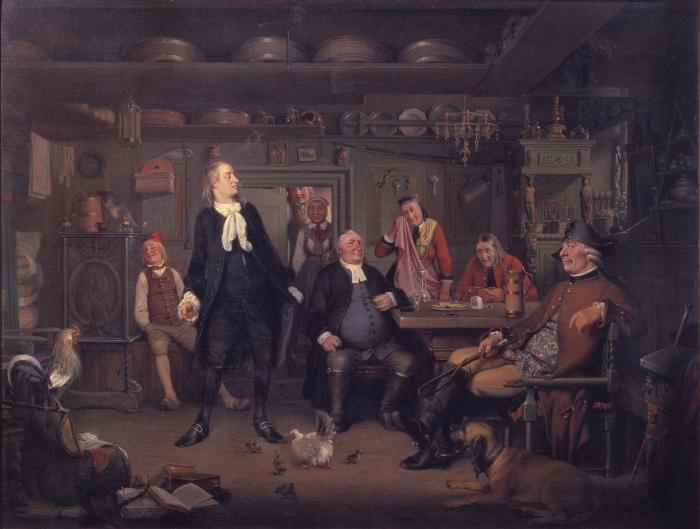

The so-called Holberg paintings become something of an escape hatch for Marstrand.47 For example, his composition From Ludvig Holberg’s ‘Erasmus Montanus’, Act III, scene 3 (1844) contains many of the same elements also found in other genre paintings from the period: plenty of peasants in regional costume and material embodiments of rustic, rural culture [fig. 4].48 In contrasts to the effect of authenticity sought in the other genre images, the Holberg scene has a clearly detached and slightly ironic quality due to the fact it depicts a piece of theatre, not reality. Here Marstrand was able to deliver scenes of folk life like Høyen wanted, but in a detached manner that allowed him to paint forth a narrative rather than an actual, real-life, paltry and unlovely peasant. In his Marstrand biography, Karl Madsen has stated that Marstrand begins to take a more mellow view of Høyen’s programme during the 1850s.49 If this is the case, his change of heart find no further expression in the subjects he chooses to exhibit: Marstrand generally sticks to his existing repertoire of portraits, Holberg scenes and Italian folk scenes in spite of his specific attempts to seek out new subject matter among Nordic landscapes, peasants and Norse mythology.50

This is to say that Marstrand’s choice of subject matter may be said to be national in feel, meaning that he represents many of the same trends also found in fellow artists such as P.C. Skovgaard – with the crucial caveat that Marstrand did not aim to politicise national aspects with his works.

P.C. Skovgaard as a visual political communicator

Unlike Marstrand, P.C. Skovgaard was among those artists who were happy to let politics influence their art. This assertion is based partly on the fact that he gave several of Høyen’s ideas and ambitions visual expression, and partly on his close affiliations members of the National Liberal movement.51 Høyen’s presence is quite often palpably felt in Skovgaard’s letters, either as a friend to be sent a greeting, as a travelling companion, or as an imagined critic of whatever Skovgaard was working on at the time.52

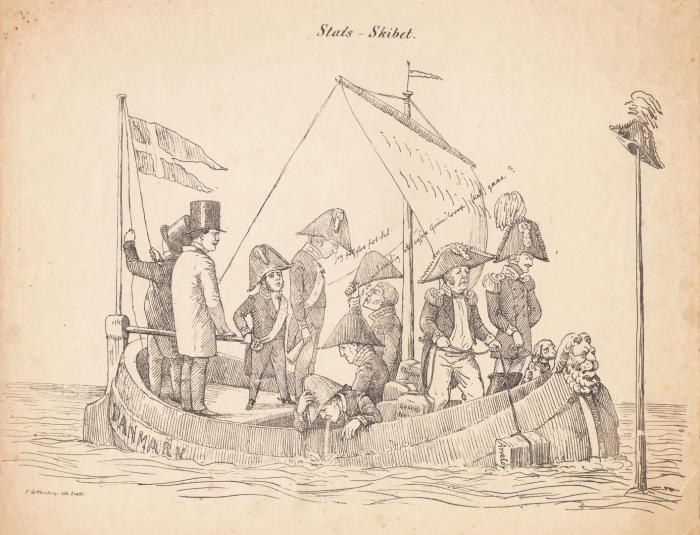

Skovgaard is not particularly explicitly political in his surviving letters to fellow artists, nor do they contain any comments on Dagbladet’s reports on the art world. Having said that, it should be added that all of Skovgaard’s surviving letters from the period 1854–55, the time when the discussion on art raged most fiercely in the Danish newspapers and when the Danish constitution was being challenged, were sent to family members, not to colleagues from the art scene.53 His political interests can be seen reflected in the letters Constantin Hansen and Marstrand sent to him while he was staying in Italy. For example, Marstrand comments on how the events back home in Denmark have apparently made Skovgaard uneasy, and later Marstrand even makes apologies for his somewhat brief update on the political situation of their native Denmark: ‘(…) Even though I know full well you are an avid politician and follow the events here at home, even when in Rome’.54 Overall, Skovgaard was kept regularly and well informed about the political situation back home during his 1854 trip.55 Skovgaard’s political leanings are further emphasised by a number of more explicitly political caricatures [fig. 5].56

Unlike Marstrand and Constantin Hansen, Skovgaard does not express his political views in writing; instead, he renders his (cultural) political views explicit in his visuals.

Landscape painting as history painting

It would seem natural to regard history painting (and folk scenes) as the genre of choice for a national edifying narrative, and indeed Marstrand and Constantin Hansen did work in this vein. But Skovgaard did not paint history paintings – certainly not in the traditional sense. Yet his landscapes often incorporate historical elements – not in the form of kings or mythological figures as in traditional history paintings, but in the form of various antiquities, medieval churches and the unspoiled Danish topography as Skovgaard imagined it, with magnificent beech forests and fading oaks.57 Skovgaard’s and J.Th. Lundbye’s (1818–48) joint trilogy of pictures created for H.C. Aggersborg (1812–95) in 1842 is regarded the most significant launching point of Skovgaard’s political depictions of nature. The paintings contain architectural references to Danish history such as a medieval church, the so-called ‘Goose Tower’ and Frederiksborg Castle, and the subjects chosen come across as potent sites of memory [fig. 6].58

The mid-nineteenth century saw a shift within the arts: landscape paintings began to dominate at the annual juried Charlottenborg exhibitions, outdoing e.g. history paintings in terms of numbers and popularity alike. In 1854, Dagbladet openly stated that they would refrain from reviewing landscape paintings that year in order to maintain a neutral position in the conflict between the Cosmopolitan and National artists.59 Their proclamation points to landscape painting as a prominent locus for negotiations on how the idea of national art should be interpreted and how one might recognise it among the artists. With his landscape paintings, Skovgaard was of course part of this negotiation and part of the movement that made landscape paintings popular. Based on this, I regard Skovgaard’s landscape paintings as a reinvented politicised extension of the history painting genre and as a visual expression of the political commitment absent from his letters.

Art historian Jane Gallen-Kallela-Sirén points out that the convergence of years of European revolutions, the growing focus on national identity and the rising popularity of landscape motifs is a logical consequence of the advent of national ideologies and their need to seize and occupy a territory by, among other things, constructing and highlighting it visually.60 Art historian W.J.T Mitchell defines such exercises of power as an imperialist performance capable of asserting control through a visualisation of the desired area – by designing symbolic ethnoscapes (to use a term coined by sociologist Athena S. Leoussi) to represent the nation.61 And because a territory is a political unit, a landscape painting is also always political according to Gallen-Kallela-Sirén.62 This new performative landscape tradition, of which I regard Skovgaard as a representative, also gained a firmer foothold in other parts of Scandinavia in the service of a range of different political intentions.63

Even though Skovgaard had been given the opportunity to travel to Italy in 1845, he initially opted to stay at home and travel around Denmark instead, supposedly at Høyen’s urging.64 This enabled him to study the variety found in the Danish landscape and to create some of his characteristic, monumental depictions of Danish beech forests65 [fig. 7] and the fascinating cliffs of Møn.66 On his journey through Denmark he did not simply reproduce whatever he happened to come across; rather, his paintings are carefully composed, deliberate constructs reflecting the national outlook on landscape and the world that he wanted to promote. The cliffs of Møn in particular, a geological manifestation of the deep roots of Danish history, are prominently featured in the selection of works he presented at Charlottenborg in the early 1850s: twenty-four out of twenty-five paintings depict Denmark; the last one is a scene from Venice. The ratio reflects the general trend in his total presentation of paintings at Charlottenborg.67 The conspicuous absence of Skovgaard’s Italian subjects at Charlottenborg indicates that they did not fit into the overall narrative he wanted to promote.68

Political portraits of a region

Art historians Karina Lykke Grand and Gertrud Oelsner have shown that the newly established and strengthened bourgeois elite often favoured site-specific subjects and that those who bought landscape paintings often lived very close to the geographical sites depicted.69 In this sense, landscape paintings were presumably not just a means of visualising and occupying the territory of the nation-state, but also of highlighting private property or the origins of individual families. Landscape paintings could serve to visualise power, property, memory and kinship for the bourgeois elite in the same way that classic history paintings traditionally served as instruments of power for monarchs and the aristocracy. A political portrait of a region, one might say. Skovgaard also took part in this regional and bourgeois exercise of power by painting the site of his own origins in Vejby in North Zealand, by painting the town Vejle for the leading National Liberal politician Orla Lehmann while he was a county governor there, and by painting the landscapes around the manor houses of Nysø and Iselingen, both favourite haunts of the National Liberals of the era.

In 1853, Skovgaard’s exhibits included Nysø on a Clear Autumn Day (1853) [fig. 8], which may perhaps be most accurately described as a portrait of the manor of Nysø (built 1671–73), which in the mid-nineteenth century formed the setting of many exchanges on art and culture. The sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844) spent a great deal of time here during the last years of his life. Thorvaldsen presumably worked in the yellow wing seen to the left in the picture when he was not staying in the pavilion on the other side of the main building. Nysø attracted a wide circle of national-minded artists who were well received by the lady of the manor, Christine Stampe (1797–1869), who was also the owner of this painting. Yet in spite of the long history of the building as the main seat of a barony, this is not an exalted, venerating portrait of the nobility and their possessions. The manor has an open, friendly air, forming a natural, down-to-earth part of everyday life with people (and livestock) from many different rungs of society. Busy women fetch water from the well, while a group of well-heeled citizens, some on foot, others on horseback, meet in conversation. The dog keeps an eye on the courtyard, the pigeons return home to their dovecote, and the goat is grazing. Everyone is going about their business without any fuss. Hence, this portrait of a manor house can be regarded as a kind of modern princely portrait, one in which Nysø embodies the newfound power of the bourgeoisie. In the past, art had been used to visualise the power of state and king by means of political portraits, and this portrait of a mansion serves as a kind of continuation of this tradition. While it does not depict a specific person in power, it can still be interpreted as a depiction of a specific political idea and a specific political circle of people associated with this particular place.

Skovgaard’s Danish landscapes and portraits of particular regions are, then, tangible expressions of a more nationalistic love of one’s nation, linked to a specific geography and history. By contrast, Marstrand did not regard genre scenes from Italy as incompatible with love of one’s nation: to his mind they were part of the efforts to become truly proficient within his field, allowing him to position himself among peers across national borders. Both Skovgaard and Marstrand were, then, fuelled by a national cause. Accordingly, the differences between these two artists may not be immediately striking, but it is important to understand that there were indeed differences between them. Being aware of this difference helps call attention to the variety – in terms of subject matter and political attitudes – that can be found among artists who have gradually been lumped together in one barrel. And it also helps to highlight the professional and political discussions which art took part in and contributed to in the mid-nineteenth century.

Conclusion

In 1854, Dagbladet proclaimed the existence of two cliques on the Danish art scene. The following year, the newspaper designed one of these cliques as National, the other as Cosmopolitan – and asserted that Marstrand and Skovgaard were both part of the National faction. Using Joep Leerssen’s theories of the cultivation of culture and transnational cultural centres, this article has examined how Marstrand and Skovgaard’s divergent perceptions of what constituted ‘national’ art were shaped and developed.

Even though the two artists were on the same page in many regards – both were interested in furthering national causes, and both were part of the same network – a closer analysis of their overall choices of subject matter, of their letters and their trips abroad reveals that they were not motivated by the exact same national cause. Skovgaard was part of a movement that wanted to actively use art to promote specific social developments, a movement led by art historian N.L. Høyen. Marstrand also wanted to work actively with art, but restricted these activities to specifically art-related issues, and he explicitly stated that he did not want to mix politics and art. Thus, the two colleagues did not completely disagree, but they had different goals.

The article also foregrounds how taking a critical look at the entrenched dichotomies of art historiography can unlock a better understanding of how artists collaborated, fought and evolved in their own time. And how revisiting the artists’ surviving letters gives us new opportunities for seeing the artists and their works as active participants in the social developments of their own day – developments which very much served as building blocks for the society we see today.