Summary

The article examines the significance of gender in the so-called Peasant Painter Feud which took place in 1907 in the Danish newspaper Politiken and has been widely used as a contextual reference for the period’s art. The article questions the reception of the debate in art historical literature and argues that the art created by the artists Agnes Slott-Møller, Bertha Dorph, Harald Slott-Møller and Gudmund Hentze was disqualified on the basis of gendered quality parameters. The article then goes on to use the Peasant Painter Feud as a lens in an examination of Agnes Slott-Møller’s works, seeing them as ‘micro-narratives’ that illustrate how Agnes Slott-Møller as a woman created her own space and scope for action, asserting her agency and inventing an original, eclectic idiom where a ‘female’ aesthetic played a central role in the unfolding of medieval subjects. In doing so, she deconstructed the gendered hierarchy of modes of expression set up by art critics in the Peasant Painter Feud.

Article

Over the course of three months in the spring and summer of 1907, readers of Politiken, a leading Danish newspaper, could follow a complicated debate involving a number of Danish artists. The debate has been named the ‘Bondemalerstriden’ – Peasant Painter Feud – in art history literature. Reaching its peak from April until July 1907, the dispute weaved itself into other ongoing debates about what kind of art Danish institutions such as the established exhibition at Charlottenborg, the artist association and venue Den Frie Udstilling, which was inspired by the French Salon des Refusés, and the national gallery, Statens Museum for Kunst, ought to show and acquire. In the summer of 1907, Politiken regularly ran articles and opinion pieces on the issue, sometimes several a day, and pieces in the cultural magazine Tilskueren can also be linked to the Peasant Painter Feud.1

In art history literature, the debate has often been used to point out two significant currents on the Danish art scene around the year 1900: one consisted of those who cultivated and supported a naturalistic painting style, the other comprised the Symbolist artists.2 The debate has been used to explain why Harald Slott-Møller and Agnes Slott-Møller in particular were subsequently assigned a marginalised position in Danish art history. Taking my point of departure in a feminist analysis of the discourse in articles written by Ernst Goldschmidt (1879–1959), Karl Madsen (1858–1938) and Agnes Slott-Møller (1862–1937), I will examine the significance of gender in the dispute and discuss the established reception of the Peasant Painter Feud.

By focusing on the significance of gender in this context, I aim to highlight how the Peasant Painter Feud favoured and exalted masculinity and argue that the debate and its subsequent reception form part of an institutional and discursive undermining of female artists. In doing so, I wish to deconstruct the established narrative asserting that the debate was factual and art-theoretical in nature, and question some of the parameters formerly used to explain the developments within Danish art history. The article thus also sets the stage for critical reflection on how to use and reproduce established narratives in art history.

Gendered disqualification

The Peasant Painter Feud took place during a period which saw a serious shift in how women artists were viewed in Denmark. Art historian Lennart Gottlieb has pointed out that up through the 1890s, the circle of members of Den Frie Udstilling changed; from having included a significant proportion of women artists, the association went on to systematically exclude them around the turn of the century. The artists’ communities Ung dansk Kunst (Young Danish Art) (1910–1912) and Grønningen, which emerged out of Den Frie Udstilling in 1915, included no women artists: ‘women were simply disregarded – or even despised – as artists’.3 In the PhD thesis Excentriske Slægtskaber (Eccentric Affinities), art historian Emilie Boe Bierlich investigates the dynamics responsible for women artists being written out of Danish art history, and this article builds on that work. In her thesis, Boe Bierlich examines how women artists who were popular in their own time were not represented at the institutions and excluded from art historical treatments of their period up through the twentieth century simply because they were women. She also argues that the art debate in Denmark around 1900 was defined by a gendered polarisation. In this article I argue that the Peasant Painter Feud is an example of this gender polarisation, but whereas Boe Bierlich focuses on the importance of being born female, I argue that the works of male artists were also dismissed and disqualified because critics saw their art as examples of ‘women’s art’. In doing so, I furthermore aim to add greater nuance to the discussion, expanding our understanding of the types of art that have been left out of art history, and to identify and describe some of the gendered parameters of exclusion that have also affected men.

Two different understandings of gender appear in the debate, which can be connected to a distinction between biological and social sex. The Peasant Painter Feud began with a defence of women artists where artists are grouped on the basis of their biological sex, while some critics associated the concepts of ‘women’s art’ and ‘manly’/‘masculine’ art with both sexes. The latter involves a social gender perspective associated with whether the art in question is seen as linked to something stereotypically female or male. When uncovering the gender hierarchies built up in the Peasant Painter Feud, it is useful to distinguish between biological sex and social gender, because such a distinction can shed light on how several of those involved in the dispute seem to think about gender.

In the book Gender Trouble, philosopher and queer theorist Judith Butler presents their4 understanding of the feminist project. Here they do away with a distinction between biological and social sex previously used in feminist theories to point out the oppression of women because it predetermines their identity.5 Instead, Butler deconstructs the meaning of gender and decentres the privileged position assigned to the masculine in meaning-making. They do this by exposing the exercise of power seen in discourses and in the practices of institutions.6 At the same time, they point out that there is in fact scope for action within the gendered production apparatus. Through the repetition of gendered codes, a change of identity can occur.7

Butler’s feminist queer thinking forms the theoretical starting point of this article, as I endeavour to expose the patriarchal discourses that have contributed to determining who became successful and who was relegated to an outsider position. In the analyses of Agnes Slott-Møller’s works, I examine how the works create meaning and cause shifts in the gendered hierarchies of representation.8 By this I mean that Agnes Slott-Møller did not accept gendered understandings of artistic idioms.

A perfidious debate

Art historians Bodil Busk Laursen and Susanne Thestrup Andersen are the ones who firmly inscribed the Peasant Painter Feud in Danish art history with the catalogue for the exhibition Kunsten og naturen (Art and Nature) from 1986. The two art historians use the dispute as a point of entry for looking at ‘forgotten currents on the art scene around the turn of the century’, motivated by ‘a renewed interest in the idea, form and style of images’.9 The exhibition presented some of the works mentioned in the articles and other pieces that formed part of the original debate. Their reception of the Peasant Painter Feud has greatly shaped recent art history’s view of it.10 In the catalogue from 1986, Busk Laursen and Thestrup Andersen describe the controversy as an artistic dispute: ‘At its core, the Peasant Painter Feud is a showdown between two different art movements: naturalism and Symbolism’.11 They further conclude that ‘the opposition, with its academic painting inspired by literature, lost the battle,’ with reference to the artists Agnes Slott-Møller, Harald Slott-Møller and Gudmund Hentze.12 The enduring resonance of Busk Laursen and Thestrup Andersen’s reading of the debate can be seen in the catalogue for the exhibition Agnes Slott-Møller – Heroes and Heroines from 2018, where art historian Iben Overgaard writes: ‘The discussion marked out fundamental differences between two prevailing art trends; Symbolism against naturalism, ideality against reality, spirit against nature’.13 And like Busk Laursen and Thestrup Andersen, Overgaard concludes that ‘Agnes and Harald Slott-Møller’s ideal ambitions for their art became relegated to a dead end’.14 Art historian Bente Scavenius also sees the debate as art theoretical in nature, presenting it as a dispute between ‘rustic “clog-wearing” art set against the refined and decorative art that Gudmund Hentze represented alongside the Slott-Møllers’. The literary historian Henrik Wivel, who authored the fifth volume of the major reference work Ny dansk kunsthistorie (New Danish Art History), points out that while the debate was initially gender political in scope, it took place on many levels, including the lowest, where ‘the artists lambasted each other with exquisite perfidy’.15 Wivel concludes: ‘at its core, the debate had to do with genre and style’.16 In the catalogue for the exhibition Mellem kunst og idealer (Between Art and Ideals) from 1988, which showed works by Agnes and Harald Slott-Møller and was also organised by Bodil Busk Laursen, she also points out political aspects to the ostracism of the two artists and concludes: ‘From then on, Agnes and Harald Slott-Møller were both regarded as belonging to the extreme right wing’.17 However, when reading the articles of the Peasant Painter Feud closely, it is difficult to synthesise the writers’ positions into two clear-cut art-theoretical or political positions the way the aforementioned art historians have done. The various writers’ agendas were informed by personal tastes and attitudes, power dynamics, misogyny and desperate attempts to defend themselves against other writers’ attacks in previous articles. It is therefore difficult to draw a clear picture of the two polar opposite positions of the Peasant Painter Feud. This is not only because more than a hundred years have passed since the debate took place. Hans Jæger’s (1854–1910) article ‘Malerkrigen – et resumé’ (The Painters’ War: A Summary) testifies to a certain amount of confusion at the time about the actual core of the dispute.18 As the Norwegian author stated:

Just as it was impossible for even the most attentive and interested reader to assert with clarity what the dispute was really about from these articles, it also proved equally impossible for the warring parties to make each other understand what each really meant.19

Rather than presenting the Peasant Painter Feud as a clash between two polar opposites representing two different art-theoretical directions, it may be more fruitful to see the debate as one comprising many different themes. Taking such a view, the discussion of different art movements constitutes one trajectory in the debate, while another is the notion that gender is connected with quality. A third approach might be to examine the meaning of ‘style’, a recurring theme in several of the articles.20 This is to say that the Peasant Painter Feud contains several narratives that can be unpacked, depending on how the sources are selected and delimited.

The participants in the Peasant Painter Feud

In order to understand the nuances of the debate, it is important to form an overview of who actively took part in it. The articles featured in the publication Naturen og kunsten (Nature and Art) had been found in a folder labelled ‘Peter Hansen’ in Hjalmar Bruhn’s collection of clippings at the Royal Danish Library. Thus, the starting point for the publication was source material selected as relevant to the artist Peter Hansen (1868–1928), who was also active in the debate. The authors write: ‘In the exhibition catalogue, the parties in the dispute get to speak for themselves. The most important entries are printed in full’.21 Today, Politiken’s archive has been digitised and made available on the newspaper’s website, and if, for example, you search for ‘Slott-Møller’, it is possible to find more entries in the discussion than those featured in the catalogue. In what follows, I will focus on articles that are particularly relevant to Agnes Slott-Møller and which touch on the significance of gender.

Gudmund Hentze (1875–1948) launched the Peasant Painter Feud with an opinion piece headlined ‘Dansk Foraar’, meaning ‘Danish Spring’, which was published in Politiken on 14 April 1907. Taking a confrontational tone, he criticised ‘the lumped-up coterie of Peasant Painters’, which he believed had too much power. He was referring to the Funen school of painters, which included Fritz Syberg (1862–1939), Peter Hansen and Johannes Larsen (1867–1961).22 Hentze was prompted to write the piece by a specific event: the jury of the Charlottenborg exhibition had rejected Gerda Wegener’s (1886–1940) Portrait of Ellen von Kohl, 1906.23 In his defence of Wegener and the rejected work, he also mentioned three other artists whom he believed were overlooked and underrated on the Danish art scene: Agnes Slott-Møller, Bertha Dorph (1875–1960) and Juliette Willumsen (1863–1949). In the article, Hentze drew a picture of a cliquey art scene where a single, particular view of art dictated what should be exhibited at Charlottenborg and Den Frie Udstilling, leaving no room for what he, pointing to Wegener’s portrait, called ‘a sign of a new spring in Danish art’. Siding with Gudmund Hentze, Agnes Slott-Møller joined the fray, and they were later joined by her husband, artist Harald Slott-Møller (1864–1937).

The Funen Painters only contributed a brief piece to the debate, written by Peter Hansen, but Ernst Goldschmidt and Karl Madsen both came to their defence. Karl Madsen, who originally trained as an artist, became a member of the gallery commission at Statens Museum for Kunst in 1899. He went on to become a curator there in 1900 and was eventually appointed director in 1911.24 Madsen became involved in the debate after Hentze – in an article on ‘Nature and Art’, also published in Politiken – had criticised the acquisition policy at Statens Museum for Kunst.25 Following this, Madsen became one of the most active contributors to the debate.26 Ernst Goldschmidt was an artist and published the magazine Det ny Kunstblad (The New Art Journal) in 1910–11. He also wrote for Politiken and was a regular reviewer for the newspaper from time to time.27

A gendered hierarchy

Gudmund Hentze does not explicitly mention gender as the reason why the named women artists were overlooked at that year’s exhibitions. However, if one looks at how women artists were described in discussions at the time – and specifically in the Peasant Painter Feud – it becomes painfully clear that their gender stood in the way of any real recognition of their work. In Ernst Goldschmidt’s article ‘Charlottenborg-Udstillingen IV’, gender plays a significant role. He begins by explaining what the dispute is about:

The controversy, which one party in particular now seeks to stir up, is not about a struggle between drawing and colour, nor between a striving for beauty and the worship of nature – for they cannot be separated – but a struggle between authenticity and affectation. And those who are not partisans in the service of art-political purposes will easily be able to see that Mrs Slott-Møller’s Young Danish Nobles exhibited this year pales and becomes dry, toneless and contrived when seen next to Joakim Skovgaard’s scenes on similar themes, and that [Harald] Slott-Møller’s portraits become empty and superficial exercises of form when juxtaposed with Ejnar Nielsen’s deep, lovely monumentality. Skovgaard and Nielsen are artists who favour drawing and line as much as anyone, so this is not about a dispute between different artistic principles, but a matter of assessing quality.28

In Goldschmidt’s view, the dispute was between two groups of artists, one representing ‘authenticity’ and the other ‘affectation’.29 A Danish dictionary from 1919 states that affectation is associated with a certain ‘unnaturalness in one’s being’ and ‘the addition of self-deception’.30 Goldschmidt associated the same qualities with what he called ‘women’s art’. He used this term in a description of the painting Hos den unge Barselskvinde (Young Woman in her Confinement), 1907, by Bertha Dorph, one of the four women artists defended by Hentze:

There is a gossamer quality akin to the lightness of kiting spiderlings to Mrs Dorph’s picture, something cheerfully festive, something instantly endearing, a smiling feel about her figures. They are clearly aware that they are beautiful, but then it is such a strongly feminine trait to want to please, to want to look good, to want to show off a little beauty spot in a smiling face, as long as it is becoming, even if it is not one’s own. And Mrs Dorph’s large picture is undoubtedly the most typical piece of women’s art painted in Denmark.31

In the quote, Goldschmidt establishes a connection between the embellished (the beauty spot), the feminine, and the unoriginal (the falsity of the beauty spot) and concludes that this type of art, which he also described as the ‘nineties quest for style’, had lost out. In the article he makes a clear distinction between good original art and artificial and unoriginal art, eventually concluding that the winner is neo-naturalism:

The spirits who have stood guard over Danish art have wanted things to be so that the nineties’ quest for style did not became decisive for its future. Side by side with it, a New Naturalism grew forth, heavier and broader than that of the eighties [1880s], and at the same time a young art which, conveyed through strong and independent personalities, united a deep striving for simplicity with a sense of colour and a cultivation of painterly aspects.32

Ernst Goldschmidt worked with various dichotomies between the real and the fake, the young and the old and the good and the bad. Positioned opposite genuine art one finds an inauthentic and empty art that cannot decide on a mode of expression, and which he associates with women’s art. He thus sets up an ideal of ‘real’ art and defines women’s art as ‘other’.33

Ernst Goldschmidt would come to play a part in the development of Danish modern art. In his dual roles as artist and reviewer, Goldschmidt preferred artists who could ‘see and feel for themselves, and incorporate in their art the colouristic devices that the new age has brought them,’ as he states in a later article.34 Goldschmidt used the terms ‘young art’ and ‘modern art’ to describe the neo-naturalism which to him constituted the new viable art of the time. Goldschmidt had various platforms from which to disseminate his view of art and women. He was editor of Det ny Kunstblad, described by art historian Villads Villadsen as ‘the mouthpiece of the young generation’ in his book about Statens Museum for Kunst.35 As a member of Ung dansk Kunst from 1910 to 1912, he exhibited alongside fellow artists such as Harald Giersing (1881–1927) and Sigurd Swane (1879–1973) in 1910, and he was part of the circle of artists who founded Grønningen in 1915, a group which would constitute an important community for the development of Danish modernism. The rules governing who could exhibit in these associations reflected the view of art presented by Goldschmidt in the Peasant Painter Feud. For example, only men could become members of the association Ung Dansk Kunst at Den Frie,36 and, as was previously mentioned, the artist association Grønningen left out women artists.37 Thus, women were denied access to several of the communities that would play a central role in the development of Danish modernism.

Interestingly, Goldschmidt not only used the traits he associated with women’s art to criticise Bertha Dorph’s work; he levelled the same criticism at Harald Slott-Møller’s portraits, which he saw as ‘empty exercises in form’. He also associated Gudmund Hentze’s representations of the medieval ballad about Germand Gladensvend (Germand the Merry)38 with women’s art, using the ballad as an image of the 1890s search for style and making a connection between the song’s story about Germand, who borrows his mother’s magical feathered cloak, and affected art.39 Through such tangled, indirect juxtapositions and associations, Goldschmidt conveyed that not only the women in Bertha Dorph’s work adorned themselves with borrowed feathers; so too did male artists such as Gudmund Hentze and Harald Slott-Møller. Thus Goldschmidt attributed ‘female’ characteristics to the art created by these two male artists, which in his view disqualified them.

Unimaginative women artists

Goldschmidt has not been prominently featured in art history’s treatment of the period. Lennart Gottlieb describes him as a bad artist, but perhaps Goldschmidt’s art historical significance does not reside in his role as an artist, but rather as a figure of power within the fields of art criticism and on the art scene. He was supported, among others, by Fritz Syberg, who praised him for one of the opinion pieces that formed part of the Peasant Painter Feud. In an undated letter, Syberg wrote: ‘Next, I would very much like to thank you for your beautiful opinion piece, which has pleased me for reasons that I can better talk about than write about’.40 Goldschmidt remained popular, and when Statens Museum for Kunst was to have a new director in 1930, the association ‘Malende Kunstneres samfund’ (‘Society of Painting Artists’) chose Ernst Goldschmidt as their candidate for the position.41

When seeking to understand the Peasant Painter Feud, Goldschmidt’s contribution is interesting because it makes explicit a sexist tone in the general art debate, and he is an advocate of the kind of modern art which would dominate art history’s treatment of the first half of the twentieth century.

In an article, Harald Slott-Møller describes Ernst Goldschmidt as Karl Madsen’s ‘fellow combatant’,42 and indeed there are parallels between Goldschmidt’s and Madsen’s outlooks on art. Like Goldschmidt, Madsen wrote that the debate is about the authentic versus the inauthentic: ‘The fight to ensure that no genuine values, whatever they may be, are rejected and disregarded in favour of false values, even if they cover themselves up in beautiful names’.43 Karl Madsen also believed that the debate was essentially about quality or what he called ‘good’ and ‘bad’ style. The artists highlighted by Madsen as particularly skilled were all men, while he consistently criticised the women artists: Madsen wrote that the air emanating from Elizabeth Jerichau Baumann was thin, and according to Madsen it was a surprising and gratifying step forward for Bertha Dorph when she officially gave up her efforts to do what he describes as ‘taking on a style’:

Mrs Bertha Dorph has publicly declared that, at the instigation of her husband, her picture exhibited this year sees her to turning her back on [the efforts to take on a style]. It is clear that in doing so, she has made great and gratifying progress, which her great energy and skill will doubtless permit her to continue’.44

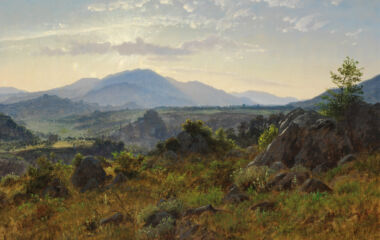

The message conveyed here is that she had not succeeded in defining her pictures by means of ‘style’, and that abandoning this approach to art was a positive step. A trait common to several of Madsen’s mentions of women artists was that he would initially praise them in a patronising manner and then proceed to judge their works. Madsen’s description of Agnes Slott-Møller is no exception. He writes that the artist’s choice of subject matter might well be fine, but the execution was poor, adding that ‘the general public regards her as excellent’.45 In a later opinion piece he made his position clear when, directing his comments at Agnes Slott-Møller, he wrote that ‘too many fritter away their energy on small tasks. Colouring in dolls in knights’ costumes is a woefully small undertaking’.46 Madsen did not specifically mention the gender of the artists involved in the Peasant Painter Feud, but his comments on the women artists were negative. At the time of the debate he was a curator at Statens Museum for Kunst and a member of the gallery commission in charge of deciding which works the museum should acquire. In his previous role as a critic, he would use gendered parameters of quality on several occasions. In a review of the opening exhibition at the Den Frie Udstilling in 1891, he praised Agnes Slott-Møller’s Queen Margrete I, Eric of Pomerania and the Jutlandic Aristocracy, 1889 [Fig. 1]. He concluded by stating: ‘The picture in no way reveals that it came from the hand and mind of a woman’.47 This is to say that Karl Madsen could be positive towards works made by female artists – as in this review of Agnes Slott-Møller’s work – but in his assessment of artists, he, like Ernst Goldschmidt, applied gendered understandings of what was good and bad. The starting point was that women’s art was unimaginative and fundamentally less interesting than men’s art.48 A similar example can be observed in his review of Susette Holten’s works from 1888, where he used the words ‘manly boldness’ to describe good works and ‘the hallmarks of women’s work’ as a contrast to this:

If one did not know any better, one would never guess that ‘The Troll Sucking the Lake Dry’ and ‘The Dragon Guarding the Entrance to the Mountain’ were the work of a lady, Miss S.C. Skovgaard. They are characterised by a rather manly boldness, very far removed from the gentle prettiness considered the hallmark of women’s work; the imagination from which they spring does not seem to strive for ‘the beautiful’.49

Male critics were not alone in reproducing such stereotypical perceptions of art made by women – the general polarisation of the genders and widespread understanding of art as a male space was so embedded in the social debate that female critics also reiterated gendered stereotypes in the media, favouring men.50

Peter Hansen, who contributed a short entry in the Peasant Painter Feud, did not mention anything about gender in his piece. However, he actively contributed to the exclusion of women artists from art history when, as the artist behind the painting The Inauguration of Faaborg Museum, painted in 1910-12, he ensured that Alhed Larsen, Christine Swane and his own sister Anna Syberg were not included in the large group portrait of the Funen Painters.51 The exhibition Peter Hansen. I Paint What I See in 2022 at Ordrupgaard sparked a debate about Peter Hansen’s view of women, prompting the museum’s director, Anne Birgitte Fonsmark, to make the following comment: ‘In those days, Hansen’s view [of female colleagues] was not “unusual”. On the contrary, it was the norm, a fact well known to those interested in history’.52 The entries from Karl Madsen and Ernst Goldschmidt support Fonsmark’s point, while Gudmund Hentze’s contributions show that there were indeed male artists who took up women’s issues in the media. This is to say that not all male artists dismissed and disqualified the female artists, and men also had the opportunity to contradict this ‘norm’.

Challenging patriarchal structures

Despite the similarities between Madsen’s and Goldschmidt’s assessments and arguments on what constitutes good and bad art, they had slightly different perspectives on what was the ‘right’ kind of art. Madsen was an advocate of naturalism and a major guiding light for artists and audiences alike, but by 1907 he was no longer orientated towards new currents. The Norwegian art historian Jens Thiis writes that Madsen grew ‘tired of the ceaseless criticism of alternating modern currents’, turning to older art instead.53 In this respect, Goldschmidt held a different position, being a younger art critic and an advocate of the various associations that sprang from Den Frie Udstilling. He later protested that Statens Museum for Kunst mostly bought works by dead and older artists.54 Despite their differences, the two art critics shared a view of art rooted in French naturalistic painting.

Goldschmidt and Madsen’s perception of art made by women artists parallels the kind of devaluation described by feminist art historian Marsha Meskimmon in her treatment of the Weimar Republic’s view of female artists in the period 1918 to 1933.55 Focusing on a German context, she examines how the general understanding of the modern was used to exclude artists in the same way that Goldschmidt’s understanding of ‘young’ art was also used to exclude women.

Meskimmon challenges the written art history that has become accepted as the ‘right’ one. In her book We Weren’t Modern Enough she rearticulates the contexts surrounding specific works by women artists. Rather than focusing on the women’s limitations, she examines the female artists’ scope for action, ‘how’ the works mean something, and how female artists used different female typologies as a collection of ideas they could apply in different contexts, thereby countering the central position held by the masculine subject:56

Far from demonstrating a single, unified aesthetic in relation to ‘woman’, women artists were able to appropriate, manipulate and challenge monolithic stereotypes of woman as other, definable only in relation to a masculine subject, and in doing so, they questioned the centrality of the masculine subject and the canonical constructions of art and history premised upon the marginalization of woman/women.57

Meskimmon uses the concept of ‘micro-narratives’ in order to allow marginal subjects scope for action. By highlighting selected examples, she sets out to challenge the canonised understanding of art history:

Choosing to focus upon a limited number of works and privileging the textual sources written by, and/or directed towards, women produce a forceful archaeology of an alternative viewpoint meant to shift our perception of the landscape of Weimar culture.58

Taking my point of departure in Meskimmon’s focus on female artists’ agency, emphasising their scope for action rather than the oppressive structures around them, I will go on examine how Agnes Slott-Møller resisted the male critics’ notions about the ‘female’.

First, I will examine Agnes Slott-Møller’s contributions to the Peasant Painter Feud, then explore an example of the communities of which she was part, and finally consider how she visually appropriated and manipulated idioms that had become associated with the feminine.

Counternarratives

Agnes Slott-Møller used different platforms and mouthpieces to make her views known. For example, she published two books: Nationale Værdier (National Values), 1917, and Folkevisebilleder (Folk Ballad Images), 1923, and she wrote articles in Politiken. In connection with the Peasant Painter Feud, her article ‘Kunsten og Emnerne’ (Art and Its Subjects) was part of the debate. Here she focused not on gender, but on the content of art and what it should be, pointing back to Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement from 1536–41. For Agnes Slott-Møller, the Peasant Painter Feud was a clash between painters who favoured different types of subject matter: modest or grand.

I don’t know why it is considered so healthy, especially among a people like the Danish, to always warn against the grand subjects. When art was at its best, it did indeed dealt with the greatest, weightiest of subjects even though it was not equipped to do so at all. Many a work of ancient and old art touches us precisely because of its inherent contrast between a full heart and a halting, stuttering voice.59

In writing these words, she went up against a Danish tradition which favoured everyday subject matter in art. Subjects of the kind that Peter Hansen, Johannes Larsen and Fritz Syberg, but also Vilhelm Hammershøi, depicted in their paintings. She defended her art against Karl Madsen’s labelling which proclaimed her a painter for the ‘general public’, emphasising that her audience included poets, artists, scientists and art critics – in other words:

People who possess the highest degree of education and refinement found in our times, but regrettably for me not people with the financial wherewithal to buy paintings and thereby give me the material support that the Heavens above and Mr Karl Madsen both seem to feel that I should forever do without.60

Perhaps Agnes Slott-Møller did not mention her position as a woman artist because this would, within the gendered hierarchy of the time, be tantamount to automatically disqualifying herself. Instead, she proved her support among the intellectual elite the following year when thirteen leading figures in the realm of Danish culture approached the Gallery Commission at Statens Museum for Kunst, requesting the museum to acquire her work Elverhøj (Elves’ Hill) from 1906 – the very work which the jury at the Charlottenborg exhibition had rejected in 1907 and which was part of the reason why Hentze wrote the piece on a ‘Danish spring’, launching the feud. The signatories included the critic and literary scholar Georg Brandes (1842–1927), the painter Peder Severin Krøyer (1851–1909), who had taught Agnes Slott-Møller, the writer Valdemar Vedel (1865–1942), the professor of Danish literary history Vilhelm Andersen (1864–1953 ), the philosopher Harald Høffding (1843–1931) and the architect Martin Nyrop (1849–1921). The letter from these illustrious and erudite gentlemen was printed in Politiken, causing the debate about Agnes Slott-Møller’s art to flare up again in 1908.61

Claiming agency through decorative painting

Agnes Slott-Møller resisted the exclusion of women artists in the public debate in various ways. She fought to be represented in museum collections and received support on this matter from other women who had a voice in the contemporary debates about women’s rights.62 Thus, she challenged the gendered hierarchies that were part of the general discussion on art. This process of negotiation can also be observed in her works, which incorporate decorative and naturalistic idioms alike.

Literary historian Pil Dahlerup has described Agnes Slott-Møller’s works as a postmodernist stylistic mixture of naturalism, historicism, heroism and national consciousness with tendencies towards ‘patriotism and symbolism’.63 Here, the term ‘naturalism’ should be understood in the sense proposed by Georg Brandes: a distancing from the supernatural and an acknowledgement of the necessity to ‘paint everything after nature’. Dahlerup writes: ‘Light, air and plein air painting are precisely the ingredients that Agnes Slott-Møller used to paint her manor houses and landscapes’ and concludes that Agnes Slott-Møller was a naturalist in her renderings of buildings and landscapes.64 Seen in the light of the Peasant Painter Feud, it is interesting that Dahlerup regards Agnes Slott-Møller as a naturalist given that Agnes Slott-Møller is unfavourably contrasted up against naturalism in the debate. This holds true of Goldschmidt’s and Madsen’s articles alike.

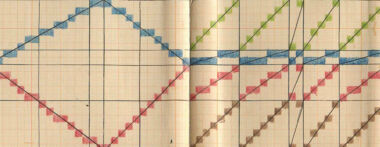

As Dahlerup writes, Slott-Møller’s works are characterised by a certain eclecticism. However, Dahlerup does not mention the role of the decorative in the artist’s works. Several women artists of the period worked within the decorative field, partly because the artistic training available to women until 1888 in Denmark was primarily offered at the Tegne- og Kunstindustriskolen for Kvinder (The School for Drawing and Decorative Art for Women) – a school aimed at training women to take on jobs at companies specialising in applied art. In their book Old Mistresses (republished in 2013), art historians Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker describe how the decorative has become associated with the feminine in art history writing. In the preface from 2013 Pollock writes: ‘the decorative arts were seen as a whole as feminized in […] negatively valued terms: using patterns, derivative, repetitive, above all unoriginal’.65 For the same reason, decorative arts have also held lower status than painting and sculpture, which were considered to belong to the domain of art, while decorative arts have been viewed as embellishments, unnecessary fripperies.66 However, Slott-Møller sought to effect a shift in this perception of the status of the decorative through her works.

While Slott-Møller focused mainly on painting, she would often also design her own picture frames and let them be part of the work. One example is the work The Dying Betrothed, 1906 [Fig. 2], where the titular character, Master Oluf, is shown lying in a large bed with a multitude of embroidered pillows, cushions and fabrics with different patterns. The winding patterns of the frame enter into a visual dialogue with the ornamentation on the bed with the seeming effect of pulling the bed into the space occupied by the viewer. Oluf’s fiancée is depicted wearing a blue-green dress ornamented with leaves, and between them is a large chest of jewellery. In the detailed depiction of patterned fabrics and elaborate furniture, Agnes Slott-Møller cultivated the decorative idiom associated with the feminine. But she also shifted the status held by the decorative. She did this by letting decorative elements form part of the painting’s overall representation, giving it emphasis and by letting the decorated objects carry the story of the work forward instead of being merely for decoration. In the medieval ballad about the dying betrothed, the maiden says goodbye to him and receives a box of jewellery from him. This angers his mother, meaning that the box of jewellery serves an important narrative function in the ballad and painting alike. Slott-Møller’s work thus establishes a connection between the decorative elements and the subject matter of the artwork, and furthermore the decorative arts are present both on a representative level within the painting and on a very concrete level in the frame. Harald Slott-Møller and the artist J.F. Willumsen also worked actively with the frame as part of the overall expression of their works in the 1890s. Art historian Jacob Thage emphasises that Harald Slott-Møller’s frames were less actively incorporated into the works, being more of a harmonising element.67 In Willumsen’s Jotunheim, 1892–93, the frame supplements the painting’s subject matter in terms of content, and a kinship can be observed here between Willumsen and Slott-Møller’s inclusion and activation of the decorative in their paintings. This is to say that several artists were interested in the overlap between applied arts and art in the 1890s, transcending the gendered hierarchies between the decorative arts, generally associated with women, and painting, which was dominated by men. Agnes Slott-Møller is among the artists who upheld the decorative in her works, continuing to do so until the 1930s.

Slott-Møller’s landscapes are often naturalistic, as can be seen in works such as Master Oluf, 1895 [Fig. 3], which shows a scene from a medieval ballad about Master Oluf waiting for his bride to arrive at his home. Master Oluf, marked for death after having danced with the elves, looks out across a summery landscape. At the top of the picture is a frieze executed in a medieval, decorative style with gold leaf and flowers as recurring elements, its centre showing a woman clad in white arriving on horseback. A sketch in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art shows that this part of the work was one of the first elements envisioned by Slott-Møller.68 The decorative frieze is where the bride is seen riding towards Master Oluf, thus setting up the central premise of the narrative.

At the early and late stages of her career, Agnes Slott-Møller practiced history painting, which for almost a century was considered the noblest and most exalted discipline at the art academy. Thus, the genre had been cultivated by the greatest male artists of the time. Artists had to master history painting in order to earn the academy’s gold medal and obtain the privileges that came with it. By executing the monumental work Niels Ebbesen, 1893–94, representing one of the heroic figures of the Middle Ages, Slott-Møller thus entered into a strong tradition from which women artists had been excluded.69 In a series of works from 1930–34 depicting scenes from the life of Valdemar II, also known as Valdemar the Victorious, Agnes Slott-Møller returned to history painting and used a distinctly decorative style. In these works, the ornaments and winding shapes of the frames almost overpower the subject of the painting, giving the frame and canvas equal status in an accelerated decorative idiom. In King Valdemar’s Wedding to Queen Dagmar, 1932 [Fig. 4], Slott-Møller has also included a naturalistic landscape in the decoration of the frame.

In these works, Agnes Slott-Møller uses ornament and the decorative in a new way, actively using these elements to unfold the medieval tales while the naturalistic landscapes act as a backdrop. The decorative elements are not passive, not merely something to please a viewer. On the contrary: in several cases the cause of the conflict or drama resides in the decorative elements. By emphasising the decorative in her works in different ways, she raised the ornament out of the passive status hitherto ascribed to it in art history, and Slott-Møller thereby undermined a patriarchal understanding of what ‘women’s art’ was. Through the appropriation of a typical female mode of expression, she created an original space of expression which she persistently explored and developed throughout her career. In doing so, she broke away from Ernst Goldschmidt’s hierarchy of representation where the embellished and decorative was seen as passive, subordinate to the independent naturalism.

Rethinking the Peasant Painter Feud

In art historical literature, the Peasant Painter Feud has been used to explore and explain which artists became part of Danish art history and which were relegated to its margins. The artists Agnes Slott-Møller, Harald Slott-Møller and Gudmund Hentze have been labelled as the losers in the debate, thereby supporting a narrative about the victory of the Funen Painters Peter Hansen, Johannes Larsen and Fritz Syberg.70 However, the Funen Painters prevailed on the basis of a perception of gender we question today. The museums have revised their acquisition policies, and we now want to include women artists in our understanding of the period. We cannot exclude works of art from collections on the basis that they were made by women artists or that the works are regarded as women’s art in a negative sense.71 While more equal representation of the biological sexes in museum collections is an important goal, another objective might be to reconsider which views of art we have winnowed out along the way, and whether a greater openness towards the artistic idioms and materials we address in our art historical studies might make for a more inclusive look at the art of the period, one that also extends to male artists who have been excluded due to a gendered view of art.

An awareness of gender-based dismissal and disqualification of artists can be used to revisit our understanding of the art of the period and decentre the position held by naturalism and modernism – two movements which provide several examples of artist communities excluding women. Rather than seeing the Peasant Painter Feud as beginning of the end of Agnes Slott-Møller’s artistic career, I have used it as a lens for examining her eclectic approach – a mode of expression where she negotiates a dual decorative and naturalistic idiom and breaks down the hierarches set out by Ernst Goldschmidt and Karl Madsen for contemporary art. In doing so, I see her works as micro-narratives about how women artists created scope for action for themselves in an art world defined by masculine values. Appreciating Agnes Slott-Møller’s eclectic idiom requires a less dogmatic approach to the art of the period and is associated with the postmodern gaze also applied by Pil Dahlerup to Agnes Slott-Møller’s practice. Slott-Møller created an original visual mode of expression that incorporated decorative strategies in her canvases and frames alike, commenting on the aesthetic paradigms of her day. She thereby challenged the established narrative asserting the existence of a distinctive type of ‘women’s art’ with particular characteristics.

If we continue to regard and reiterate the Peasant Painter Feud as a factual art theoretical debate, we legitimise Goldschmidt’s and Madsen’s misogynistic discourse where quality was linked to gender and women’s art was synonymous with all things hollow, empty and unoriginal. Perhaps we need to look elsewhere when contextualising the art of the period. This is certainly the case when dealing with Agnes Slott-Møller, Harald Slott-Møller, Bertha Dorph and Gudmund Hentze: doing so will enable us to place them within more fruitful contexts and appreciate their importance and impact on Danish art and culture.

Peasant Painter Feud articles/opinion pieces:

Gudmund Hentze: ‘Dansk Foraar’, Politiken, 14.4.1907

Peter Hansen: ‘Foraar’, Politiken, 21.4.1907

Gudmund Hentze: ‘Natur og Kunst’, Politiken, 26.4.1907

Karl Madsen: ‘Kunst og Natur’, Politiken, 3.5.1907

Gudmund Hentze: ‘Kunst og Kritik’, Politiken, 4.5.1907

Ernst Goldschmidt: ‘Charlottenborg-Udstillingen IV’, Politiken, 5.5.1907

Agnes Slott-Møller: ‘Kunsten og Emnerne’, Politiken, 6.5.1907

Gudmund Hentze: ‘Stakkels Peter’, Politiken, 7.5.1907

Harald Slott-Møller: ‘Karl Madsen’, Politiken, 8.5.1907

Ernst Goldschmidt: ‘Harald Slott-Møller og den moderne Kunst’, Politiken, 12.5.1907

Karl Madsen: ‘Kunst og Kritik’, Politiken, 12.5.1907

Karl Madsen: ‘Kunsten og Emnerne’, Politiken, 14.5.1907

Harald Slott-Møller: ‘Madsens Polemik’, Politiken, 16.5.1907

Karl Madsen: ‘Bondefanger-Kritik’, Politiken, 18.5.1907

Harald Slott-Møller: ‘Afslutning’, Politiken, 19.5.1907

Karl Madsen: ‘Et farvel’, Politiken, 22.5.1907

Gudmund Hentze: ‘Afslutning’, Politiken, 24.5.1907

Ernst Goldschmidt: ‘Charlottenborg-Udstillingen (Sidste)’, Politiken, 25.5.1907

Hans Jæger: ‘Malerkrigen. Et Resumé’, Politiken, 12.6.1907

Gudmund Hentze: ‘Malerkrigen’, Politiken, 1.7.1907

Hans Jæger: ‘Malerkrigen endnu en Gang’, Politiken, 9.7.1907

Harald Slott-Møller: ‘Kunstbetragtninger i Anledning af Udstillingerne 1907’, Tilskueren, 1907