Summary

Knud Pedersen’s projects do not restrict themselves to being based on a single idea and striving to realise that idea. Instead of working in a focused, target-specific manner towards a predetermined result, he allowed every step along the way to give rise to new ideas and projects. The form of his work is equally difficult to pin down: Sometimes his projects can be described as art or as art mediation, in other cases they take the form of an invention or a kind of entrepreneurial activity. This article will use a detailed review of a single project, Systembolaget/Auktion og Flaskepost (Systembolaget/Auction and Message in a Bottle) (1974–76), to outline how his work can be described as innovation without defining itself in terms of a single, easily classifiable work form or working method.

Article

Thanks to Knud Pedersen, the stores at the National Gallery of Denmark include a 1970s information poster issued by Systembolaget, the Swedish chain of government-owned stores that hold a monopoly on all off-licence sales of alcohol in Sweden.1 [fig. 1] The poster says “Spola kröken”. A sample study conducted by Pedersen himself demonstrates that most Danes do not know what this Swedish phrase means. Empty the bottle, perhaps? No, “wipe the slate clean” would be nearer the mark.

Pedersen’s work with information materials issued by Systembolaget was initially prompted by a fascination with slogans such as these, but ended up as something else entirely. One of the highlights of this work was an event held on the beach at Kronborg in Elsinore on 11 September 1976, involving an auction of Systembolaget posters conducted by artist Eric Andersen and the sending of messages in bottles to Systembolaget, but perhaps the preliminary work that preceded this event and the texts that followed should also be regarded as part of the project. Explaining the poster’s presence in an art museum by means of concepts such as ‘art’, ‘artist’ and ‘art mediation’ is to consign everything apart from the event itself to the margins. By contrast, endeavouring to see all the activities and documents associated with the event as a ‘work of art’ is to expand the concept of art to such an extent that it also includes art mediation, entrepreneurship and inventing.

The present article evades this dichotomy by regarding projects such as these as actor-networks consisting of human and non-human actors which, together, make certain developments possible and/or likely while simultaneously precluding others. Thus, the objective of this article is not to establish Pedersen as an artist or his Systembolaget project as a work of art, but rather to outline how a person with ties to the art world was able to work with existing rules and conventions in ways that make them the object of a non-targeted or function-oriented mode of thought. A mode of thought in which the poster also finds its own place, albeit not as art.

Inventions and art projects

Knud Pedersen expresses obvious relief in the concluding sections of a text about an invention that never progressed beyond the test stage. “For several years now the completed model has stayed right where it is,” he states, “and it sits very well there as a memento of a time that was rich in experience within a field that is otherwise alien to me. There appears to be no limits to the wealth of possibilities that can be explored even with just a little thing; turning it this way and that so that it is viewed from all sides and in all functions imaginable.”2 Once a thing has been created, further development is no longer possible. It is characteristic of Pedersen that he prefers to keep the future open.

The quote is from the chapter “Rundkørslen” (The Roundabout) in his book Erindringer fra disse år (Memoirs from These Years) (1980). The text concerns an attempt to create a ‘car guide’, a kind of pre-digital GPS device controlled by punched cards. The driver would punch holes in the card while referring to a street map, and the car guide would then offer directions every time the car indicators go on (turn left, turn right, go straight ahead …). The text describes Pedersen’s progression through the system, right from his initial visit to the Danish Technological Institute’s office for new inventions up until the final rejection, but the main point of the text is his thoughts and deliberations and how they change along the way.

One of the things accentuated by Pedersen is the fact that his interests differ from those of the other stakeholders involved, regardless of whether they are civil servants, private individuals or artists. The office for new inventions was set up in order to ensure that Danish inventions benefit Denmark as a whole, but Pedersen only wanted to develop a single car guide for his own personal use. The artist Eric Andersen accuses Pedersen of ‘object fetishism’ and makes him admit that the project as such is more important than the car guide in itself, but Pedersen never lets it go entirely. In his hands the project never becomes a marketable product or a conceptual work of art; rather, it becomes a lot of different things that are neither one thing nor the other. He develops a number of games such as the Car Relay Race (“with built-in meaninglessness”), Car Tag and Car Hide-and-Seek. He envisions an “exciting toy for artists and other road users”, asking contacts abroad to use a range of special symbols to give him a route that he will then proceed to follow. He writes “The Roundabout”. And of course the project gives rise to plenty of documentary material (now housed in his private archives) and a prototype (now housed at the Danish Museum of Science & Technology, Elsinore).

The final sentence in “The Roundabout” reads: “No guide could tell me in advance about the pathways I have traversed with my guide in order to help it reach its final destination.”3 Perhaps the term “final destination” is misleading here (Pedersen uses the Danish “endestation”, meaning end station, terminus). Perhaps there is not just one final destination; rather, this is an example of an idea that continues to branch out and proliferate during the course of its realisation, taking on an increasing number of forms. In the introduction to another text in his Memoirs Pedersen describes his approach in these terms:

The next case has not yet been realised. When I portray it nevertheless, it becomes a novel, a fiction. In this way it will illustrate the great gulf that separates the realised (or that which has been attempted to be realised) and the dream or idea which is just waiting to be realised, or which has no wish to be translated into reality, […]. I will, then, portray this next case that I am facing, but which is as yet only an idea, the way it might be imagined to evolve as it is realised.4

The key thing here is not the original idea (the dream), its realisation (the product) or a description of the passage from idea to its potential realisation (the text), but rather the development process and everything it entails. Pedersen’s endeavour has no object, or certainly no object that can be conclusively described, and describing what he is actually working on is equally difficult. All his projects, whether in the form of art, art mediation, inventions or entrepreneurship, can be subjected to this approach, and this fact also makes Pedersen himself rather difficult to pin down. Is he an artist, a presenter of art, an inventor or an entrepreneur? Is he all of these things at once? Or do we miss the point by even trying to characterise his work in such clear-cut terms?

This article will contemplate and describe Pedersen’s overall work by focusing on a single project, Systembolaget, also known as Auktion og flaskepost (Auction and Message in a Bottle), from 1976.5 Even though the project relates to the realm of art, the article will employ a method that originated in the study of Science, Technology and Society (STS): the Actor-Network Theory. Formulated in the 1970s by thinkers such as French engineer and sociologist Michel Callon, British sociologist John Law and French anthropologist and sociologist Bruno Latour, ANT sees facts and objects as the result of interhuman negotiations rather than as rational constructs. Instead of looking for general, universal links between cause and effect, ANT analyses the specific interaction between human and non-human actors in a network. Even though the method originated in STS studies it is also suitable for analysing Pedersen’s work, partly because of the key role played by social interaction, rules and conventions in his projects, and partly because he takes the same approach regardless of whether he is working on an invention or with art. One of the concepts from ANT that will prove important towards the end of the article is that of the ‘black box’, a term used to denote facts and technical objects that we no longer think about or reflect on. The article refers in particular to Latour’s Aramis, or, The Love of Technology (1996), which addresses a shelved project about driverless passenger transport, also known as personal rapid transit. The book has been chosen as a central point of reference because it analyses the differences between conventional and innovative projects and places emphasis on the processes that precede the end result.

The present analysis of Systembolaget as a process and project comprises four stages. The next section introduces Pedersen and some of the terms that he himself used to describe his role and working methods. The following section describes the actual project and its progression, while the third section analyses the network involved. The final section contains a range of concluding remarks on what the project consists of now that Pedersen can no longer take part in its further development.

The mini-onaire, the project maker and the art of failing

Born in Grenå in 1925, Knud Pedersen grew up in Aalborg, where he was one of the founders of the Churchill Club during the Second World War. His involvement in the realm of art took its beginnings in the late 1940s and was launched by a kind of rite de passage. In his book Kampen mod borgermusikken (Battling the Bourgeoisie) (1968)6 he describes how he cut up all his paintings and knocked the heads of all his sculptures. “I was more interested in what art could be used for at all,” he states.7 One of the things that art could be used for turned out to be rental services. In 1951 Pedersen founded Byens Billede (City Pictures), a network of artists’ easels placed in various locations around Denmark (and, later, in Norway and Sweden too), presenting a selection of high-end Danish contemporary art to passersby. Pedersen did not champion just one particular group; he exhibited the so-called mørkemalere (‘dark painters’, a loosely affiliated group of artists focusing on dark earthy colours and landscape motifs) as well as lyrical and geometrically abstract painters. The key objective for Pedersen was to give as many people as possible access to art. Byens Billede represented an entirely new approach to the presentation of art, but it did not require a new type of art. The art of painting and the individual artist figure formed the starting point for the project – indeed, they were prerequisites of it.

From 1955 onwards it also became possible for private individuals to rent paintings from the stock of art that Pedersen used to supply the easels. This eventually led to the opening of Kunstbiblioteket (the Art Library) in Nikolaj Kirke, a former church converted into an art venue in Copenhagen. [fig. 2] The didactic aspect became less important, but the main objective – giving as many people as possible access to art – remained central. At this point Pedersen also became acquainted with the German artist Arthur Køpcke, who lived in Denmark, and Køpcke directed Pedersen’s attention to a kind of art that could no longer be called painting or sculpture. We have Køpcke to credit for the fact that Kunstbiblioteket hosted the first-ever Fluxus festival in Denmark in November of 1962, and for the fact that Fluxus art was one of the key points of reference for Pedersen ever since. Fluxus demonstrated how everyday actions could (perhaps) be art, breathing new life into Pedersen’s organisational activities. He sought to introduce the jukebox as a tool for presenting art (Jukebokse med særligt program (Jukeboxes with a Special Programme) (1963 – never realised)), exhibited art on the back of the Faxe brewery’s delivery vans (Faxe kører med kunst (Faxe Delivering Art)(1965)) and experimented with using Kunstbiblioteket’s answering machine as an exhibition space (from 1967).

In addition to Køpcke, Eric Andersen was another major influence on Pedersen’s work, and we know from letters exchanged between the three that they disagreed on the artist’s and the presenter/mediator’s role and position in projects such as these. Pedersen believed that the changes seen in the role of the artist also affected the activities and status of those who presented art, but the others did not agree. Pedersen argued that when the artist no longer engages in creative activity, preferring instead to explore what is already there, an art presenter like himself can reasonably regard himself “as an agent for the artists – and the artists […] as agents for [his] ideas.” Artist and art presenters both work as agents for art, “or, to be more accurate, for the artistic view of the world.” In mediation projects such as those listed above the crucial element remains the content supplied by the artist, but the medium, the mode of presentation, is also important. As Pedersen states, everyone is an “employee involved in the publication of the magazine called art, in which the typesetter and the editor-in-chief and the buyer of the magazine are all equal.”8 Art is no longer a thing, but a way of viewing the world, and everyone involved in shaping this gaze on the world is a co-creator.

Pedersen’s new view of the role of the art mediator prompted him to emerge as an artist himself in 1967 with a contribution to the juried Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling (The Artist’s Autumn Exhibition) called Alle verdens telefonbøger og en telefon (All the Telephone Books in the World and a Telephone) – a title that very succinctly describes the work. His idea about the art presenter’s role also meant that Denmark was confronted by an ever-growing flow of projects from his hand that presented art created by others in ways that in themselves represent a distinctive idea; a process that Pedersen described as ‘idea escalation’ in 1970. One example would be Byggeprojektet (The Building Project) (1968), which strictly speaking comprises three proposals, formulated respectively by Eric Andersen, George Brecht and Arthur Køpcke, for high-tech works of art (environments) that would cost a total of DKK 6,059,000,000 to realise. To fund this project Pedersen successfully negotiated a particularly advantageous interest rate with the Bikuben Bank, ensuring that the amount required would have accrued by the year 2252. In a book about the project he reproduced compound interest tables that show how much an amount of DKK 1, DKK 50 or DKK 100 would grow from one year to the next over a period of 285 years, “so that each artist can see the timeframe for the completion of their project as regards the financial demands imposed by the use of sophisticated technology and the opportunities usually available to artists for meeting such demands while still maintaining their full autonomy.”9 Here, the works of art are placed within a framework that expands their scope and validity, a framework that can to some extent – certainly if one accepts Pedersen’s argumentation – claim to be a work of art in itself.

One of the terms that Pedersen introduced to describe his own role is that of ‘miniardær’ – a pun replacing the ‘billion’ in the Danish term for ‘billionarie’ with ‘mini’ to arrive at ‘miniadaire’ or perhaps ‘mini-onaire’. He defines the concept on the back cover of a book bearing the same title as “a person – in this case a man, father, and grandfather – who has a vast quantity of things that are all characterised by having no financial value and by being entirely useless, except for this book.”10 The wealth of a mini-onaire can only be used for this particular book: this in turn means that only Pedersen can be a mini-onaire. Indeed, he dedicates the book as “really for family and friends”, adding that: “I apologise to uninitiated readers for the limited gratification they will derive from this work.” This is followed by an account of a potential American film based on his book Churchillklubben (The Churchill Club) (1945), conceptual Christmas trees to celebrate his 75th birthday, and a football match played in the dark.

Another concept launched by Pedersen in a book title is that of ‘project maker’: in 1970 he publishes a book called Skitser til en idéescalation fortalt af Projektmager Pedersen (Sketches for an Idea Escalation as told by Project Maker Pedersen).11 The book describes the term only implicitly by offering a rundown of a range of projects – not, it should be noted, just his own. Valie EXPORT’s Tapp und Tast-Kino (1968) and Ay-O’s Finger Boxes (1964–) are highlighted as examples of ‘touch cinemas’, and works by Eric Andersen and George Brecht are brought forward as examples of “collaboration/identification between art and the business world.” Of particular interest in connection with his role as a project manager are the concluding words in a chapter concerning a proposal to change the time on the clocks on the tower of the Copenhagen City Hall so that you would need to walk all the way around the tower to figure out what time it is. He states:

Why such trouble to establish the exact time? If you feel slightly sorry for the passerby who finds upon glancing at the clock that he is too late and must hurry up, you can also rejoice along with the one who approaches from the other side and discovers that he can allow himself a bit of extra time. Most of all, you can cheer along with the person whose path crosses that of the other two as he discovers that he is not in fact heading for work, but going back home again with the day’s work done.12

The project maker does not take sides; not because he does not care, but because positive and negative responses are both results of the project and should be accepted as such. The project maker does not necessarily organise his own projects; he might equally well assist others. His contributions are often quite modest. The (art)work – if indeed it can be described as such – arises where the idea ‘escalates’. The art aspect of his contributions can be found where organisational work, no matter how modest, opens up new horizons. The project maker creates projects plus something more that may be captured in a text, in a new project or in a work of art, but which may also just be something indefinable in the air.

A third concept is ‘the art of failing’. Pedersen’s book of this title (Kunsten at mislykkes) was published in 1981.13 It too describes a range of projects; not necessarily projects that failed, but certainly projects whose success is difficult to measure. Sommeren på Meilgaard (The Summer at Meilgaard) describes Eric Andersen’s work on a son et lumière performance that ended up being cancelled. Københavns museum for moderne lovgivning (The Copenhagen Museum of Modern Legislation) describes a project of legislative proposals that never progressed beyond the stage of the museum’s own legislative decrees – and did not need to do so. Et berømt museum der ikke findes (A Famous Museum that Does Not Exist) is about Københavns Museum for Moderne Kunst (The Copenhagen Museum of Modern Art), a museum that exists in name only, but which nevertheless manages to host all sorts of art projects.

Pedersen includes a description of an unrealised project in which the onset of the Christmas shopping season is celebrated by giving some money to a member of Vedbækgarden, an all-girls marching band. Wearing her band uniform she would then enter a supermarket and buy something she feels would fit the person whose money she is supposed to spend. Pedersen’s description ends with the following passage: “Even if the performance were carried out, it was never intended to reach any final conclusion, but as things turned out it never progressed so far as to establish any firm date for its performance. Nevertheless it did exist, the way that […] a written play only possesses a certain kind of reality before it is performed in another reality, on the stage.”14 In other words, projects exist on several levels and in several forms. They can be brought to fruition, but they can also simply act as food for thought. The art of failing points to the difficulties inherent in assessing something that evolves backwards, from dead to alive, and which exists as a potentially endless series of opportunities instead of constituting just one reality.

The mini-onaire possesses riches that cannot be described in terms of fixed figures and which cannot be reduced to anything other than what they are. The project maker does not deliver a single final product; rather, he sets a process in motion that gives rise to all sorts of things, including some that cannot be measured. The art of failing suggests an attribution of value that is based on the process rather than on the end result. It is easier to find words to describe what Pedersen is not, what he does not do, rather than to describe what he is and does. One possible solution would be to describe his work as an actor-network instead of as a stable object that is imbued with meaning in accordance with how it is incorporated into different situations or contexts. Below, the project Systembolaget from 1974–76 will be described as a test case for this kind of analysis.

Systembolaget

Systembolaget is described in a chapter of The art of failing bearing the heading “Bertil in Boberg”.15 The text concerns an old farmhouse in Halland that Pedersen had recently bought, and a Swedish alcoholic, Bertil, who was one of Pedersen’s neighbours there. The story begins with Pedersen pondering the information campaigns launched by Systembolaget and the case of Bertil, who “has official confirmation that he is one of the hundreds of thousands of people who drink too much no matter what is done to help them.”16 Bertil tells Pedersen about the strange and tragic figures that make up the local community and introduces him to the alcohol habits associated with that community. This takes place against the backdrop of Sweden’s recent transition from left-hand traffic to right-hand traffic, an event that looms large as a vast project that changed the entire appearance of the nation.

While Pedersen reflects on Systembolaget’s campaigns and Bertil’s stories he is hit by the notion that it might be interesting to stage an exhibition about Systembolaget, highlighting its distinctive nature as one of the very few enterprises in the world whose objective is to prevent its customers from buying what they sell. He sends an inquiry to Systembolaget and receives a parcel of brochures and posters. Shortly afterwards he receives a visit from the superintendent at the Malmö branch of Systembolaget who wants to hear more about his plans. At this point Pedersen has already decided that he wants to include a bar in the exhibition, but he makes no mention of this to the superintendent. Instead they speak about Systembolaget’s window displays and about the things Pedersen would like to borrow. The representative must have consulted the main office in Stockholm after his visit, for a few days later Pedersen receives a letter informing him that Swedish alcohol policies cannot be represented out of context and that for this reason Systembolaget refuses to take part in the exhibition.

Pedersen does not give up that easily. He asks the Danish poet Jørgen Nash, who lives in Sweden, to go to Stockholm to speak with the managing director of Systembolaget, Rune Hermansson. Nash succeeds in securing an appointment with the managing director, but their meeting yields no concrete results. Nevertheless, Nash is allowed to view a museum showcasing items from Systembolaget’s past; a museum that is not open to the general public. Here he sees pistols that were issued to Systembolaget employees so that they could defend themselves against assaults from customers, illegal stills and plenty of propaganda materials. Soon afterwards Pedersen visits Stockholm himself, accompanied by Nash, but once again without result, and a few weeks later Pedersen receives a letter in which Hermansson firmly distances himself from any proposed attempts at presenting Systembolaget in an exhibition in Denmark, prohibiting the use of the posters previously sent to Pedersen.

As Pedersen states, this rejection “did nothing to lessen my interest in creating an exhibition in one way or another.”17 He hits upon the idea of staging the exhibition as a “flaske- and kastepost” event – a rhyming play on words meaning “message in a bottle/thrown mail” event – that would involve sending messages to Systembolaget in the form of messages in bottles. Pedersen intends to construct a trebuchet, a kind of catapult, to hurl the bottles out into the Sound separating Denmark and Sweden. He also toys with the idea of sailing express messages in bottles out to the edge of Danish territorial waters to speed their progress. He mentions a cutter formerly owned by Danish king Christian X and how the vessel’s current owner would be happy to make the ship available for the project.18

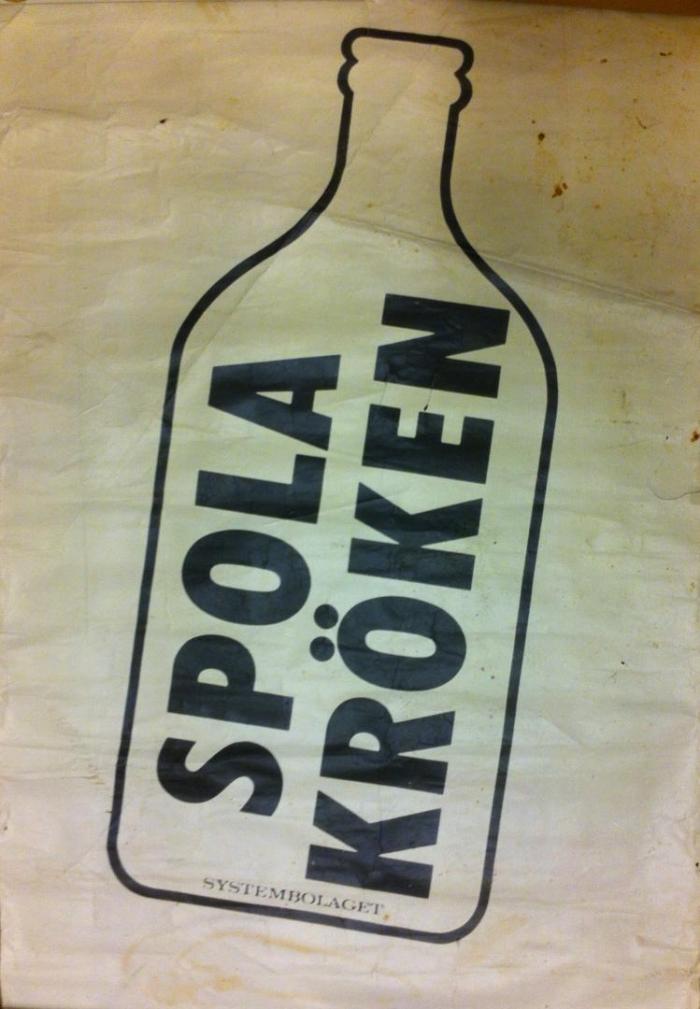

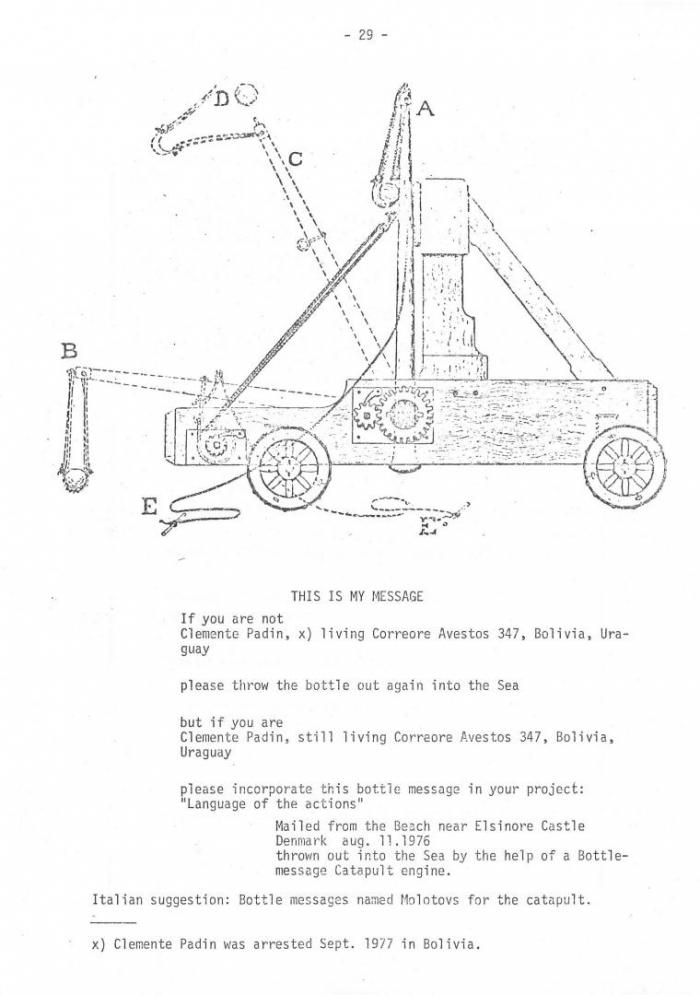

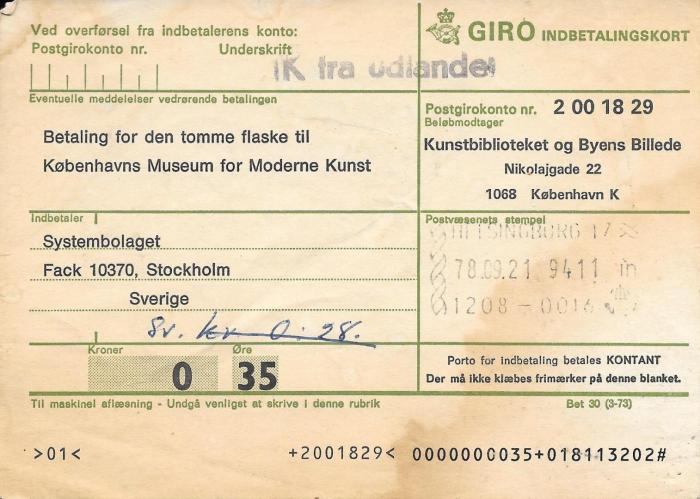

In preparation for constructing the trebuchet Pedersen borrows Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey’s book The Projectile-Throwing Engines of the Ancients from 1907, [fig. 3] and gets in touch with General Permin from the Danish Home Guard to enlist his help on having the machine built. During his conversation with the general Pedersen omits to tell him that the machine will be used to send messages to Systembolaget, an omission that helps his cause: Permin is on board. According to Pedersen’s description of their meeting, Permin was annoyed with the Swedes because they always insisted on showcasing sites where they had bested the Danes in battle in the past, and Permin was also intrigued by the idea of “non-technological means for communicating across the Sound.”19 A number of Home Guard soldiers were placed at Pedersen’s disposal, arriving at Boberg to build the trebuchet, [fig. 4] and there were no problems about shipping it to Denmark: the customs officers “regarded the vast monstrosity with curiosity, but it all resolved into amiable goodwill when we stated that this was a secret weapon.”20

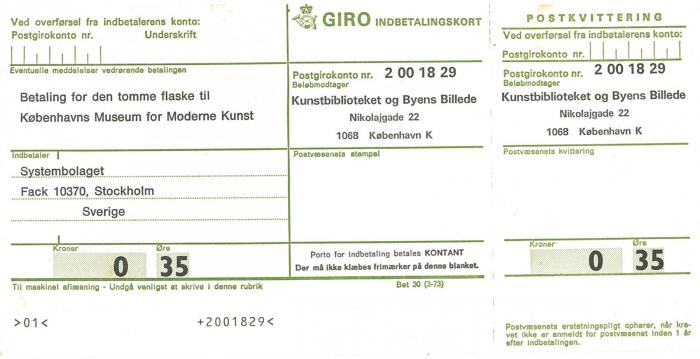

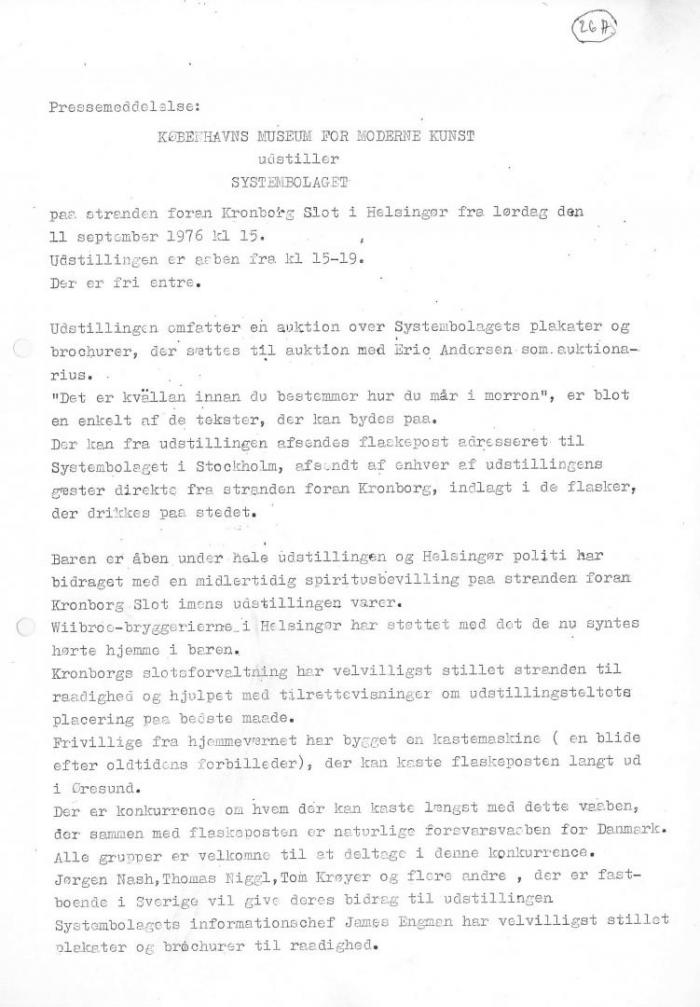

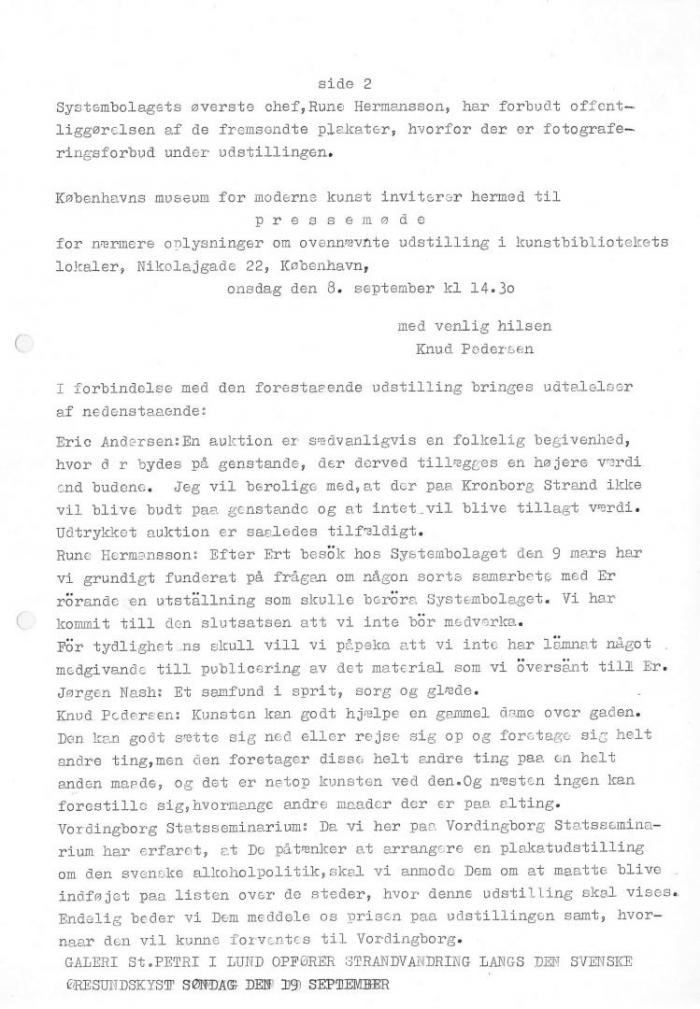

The acme of the project so far occurred on 11 September 1976 on the beach by Kronborg castle in Elsinore. On that day a temporary barrack is set up to host an auction of Systembolaget posters, and the trebuchet stands by the edge of the water. [fig. 5] Eric Andersen has devised an auctioning system where the posters are bid for in the form of ‘units’ purchased from a bar installed inside the barrack. All units must be purchased, and the highest bidder gets a poster with their purchase. On the beach the trebuchet is flanked by a wagonload of pine trees bearing Christmas ornaments; the wagon was driven down from Sweden by Jørgen Nash. Next to the trees is a sign saying “Et samfund i sprit, sorg og glæde” (A Society Soaked in Spirits, Sorrow and Joy). The choir of the temperance society (Nykterhetsförening) of Southern Sweden were also invited to attend and sing drinking songs, but nothing came of it. The bar, however, does a roaring trade. Bottles are emptied, those present write messages to Systembolaget and put them inside the bottles which are then sealed with sealing wax. A giro form is added to each bottle, enabling the recipient to pay the bottle deposit (30 øre). [figs. 6 and 7]

In his text, Pedersen is at pains to emphasise that the entire event is completely legal. The Danish Ministry of Housing has granted permission for the use of Kronborg beach, the barrack has been approved by the castle authorities, and the Elsinore police has issued a temporary licence to serve alcohol. The Wiibroe brewery supplies beer free of charge and quite voluntarily, the Danish Home Guard provides a power generator and employees from Kronborg Castle monitor the proceedings dressed in uniforms and with walkie-talkies in their hands.

The text concludes with a remark stating that “the actual event was an anti-climax after the painstaking preparations. The exhibition about Systembolaget was forgotten”, says Pedersen. “Systembolaget continued. A newspaper reported the event under the heading ‘Oh, what a pitiful war’. And I suppose it was. It took place entirely without any hussars, and as yet only one bottle deposit payment has reached Copenhagen from Elsinore.”21

Upon reading “Bertil in Boberg” the reader is left with a sense of having lost or missed the point. Why did I read this account at all? Where is the art in all this, and where is the failure? What failed? The project was in fact carried out, so perhaps the actual Systembolaget is the failure? After all, the Swedish alcohol policies failed to keep Bertil away from alcohol. On the other hand, Pedersen himself states that the ‘exhibition’ disappeared, and that Systembolaget survived.

Part of the answer can be found in the press release. [figs. 8 and 9] Written in Danish, the first sentence reads: “The exhibition includes an auction of Systembolaget posters and brochures held with Eric Andersen as auctioneer.” Here the exhibition or art presentation medium is reformulated and reinvented as an auction. The next line states that “from this exhibition [visitors can] send messages in a bottle addressed to Systembolaget in Stockholm […] inserted into the bottles emptied on site.” The auction is the central part, the messages in bottles is an activity that follows in its wake. The third element of the press release is an enumeration of all the authorities and enterprises that have contributed to the project. The Elsinore police, the Wiibroe brewery, the Kronborg castle authorities and the Danish Home Guard are all mentioned by name, and the press release also includes a remark stating that “Systembolaget’s head of communication James Engman has kindly [placed] posters and brochures at our disposal.”

This list is rather abruptly followed by a description of the trebuchet as a “weapon which, alongside messages in bottles, is a natural weapon of defence for Denmark”, an element that plays no role at all in “Bertil in Boberg”, but which is strongly emphasised in the press release. Describing the trebuchet as a weapon introduces a new spin on the text because it is followed by the announcement that the head of Systembolaget prohibited the publication of the posters received, “for which reason photography is prohibited during the exhibition.” The whole thing is legal, but only barely: only by repackaging the event as an auction and by prohibiting photography can the rules be obeyed. Pedersen is quoted in conclusion:

Art can help an old lady across the street. It can sit down or get up and do entirely different things, but it does these entirely different things in an entirely different way, and that is the art of it. And almost no-one can envision just how many other, different ways everything can be done.22

According to Pedersen’s definition, art consists in doing quite ordinary things differently. Systembolaget can be presented in an exhibition in many ways, and this is an artistic way of carrying out that task. The press is encouraged to focus on how the project was planned, not just on what can be seen and experienced at the event in itself.

In addition to “Bertil in Boberg” Pedersen wrote two other – unpublished – texts about the project. One offers a more detailed description of the project’s inception, the other is a kind of assessment of it. “Bertil in Boberg” appears to be an excerpt of the former text, highlighting what Pedersen left out. First of all, this concerns the relationship between Denmark and Sweden. His description bears the title “Kulturelt samarbejde Danmark/Sverige omkring Systembolaget” (“Cultural collaboration between Denmark/Sweden concerning Systembolaget”), and his introduction emphasises the fact that Denmark has “no corresponding restrictions on the purchase of beer, wine and spirits.” A thematic counterpart to this passage appears later in the text as Pedersen describes Swedish art acquisition policies. He states that the local authorities of Stockholm spends DKK 2 million on art every year, four times as much as the Danish Arts Foundation, but also that their choices are infused by “dreadfully good taste: based on the majority vote of the art professionals on the acquisition committee. Nothing mad, nothing insane, nothing unsuitable for furnishing this over-furnished urban setting which, with vases instead of sculptures and carpets instead of paintings or reliefs, seems lethally stifling.”23 Here we find a theme that is underexposed in “Bertil in Boberg”: government management versus individual responsibility.

The text also adds insight into the process. “Bertil in Boberg” only refers to the creation of the elements that made up the event on the beach at Kronborg on 11 September 1976, but not the ideas and plans that were never realised. For example, Pedersen describes two of the ideas he had after his failed meeting with Hermansson in Stockholm, having realised that he would be unable to stage an exhibition per se. One of these ideas was to have a raffle with alcohol as the prizes. The other was based on the Danish expression ‘plakatfuld’, literally ‘poster-drunk’, meaning exceedingly drunk. Pedersen wanted to print some of Systembolaget’s posters in a format that corresponded to the side of a lorry, 22 x 2.90 metres. The posters were intended by the carried from Gothenburg to Stockholm on barges. From here they would be put onto lorries and brought to Helsingborg, continuing to Denmark where Danish customs officers would reject this import.

The ideas are closely related to the issue of alcohol policies, prompting Pedersen to reconsider the objective behind the exhibition: “Where does art enter the picture?” he asks and answers his own question as follows:

Art enters the picture where this entire external apparatus [state management of alcohol consumption versus the free market] is just an artistic motif which […] the right idea can bring to the fore as a qualified memory, an addition to their museum in Stockholm, not an exhibition of their museum; this fundamental difference between art and mere exhibition which makes it so important to demonstrate examples of the new view of art […] regardless of the fact that the process can often make it difficult to take this seriously because it has equally grotesque results, for example this act of showcasing ‘the System’ via the Danish society’s absence of a corresponding system […].24

While considering different ways of exhibiting alcohol use and abuse and the role played by the state in inhibiting or promoting such (ab)use, Pedersen arrives at the conclusion that the main focus should not be alcohol or the alcohol policies of a specific state, but rather the overall relationship between law and freedom. Thus, the exhibition should not reproduce Systembolaget’s own museum, but instead constitute an addition to it: In other words, it should constitute a new phase in the organisation’s life, one that leaves its own tracks.

The “Bertil in Boberg” text mentions Eric Andersen only as the author of the auction system and as the auctioneer, but “Cultural collaboration between Denmark/Sweden concerning Systembolaget” describes his role as much more extensive. Upon his return from Sweden – perhaps even sooner than that – Pedersen discusses his idea with Andersen, and according to the text Andersen is the one who suggests using the cutter previously owned by Christian X. They also set out together to look for suitable locations from which to launch messages in bottles by boat or catapult; one of the locations chosen was the Tuborg harbour with its two lighthouses shaped like beer bottles. They also conducted a joint visit to The Royal Danish Arsenal Museum that led to their discovery of Payne-Gallway’s book on projectile-throwing engines. Perhaps it is because they were not allowed to use the Tuborg harbour and because they never used the royal cutter; whatever the case may be, “Bertil in Boberg” certainly downplays Andersen’s role to focus instead on the project’s final form and on Pedersen’s role in its inception.

And yet. Another aspect accentuated in “Cultural collaboration between Denmark/Sweden concerning Systembolaget” pertains to all the practicalities involved in staging the project. While the document does not provide a complete inventory of these tasks, it does mention things like getting quotes for renting, erecting and dismantling a party tent as well as for bar rental and printed labels,25 constructing the trebuchet, printing giro forms to be inserted in the bottles, getting quotes on raffle booth rental, obtaining a temporary licence to sell alcohol, and possible methods for sealing the bottles (corks, candle wax, or tallow?). All this may seem banal, but it does touch on the question of where the ‘art’ aspect of this endeavour can be found. Pedersen spoke about “the right idea”, but if the nitty-gritty of organisational work is the mainstay of the work, tasks such as these are its tools.

Another difference between the two texts merits attention in this context: in “Bertil in Boberg” Pedersen makes no mention of the arguments he used to persuade the various reluctant or unwilling participants, but he does so in “Cultural collaboration between Denmark/Sweden concerning Systembolaget”. During the conversation between Pedersen and Hermansson in Stockholm, Hermansson said that he was afraid that Pedersen was only interested in making a cheap jibe at the Swedes’ expense. It was not his job to sell alcohol, but to “reduce human suffering”, and he believed that the exhibition might harm this effort. Pedersen replied that the Danes had actually taken over many things from the Swedes, quoting the transparency principle (principle of public access) as an example of something that the Swedes had already had in place for a long time, but which the Danes had only just adopted. In other words, he was open to the idea of the exhibition acting as propaganda for the Swedish system – an argument that also appeared in his first letter to Systembolaget, which describes the campaign as “interesting, skilfully made and featuring content that might also interest Danish audiences.”26

Another thing missing from “Bertil in Boberg” is a description of Pedersen’s changing perceptions of his own role and the shifts in how he presents himself in his negotiations with the various stakeholders. During the time when Andersen appears to have been most strongly involved, Pedersen sent applications to the Danish brewery organisation De Forenede Bryggerier A/S, requesting permission to use the Tuborg harbour. He also applied to them and other alcohol manufacturers for sponsorships, but the rejections received to these requests and the Systembolaget’s refusal to allow him to use the posters made him feel like a “lonely soldier” and a “terrorist”. He now regarded the trebuchet and the messages in bottles as suitable matches for the role of a lonely freedom fighter, easy to make and to operate. The Sound was also cast in a different capacity, now appearing as a reference to the many people who fled to Sweden during the Second World War, and to the sea as ‘the Road of Danes’. And it helped his cause with General Permin that he only had to identify himself as Knud Pedersen from the Churchill Club to secure an appointment to see him. During their conversation Pedersen never had to state that the project involved messages in bottles intended for Systembolaget: the theme of Denmark versus Sweden, war and resistance, was sufficiently rich in arguments to persuade the general. The strategy of saying nothing about Systembolaget also proved effective with other stakeholders involved: Pedersen quite simply asked for permission, and permission was granted.

The issue of argumentation plays a major part in the third, untitled document that constitutes a kind of evaluation of the project.27 Here Pedersen describes it as a “hijacking”. He states that the crucial aspect is not what happened on the beach at Kronborg or during his negotiations with the parties involved. The thing that made the project a hijacking was the fact that he might as well have worked on behalf of “Christianianites [inhabitants of the self-proclaimed autonomous commune Christiania in Copenhagen] or other revolutionaries”, and that he persuaded the Wiibroe brewery to deliver beer for “an attack against a potential customer who was about to be hit over the head with empty bottles.” He states that what transpired was as far removed from an exhibition about Systembolaget “as the Home Guard were removed from their usual function, the castle from its function and the Elsinore licencing police from their usual function.” Using existing institutions and systems in ways that were entirely proper, yet held the potential for illegality: that was the crux of the project.

Jørgen Nash, whose presence at Kronborg is mentioned only in one sentence in ”Bertil in Boberg”, plays a key part in this context. Pedersen states that Nash’s contribution demonstrates the difference between conceptual art and happenings. In the text Pedersen reveals that there had been talk of staging a two-day event, and that it was agreed that Nash would get Sunday. However, Pedersen only got permission to use the beach for four hours on Saturday, leaving no room for Nash’s contribution. Sunday became the day of the revolutionaries, and Nash acted accordingly: he disrupted the auction by loudly nailing posters onto the party barrack, he kept the bar open after its temporary licence had expired, and the whole thing ended with tables and chairs having to be fished out of the sea and with the barrack awash with sand and garbage. According to Pedersen, the moral of all this was: Nash had, like the authorities and the Wiibroe brewery, paid more attention to the event as such than to the idea. Happenings like the one Nash ended up performing are about form while conceptual art is concerned with content, and “the content could find expression anywhere and with any starting point, whereas the situation was closely associated with the site, the motif, and all the superficial paraphernalia and settings that surrounded them.”28

Project and network

As Bruno Latour says in Aramis, projects are always fictions: at the point of their beginning they do not exist.29 They begin their existence as plans, i.e. as signs, language and text; only when they are brought to their final conclusion do they become objects.30 Pedersen’s project began with a vague desire to create an exhibition about Systembolaget. The moment he wrote his first letter the thought became paper, but the object did not yet exist. The auction and trebuchet had not yet entered the picture, and from this perspective they cannot even be said to have existed in potentia or implicitly in Pedersen’s initial thoughts.

When he first launched this project he only knew that he wanted to create an exhibition, but he had no mental image of what it might look like.31 Not until Systembolaget made their first objection, stating that their posters cannot be understood without proper background information about Swedish alcohol policies, did he feel compelled to be more specific. For example, he mentioned a working title in his second letter, “The distance between man and image”, adding that the posters would “form part of a wider context that will offer an artistic spin on the excellent texts, which are unknown to Danish audiences.”32 As an example of such an “artistic spin” he enclosed a copy of the publication about the 1968 Building Project, mentioned above as an example of ‘idea escalation’. Pedersen did not intend to exhibit Systembolaget for its own sake, but in order to introduce more widely applicable thinking.

Right from the offset the project is subject to different and diverging expectations, and the process becomes even more complicated when Pedersen begins to omit certain things when speaking to various stakeholders. This happens from an early stage: in his conversation with the Systembolaget representative in Malmö he chooses not to mention that he would like to include a bar in his exhibition, and when the realisation of his project draws near and he must get the Home Guard, the castle authorities and the Elsinore police involved he remains silent about Systembolaget. What began as a misunderstanding, motivated by the various actors’ own everyday focus areas, becomes a deliberate game that plays around with different roles: what functions do the different actors have, and how can the project be presented to them in a manner that appears to fall within the scope of their usual day-to-day work?

The issue is complicated further by the fact that everyone involved acts as spokespersons for a group and/or represent a particular role or identity, and that these references are constantly shifting and changing. The Home Guard is there for the people, the police and administration are there for the citizens, and all three represent the state. Pedersen’s part changes depending on the actors with whom he deals. To the Systembolaget representative in Malmö Pedersen is a suspicious artist type, to Rune Hermansson he is a Dane wanting to make a joke at the expense of the Swedish alcohol legislation. In order to secure an appointment with Hermansson, Nash presented Pedersen as the right-hand man of the Danish Minister for Culture, but it is unlikely that any mention was made of the Ministry of Culture when Pedersen showed up in Stockholm himself. In Pedersen’s own accounts Andersen’s status changes from that of a key collaborator and main supplier of ideas to being just the one who came up with the idea of having an auction and acts as auctioneer. Nash undergoes a transition from being a co-conspirator to becoming a representative of a rivalling view of art.

Latour uses the term ‘translation’ to describe the negotiations that surround projects in development.33 A project is created in many different versions depending on how the people involved perceive it – how they interpret their own position and those of the other participants. The only thing that stabilises them to some extent is legally binding agreements. In this case those agreements were not established until the very last minute: the permission to erect the pavilion and to serve alcohol are examples of this, as is Rune Hermansson’s prohibition against using the posters in an exhibition, although the actual legally binding power of this prohibition was never put to the test. Yet another example is the permission to use the beach in Kronborg. The agreement explicitly forbade the act of throwing anything in the water, so according to Pedersen the trebuchet was never used on the beach; the bottled messages were thrown into the water by the marina instead. Regardless of whether these injunctions and permissions form the framework around the work or constitute elements of the work itself, these agreements are certainly solid parts of the structure of the work. Many of its elements are unpredictable, but they have been systematised to take on the effect of firm rules. At the outset of the project none of the people involved knew that they would play a part in it, but they ended up being important contributing factors. In this sense the agreements take over the lead from the living actors: regardless of what the people involved might think about it, the rules must be obeyed. The rules are reliable, unlike many other things that had to be invented from scratch.

The authorities had to give permission, but so too did the objects. Here, the term ‘permission’ should be seen metaphorically: for example, the point of departure always was to present Systembolaget through their own information materials, meaning that the distinctive qualities of these materials would govern what was and was not possible. Making payments in ‘units’ resulted in plenty of empty bottles that practically begged to be used for something. The currents of the sea required the bottled messages to be thrown into the water quite some distance away from the coast. Ascribing agency involves the risk of anthropomorphising inanimate objects, but we can certainly say that specific circumstances limit the range of possibilities available and suggest particular solutions over others. If the work in question had been a painting, each of these ‘brushstrokes’ could be ascribed to the artist’s brilliance, but here they appear rather more like material enablers that combine to shape and/or facilitate the final project.

Latour states that a project can be described as ‘innovative’ when it is not clear beforehand how many actors/actants – once again including objects as well as people – are involved.34 If all actors are known in advance, the project in question can evolve towards an ever-increasing degree of reality via a series of well-ordered, hierarchical stages. Innovative projects are not as ordered as that. In innovative projects you do not know what allies you will have; you do not even known by which criteria the project will ultimately be assessed. Only when a result appears will everyone involved have a stable object to which they can relate.35 The process leading up to this result may well be characterised by mutually incompatible accounts, for example when the various stakeholders have different expectations or agendas. This is clearly evident in the negotiations between Pedersen and Systembolaget and in Nash’s changing role. The latter is initially an ally but ends up feeling betrayed even though his contribution fulfils a function in Pedersen’s account by being example or sign of an opposite approach that makes Pedersen’s own appear all the clearer.

According to Latour, a project does not succeed because it is well conceived from the outset. Success only manifests itself after the end of the project, so at most one might say that a project gains or loses reality during the process. Projects have no life to begin with; they need a steady supply of existence, of being, in order to develop a firm existence and to impose their own growing cohesion and context on those involved. Pedersen begins with nothing, but then he gets the posters and, later, a prohibition banning him from showing them in an exhibition. It all snowballs from there until he has a trebuchet, a sponsor, a range of permissions, a pavilion, a power supply and so on. He did not know that a generator installed by the Home Guard would be part of his project when he sent his initial letter to Systembolaget almost two years before. Every time his requests were refused it looked as if the project would remain just an idea, materialising only in a few letters and texts. The road to success turned out to be based on recognising the fact that people were perfectly willing to co-operate as long as Pedersen did not mention the exact nature of the project; as long as he spoke directly into his partners’ worldviews and perceptions of their own roles. This recognition also ended up being the key or main point of the project: that ‘systems’ exist in order to carry out tasks, and that the objective of those tasks does not matter.

Realising Systembolaget took almost two years, and much of that time was a time of stasis and stagnation. Or was it? Even though projects are said to ‘mature’, objective, measurable time is not a relevant criterion. Periodisation and temporalisation occurs through the actors.36 Pedersen set the project in motion, received his first rejection, put it on hold, tried again, received even more rejections, reconsidered and eventually found a form that could be realised. The coalescing that took place along the way was brought about by a clear-cut approach. Because Andersen gave Pedersen a new angle on the project they were able to accomplish much in very little time. Because the application procedures for obtaining the necessary permits were already firmly in place in established systems, Pedersen was able to arrange a lot in the weeks leading up to 11 September 1976. The periods, the intervals, the rapidity or slowness of the project’s progress were dictated by those involved and by what they had to do – were they routine matters or was innovation required? The actors involved quite naturally divided the project into different parts: Pedersen had to negotiate with the Home Guard about the trebuchet, with various breweries on sponsorships, etc. As a result the project became a composite object that did not materialise until the day of its realisation, which in turn also became a kind of test of its strength and cohesion.

One of the most prominent properties of the project is the fact that its subject or content is so changeable. The main focus falls on different themes at different times: on Systembolaget, on the Danish and Swedish models for how the state treats and manages its citizens, or on degrees of state interference and systems in general – without any of these themes asserting themselves fully. Just as the project cannot be said to have evolved in a straight line, it also cannot be said to have stable references to the outside world. The concept of different degrees of freedom and state management was a key issue in the collective consciousness of the mid-1970s, shaped as it was by the Cold War, but the deliberations found here offer no counterpart or adversary for the project against which it might be compared and contrasted through all its stages; nor does it offer any key to a final resolution. Rather, it engages in a constant flux of decontextualisation and recontextualisation. The physical posters prompt the idea of having an exhibition and making the Systembolaget the central focus of the project. The negotiations with Systembolaget about getting the necessary permissions cause the idea about Danish versus Swedish models to take centre stage. The practical efforts involved in organising a day featuring an auction and the launch of bottled messages then shifts the focus away from models to systems. Depending on the actors’ different expectations and plans, various contexts are brought into play, by turns rising towards the surface and sinking back into the depths along with their respective actors.

Projects live their lives in reverse, from dead to alive.37 In between these two stages they take on existence to varying degrees depending on how the people involved perceive the project and on the efforts they make on its behalf. The evolution of projects does not progress in a straight line; it changes its course with every step taken. Projects are not stable entities that merely take on different meanings depending on the context. Meaning and context are integral aspects of the project itself, added and made real by those involved. Assessments are performative matters; speech acts that change the project itself.38 Stabilisation does not take place until the project is complete and the result can be presented to the world; until that point only legally and socially binding agreements can create some form of stability. Systembolaget found some degree of stability in the promises and consents granted in the days and weeks leading up to 11 September 1976. But do the events on the beach at Kronborg constitute the stable end product of the project? There is much to suggest that, given Pedersen’s special view of the project format, this is not the case.

Process and object

The project left behind a number of letters, a press release, some photographs and reviews and at least three written accounts. In terms of stabilising the project, the first question to be asked is whether these materials can be said to document the project: do they offer a full, or at least reliable, account of it? Even though the letters give us dates, names and other formal pieces of information, it soon becomes clear that the project’s paper trail is not unambiguous. For example, ”Bertil in Boberg” states a different date for the ‘exhibition’ than the other texts: the 23rd instead of the 11th of September. In that same text Pedersen states that the Home Guard wore uniform coats while building the trebuchet, but the photographs documenting the event show them wearing plain clothes. Nor does the text mention the dates of several crucial events. Only by referring to the letters does one discover that Pedersen wrote to Systembolaget back on 18 November 1974, and that the definitive refusal did not arrive until 19 March 1976, sixteen months later.

Facts like these not only reveal that “Bertil in Boberg” was not written as a factual account; they also tell us that the text cannot lay claim to being the final word as far as Pedersen’s intentions were concerned. He applies a different angle in all three accounts, so when Pedersen speaks about “the right idea” in “Cultural collaboration between Denmark/Sweden concerning Systembolaget”, he cannot possibly be referring to a single idea that underpinned the entire project. This idea changed as the project evolved and as Pedersen’s view of it changed along the way, but multiple interpretations are also possible after the events at Kronborg had transpired. Viewed in this light, the project did not end on the beach at Kronborg on 11 September 1976; rather, it continues to evolve in the texts Pedersen subsequently wrote about it. And it does not end with the texts. For example, Pedersen mentions that he sent a message in a bottle that was not addressed to Systembolaget at all, but to Clemente Padin in Uruguay. The message was a contribution to Padin’s Mail Art project Language of the Action to which Pedersen was invited to contribute back in 1974. The text of the message was:

If you are not / Clemente Padin, living Correore Avestos 347, Bolivia, Uruguay / Please throw the bottle out again into the Sea. / but if you are / Clemente Padin, still living Correore Avestos 347, Bolivia, Uruguay, / Please incorporate this bottle message in your project: / ‘Language of the Action’. / Mailed from the Beach near Elsinore Castle / Denmark aug. [sic!] 11 1976 / thrown out into the Sea by the help of a Bottle- / message Catapult engine.

The fact that the project was associated with Pedersen’s activities within the realm of Mail Art is also accentuated by the way in which he frames it in his book Den nye fantasi (The New Imagination) (1979).39 Mixing accounts of projects that are definitely artistic in scope with descriptions of inventions and games, the book is a work of art in its own right. It has been cut into four parts, thereby requiring four hands to be read, and is wrapped in plastic and placed on an aluminium tray because the Fluxus artist Milan Knižak once supposedly said that a book is best enjoyed chilled: this book lends itself to being stored in a refrigerator. In The New Imagination the invitation for Systembolaget is included alongside two other works, Experimental Library No. 9 and Bottle-Message. The former consists of a proposal for a ‘catapult library’ where borrowers are themselves responsible for obtaining the book they require from the previous borrower. The latter is a contribution to a project launched by the East German Mail Art artist Robert Rehfeldt from 1977, i.e. one year after Systembolaget. It consists of the following text printed in Danish, French, German and English on a label:

In the regulation of The International Postal Convention there is nothing prohibiting that wrapping is regarded as contents or vice versa, that contents are regarded as wrapping so that for example a bottle may be regarded as wrapping in itself and mailed at letter-rates. Statement given by The Royal Danish Postal Services in reply to an inquiry by The Copenhagen Museum of Modern Art.40

Padin’s project invited artists to comment on a theory stating that actions can be regarded as a language that has a direct impact on the world. Even though Pedersen’s third text describes bottled messages as part of the project’s superficial paraphernalia, individual bottles could nevertheless carry meaning. By contrast, Pedersen’s catapult library operates at the same level as Systembolaget, offering a new way of using and perceiving existing institutions, rules and behaviours. Bottle-Message aimed to dispense with the traditional opposition between form and content – an intention that could also be said to motivate Systembolaget.

The above demonstrates that Pedersen might just as easily frame or continue to develop the project in other projects as he might continue to describe it in new ways in his texts. Determining exactly what the work is becomes impossible, and even the question of what it might be is misleading: if it is possible to prepare a list of the various versions of the work it becomes increasingly possible to form a feel for it, and this approach is, crucially, based on the notion that the idea can always escalate. The gaze is directed outwards, not inwards. Insofar as one should even put into words what is happening here, it constitutes an opening up of what is often known as ‘black boxes’ within actor-network theory: devices, facts or concepts that we no longer think about, but simply accept as given. Pedersen’s treatment of the exhibition medium invites us to reconsider the concept of ‘art’, but it also shows us the entire conventional set-up of permits and prohibitions in a new light.

The project begins with a plan to arrange an exhibition featuring posters issued by Systembolaget, but it takes form when it becomes necessary to challenge the established notion that an exhibition consists of objects put on display. The project is sent in a new direction by a prohibition: the injunction against using Systembolaget’s materials. The question of what an exhibition is or can be is joined by another theme: the question of who can decide what, how and on whose behalf. After the concept of exhibitions, the next black box to be opened is that of permissions and prohibitions. The difference between problem solving and ‘idea escalation’ as Pedersen understands the term is that the box cannot be closed again. His car guide might have become a new black box, an object with a universally accepted and understood appearance and function, but when we consider the project on the basis of the concept of ‘idea escalation’ it becomes food for thought instead.

And the poster? Perhaps it is fortuitous that it ended up in the National Gallery of Denmark. Within a museum setting it is, simply by being a perfectly ordinary poster without any value as a work of art, uniquely positioned to open up the black box known as ‘art’. Not because it is art, not because it was used in a project that may or may not be described as art, but because it falls outside the established categories found at museums. Just as an invention that neither succeeds nor fails, but wishes to remain uncompleted, is difficult to fit into the category ‘inventions’. ▢

This article was made possible by a stipend for art historical research awarded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, project no. NNF16OC0019724.

Translation by René Lauritsen.

The top image is a detail of fig. 4: Two Home Guard members demonstrating how the trebuchet works, 1976. Knud Pedersen’s private archives, Nærum. Photographer unknown.