Summary

In the late 1970s, SMK (Statens Museum for Kunst – te National Gallery of Denmark) decided to include photographs in the museum’s overall collecting activities within the field of art on paper. Thus, for the past forty years the museum has acquired photographic works by visual artists who also work in other media. The article investigates the kinds of photographs that have been incorporated into the collection and explores the various outlooks, perceptions and artistic treatments of photography they represent. Based on the concept of photography in an expanded field, the article analyses selected works pertinent to key trajectories in the collection: the performative and the theatrical, the materiality of photography, and its optical and illusory effects.

Article

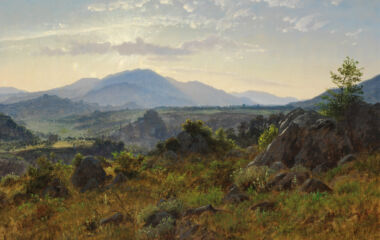

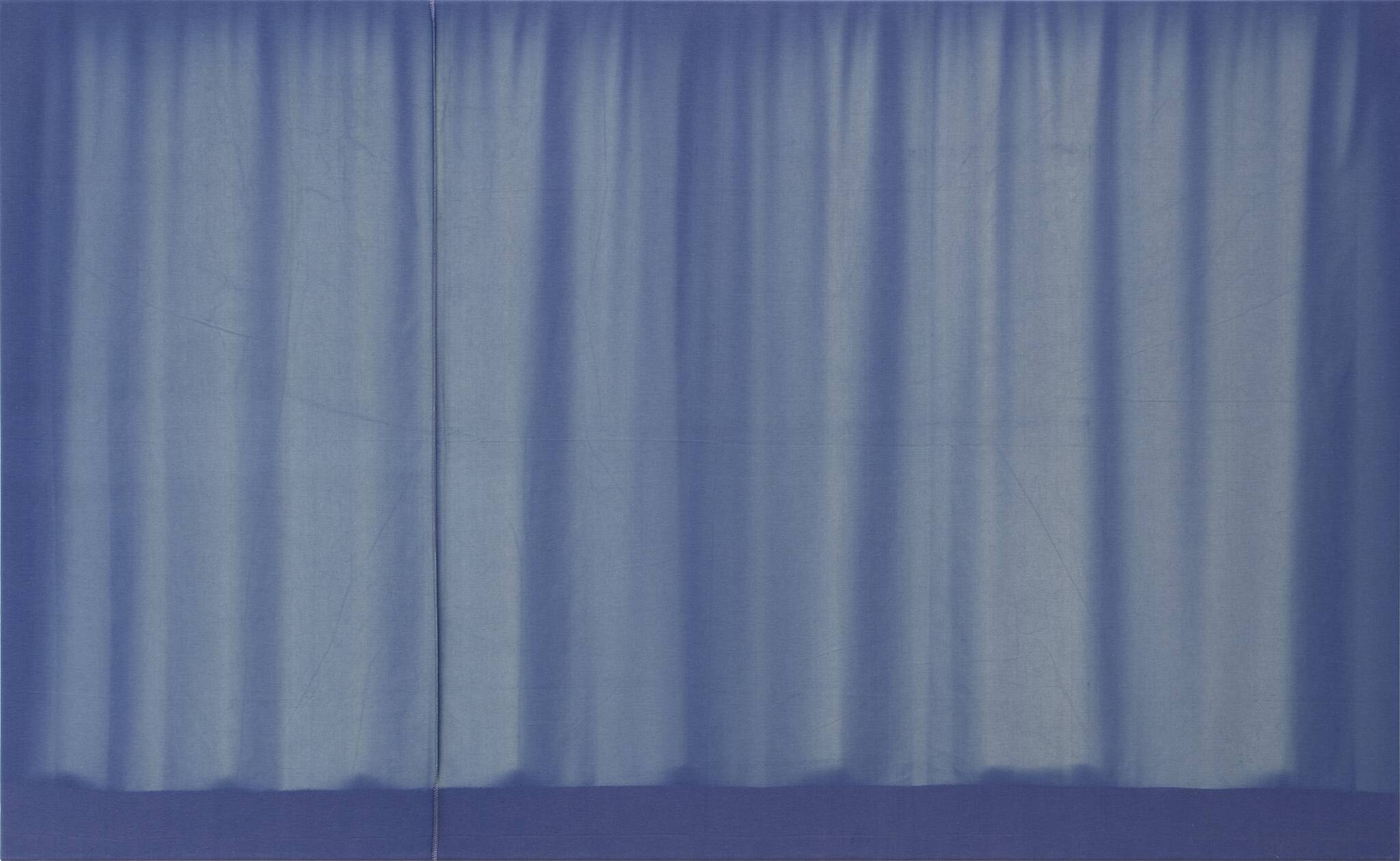

Stills is the title of a work by Marie Lund. Created in 2013, it was acquired for the National Gallery of Denmark in 2020 [fig. 1]. The work comprises three canvases covered with an actual curtain partially faded by exposure to sunlight. The three ‘stills’ appear in different shades of a bluish colour, fluctuating between lighter and darker parts. The picture plane is like a rolling sea created by the folds of the curtain while the sun flooded it with beams of light. Over time, imprints of these folds have caused various degrees of bleaching of the fabric and resulted in the undulating effect of what has now become a stretched-out, flattened picture plane. Few would hasten to call this work a photograph, yet Marie Lund’s choice of title refers to the photographic still: the freezing of time, capturing a given subject in a given moment. In this case, that moment is an extended one, potentially encompassing several years of exposure to light, and it has not been arrested by pressing a shutter button, but by removing the curtain from the original source of light. If one reduces photography to its most basic trait, this work can indeed be reasonably perceived as a photograph: here we find light leaving traces on a surface.

Stills is, then, a work that posits itself between categories, evading firm designations of genre; it looks like a painting, derives its process from the realm of photography and also inscribes itself into a sculptural minimalist tradition. One might say that the work places itself within what has been termed photography in an expanded field, thereby also embedding itself in the interdisciplinary artistic approaches to photography one finds in an institution such as Statens Museum for Kunst. Ever since the late 1970s, photography has been included in the museum’s collection of art on paper. Today, the museum owns well over 1,000 photo-based works by 120 artists, covering a period that extends from the 1960s to the present day, supplemented by a few works from the period 1920 to 1950. At the time of writing in 2023, well over forty years after the museum began collecting photographs, fine-art photography is featured in the museum’s collection and special exhibitions entirely on a par with other art forms. Now is a good time to pause, look back and reflect on the outlooks and perceptions of the photographic medium represented in the museum’s collection.

When the museum first began collecting photo-based works, a decision was made to focus on ‘visual artists who also use photography as an integral aspect of their work’.1 The museum never entertained any ambitions of creating a photo-historical collection, as is also evident from the catalogue for the first exhibition of the photographic collection in 2010, entitled Fotografier (Photographs).2 Here, the curator of the exhibition, Vibeke Vibolt Knudsen, wrote:

Precisely because this collection of photographs is part of a wider art context, one that provides perspectives on art history, its profile is different from that of the collections housed at museums dedicated solely to photography. Artists have often taken a rather more free approach to the camera, adopting a more experimental, perhaps even less respectful position than photographers in general, blurring their focus on photography, as it were. By contrast, photographers have, generally speaking, explored the potential modes of expression in a rather more stringent fashion in relation to the medium’s own discourse and history.3

Such a collecting practice prompts an obvious question: what kind of outlooks and preconceptions of photography have informed and shaped the collection over time? It also begs the question of how visual artists use the medium? As is exemplified by Marie Lund’s work, artists tend to ‘integrate’ photography in their practice, meaning that they do not simply add photography as yet another genre in their repertoire. Rather, it forms part of an overall practice where the boundaries between such genres break down. However, this can happen in many different ways.

In what follows, I will delve into selected aspects of the collection, focusing on six artists. I shall consider various ways in which photography has been interwoven with other art forms: painting, printmaking, sculpture and performance. Throughout it all, something fundamentally photographic is at the heart of the endeavour – light, time and indexicality (reflecting the photograph’s inherent nature as an imprint of a subject), but these aspects are put into play in many ways. Over the course of the article, I will move through works that share a deliberately experimental approach to the photographic image, yet emphasise different elements in their artistic exploration of the medium. Thus, I focus on the performative body and the materiality of photography in the analyses of the first three artists, while experiments with photography’s optical and illusory effects are the mainstay of the subsequent analyses.

Furthermore, I have delimited my selection by highlighting the Nordic part of the collection and confining myself to the period from the 1990s onwards. These choices are due to the fact that the majority of the artists represented in the collection are Nordic, meaning that this part of the collection also reflects a regional development in the period’s artistic strategies pertaining to photography. Photography becomes an integrated part of contemporary art in Denmark in the 1990s, and the period also sees significantly increased collecting activity. Of course, every choice to include something involves leaving something else out, and some aspects of the collection will not be addressed in this article. This applies, for example, to photo-based hybrid works in the collection (collages, assemblages, etc.), activist-oriented photography, and to the snapshot aesthetic – a movement emphasising a certain everyday realism – that is also featured in the collection. My choice to direct attention to the specific artists selected here rests on the very fact that they move on the threshold of photography without rescinding an awareness of the medium’s field of action. This makes them particularly fruitful as subjects of analysis, serving as examples of some of the central discussions about photography’s overlaps with other adjoining media – discussions which the collection at SMK raises by its intermedial focus in the acquisition of photographic works.

Light refractions in the landscape

In 1990, the Greenlandic-Danish artist Pia Arke (1958–2007) built her own pinhole camera. A pinhole camera is a box which does not admit any light – except through a small hole in one side through which light can penetrate. The photographer will usually stand outside such cameras, but Arke built her pinhole camera so big that she herself could sit inside it. She placed richly contrasting black-and-white lithfilm measuring 50 x 60 cm on the back wall, using exposure times from fifteen minutes upwards.4

Arke described her camera in these terms:

While constructing the box, I entertained many thoughts about building an entire little home for taking pictures. My choice to actually do so arose primarily out of a desire to be united with the tool that creates my images.5

Arke used her pinhole camera for a number of works, for example when, in 1990, she took a series of photographs of the view from the place where her childhood home in Nuugaarsuk Point, Narsaq had been. These images later appeared as backgrounds in a number of other works, such as The Three Graces (1993). Usually, pinhole camera images are taken without the operator being able to see exactly what is being captured, because there is no lens through which the selected image and its cropping can be seen. Here, where Arke is able to physically sit inside the box, she is not only united with her tool; she can also influence and become part of the picture itself. With her body, she can shade the light during the exposure, thereby forming outlines of a body and of movements that become shadowy silhouettes in the landscape.

The approach can be observed in, for example, the Kronborg series alias The Kronborg Suite from 1996, which was shot at Kronborg in Elsinore [fig. 2]. The series was acquired by SMK in 2019. The transparent ghostly character of the work creates a very special ethereal and material quality, evoked by the presence of the body in the picture. In The Kronborg Suite, the photographic creative process also becomes a sensuous way of being in the world; a conquest of the landscape which materialises in concrete terms in the production of the image and in the picture plane itself.

In many of Arke’s works, photographs appear in the context of themes such as post-colonialism and gender identity, partly in the form of photographs taken by her and partly via a critically informed use of found photographs from archives and from Arke’s own family history. Readings of Arke’s work have generally focused less on their experimental approach to media and to materialities; traits which can also be found in her practice and which in no way run counter to her critical examination of the codes and language of photography. With the pinhole camera series from Kronborg, Arke also seems to ask how a photographic image can capture and influence the world as we see it? The photographer Marianne Engberg has described the pinhole camera’s transformation of its subject as follows: ‘Waves became flat, people disappeared, clouds became beautiful long lines, pouring rain became a gentle mist’.6 The combination of exposure times and the pinhole camera technique is what conjures up these depopulated, alien and transformed impressions of a reality where everything that moves changes or disappears in the slow freeze of exposure. Engberg’s description can help us understand the sense of looking at an imaginary landscape that Arke evokes in The Kronborg Suite. On the one hand, the image captures a subject located in front of the camera box, one in which parts of the scene, for example the stone pier at the bottom of the picture, stand out clearly and crisply, while other parts are blurred and flicker. On the other hand we see a landscape that only exists or is produced in the image.

As was indicated by Vibolt Knudsen’s description of the collection, quoted in the introduction of this article, the collection activities have had a very specific focus. A systematic review of the photographic collection makes it clear that this stated focus has been adhered to with great consistency. This also means that classic black-and-white photographs and genres such as landscape, portraits or documentary photography are not found in the collection. There are none of the kind of photographs of which the history of photography is so full, and which Pia Arke actively uses in her own practice, subjecting them to critical interpretation and incorporating them directly in the form of found photographs. In this sense, Arke is an example of an artist who engages deliberately with photography’s historical form of representation and discourse.

The pinhole camera was just one way in which Pia Arke used photography in her artistic work. Her investigative and critical use of found photographs and her own production of photographic images constitute an excellent example of the complex practice of photography represented by contemporary art, one which has been addressed by the concept of photography’s expanded field.7 It was George Baker who, in 2005, was the first to theorise on the idea of photography’s extended field, drawing inspiration from Rosalind Krauss’s poststructuralist theory of sculpture’s extended field from 1979. To summarise, Baker proposes that photography in contemporary art should be understood as a result of intersecting media. In his view, photography understood as an independent medium with media-specific characteristics should be replaced by an understanding which sees photography as a mode of image-making that may, for example, be based on cinematographic and narrative elements. Baker finds an example of such a practice in the work of artist Jeff Wall.8 The key to describing and conceptualising photography in contemporary art is, one might say, to understand it as practices in which photographic tools allow themselves to be informed by other media, ranging from the cinematic to the sculptural, within an often-conceptual field. The idea of photography’s expanded field opens up a view of photography as a hybrid form of image, which also implies and requires a different approach on the part of the viewer. If you insist on regarding Pia Arke’s Kronborg Suite as a landscape photograph with documentary qualities, you will be disappointed. This is a series of evocative, mysterious and ambiguous photographs that reject photography as a precise record of a given moment. In the pinhole camera photographs from Kronborg, Arke instead uses light as material in a performative practice rooted in the body. Using relatively simple means, she creates ambiguous images of landscapes that are captured and frozen through the small aperture in the box yet are simultaneously taken over by the body that transforms it, imprints it and absorbs it. Here, a performative and conceptual study of body, landscape and light is combined with an experimental approach to the photographic medium. In Arke, the creation of images while experimenting with light simultaneously becomes a critical rewriting or overwriting of an existing landscape in order to open up our minds to another place, another story. An inherent reflection on the media lies embedded in the gesture when artists like Arke work with the old pinhole camera technology, one which has to do with the slow process of the technique and with light as a material. The pinhole camera sprang from the camera obscura as a pre-photographic technique and vision technology that strove for a precise and accurate representation of its given subject.9

In contrast to this tradition, Arke establishes a landscape where the points by which the eye navigates the scene become fluid, rather like the sea moving with such vibrating energy in the picture. In doing so, she also addresses the act and concept of viewing, both in terms of reading images and in terms of one’s view of the world as something that can be changed depending on the perspective.

Image Theatre

Another example of an artist who established a new photographic aesthetic in Danish photography in the 1990s is Swedish-born Agneta Werner (b. 1952). As in the case of Pia Arke, her work was added to the SMK collection at a late point: in 2017 the museum acquired two photographs from the series she was still life/ reconstructing sense from 1990.10 These are photographs of staged setups, placing us in a different kind of pictorial space than Arke’s pinhole camera photographs. However, Werner’s photographs also engage with the relationship between gaze and observer. In this series and other works, she reflects on photography’s form of representation. As in Arke’s Kronborg Suite, we as viewers cannot be certain what we are facing. Our gaze is catapulted around the scenic space created in the photograph where pedestals, columns and plinths form an architectural framework around everyday objects and photographs. In one photograph, a crystal glass is raised high up in the air on a column that rests on a plinth. The plinth has been painted to look as if flames are licking up its sides [fig. 3]. Elsewhere in the arrangement, a string of beads shaped like a large spider is perched on a pair of apples, and in the foreground two brushes have been arranged on separate columns, bristles pointing upwards. Behind one plinth, the lower part of a woman’s leg pokes out, and from the ceiling hangs a plucked chicken bound up in steel wire with two peeled bananas on top. In the second photograph, a beam containing mushrooms partially blocks our view of the tableau behind [fig. 4]. As in the first photograph, the arrangement comprises a combination of different objects placed on plinths. These include photographs where the figures have been cut out, and at the top we see part of the female body again, engaged in doing something outside the picture frame. As observers, we get the sense that the picture may look completely different in a little while. It is an ongoing process. The character in the picture is doing something – she is lining things up, arranging them, putting them in order, creating a system of some kind.

she was still life/reconstructing sense represents a practice widely found in the collection: a way of working with photography as staging. The artist creates staged setups or fictional situations specifically made to be captured on camera, thereby becoming a pictorial statement. Examples of staging as an artistic approach run like a thread through the entire collection, from Kirsten Justesen’s Circumstances series from 1973 to Sarah Lucas’s staged self-portraits from the 1990s, Anja Franke’s series Labotik from 1996, Elmgreen & Dragset’s series End of Natural Behaviour or Peter Land’s The Lake from 1999.

Overall, the collection is characterised by artists who engage with the borderlands of the photographic, thereby calling keener attention to photography’s interfaces with other media: sculpture, painting, video and performance. Such an approach involves important reflections on the aesthetic effect of photography which can help to redefine or reinterpret traditional art historical genres such as the portrait, still life or landscape, as we also saw in the case of Arke’s reinterpretation of landscape photography.

In this series, Werner grapples with the still-life genre, adding to it an element of something performative or theatrical, set in motion with particular force by the female figure as a potential engine of action. The British photo theorist David Campany believes that photography cannot avoid transforming our surroundings into a world that is performed or posed, even when the subjects being photographed are objects and surfaces.11. According to Campany, photography’s translation of a subject into an image possesses an inherent theatricality, and Werner renders this photographic effect concrete in her tableaux which precisely function as staged set-ups. Her photographic practice emerged out of the postmodernist new (American) photography of the 1980s with a focus on theatrical elements and staging (Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman, Les Krims and so on) and its appropriation of the image culture of mass media (Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, and the like). However, a series such as this refers equally much to Surrealism’s way of combining and juxtaposing surprising elements to shock and prompt greater receptiveness to a new understanding of the world. As professor of photo studies Mette Sandbye states, it would be misleading to call Werner a Surrealist because that term is so closely linked to a specific historical period, but nevertheless Werner uses Surrealist techniques in her evocations of poetic, associative and ambiguous pictorial spaces.12 The absurd juxtaposition in the works she was still life / reconstructing sense evokes associations with the interwar period’s Surrealist photographs of mannequins and everyday objects as well as to the Surrealist window displays created by artists, such as Wilhelm Freddie’s Susanna and the Elders – a display for the Copenhagen department store Magasin du Nord in 1947.13 With her photographic works from the early 1990s, Werner establishes a point of view where Surrealistic shocks are flung in together with a postmodernist sensibility. The result is a pictorial space where any thought of presenting complete and true images has collapsed in favour of a composite experience of reality and image. Much of the staged photography created at the time plays on the ambiguity of photography’s realism by creating such fictional staged situations for the camera by means of costumed people, dolls, masks or other theatrical elements, often aiming to critique established notions of representation by highlighting how the photograph is a construct.14

Werner represents a generation of artists in Denmark who, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, became interested in photography as a visual tool on a par with other vehicles for artistic expression. A generation that did not feel obligated to work within a particular photographic tradition.15 Therein lay a detachment from modernist photography’s self-understanding and outlook on art, which cultivated the idea of the particularly ‘photographic’; including the concept of the photographer’s view of the world and the ‘pure’ photograph, meaning an unmanipulated and unconstructed image. In the 1980s, the art historian Abigail Solomon Godeau identified a clear division in art photography between, on the one hand, a modernist line with its associated photographic self-understanding, and on the other, the postmodernist wave, which was very much defined by visual artists who use photography in their practice.16 This distinction is reflected in the institutional strategy for incorporating photography into the collection at SMK, where it finds its way right into the very rationale for bringing photography into the museum at all: as has been mentioned, the collection focused on artists who practiced photography as part of an overall artistic endeavour. Photography gained increasing prevalence on the contemporary art scene in the 1990s, and this was also the decade when photographic works became a natural part of the collection at the museum and were featured, for the first time ever, in a presentation of works on paper in the SMK collection, specifically in the exhibition A Sight for Sore Eyes II in 1998.17 As regards this definitional demarcation, it is worth noting that most of the artists who have photo-based works in the SMK collection are also represented with works in other media.18 For example, the collection includes three drawings by Agneta Werner from 1987.

A space for floating

The inclusion of photography in the museum also involved the introduction of a new type of image in the art institution, one which is linked to photography’s pathways into the visual arts from the 1960s onwards – and the changes that photography wrought in the realm of art. From the preface to the Louisiana Revy in 1994, one senses that in those years photography was perceived as a medium of crucial importance in contemporary art: ‘Photography has transformed image-making in contemporary art, indeed our entire way of seeing and perceiving images’.19 It is certainly true that the photograph introduces images from, for example, mass-produced media and popular culture. Conversely, the artists’ use of photography also contributes to a change in the photographic image which finds new forms of expression in artistic investigations of the medium closely associated with, for example, performance art and conceptual art. These movements towards the performative and conceptual are also reflected in the collection at SMK, as is exemplified by the aforementioned Agneta Werner and Pia Arke, each in in their own way. Another artist who, from the late 1990s onwards, takes the photographic image into new territories in an interaction between performance, body and sculpture is Sophia Kalkau (b. 1960), who has five works in the collection.

‘The precise and the crystal-clear creates a space where things can take flight: a space for floating, that’s what I’m attracted to. In the consistent and concise work of art there is an opening, a point of entry to the world, to the moment,’20 Kalkau stated at one point, and to my mind this idea of a ‘space for floating’ condenses the sensation of photography being an open and welcoming space capable of nurturing thought and imagination, one which Kalkau’s soberly observant yet enigmatic photographic works can certainly evoke.

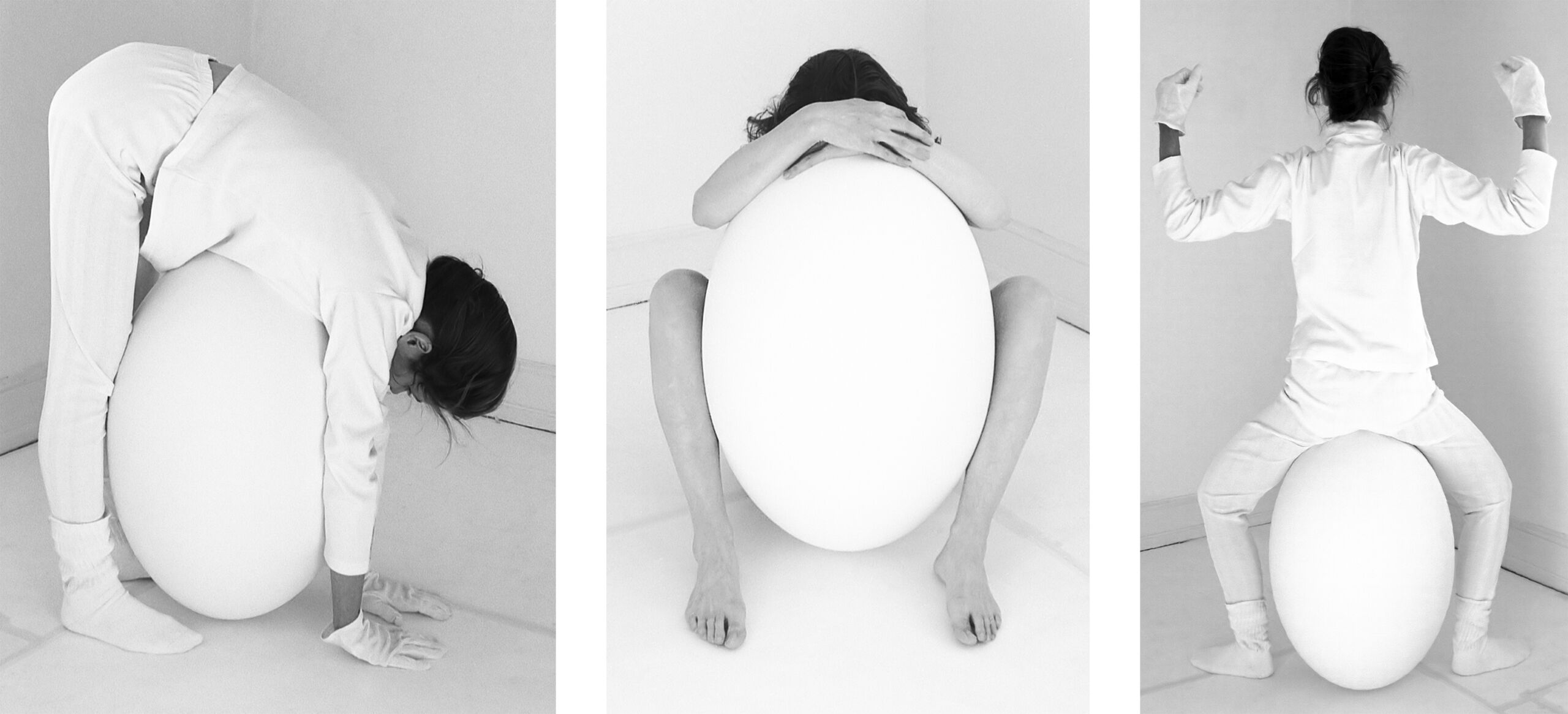

Kalkau works with sculpture as well as photography, and the artist’s practice often involves a dialogue or cross-pollination between the two media. In connection with the exhibition From Hexa to the Vase at the Glyptoteket, Flemming Friborg wrote: ‘In Kalkau’s art the sculptural form is an appearance, a slow coming into being before our eyes. These objects have their very own temporality, which is not easily reduced to form alone’.21 The description might equally well apply to the way in which body and object appear in Kalkau’s photographic visual world, where she herself appears in staged tableaux with geometric objects, and which are best described as a hybrid form poised between photography, sculpture and performance. The earliest work in the collection is Tableau/Eggs from 1999, acquired in 2020 [fig. 5]. In this, Kalkau appears with a large ellipsoid shape, an egg-like sculptural object with which the artist’s body interacts in different ways over the course of three images: holding it, bending over it, sitting on top of it with ‘a scenic presence of body’, as Rune Gade describes the status of the body in Kalkau’s photographs.22 Here we find the insistent presence of a single body, but in most cases the artist’s face is not visible, causing the body to appear impersonal and de-individualised, as Gade goes on to write.23 Kalkau speaks of her photographs as ‘performative’ precisely because of the interaction that takes place between body and object in front of the camera, finding its form in the image.

The British art theorist Margaret Iversen posits the performative in photography as a practice that helps to redefine the image and transport it from the document’s depiction of ‘what has been’ (Barthes’s famous term for the photograph’s reproduction of something that at one time has been in front of the camera) to a more future-oriented and questioning or investigative form of image of ‘what will come?’24 It is, then, about a shift away from the photograph as a snapshot of a given moment towards a type of image that cultivates a different, extended sense of time where repetition and slowness dominate rather than the brief moment.25

Such attention to temporal displacement brings us back to the ‘floating space’ and the kind of aesthetic image-making Kalkau represents with her clean lines and sculptural approach translated to the surface of the photograph – often in series where small shifts in the subject strengthen the sense of the performative gesture inherent in the repetition. The photographs are aesthetic works in themselves, but they are also, as art historian Camilla Jalving has called them, photo-performances in the sense that they document an action.26 In a range of works, Kalkau also takes an experimental approach specific to her chosen medium, working with the photographic technique of solarisation particularly well known from Lee Miller’s and Man Ray’s experiments during the interwar period.27 In contrast to Man Ray’s solarised photographs, in which the figures take on a dark outline, Kalkau’s images are produced digitally and the outlines are bright, even luminous, such as in the work Oh, Sein from 2017, acquired for the collection in 2020 [fig. 6]. Here, Kalkau brings out another type of pictorial space, one which connects the photographic experiments of the avant-garde with a conceptual and digital form of imaging. The performative element remains a mainstay of the work, only coupled with a different kind of obscurity and materiality compared to, for example, the Tableau/Eggs series. But exactly what is smouldering so indeterminately in the work? Some of it arises precisely out of the sensation of an action; the sense that ‘something has happened, can happen, or will happen’, as Jalving describes the effect of Kalkau’s simultaneously sculptural and photographic works.28

By selecting the three artists Pia Arke, Agneta Werner and Sophia Kalkau, I wanted to present three photographic practices that, each in their own way, consciously reflect on the photographic form of representation and use photography to address issues such as the body as a performative gesture, time, light and the materiality of photography. At the same time, they represent a significant trajectory in the collection of feminist and critically oriented artists, which also includes significant works from the 1970s by Lene Adler-Petersen, Jytte Rex, Kirsten Justesen and Ursula Reuter Christiansen. Looking to the 1990s, Anja Franke and Sarah Lucas also merit mention in this context.

Our conceptions about pictures

Our expectations of photographic images are still in many ways closely linked to the idea that a photograph reproduces part of a subject that was in front of the camera at a given time. So says art historian Hal Foster, even as he emphasises that we are also well aware that photography is not and has never been a truthful depiction of reality. We are ‘alert to [photography’s] fictive capabilities’, as he puts it.29 Foster identifies a new aesthetic strategy in artists such as Thomas Demand, specifically in his photographs of models constructed on the basis of existing spaces; these precisely point to the fictional aspects of photography. The approach fosters a new type of realism, Foster believes, one that uses the artificial to make reality real again, by which he means sensible and credible.30 While the description was originally aimed at Demand’s ‘artificial’ reality, the conceptualisation of a new form of realism, one capable of accommodating illusion and fiction, still resonates elsewhere in contemporary photography. And these are strategies that can also be found among works in the collection at SMK, which engage with photography as a space for the senses and thoughts to unfold. Photography’s relationship to reality is an inescapable phenomenon that artists have, throughout the history of this medium, investigated, attacked, experimented with, expanded and taken to the limit.

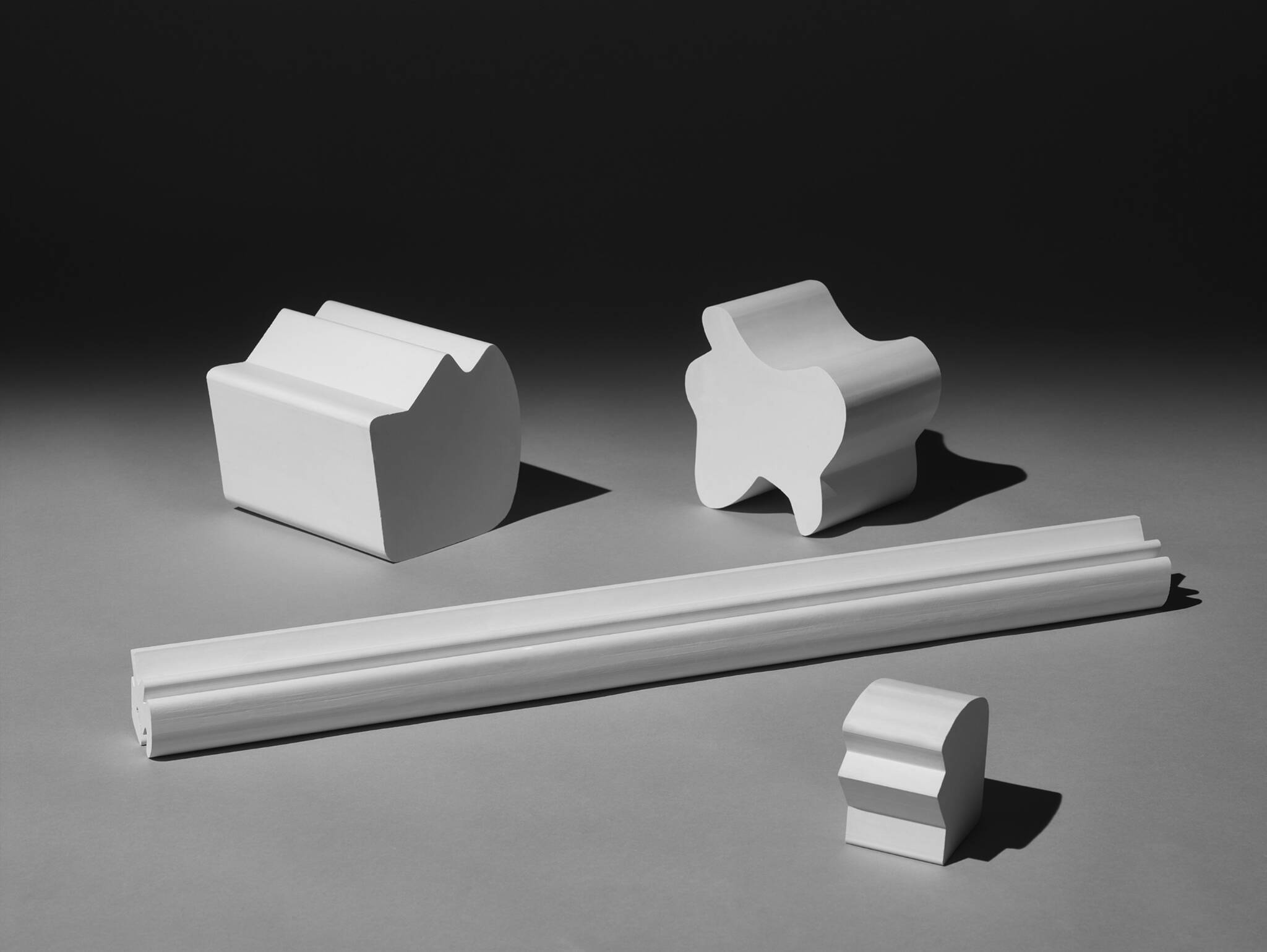

Ebbe Stub Wittrup (b. 1973) has consciously and deliberately worked with photography in an open state poised between document and illusion for many years. Whether working with video, photography, sculpture or installation, Stub Wittrup’s process and art is informed by a conceptual orchestration of a historical, scientific, mythological phenomenon that has set thoughts in motion, awakened a sense of curiosity and nurtured the idea of an enigmatic, open and infinite world. In 2015, six photographs from the series Perception Figures (2015) were acquired for the collection: a series of photographs of white figures photographed against a dark background [fig. 7]. At first glance, the series is a classic study in light and shadow, but upon closer inspection an examination of human visual perception and the phenomena of optical illusions comes to the fore. The series is inspired by the Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin (1886–1951), who in the early 1900s was deeply interested in human perception and perceptual illusions. He became known for his drawing of ‘Rubin’s vase’, which illustrates how we humans distinguish between figure and ground – foreground and background. However, Stub Wittrup’s Perception Figures series is not based on the vase, but on other aspects of Rubin’s studies of our perception of figure and ground in the latter’s Synsoplevede figurer (Visually Perceived Figures) from 1915.31 In drawings of abstract figures in black and white, Rubin investigated how foreground and background can swap places when we look at them. For the series, Stub Wittrup has transformed Rubin’s flat figures into three-dimensional plaster objects of varying dimensions and then arranged them in different positions to photograph them. The seemingly simple arrangements possess a quiet sense of drama. The figures are bathed in light from a special lamp that imitates how the sun emits its rays. The soft light gives the image a greyscale look, adding a very different set of nuances to our perception of the figures. They take on depth, their surfaces come alive, and the dark background and the grey plane on which the figures stand come to resemble a stage. A sense of spatiality is created between the figures, and the photographic surface orients itself towards the spatial organisation of the sculpture. In this sense, the series is also an investigation of how the photographic surface can mimic a spatial experience. The artistic process is closely associated with a conscious use and mastery of photographic techniques. In the series Perception Figures, Stub Wittrup conjures up a hyperaesthetic space where the observer can trace a development towards a greater degree of attention to technical mastery and the possibilities such skills offer in the artistic work with photography as material. A practice that differs from, for example, Agneta Werner’s installations in she was still life / reconstructing sense, which demonstrate less interest in lighting and technical aspects. In the 1980s and 1990s, such a position was also associated with the general revolt against the pure photographic images of modernism.32

A recurring theme in Stub Wittrup’s work concerns his investigation of the photographic medium and exploration of the photograph as image – and as illusion. Although many of the photographs are sober, almost neutral shots, photography’s ability to accurately and faithfully reproduce actual spaces is not the mainstay of Stub Wittrup’s photo-based works. Rather, he focuses on how photography can access an enigmatic space within the realm of the familiar and the recognisable. It can create an illusion of something actual and real which turns out, on closer inspection, to be a result of a tight, carefully constructed and conceptual process. It is about photography as a transformative tool – about how photography translates something the moment you use it. This intersection between something concrete and something imagined is an important piece of the puzzle for anyone wanting to understand Stub Wittrup’s practice with photography. A practice which pushes at our perception of the photographic image as both document and illusion at the same time. It helps to bring us, as viewers, into a space of open-ended, ambiguous meaning, letting us meet the photograph in an open state of mind.

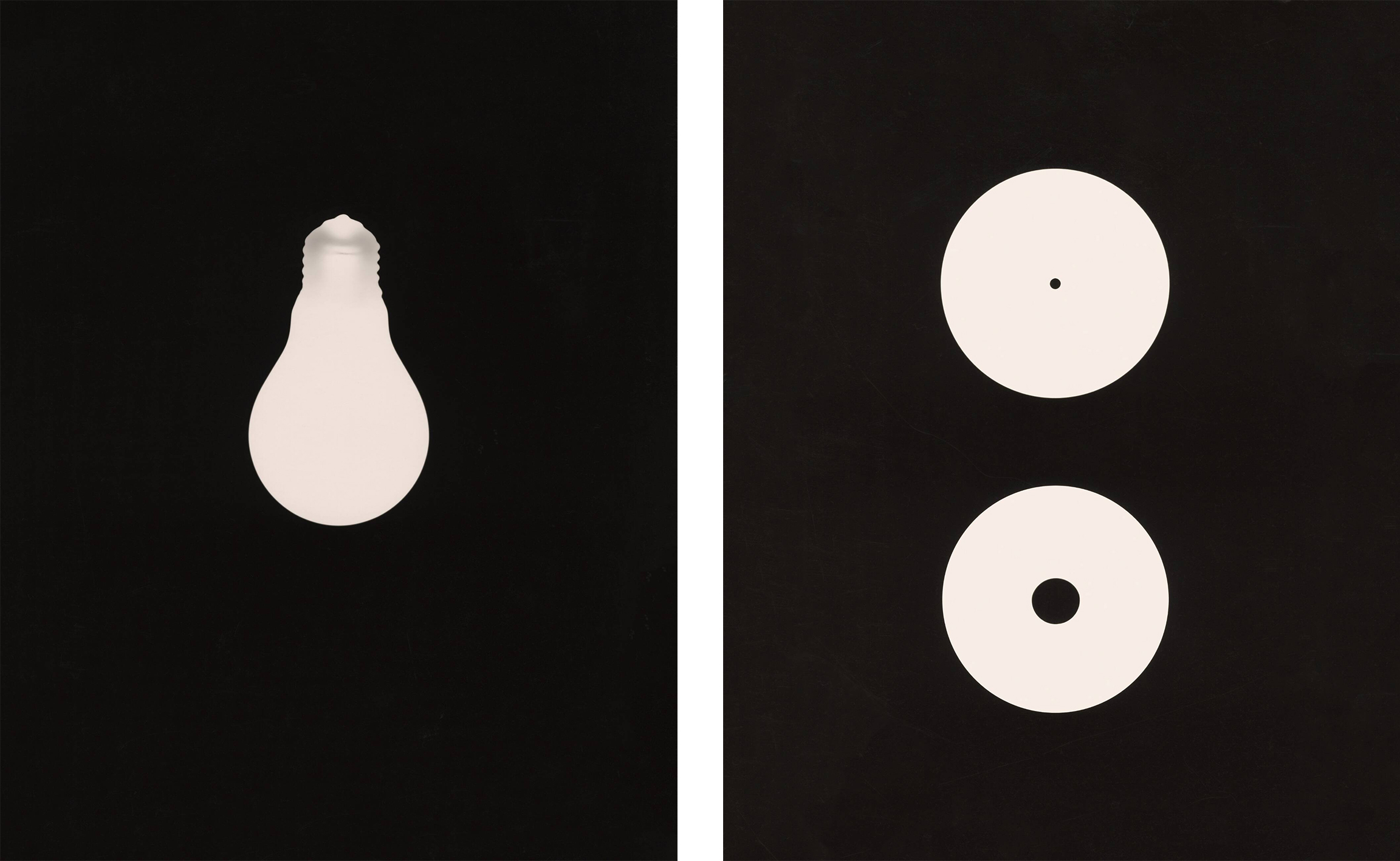

Ebbe Stub Wittrup and Ulrik Heltoft (b. 1973) jointly address photography’s image-making in a different way in the series Index. Created in collaboration between the two artists, the series was donated to the collection at SMK in 2022 [fig. 8]. The series consists of forty photograms, each of which reproduces a darkroom tool used in the process of developing photographic images. On the one hand, the title refers to the series as an index, an archaeological typology, of the components found in a darkroom in an age when the darkroom has been replaced by the computer. In the SMK collection, the work is mirrored by Lene Adler Petersen’s series Diary from the Darkroom at the Eks-skolen Printing Press from 1974. By taking photographs while working in the darkroom, Adler Petersen points directly to the artistic creation of images in itself. On the other hand, the title Index also involves a comment on the medium as such, pointing to the indexical nature of the photograph: the photograph is an impression of a given subject in front of the camera. Krauss has described cameraless photography as having a special ability, as a genre, to emphasise photography’s nature as index,33 and Heltoft and Wittrup consciously reflect on the ontological discussion found in theoretical discourse on the photograph as image throughout the twentieth century.

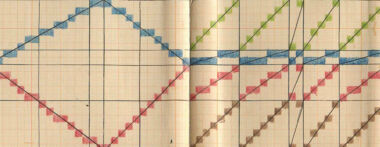

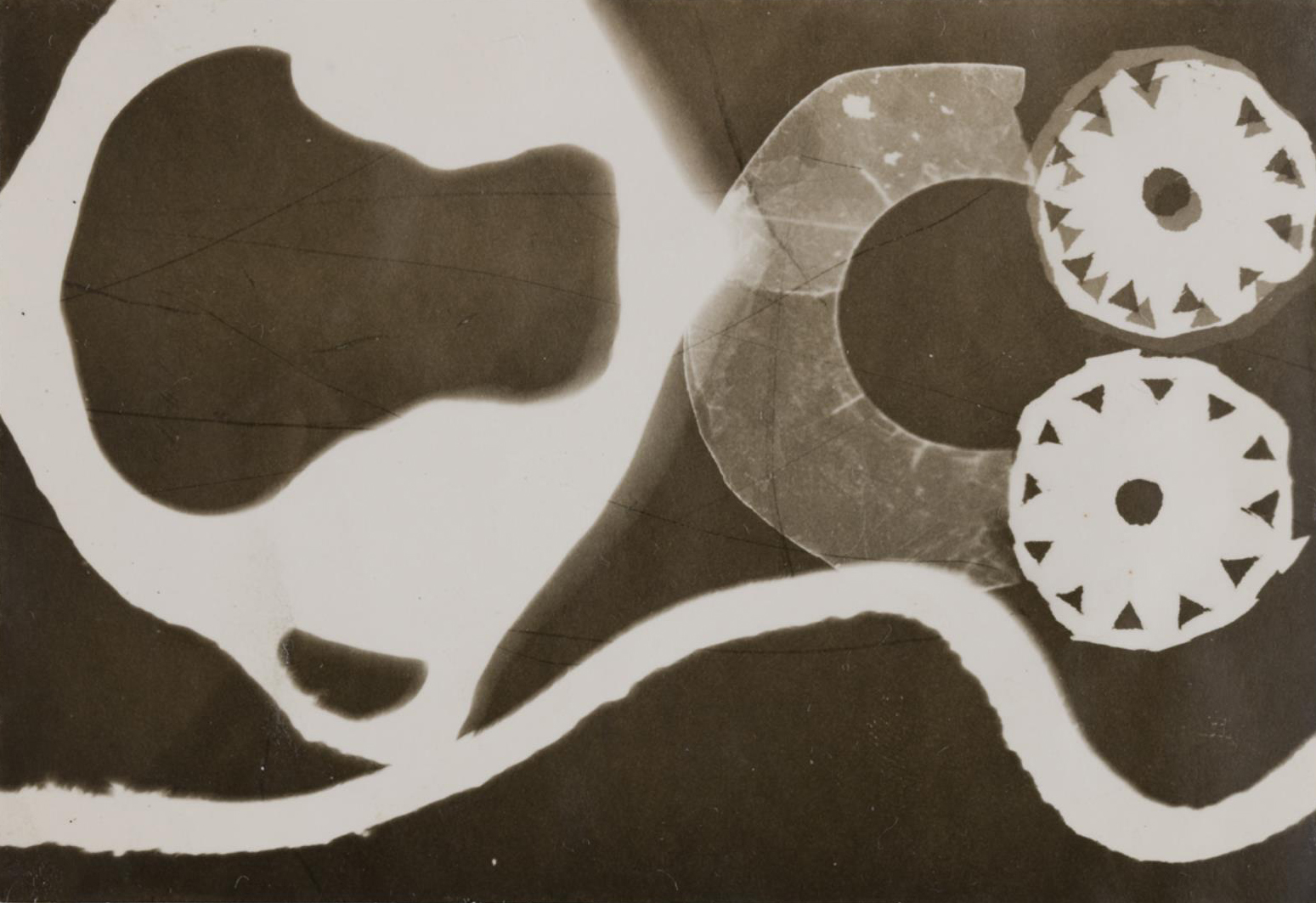

Index also points back to some of the few pre-1960s photographs found in the SMK collection, specifically to photograms created by Albert Mertz and Richard Winther [fig. 9]. In the 1940s, both artists experimented with the unfettered opportunities for creating images offered by the photogram, drawing inspiration from, for example, 1920s avant-garde photography and the Bauhaus school. At that time, these endeavours were about taking a new approach to making images, one which radically reshaped the visual experience and gave the artists the opportunity to create concrete and at the same time abstract-geometric compositions.34 Albeit tentatively, here we see, especially with the recent inclusion of Stub Wittrup and Heltoft’s work, a trajectory in the SMK collection that explores the medium of photography, embracing an experimental practice with photography across time. This aspect of the collection could potentially be strengthened through further, carefully targeted collection activities, ideally supported by research. This area of research is only sporadically described in a Danish context, and collection initiatives augmented by parallel research could contribute to writing a photographic art history extending from the avant-garde in the early twentieth century to conceptual studies of cameraless image-making in contemporary photography today.

Weaving digital images

Moving on from Ebbe Stub Wittrup’s work with the illusionistic properties of photography through accurate, documentary footage, I will explore another type of strategy for expanding photographic image-making. This strategy relies on digital methods to effect a transformation of the image itself, causing another fictional reality to emerge. Here, images that are initially soberly documenting undergo a metamorphosis that dissolves the objectively recording aspect and creates a new type of image experience. Jesper Rasmussen (b. 1959) has worked for a number of years with a digital processing of photographs of architecture where he retouches away all traces of people and human activity, removing windows and doors on buildings and eradicating signs, rubbish bins, traffic and people in urban spaces. The process involves a digital cleansing and visual weaving where Rasmussen closes the ‘holes’ in the image by inserting digital patches from elsewhere in the image. The undertaking brings about a reduction of information in the image that leaves behind empty spaces, simultaneously evocative and eerie. One example is DUMBO, New York from 2005, which was acquired for SMK in 2005 [fig. 10]. The work is part of the series Off Locations, on which the artist has worked for a number of years in Denmark and abroad. Here, the large windowless facades are transformed into an almost abstract composition. The manipulations stay within the realm of the credible, achieving a level of artificiality which certainly makes the subject seem alien, yet does not completely overwrite our belief in the photograph’s accurate representation of reality. Here, Foster’s concept of artificial realism seems once again to highlight the dual effect of realism and fiction created by Rasmussen’s digital weavings. The architecture comes across as empty, closed in on itself like a shell, occupying an intermediate realm poised somewhere between a model and an actual structure. One may also, as Lars Kiel Bertelsen has suggested, say that this reduction of the buildings, showcasing their human-less, unreal yet at the same time very concrete visuality, enacts an eco-archaeological investigation that excavates the houses’ own private lives.35

The advent of digital techniques ushered in a change in the status of photography, and in the early 1990s there was talk of the death of photography. The idea of the post-photographic was introduced, offering a terminology capable of accommodating the new image regime.36 This involved, among other things, a revival of the discussion about the credibility and manipulability of photography, all while bringing with it a renewed interest in photography’s materiality and objecthood. It also paves the way for the creation of new types of photographic images that bring about shifts in our perception of reality and the surroundings of which we are a part. ‘It is important to believe in the image,’ proclaimed Jesper Rasmussen about the Off-Locations series.37 Believing in the image implies that the photographic effect of reality is not completely negated. If the pictures do not have a hook plunged in reality, the unheimlich effect of the alienated and yet familiar urban landscape does not materialise. The collection contains several examples of how artists work strategically with the digital as an extension of the photographic visual language. In the late 1990s, Erik Steffensen (b. 1961) engaged in a reformulation of the landscape image with series such as Arizona from 2000, which reproduces the flat, vast American landscape in harsh tones of pink, or in series of landscape photographs from Greenland and Iceland with titles such as Red Icebergs (1999–2000) or Yellow Volcano (Iceland) from 1998. All three series were acquired for the museum in 2002. In these series he experiments with digital recording techniques, causing the landscapes to appear before us through a digital coloured filter, forming a mirage poised somewhere between a fictional and an actual landscape [figs. 11a, 11b and 12]. Such an artistic approach reminds us that photographs are always also a mediation, an interpretation and a visualisation of the world. In earlier black-and-white analogue series he used a ‘postmodern paraphrasing strategy’,38 looking to art history for subject matter and referring to Danish Golden Age artists and Danish landscape paintings. The later digitally based series are to a greater extent reflections on what constitutes a landscape and our ideas about it. Adopting a media-oriented perspective, the digital approach also inquires into what constitutes a photograph in a digital imaging process. Rasmussen’s digitally manipulated urban landscapes and Steffensen’s atmospheric landscapes are both part of an art historical tradition of depictions of landscapes and urban spaces. Steffensen and Rasmussen use radical digital strategies to reinvent the photographic experience of landscapes poised between the fictional and the actual.

Notes on the photograph in intersecting and expanded fields

I began this article with the blue outstretched curtains in Marie Lund’s work Stills as an example of an art work that borrows properties from painting, sculpture and photography, engaging in a hybrid practice which brings these elements together to form an image in a category of its own. The photo-based collection at SMK was built during a period when the boundaries between media grew increasingly fluid, to the point where we speak of ‘the post-disciplinary’ today. For example, art historian Charlotte Cotton believes that rather than talking about photography, painting and sculpture, one must talk about the photographic, the sculptural and the painterly.39 The majority of artists represented with photographic works in the collection at SMK work across different media, often letting one artistic idiom mix with others, as we have seen in the cases of several of the artists highlighted in this article. However, describing the photographic collection at SMK as an expression of a post-disciplinary state in photography (and contemporary art) would fall short of the mark. Yes, the collection grew out of conceptual art and performance art embracing photography and the inclusion of the medium in the visual arts from the 1960s onwards, but as my selected examples from the collection show, we are also dealing here with artists who consciously reflect on photography as an image form by experimenting with media-specific properties: light, the materiality of the photograph, its indexicality and special relationship with time. I have gathered a number of artists who work across a spectrum of ‘billedtilstande’ – pictorial states – to borrow a term coined by Charlotte Præstegaard Schwartz.40 Each in their own way, they pave the way for new interpretations of what a photograph is and what it means when it enters a collection like SMK’s.

The overall picture forming after a review of my selected examples from the collection from the 1990s onwards is one of a photographic practice that draws on performative and theatrical dimensions and of photography being used in conceptual studies of themes such as perception, body or landscape. To this we may add an inquisitive eagerness to expand the photographic language through media-specific experiments, analogue as well as digital. The fundamental premise underpinning the collection activities (focusing on visual artists who also work with photography) involves an emphasis on intermediality and on the borderlands where photography abuts other media, either because the types of work acquired are hybrid in themselves (in the sense that they mix several media) or are part of a hybrid artistic practice. As we have seen in the above, large parts of the collection at SMK are characterised by photography which, in very direct ways, expands our perception of the photographic image as an expressive image form, presenting entirely different or new types of images. There are definite advantages to applying a focused collection strategy as has been the case so far: in doing so, the museum collects and preserves a branch of the artistic practice of photography which falls outside the scope of the collection activities at, for example, The Royal Danish Library’s picture collection with its focus on the history of photography. Conversely, an unwavering attention to photography in an intermedial or expanded field and a continued insistence on terms laid down in the late 1970s may create a blindness to other types of practices involving photography, both historically and in our present time. It is perhaps more important to look at the practice and the statement made by the work than at whether the creator behind defines themselves as a visual artist or as a photographer. Spurred on by the dialogue that the photographic works in the collection – directly or indirectly – already have with other media, it might be interesting to explore how the photographic dimension can pave the way for new perspectives in the understanding of these other media in the museum’s collections: Can photography and the photographic way of relating to the world and to art help to facilitate other outlooks on works in other media? These questions open up a perspective that is beyond the scope of this article, but they might be important starting points for further research into the expanded field of photography in collections such as the one at SMK.