Summary

The article examines the representation of traumatised man in German art during the period immediately after World War II. The purpose is to offer an outside perspective on the Danish Portrayers of Man (‘menneskeskildrere’) – as represented by Palle Nielsen and Dan Sterup-Hansen, and their images of the miserable human condition as conveyed in the Mennesket (Man) series of exhibitions (1956-1959) – by comparing them to the contemporary German art scene. For more than 20 years after the end of the war, the human figure constitutes what one might call the ‘elephant in the room’ in German art. Not until 1965 did Georg Baselitz embark on his extensive series of depictions of fallen man.

Article

In 1954, the Hungarian-born Jewish writer and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel (1928–2016) wrote his autobiographical novel Night (published 1956), in which he describes his time in the extermination camps Auschwitz-Birkenau and Buchenwald. Wiesel has since stated that in the period up to 1954 he neither spoke nor wrote about his experiences in the concentration camps. For almost ten years, he was afraid of being unable to find words to describe what he had seen. And he feared that the words would lose their meaning as soon as they were uttered or written down.1

Like Wiesel, many others also hesitated to address the traumas of World War II, especially the Germans. Hence, all products of a culture of remembrance, such as literature and art addressing the war, emerged later in Germany than in e.g. Britain, France and Denmark2 – with a few exceptions, such as Wilhelm Rudolph’s (1889–1982) drawings of the ruins of Dresden and Richard Peter Sr.’s (1895–1977) photographs of victims of bombings. When pondering such hesitation, many will be reminded of the German philosopher Theodor Adorno’s (1903–69) famous statement asserting that to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. First made in the essay ‘Cultural Criticism and Society’ from 1949, the statement has often been taken out of context and used to indicate how addressing something so cruel is virtually impossible in a work of art. The fact that Adorno’s intentions were rather more complex is often disregarded as immaterial. For our purposes here, it is interesting to note the way in which so many scholars have read and used Adorno’s statement; it speaks volumes about the pervasive nature of the idea that such mass extinction was too horrific a subject to be addressed in art. While this is held to be true of everyone, it is particularly incumbent on the Germans, who had to relate to their own extreme crimes against humanity.

The Danish Portrayers of Man

In Denmark, artists such as Dan Sterup-Hansen (1918–95), Svend Wiig Hansen (1922–97) and Palle Nielsen (1920–2000) were relatively quick to address the war and its aftermath in works where the human figure takes centre stage. The three artists were the main driving forces behind the exhibition series Mennesket (Man), 1956–59, in which they showed their own pieces alongside works by other artists, all depicting the human condition in the post-war years. In my past research, I have coined an overall designation for them and the other artists who took part in the Mennesket exhibitions, calling them Portrayers of Man, in Danish ‘menneskeskildrerne’ – literally ‘man-portrayers’.3

In an essay written in 1951, Sterup-Hansen emphasised the importance of having art which, first of all, addressed the problems of the age in imagery that is accessible to everyone, including ‘those with little knowledge of art’, and in which the human figure is ‘recognisable and expressed using a wealth of detail that supports our understanding of a given human being and of the significance of said human being in the relevant image’.4 Secondly, artists should not lose themselves in discussions about the exact direction that progressive artistic modes of expression ought to take, thereby ‘washing their hands’ of the matter, treating the soot from the crematoriums as ‘a mere beauty spot’.5 According to Sterup-Hansen, one ought instead to ‘seek a new foundation for culture, seek nourishment and power in the real problems of the age, resolving them in close contact with those who will not and cannot ignore the warning signs’.6 Sterup-Hansen’s text was a response to an essay by Ole Sarvig (‘Kunstens øst og vest’, Information, 15 June 1951), in which he claims, according to Sterup-Hansen, ‘that the human figure can only be implemented in art through the intercession of a greater authority’, meaning that it must be brought about by politically governed socialist realism. For our purposes here, I shall not discuss Sarvig’s text and position, but will restrict myself to exclusively address the discussion on the human figure in art prompted by the essay. In another text written that same year, Sterup-Hansen states: ‘I speak for myself, and I have read no heavy tomes or scholarly accounts, but I live in this day and age, and the problems I face are the same that every other living human being faces. The facts of the war, the facts of the post-war era. Who can shake them off, and who wants to shake them off?’7 Sterup-Hansen believed that it was crucially important to face the recent historical events, addressing them in images where the human figure took centre stage, thereby contributing to rebuilding faith in mankind and in human culture.

At the time, fellow artists Nielsen and Wiig Hansen shared Sterup-Hansen’s belief that the human figure was central to art that wished to depict the reality in which they found themselves. In 1956, this prompted the three men to arrange the exhibition Mennesket at Clausens Kunsthandel in Copenhagen. At the exhibition, the artists displayed works that addressed, each in their own way, what Wiig Hansen called ‘an unhappy time for mankind’ in a later interview.8 The show also included contributions by Henry Heerup (1907–93), Erling Frederiksen (1910–94) and Reidar Magnus (1896–1968), and the six artists would go on to arrange another two exhibitions sharing the same title and held at the same venue; these took place in 1958 and 1959. The exhibitions attracted a great deal of attention in the press and in cultural journals such as Hvedekorn; they were regarded as significant entries into the general discussions about the crisis of humanity in the post-war era and in the current, quite heated, discussions on the purpose and proper form of art.9 The artists’ use of the human figure was seen as choice rich in implications. First of all, it implied a willingness to accept a responsibility towards real life, to get involved with the current times and to meet their expectations regarding art’s obligation to tell ‘the truth’ about current issues, thereby fulfilling art’s role as a medium for insight. The latter was, according to leading cultural figures such as H.C. Branner (1903–66) and Ole Sarvig (1921–81), sorely needed.10 At the same time, the choice of depicting the human figure was regarded as an active espousal of what was generally referred to as ‘content’ in art and as a rejection of what the artist and art critic Jens Jørgen Thorsen called ‘the general trend towards aestheticisation and plagiarising’.11

As indicated by the Thorsen quote, the post-war debate on the choice of artistic expression was extremely polarised; in several ways it reflected the political crisis of the period, particularly the ideological war between the East and the West. The Portrayers of Man went against the dominant trend towards abstraction, focusing instead on the ‘dangerous’ depiction of reality, which, if one were so inclined, could easily be associated with Socialist Realism and thus with a state-ordained, restricted mode of expression. However, as I have argued before, the Portrayers of Man’s narratives of human bodies and their relationships with their environments represent a new form of realism that has strongly Modernist features, including an insistent emphasis on surface and plane and on the compositional structuring of space that is far removed from Socialist Realism.12 This new mode of realism reintroduces man, human emotions and familiar reality, becoming firmly established within 1950s Danish fine-art printmaking with the Portrayers of Man as key proponents of the style.

Purpose, background and method of this article

The purpose of this article is to compare and contrast the Danish Portrayers of Man, as represented by Dan Sterup-Hansen (1918–95) and Palle Nielsen (1920–2000), with their German contemporaries. This is the third article in a series of studies which focus on considering the Danish Portrayers of Man in an international context. In the first study, I compared and contrasted the Danish Portrayers of Man with the British ‘Geometry of Fear artists’, a group of British sculptors who carved out their reputation with the exhibition New Aspects of British Sculpture, presented as part of the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1952.13 The second study in the series drew parallels between the artists involved in the Mennesket exhibitions and the famous American photo exhibition The Family of Man, which first opened at MoMA in 1955 and then proceeded to go on an extensive world tour.14 In both cases, analyses of exhibitions form the basis for an analysis of how the Danish Portrayers of Man depicted post-war life compared to contemporary trends abroad. Examining the history and reception of the exhibitions under scrutiny, these studies inscribe themselves in a broader series of scholarly work undertaken in recent years, described in several contexts as ‘Exhibition histories’.15 Just like the first two studies, the present article addresses an exhibition staged in the past which cannot be visited or otherwise experienced directly any more. Similarly, the historical context has changed greatly from the time the original exhibitions were staged to the time they are now being interpreted. As a result, the exhibitions will be analysed on the basis of surviving materials still available to scholars today, such as exhibition catalogues and photographic installation views, and the article will seek to foster understanding of their contexts on the basis of reports and reviews while also incorporating other literature which offers insight into the conditions and discussions pertinent to the times considered.

The starting point of this article was a desire to consider the Danish Portrayers of Man exhibitions in light of a German exhibition undertaken around the same time and with a comparable theme and focus, namely figurative works that address the post-war human condition through depictions of human figures – an in many ways controversial subject at the time. Because of its particular role as the nation responsible for the genocides of World War II, it is essential to include Germany in this field of study alongside representatives of the Allied Forces (in this case Britain and the United States) and of the occupied nations. The most obvious choice of exhibition in this context is the famous Das Menschenbild in Unserer Zeit, held in 1950 in Darmstadt and accompanied by a seminar, Darmstädter Gespräch, based on the subject of the exhibition.

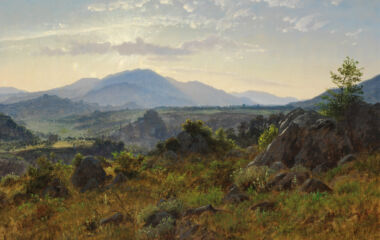

As will become apparent, it turns out that depictions of trauma are largely absent from that exhibition. I have therefore chosen to supplement my exhibition history analysis with an analysis of Georg Baselitz’s (born 1938) so-called Hero Paintings, which are, even though the series dates from 1965-66, one of the earliest examples of a German artist undertaking to address, in a larger body of works, the traumas of World War II in figurative works centred on the human figure. [fig.1] Gerhard Richter’s photo paintings from the same period – such as Uncle Rudi from 1965, where he reuses motifs from World War II photographs – might have been included as an alternative to Baselitz.

My choice to focus on an artist who worked figuratively at the time, using the human figure as a central element in paintings, drawings and prints, rests on the fact that this position was particularly controversial in the post-war period, prompting a range of discussions different from those caused by abstract art. It should not be taken to imply that one cannot find examples of abstract art (as well as media other than the two-dimensional) from the same period which address and process trauma. Asger Jorn (1914–73) and several other artists of the CoBrA group were interested in depicting the animalistic as a symbol of a lost nature, but also, as art historian Hal Foster has pointed out, as testaments to the ‘denaturalisation caused by both World War II and the Holocaust’. As Foster points out, Jorn in particular captures ‘this insurmountable pain’ in works featuring ‘human animals’, such as the painting Wounded Beast II (1951).16 Similarly, artists such as Roberto Grippa (1921–72), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968) and Gianni Dova (1925–91), all from Italy, as well as fellow Italian Enrico Baj (1924–2003) and his Arte Nucleare group and indeed American artist Jackson Pollock (1912–56) can be counted among the many abstract artists whose works responded to the miseries of World War II, either in terms of their subject matter or in their form.17 Joseph Beuys (1921–86) is one example of a German sculptor who engaged with this trauma within sculpture, specifically in his Auschwitz Vitrine from 1956-64.

Incorporating Baselitz’s Hero Paintings means that the article’s method of analysis will undergo a shift, moving away from an exhibition analysis to work analyses that focus on the treatment of post-war trauma depicted in figurative works with the human figure taking centre stage.

In order to set up a frame of reference for the analyses to come, we will begin with a brief introduction to the German art scene in the immediate post-war era.

The Long Silence: The German post-war art scene

Among those who, like Elie Wiesel, hesitated to grapple with memories of war, we find most of the artists of Germany. As stated by art historian and curator Stephanie Barron in the exhibition catalogue Art of Two Germanys. Cold War Cultures from 2009, the German artists generally preferred to address the present rather than the past.18 Referencing the German psychoanalysts Alexander (1908–82) and Margarete Mitscherlich (1917–2012) and their book Die Unfähigkeit zu trauern: Grundlagen kollektiven Verhaltens from 1967, Barron points to how the widespread amnesia among the Germans described in the book also afflicted the artists, prompting them to avoid creating images that evoked the immediate past. In their famous book, the Mitscherlichs offer an explanation, based on psychoanalytical thinking, of why the first many years after the war saw a widespread tendency in Germany – in fields ranging from politics to new construction projects – to repress and remain silent on the grief, guilt and trauma of World War II.19 They also explain how German society’s lack of impetus to delve into its Nazi past was, among other things, associated with the fact that such awarenesses would impede the economic growth already underway at the time.20

In the same exhibition catalogue, art historian Sabine Eckmann also describes the tendency to focus on the immediate present.21 She points out that in the years following the war, art was perceived as a central element of the effort to rebuild a national identity and she describes the paradox inherent in the parallel thus drawn to the politics of the Third Reich, from which the artists were obviously eager to distance themselves. On the one hand, the period saw a widespread, historically informed mistrust of close links between art, politics and national identity, but on the other hand German critics, artists and art historians saw art as an indispensable tool in the reconstruction and rehumanisation of a unified German nation.22

Thus, much of the post-war discussions about art in Germany focused on how art could distance itself from representation, which was associated with the Third Reich, while also finding a mode of expression that could embody and express the new German nation, its mentality, self-understanding and identity.

In the catalogue for Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic 1945-1965, an exhibition of sweeping scope about the post-war art scene arranged in 2016 by Haus der Kunst in Munich, art historian Yule Heibel explains the tendency for German art to distance itself from figuration by stating that the German artists felt it necessary to turn their backs on everything that bore traces of physical humanity because Nazism had destroyed any faith in man.23 Instead, the artists sought refuge in the idea of Geist, which was regarded as immutable, whereas humanity had proven itself capable of changing fundamentally and in fateful ways.24 Geist and absolute abstraction came to form a kind of safe haven, partly in relation to the post-war processing of trauma, and partly in relation to the tensions of the ongoing Cold War. Heibel explains:

’Absolute’ abstraction, which eliminated the body, was the safer bet. As Cold War deepened and the safe as opposed to the experimental set the agenda, it became even less desirable to venture into vitalism, or to see differences within abstraction. Expression and affect were hot-button issues in postwar Germany, especially for people who had expended as much vehement feeling as the Germans had on Hitler and his racial war. Surely German ‘wildness’ was dangerous. A return to that other German tradition of Geist, on the other hand, offered a safe harbor.25

As Barron, Eckmann and Heibel have all established, German artists seeking to find their own mode of expression in the post-war period were navigating in shark-infested waters. During the first many years after 1945, it became imperative for German artists to distance themselves from the past and establish a new vein of German art that was by no means figurative or reminiscent of realism; rather, it must be abstract, speaking into an international context.

German exhibitions in the immediate post-war years

Neither the many taboos which left the Germans unable to mourn their own and their compatriots’ crimes, nor the extreme violence and total destruction caused by the Nazi regime held back the Germans from arranging art exhibitions soon after the end of the war. According to Eckmann, Berlin alone was the site of around seventeen public and six private art exhibitions in the second half of 1945, and the city hosted twenty-eight public and thirty-three private art exhibitions in 1946.26

Many of these exhibitions were solo shows featuring artists who had been subjected to Nazi censorship, such as Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884–1976), focusing on German Expressionism as it had been established prior to World War I. Thus, the exhibitions obviously celebrated art’s newfound freedom, but rather than new pieces they displayed works produced years before.

In several cases, new works by younger artists such as Hans Uhlmann (1900–75) and Willi Baumeister (1889–1955) [fig. 2] were exhibited alongside the older, Expressionist works, and as Eckmann points out, these exhibitions sought to forge ties between German Expressionism and the latest art. She explains:

On one hand, the newly established bond between German expressionism and contemporary practices demonstrated a reconnection to artworks of the past that during the Third Reich had been devalued on the basis of alleged internationalism, distorted renderings, and excessively subjective mark making. On the other, months after Nazi Germany’s surrender, expressionism was also employed to connote contemporary artworks as carrying on a better German tradition, and hence solidifying a new national art.27

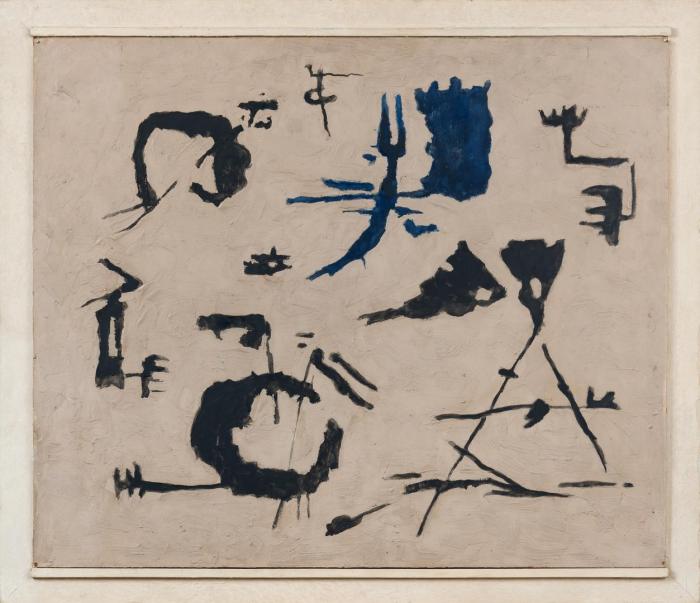

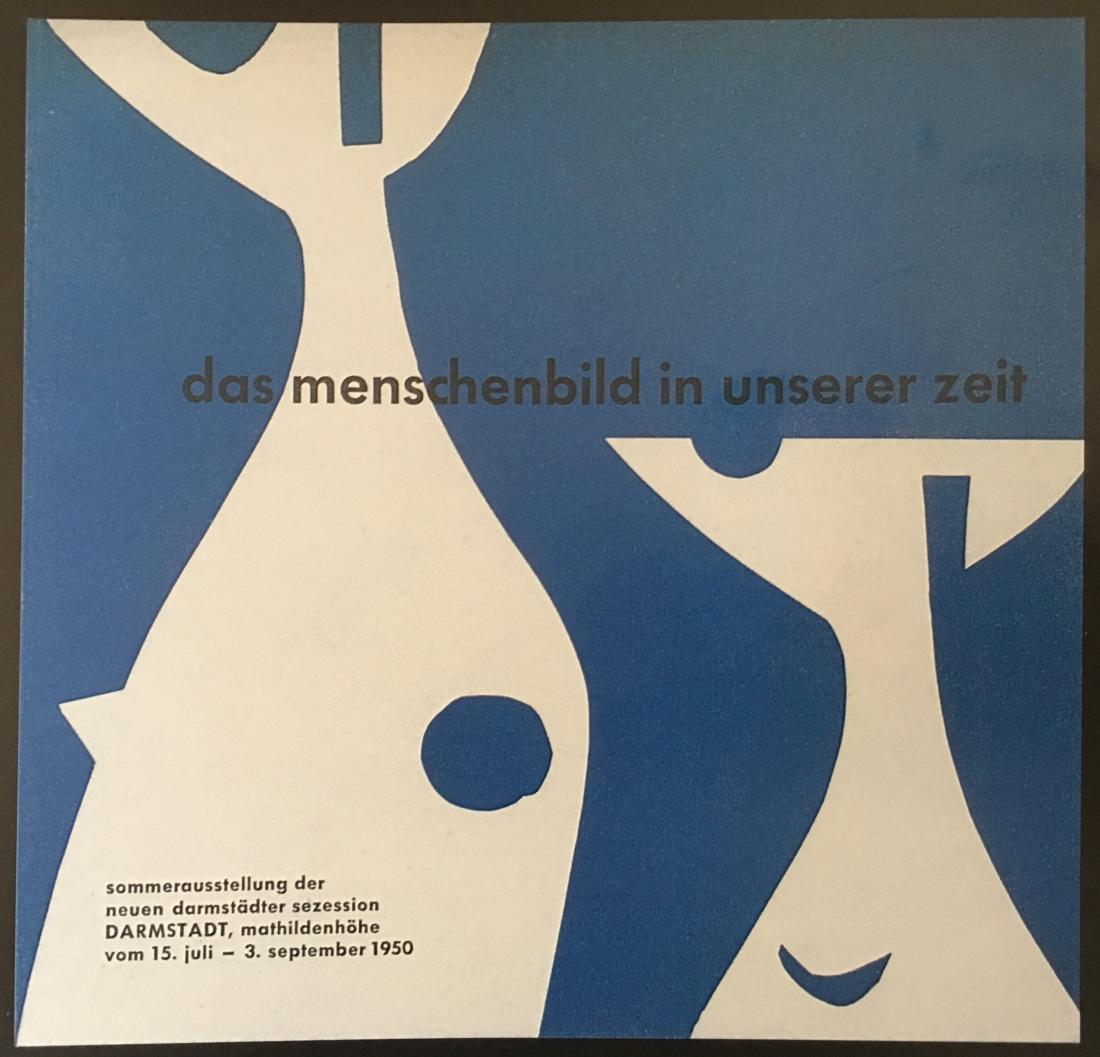

Das Menschenbild in Unserer Zeit

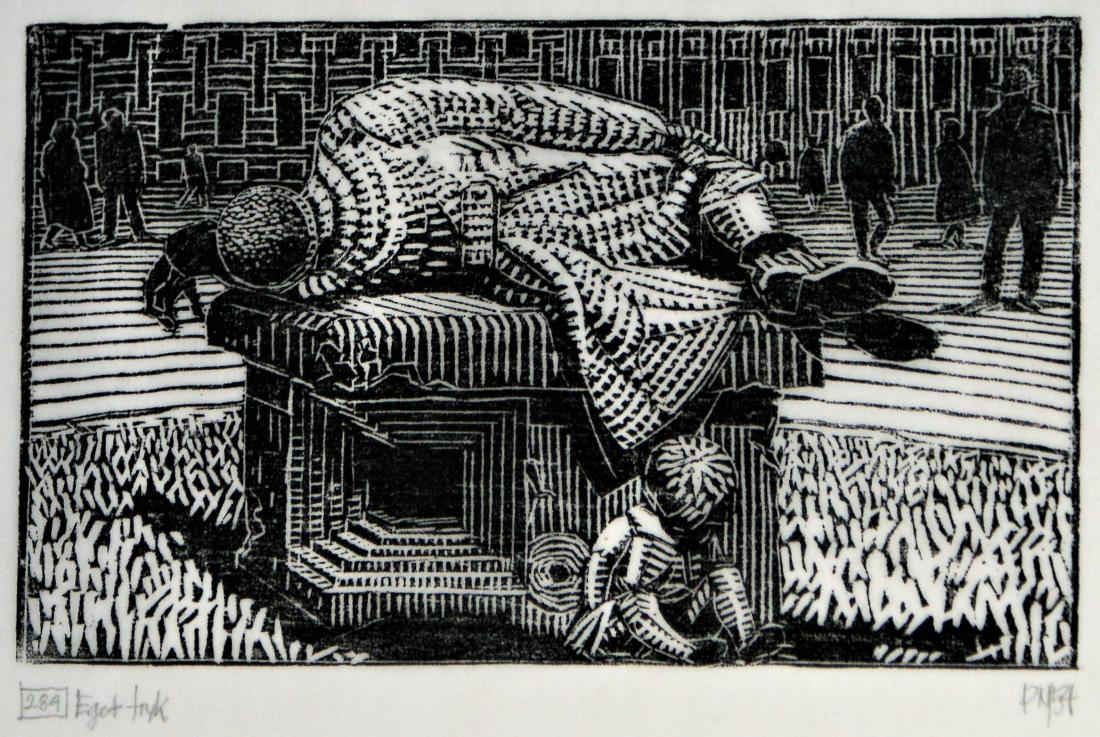

As indicated above, one of the key exhibitions from the early post-war years relevant to our theme is the comprehensive Das Menschenbild in Unserer Zeit, shown in Darmstadt in 1950. [fig. 3] Arranged as the annual summer exhibition of the artist association Neue Darmstädter Sezession, the show presented 205 works by ninety artists, including Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), Max Beckmann (1884–1950), Willi Baumeister, Johannes Itten (1888–1967), Gerhard Marcks (1889–1981) and Toni Stadler (1888–1982).28

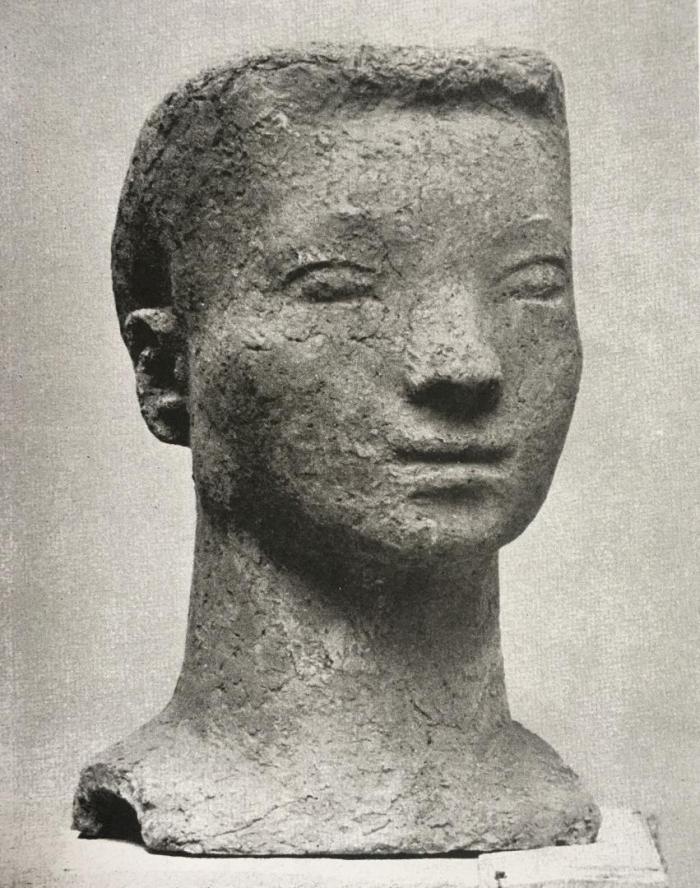

Originally conceived by the young sculptor Wilhelm Loth (1920–1993), the exhibition strove to provide an overview of contemporary German art by presenting a range of different artistic treatments of man as subject matter, including the various degrees of abstraction employed by the artists of Germany at the time.29 [fig. 4]

Accordingly, the hottest topic of the time, ‘Man’, now stood at the heart of an effort to encapsulate the state of German art in 1950. In keeping with this approach, the human figure is a central element in virtually all the works featured in the exhibition, most of which are paintings and sculptures.

In the preface of the catalogue, the association’s chairman Kurt Heyd suggests that themed group exhibitions are particularly well suited to explaining ‘the development and impact of significant cultural issues’, pointing out the exhibitions Der Blaue Reiter and Die Maler am Bauhaus at Haus der Kunst in Munich in 1949 and 1950 and the exhibitions Die Malerei des Expressionismus (1920) and Der schöne Mensch in der neuen Kunst (1929), both held in Darmstadt, as particularly exemplary in this regard.30 In so doing, Heyd makes the same connection between post-war art and German Expressionism described in the above as a pervasive undercurrent in the creation of a new German mode of expression. The link between present and past also informs the selection of works, which date from around 1916 (several works are not dated and may have been produced earlier) to 1950.

While the exhibition title in itself lends itself equally well to being read literally, as in ‘pictures that represent people’, and metaphorically in the sense of ‘pictures that deal with our current perception of man’, the works selected seem to veer mostly towards a literal reading of the title. Looking through the thirty-two illustrations in the catalogue, it is striking to note the extent to which the works evade the period’s most dominant historical event, namely the war, its aftermath and the subsequent need to restore faith in humanity. Instead, the exhibition was dominated by rather classic representations of man and by works that, in terms of content, seemed unaffected by the pervasive crisis. Some works strike a serious note that seems to point rather more towards the recent disasters. These include Georg Heck’s (1897–1982) woodcut Letze Station (undated), Gustav Seitz’s (1906–69) bronze sculpture Gefesselte from 1949 and the former Bauhaus artist Gerhard Marcks’s bronze sculpture Bademeister from 1947. The latter may be interpreted as a reference to the so-called ‘bath attendants’ of the extermination camps, although the figure’s nudity could indicate that it is in fact one of the victims. Hans Kuhn’s (1905–91) painting Gefangene also addresses a subject that might relate to war. However, none of these directly address the war or the memories of it.

While some of the works are sombre in tone, the exhibition as a whole seems more like a quite neutral inventory of the representation of man in art rather than as an exhibition calling for discussion on the human condition. Insofar as the exhibition discusses anything, it focuses on the form and style of representation, not on the crisis of humanity. The same applies to the discussions at Darmstädter Gespräch. This trend is also evident in the contemporary reception of the exhibition and seminar, which attracted a great deal of attention from local and national media alike. Darmstädter Echo, Frankfurter Allgemeine, Die Zeit, Stuttgarter Zeitung and Welt am Sonntag, Hamburg are just a few of the newspapers that wrote long articles on Das Menschenbild in Unserer Zeit. Strikingly, they use almost all of the space allotted to report on and discuss the seminar. Only a few articles deal with the content of the exhibition. One of these exceptions is the author Kasimir Edschmid’s (1890–1966) article in Welt am Sonntag, Hamburg. Edschmid chastises the exhibition for not having made a choice between either abstraction or representation, opting instead to cover everything and thereby failing to fully represent either mode of expression. He also believes that the theme is imprecisely phrased as well as ‘inflated’ and ‘thoroughly literary in nature’, and he regrets the exhibition’s failure to incorporate other approaches, such as social or philosophical aspects. Comparing it to an Italian exhibition also on at the time, he concludes, with some resignation, that ‘Wahrscheinlich ist die Darmstädter Austellung und ihre Devise aber typisch für den deutschen […]’ 31 (‘Apparently the Darmstadt exhibition and its approach is typical of the Germans’)

One may see Edschmid’s description of the exhibition as ‘literary’ as a confirmation of Barron’s, Eckmann’s and Heibel’s diagnosis of the German art scene in the post-war period. The exhibition seems to give a wide berth to subjects and modes of expression that might be perceived as politically charged, just as it avoids exhibiting real, carnal and ugly bodies with visible physical or mental scars. The exhibition thus represents the wilful disregard for reality to which the Danish Portrayers of Man react so strongly in their Mennesket exhibitions. The German and Danish exhibitions do, however, agree on one point, specifically that of the struggle between abstraction and realism. Neither of them chooses a side, opting instead to put the entire field forward, showcasing its full range.

By contrast, form was the focal point of the discussions conducted at the seminar associated with the exhibition, Darmstädter Gespräch. Here, leading intellectuals such as artist and professor Johannes Itten (1888-1967) and professor of art history and former member of the Nazi Party Hans Sedlmayr (1896-1984) came together to discuss representations of man and the changes seen within that field. Essentially, this was a discussion for or against abstract art. The debates, reproduced in a book sharing the same title as the exhibition, included contributions by the philosopher Theodor Adorno.32

The one contribution to the seminar that seems to have generated the most discussion was Hans Sedlmayr’s ‘Über die Gefahren der modernen Kunst’ (Concerning the dangers of modern art). Here, Sedlmayr presented the formal distortions of reality seen in modern art as proof that man has lost his direction, his soul, and as evidence of a ruined world characterised by chaos. He claimed this as proof that modern art was a failure. According to the book, where the audience’s reactions are noted in the margin next to the presentations themselves, this prompted loud shouts of outrage, including ‘Heil Hitler’, as well as tramping, catcalling and so on. According to artist and art historian Philipp Fehl’s (1920-2000) review of the book, the response was reminiscent of the cries heard during a bullfight.33 Fehl sums up the discussions heard in the subsequent days as follows: ‘In toto one can find collected here all the reasons the various factions of modern art ever have advanced to prove their legitimacy’.34 UIn addition to artists and art professionals, the seminar also attracted participants from other disciplines, including theology, medicine and biology, but as Fehl points out, none of these representatives from other sciences managed to add anything significant to the art debate: ‘There were no cat calls as each speaker, with scientific objectivity, involuntarily demonstrated the remoteness of his discipline from the world of art’.35

The discussions heard at Darmstädter Gespräch on whether or not abstract modes of expression were able to represent human content pervades the bulk of the press coverage of Das Menschenbild in Unserer Zeit. The fact that the exhibition subsequently gained a place in art history seems to be much more attributable to the seminar and its famous participants than to the exhibition itself and its stocktaking of the depiction of man in art. Viewed from our present-day vantage point, almost seventy years hence and based on the exhibition catalogue and the reviews mentioned, the exhibition seems an uncritical appendix to the seminar, demonstrating that at that time German art was still processing the Nazi era’s political use of art, that German artists were in the midst of a discussion about which modes of expression may be used, and not least that by this point, portrayals of the human condition of crisis had not yet found their way into the studios of German artists, neither in terms of content nor form.

At first glance, it seemed likely that the Das Menschenbild Unserer Zeit could be seen as a precursor and counterpart to the Danish Mennesket exhibitions, but closer comparison seems rather to highlight a number of differences between the art scenes of the two nations in the immediate wake of 1945. The most significant difference is that the German exhibition largely avoids serious issues that might smack of war and trauma, in terms of content as well as formally. Such topics include war’s impact on man, physically as well as mentally, and on our perception of humanism. By contrast, themes of this kind are central to the Danish exhibitions.

Twenty years later

Not until the 1960s do we see the emergence of German art that truly depicts the traumatised human being as figure and content, and which takes a stand on the human condition after World War II. Baselitz is one example, but other artists also embark on the subject and on treating the human figure around the same time, including A.R. Penck (1939–2017), who, like Baselitz, deals with the situation of a divided Germany. However, Penck’s schematic figures are far less physical, less corporeal, more reminiscent of symbols of man than Baselitz’s figures, which actually appear to be of flesh and blood. Other artists who addressed the subject include Markus Lüpertz (born 1941), Sigmar Polke (1941–2010) and Gerhard Richter (born 1932). As John-Paul Stonard has pointed out, all of the above artists had a past in East Germany.36 For Baselitz, this past crucially influenced his choice of a representative mode of expression; a point to which I shall return.

Baselitz was the first among the German artists mentioned here to truly delve into the trauma of World War II; he does so in a series of figurative depictions known under the collective designation ‘Heroes’ or ‘Hero paintings’.

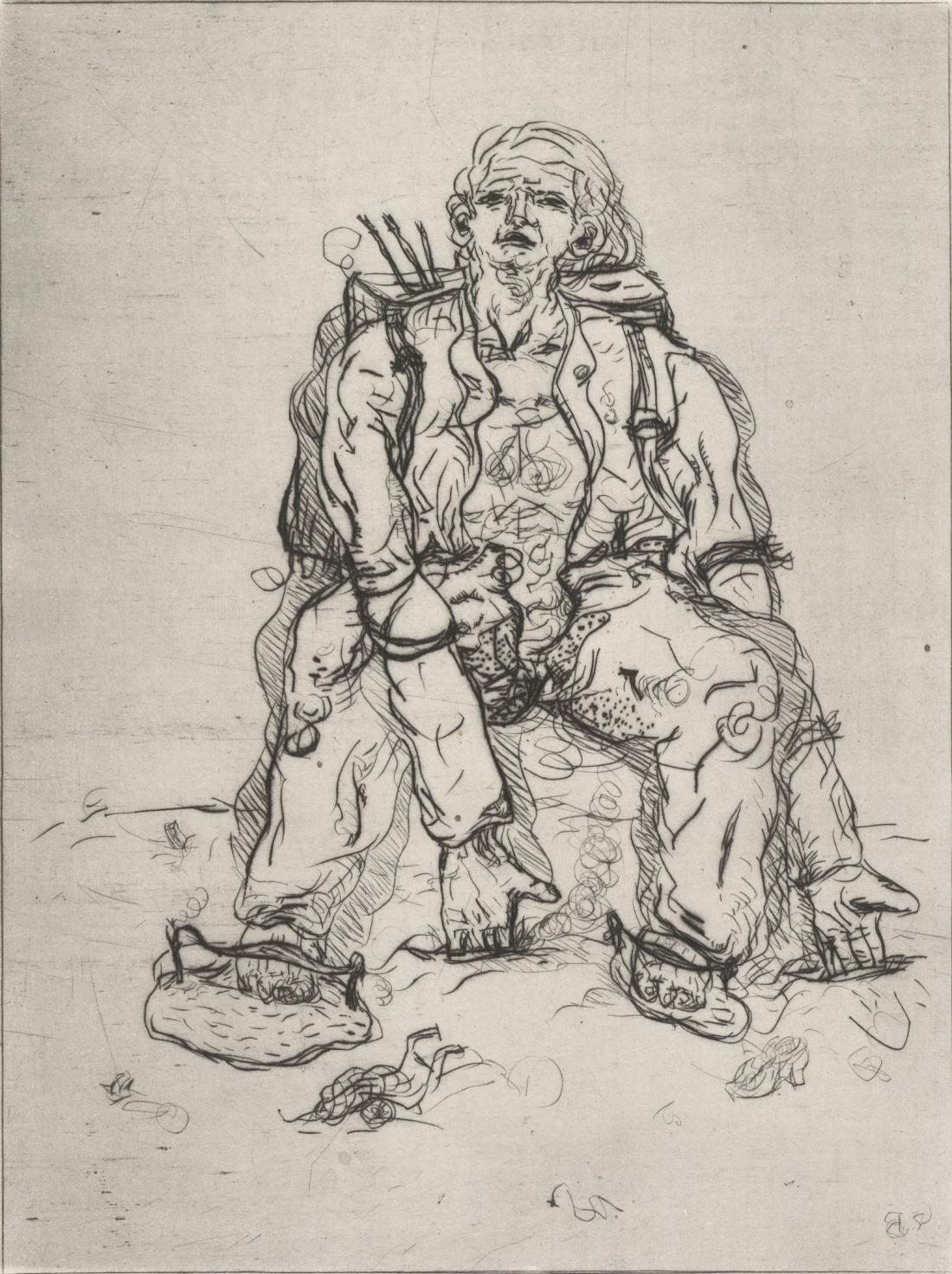

Baselitz’s potent anti-heroes

Produced during the years 1965–66, Baselitz’s Heroes bear titles such as The Shepherd, The Partisan, The Rebel, and many of them are called Neue Typen (which can mean New Types or New Guys). In total, the series comprises some forty paintings and more than a hundred drawings and prints. These depictions of heroes not only see Baselitz grappling with Germany’s traumatic past. The series also ushers in Baselitz’s work with printmaking techniques, specifically etchings, aquatints and woodcuts. The resultant pieces would play a central role in his work on the heroes. The key importance of graphic modes of expression in the Heroes series makes it an even more apt comparison for the Portrayers of Man and their exhibitions of fine-art prints. [fig. 5]

According to John-Paul Stonard, the first work of the Heroes series was a drawing done during Baselitz’s scholarship in Florence in 1965.37 Called Ohne Titel (Untitled), the drawing depicts a lonely humanoid figure walking through a desolate landscape. Viewed in profile, the figure has a dinosaur-like head, a long, snake-like tongue lolling from its mouth. Where the belly would usually be, the figure has a head with a huge eye, and a vast penis pokes out from between its legs.38 Like the Heroes that followed, the drawing shows a contradictory figure. Alone in an undefined landscape, the figure appears monumental and strong, yet also crippled and dejected. Baselitz’s time in Florence stimulated his pre-existing fascination with the strategies and figures of Mannerism, finding expression in the heroes’ disproportionate, elongated and muscular bodies with tiny heads.39

The Hero Paintings also have clear references to Baselitz’s group of paintings collectively known as Die grosse Nacht im Eimer, 1962–63, one of which is housed at Museum Ludwig, Cologne. The Cologne version shows a male figure wearing only shorts, brandishing a grotesquely large, exposed penis. The figure’s black hair, combed into a side parting, recalls Hitler, causing the work to be frequently read as a caricature comment on World War II.

The 1965 painting Der neue Typ, owned by Sammlung Froelich in Stuttgart, is a typical example of Baselitz’s depictions of heroes. [fig. 1] A squat man dressed in shorts and an open jacket with one sleeve missing stands alone in a desolate landscape, a fluttering, red scarf trailing behind him. The figure fills out almost the entire picture, and the huge hands, wide body and small head casts this ‘new type’ as a giant colossus. The fingers of his right hand are caught in some kind of trap, while his left palm is wounded, bearing bloodied stigmata. The stained, tattered clothes, the wounded hands and the trap all tell us that this giant has seen some tough battles, his trials emphasised by his discouraged gaze. However, the impression of fatigue is somewhat contradicted by the figure’s bare, oversized and tuberous erection, suggesting that in spite of all his tribulations the hero still has some form of energy and strength left. He may have been injured but he still has the power to cause harm.

Baselitz’s use of the term ‘heroes’ should undoubtedly be read ironically. Rather than conveying impressions of strength, invulnerability and invincibility, Baselitz’s musclebound heroes appear broken and paralysed. Or, as Max Hollein puts it, they seem to be melancholy survivors in a ruined, chaotic world.40 In those cases where the figure is not equipped with a prominently featured, exposed and erect male member like the one seen in the above example from Museum Ludwig, signalling that the figure does have strength and power after all, the figure is typically naked, but without genitalia. Where the male member would normally be, there is quite simply nothing. In both versions, the potent and the impotent, the artist focuses attention on a specific body part in ways that symbolise either power or powerlessness.

As art historian Uwe Fleckner has stated, Baselitz’s post-heroic heroes are downright ‘confusing’ on several levels.41 Not just because they hark back to a pre-modern figure historically associated with a long-forgotten and traditionally ‘authoritarian’ genre, that of history painting. Nor because the figure is presented with a wealth of inherent and non-heroic contradictions. The Hero Paintings are also confusing because Baselitz chooses to use representation at a time when expressive abstract expression was all-dominant and where figuration was considered anachronistic and met with extreme resistance. As has been pointed out by, among others, the influential curator and former director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich, Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019), abstract expressionism was almost the official style of post-war Germany.42 Against such a backdrop, Baselitz’s choice of representation can be perceived as a ‘disobedient’ rebellion against formal conformity, which indeed it was.43 As Baselitz explains, his opposition to abstract expressionism was closely linked to the dominance that the United States exerted at the time, both politically and artistically:

This dominance of American painting was so persuasive, and so consistent with my convictions, that I had to say: not only did you win the war, you’ve also completely trounced us when it comes to culture. […] I had to do something else. Which is why I came up with a perhaps stupid, an anyway by no means intelligent answer, and did something that made my teacher say: That’s anachronistic, stop doing that, that’s unacceptable!44

In addition to being seen as anachronistic, the historical link between figurative expression and the Nazi regime as well as social realism only made his choice of expression more problematic. But for Baselitz, who grew up in East Germany, this form of representation was by no means alien; quite the contrary. As he himself has stated, he did not feel the schism of representation experienced by most other artists at this time.45 Part of the explanation is that he has always felt like an immigrant in the West. Like someone who, as Ulrich Wilmes puts it, ‘[…] perceives himself as having been involuntarily driven from his biographical and artistic homeland’.46

In his quest for his own voice, Baselitz thus challenges the prevailing opposition towards the use of the human figure in art. In his search for a third way, he finds an expressive, figurative mode of expression that unites the figuratively narrative with the expressiveness of the abstract. By choosing this approach, Baselitz became able to express something that had been missing in Germany for twenty years, placing him among the first German artists to address the trauma of the Second World War in pictures. Or, as Enwezor puts it with the question: ‘In the Heroes and The New Type paintings, were you trying to touch the wound that abstraction was trying to cover up, in a sense, after the war by referring back to a certain kind of German archetypal figure?’47

Baselitz and the new Danish realism

As has been established, portrayals of war-traumatised man emerge much earlier in Danish art than in its German counterpoint. One early example is Dan Sterup-Hansen’s War Blind, a subject on which he worked in 1951–52. [fig. 9] His 1952 etching shows men blinded in the war, now forming the front row of a procession. In the image, the six figures are alone, isolated from the crowd that appears in other variations on the theme. Sterup-Hansen got the inspiration for the scene on Armistice Day in Paris, November 1949, when a group of people blinded in the war took part in a major procession.48 The work thus incorporates a direct reference to reality and to the recent war, and like Baselitz’s heroes it shows wounded participants from the war, presenting war invalids that point directly to the traumatic past. At first glance, the subject seems to address human vulnerability and loneliness in a brutal world, but Sterup-Hansen’s intention was also to tell of humanity’s ability to rise up after defeat. To him, the invalids of war represented ‘a human return to dignity, something universally human that transcended them as individuals’.49 According to the artist, then, the narrative is essentially an optimistic one, speaking of the strength of humanity. While such optimism may be difficult to spot, a similar mode of thinking underpins many of Palle Nielsen’s and Svend Wiig Hansen’s works from the period, works that at first glance also appear to depict human powerlessness against the world’s calamities.

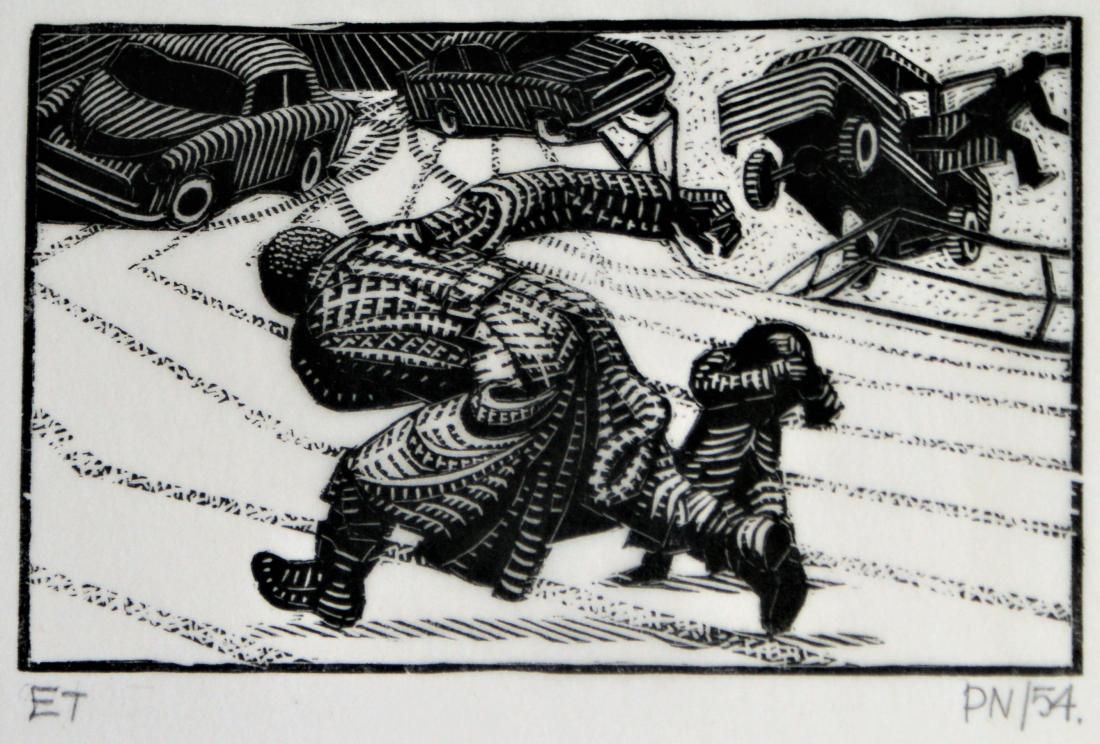

These include Palle Nielsen’s 1954 Soldier and Child series [fig. 6 and 7] and the first part of the series Orpheus and Eurydice from 1955-1959. [fig. 8] In both series, strong, yet also powerless hero-like characters fight impossible battles against much greater forces, and both series express Nielsen’s views on the occupation and post-war years. In The Soldier and the Child, the returned soldier is burdened by his history, but at the same time he struggles to protect the child, the innocent human being, from occupying forces as well as undefined, extraneous threats. In the subsequent series, Orpheus fights an impossible fight to get his beloved Eurydice back while the city around him is ravaged by war, dead people and animals floating in its rivers and lying in the streets. These struggles are simultaneously personal and general.

The Danish Portrayers of Man and Baselitz both create depictions where apparently strong figures have ended up in situations that render them impotent. Those situations are depicted with the human body as the absolute centre of the works. It is these bodies, monstrous, potent, dangerous, yet also wounded, sorrowful, paralysed and disheartened, that tell of the human condition. Of the fall of the individual and the crisis of humanity. In all three artists, the figures inhabit bleak, deserted landscapes. Or, as Wilmes says of Baselitz’s monumental Die Grossen Freunde from 1965: ‘The tattered figures move in gloomy times on top of the ruins of disastrous past, and in deeply darkened space’.50

In addition to the parallels found in their narratives of the human condition in the post-war era, clear parallels can also be found in how they navigate the style wars prevalent at the time. Baselitz and the Danish Portrayers of Man share their desire to find a way around the stereotypical polar opposites that defined art’s potential modes of expression during the period after World War II in both Denmark and Germany. Similarly, reintroducing the human figure into the realm of arts is central to both of them. Baselitz finds his way to what one might call an expressive figurative mode of expression, while the Danish Portrayers of Man become central in defining a new form of realism which, in Denmark, becomes particularly prominent within the realm of printmaking. The Danish movement is defined by a community based on subject matter, on content rather than on a truly common style. They express the vulnerability, both physical and mental, felt by man in an alienating and hostile world. This new realism is broadly similar to what British scholar James Hyman has called Modernist Realism, a style which, in addition to the traits enumerated above, is characterised by the fact that the works focus on the individual’s problems and on the movement of the body in space.51

As was outlined in the above, the present study constitutes the concluding article of a research project whose overall purpose is to investigate the representation and depiction of man in art in Britain, the USA and Germany in order to place the Danish Portrayers of Man and their Mennesket exhibitions in an international context. Taken as a whole, the three studies provide broad insight into how man and the human figure are portrayed within Western art in the immediate post-war years. They also demonstrate clear differences between the four nations in terms of their impulse to investigate and process the trauma of war through art. Whereas the artists of Denmark, Britain and the United States – one nation having been occupied, two openly at war and ultimately victorious – feel an urge to deal with the trauma of the war immediately after its end, the German artists were significantly less inclined to investigate and portray man in the post-war period. Having been the losing aggressor in the greatest man-made tragedy of recent times, one may almost speak of a deliberate state of artistic amnesia in Germany, one where ‘Man’ is the proverbial elephant in the room that is not spoken of. Not until twenty years after the end of the war is man given voice again with the Heroes created by Georg Baselitz, depictions that are deeply marked by internal contradictions.

This research project is supported by the Ministry of Culture Denmark.