Summary

In Wilhelm Marstrand’s portraits, the light-hearted approach found in his early work is replaced by the more formal feel of his later oeuvre. His portraits can be divided into three main groups: friendship portraits, family portraits and official, monumental portraits. His early friendship portraits are informal depictions of fellow artists, imbued by a special sense of intimacy and presence. The family portraits, both those commissioned by prominent bourgeois families and those depicting Marstrand’s own family, tell of everyday, harmonious family life. The commissioned works demonstrate the prosperity that can arise out of adhering to bourgeois virtues such as diligence and industriousness, while the depictions of Marstrand’s own family belong entirely to the private sphere and exude a tender, loving closeness. Finally, the official, monumental commissions depict figures from public life who embody a particular concept or ideal.

Article

Expressions like ‘the eye is a window to the soul’ or ‘a telling look’ say much about the meaning and significance we attach to the eyes and how we perceive human expressions through glances and looks. A direct gaze might indicate a strong presence, but it can also be distant. When speaking of a warm gaze, a cold look, a sad look or a loving look, we might initially think that the eyes are alone in radiating such sentiments, but in fact a complex interplay between the eyes and the facial expressions, the delicate muscles of the face, add up to reveal something about our innermost feelings. We laugh and cry, sometimes out of joy, other times out of sadness; these things happen automatically, thereby revealing our state of mind.

Today, we believe that a good portrait is one in which we can decode the sitter’s psyche, demeanour and entire mental make-up, allowing us to form an impression of the person, feeling their presence and the emotions harboured deep inside them. This is exactly what a talented portrait painter can do. However, doing so does requires the artist to be able to capture and depict all the little nuances that join up to make a face come alive, giving it genuine presence. It is a difficult process, and not everyone masters it. Even among the truly superb artists occasional examples of less successful efforts completely devoid of charisma and life appear. Moreover, a portrait involves several stakeholders, first and foremost the sitter, who may also be the client, secondly the painter commissioned to carry out the portrait, and finally the viewer who will look at the image. The sitter may have a particular idea of how he or she would like to be perceived, and may also have their own wishes regarding a specific way of staging the portrait. Regardless of the sitter’s self-perception, the artist’s perception of their personality is, however, ultimately the crucial aspect of the work.

Nineteenth-century portraiture is characterised by a completely different set of values compared to those of our present-day society. Emphasis was placed on ideals such as diligence, frugality and love of one’s country; bourgeois virtues which could be expressed in the more intimate depictions of the family. However, many portraits of a representative nature were also produced, and such pieces can be more difficult to read because they were intended to show an idea or an ideal rather than an individual trait associated with the person being portrayed. Marstrand’s portraits can be roughly divided into three groups: so-called Freundschaftsbilder, meaning friendship portraits; family portraits; and official, monumental portraits. In the following, a small selection of his portraits will be addressed with a view to assessing the development that took place from his young years up into his late work. Since Karl Madsen wrote his thorough and extensive biography of Marstrand in 1905, the first major book published on Marstrand – apart from minor articles – was Gitte Valentiner’s monograph from 1992. The same year the exhibition Nivaagaard viser Marstrand opened, curated by Gitte Valentiner. It is the most recent solo show to feature Marstrand up until now, representing a time span of almost thirty years. Likewise, Marstrand’s portraits have not received independent treatment since Claus M. Smidt’s article in the catalogue associated with said exhibition.

Marstrand is not best known for his portraits, nor do they account for the lion’s share of his overall production. Nevertheless, he was a dazzling portrayer of the human psyche. He was a master at depicting figures in motion – a trait of which his depictions of folk life offers plenty of evidence – and this is also reflected in some of his portraits, making the painted figure come across in a manner that feels unforced, vivid and natural. Throughout his life, painting people was Marstrand’s main preoccupation; this was where his real interest lay, and figureless landscapes take up little space in his total oeuvre. Whether working with history painting or folk scenes, there had to be some story to tell, but by their very nature individual portraits were rather short on narrative. However, he could compensate for this by placing more emphasis on conveying a story about the sitter’s inner life, as it were.

Marstrand painted group portraits and double portraits as well as portraits of individuals. ‘I have hitherto had to paint for my daily bread without taking into account what would best aid my studies,’ he wrote in a letter to his brother, Troels, in 1836, just before embarking on his first voyage to Italy. And painting for his livelihood meant painting a lot of portraits.1

The first patron

We all know the importance of having a large network and good connections. That holds true today, but was no less true in Golden Age Denmark. Fate and providence are not alone in governing the events of any given person’s life, and indeed it was no coincidence that Wilhelm Marstrand took the first steps toward an artistic career at the age of fourteen. Rather, he was actively urged to do so by one of his father’s good friends, C.W. Eckersberg (1783-1853), a professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts who enrollede the boy.

Similarly, the patron who commissioned no less than three paintings from Marstrand in the 1830s was another friend of his father’s: Christian Waagepetersen (1787–1840), a wealthy wine merchant, purveyor to the royal Danish court and art collector. The first of his three commissions was A Musical Soiree in the House of the Merchant Waagepetersen, 1834, the second was The Waagepetersen Family, 1836, while the third was Romans Gathered for Merriment at an Osteria, 1839, which very aptly for a wine merchant depicts happy Romans celebrating the grape harvest. Unfortunately, Waagepetersen died the following year at the age of fifty-three, marking the end of a patronage that had otherwise had such promising prospects for the young Marstrand.

In his slender book about the wine merchant Waagepetersen, Claus M. Smidt writes that he ‘would become a catalyst for the careers of two of Eckersberg’s most gifted students, the painters Wilhelm Bendz and Wilhelm Marstrand. Their rich talents seem to come to fruition in the tasks that Waagepetersen had them perform’.2 Bendz’s depiction of The Waagepetersen Family, 1830 [fig. 1] shows Christian Waagepetersen seated by his desk in his study, his labours interrupted by the arrival of his wife, Albertine, holding their daughter Louise on her arm while a slightly older child leans up against the father’s leg in a gesture of trust. The portrayal has a natural feel to it, and even though he is probably in the midst of conducting business, family life means everything. Family and work were the hallmarks of a well-run life; they were the be-all and end-all of the bourgeois set of values that held sway in Golden Age Denmark. Even the dog under the desk has been included, symbolising faithfulness and stability. Bendz finished the painting in 1830, by which time Waagepetersen already owned several paintings by him, and were it not for Bendz’s early death he would certainly have received more commissions; Waagepetersen’s eldest daughter Christiane Sophie married Bendz’s older brother, Jacob Christian Bendz, who was a doctor, so there were also familial ties between them.3 Wilhelm Bendz died of typhoid fever in Vincenza in 1832 at the age of twenty-eight. His death would prove a boon for Marstrand, for now he became the one to receive commissions from the wine merchant.4

A Musical Soiree in the House of the Merchant Waagepetersen [fig. 2] or simply Music Night,5 as it was known within the Waagepetersen family itself, is an excellent example of how Marstrand mastered the art of painting compositions featuring many figures right from an early stage of his career. The painting depicts some thirty people who can be identified and recognised from real life, meaning that he essentially did portraits of each of the individual participants. While these portraits were, of course, on a small scale, they still required him to draw sketches of each of the persons featured as part of his preparations. Eckersberg, who was himself a musician and played the viola and the violin, states in his diary that Marstrand drew his face for the Waagepetersens’ painting on two occasions.6 At this point Marstrand was only twenty-three years old, so receiving such a major commission was quite a feather in the young artist’s cap. Even though his training had officially come to a close when he was awarded the academy’s major silver medal in March of 1833, he continued to attend its school of painting for a few years afterwards, meaning that he was still listed as a pupil in the exhibition catalogues.7

As a man of culture and refinement, Christian Waagepetersen was keenly interested in art, music and science alike. The names of three of the sons of the Waagepetersen family testify to the family’s avid passion for music; they were named after the household’s favourite composers, Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven. Waagepetersen held weekly concerts in his stately home in Store Strandstræde 18,8 and Marstrand’s canvas immortalises one of these chamber music concerts.9

The wine merchant played the cello himself, and the painting’s composition centres around him, seated on a small podium in the middle of the scene with his cello. Beside him is his twenty-year-old son Mozart Waagepetersen, who plays the violin. They are joined by two other musicians to form a quartet, with four music stands on the floor before them. Christian Waagepetersen makes eye contact with the composer C.E.F. Weyse, who sits slightly behind him at the grand piano in the right side of the picture. The concert is just about to begin. The walls of the beautiful high-ceilinged room is densely hung with paintings, including Peter Copmann’s copy after Christian Horneman’s pastel of the composer Friedrich Kuhlau, who had died two years previously, and Marstrand’s own Street Scene. Dog Days from 1833.10 Professor Eckersberg appears to the left, while Marstrand himself is leaning up against the double doors; he is right in the centre between Mozart and Christian Waagepetersen. Through the large, open double doors we see Mrs Albertine Waagepetersen and some of the couple’s children seated on a sofa, ready to listen as a servant serves tea.11 The colour scheme is muted; this is an evening event, and the light reflects the glow of the so-called astral lamps, a particular kind of oil lamp that did not cast any downward shadows, making them particularly suitable for evening entertainment.

In 1836, Christian Waagepetersen travelled to Italy without his family, but in the company of a good friend, and prior to his departure he commissioned yet another group portrait, this time featuring his wife and children. The result was The Waagepetersen Family [fig. 3] which shows Albertine Waagepetersen in the drawing room with six of her thirteen children.12 A seventh child is included in the form of a portrait on the wall behind the sofa, a picture painted by the Danish portraitist Louis Aumont (1805–79), who had also done portraits of her parents. She is the family’s fourth child, Suzette, who died in 1829 at the age of fourteen.13 Her portrait hangs between two scaled-down copies of portraits of Mrs Waagepetersen’s parents, the East India merchant Schmidt and his wife, whose iconic full-length portraits Eckersberg had painted in 1818.14

In addition to Albertine and the children, a wet nurse or nanny has just entered the room, cradling a small fair-haired child. This is the youngest son August, who incidentally was also called Beethoven. The wet nurse’s figure brims with health and vigour, suggesting a young woman clearly capable of robust work, and her colourful traditional regional costume with its green skirt, pink, freshly ironed apron, dark patterned bodice over a red blouse and bonnet with an embroidered back tells us that she is from the Hedebo region between Copenhagen, Roskilde and Køge.15 The fertile soil found there made the peasants from this region quite affluent, a good match for the Waagepetersen family: their wet nurse was of rural stock, but presumably from a solid, respectable background.16 She symbolises true, authentic Danish virtues such as diligence, industriousness and health. Virtues associated with the widespread ideas concerning the national character of the Danes.

A marked contrast to the robust wet nurse and her rural costume, Albertine perches on the sofa wearing a delicate, white dress and a white bonnet tied in place with a pink ribbon. Everything is carefully matched; even her craft project, a knitted sock, is pink. The children all play with their various toys, with additional playthings strewn on floor, and one boy is shown sitting on his knees on the chair, turning towards us with a triumphant expression as he presents a drawing of a boy sticking out his tongue. These are a boisterous lot, healthy and spirited children who, entirely in keeping with the ideas of the German educator J.B. Basedow, are allowed to be children, at least within the confines of the home.17 The scene shows a particular moment in time, an intimate glimpse into harmonious, unfettered family life. However, it is also a carefully staged snapshot; everything has been very deliberately selected to tally with the self-image of the bourgeoisie, testifying to how the realism of Golden Age art – especially in portraits – was very knowingly arranged. The scene is entirely in keeping with the family ideals of bourgeois society with the mother as the centre of the family; her hands are never idle, but preoccupied with crafts while the absent father and breadwinner takes care of the financial side of the matter, the family business.18

If we compare this painting with Eckersberg’s The Nathanson Family from 1818 [fig. 4], we see that the genre has undergone certain developments. The depiction of the Nathansons is more of an ‘official’, representational group portrait: with its dancing children and the parents entering the room, the scene has a staged feel to it, whereas the depiction of family life in the Waagepetersen household has a more relaxed, natural air.

Friendship portraits

Before the young artists set out into the world on their Grand Tours, they would often have their picture painted by one of their peers so that their families would have a good likeness to remember them by while they were away. And many of the artists were away for years on end. Marstrand’s first journey lasted five years, and before he left Copenhagen, he had his friend Christen Købke (1810-1848) paint a portrait of him so that his mother would not completely forget what he looked like. The result was one of the most exquisite and charming Freundschaftbilder in all of Danish Golden Age art [fig. 5]. One can clearly imagine the fun they had during its creation, not least because instead of a pipe, Marstrand holds a small, pink rose in his mouth: Marstrand’s mother did not like the pipe, so they decided to replace it with a rose.19 Købke and Marstrand were of an age: both were born in 1810, so by the time this picture was painted they would have been twenty-five years old. Among the group of young artists at the Academy, Marstrand was known for being very cheerful and full of life, and his sense of humour was familiar to all. In 1880, councillor Raffenberg described him in these terms:

Vilhelm Marstrand was a man through and through, strong and independent. He held within him a peculiar blend of seriousness and gaiety, of melancholia and cheerful enthusiasm. His demeanour was rich in contrasts, a carnival of ideas and representations – as is evident from his drawn sketches – his outlook on life and gift for perceiving the ridiculous prompted him towards caricature, in many cases executed to exquisite effect; there was humour, paradoxes, but always merriment.20

Købke’s portrait shows Marstrand looking directly out at us. The white shirt stands out brightly up against the background of the black waistcoat, the black neckerchief and the brownish lapels of the jacket against the equally dark, neutral background. Marstrand looks as if having a rose in his mouth is the most natural thing in the world; he tries to look serious, but the mischievous glint in his eyes clearly suggests that he might break out in laughter at any time.

In 1834, Gottlieb Bindesbøll (1800-1856) travelled to Italy. Prior to his departure, Marstrand painted his portrait so that his family had something to remember him by. Undated, the portrait must have been made in 1833 or 1834 [fig. 6]. Bindesbøll was ten years older than Marstrand, but in many ways they were very much alike when young; they both had a penchant for cheerful living, and for Bindesbøll it was a great relief when Marstrand arrived in Rome ‘so that one could begin living with a bit of merriment again’.21

Marstrand’s portrait shows Bindesbøll seated backwards on a chair, straddling it with his arms resting on the backrest, one hand holding his sleeve, the other gripping the back of the chair. He has a roguish glint in his eye and a small smile playing on his lips; his dark hair is slightly tousled. Bindesbøll radiates energy and confidence, and at the same time the entire situation has an unpretentious, down-to-earth feel. The colour scheme is dark; Bindesbøll is wearing a black jacket and grey-blue trousers and sits up against a backdrop of green wallpaper and grey wood panelling. The final result is a thoroughly informal portrayal of a dear friend.

Before Marstrand himself sets off on his first journey, he painted a portrait of his teacher, C.W. Eckersberg [fig. 7]. By this point Eckersberg was fifty-three years old and had a string of pupils. In 1890, Eckersberg’s biographer, Emil Hannover, described his relationship to some of these pupils in the following terms:

Out of the first litter of his pupils he socialised with the oldest ones, such as Rørbye and Küchler, quite as if they were his peers. He loved the considerably younger Adam Müller as if he were his own Child. Christen Købke was also very dear to his heart, while Marstrand was the one whom he admired the most as an artist. While he received little glory from his female students, he nevertheless appreciated having them. The most diligent was the flower painter Christine Løvmand, the most famous was Lucie Ingemann, née Mandix, wife of the poet.22

There can be no mistaking in how women painters were not accorded much artistic merit, certainly not in Hannover’s eyes, and perhaps not in Eckersberg’s either. But they were a source of extra income, which was always welcome in the Eckersberg household with its many mouths to feed. The depiction of Eckersberg follows the same schema as several other portraits from this period: a brownish background, traditional attire with a white shirt, neckerchief, waistcoat and coat. The waistcoat is green with a delicate golden pattern, and the grey, short hair is left to fall naturally. Eckersberg turns his head slightly to the right, and his attentive gaze is fixed on a point outside the picture frame. He is a handsome man, in the middle of his life, and one senses the warmth with which Marstrand regards him.

On 16 June 1836, Eckersberg stated in his diary that: ‘The morning was mostly spent sitting to Marstrand, but today he finished my Portrait…’23 He would have painted it over the course of a very brief period, only seventeen days, for on 30 May Eckersberg wrote: ‘This morning I sat to Marstrand, who will paint my portrait for Heilmann’. On 16 June the portrait was finished. The patron, councillor Christian Heilmann (1777–1840), was a customs treasurer in Ringsted. He was married to Marstrand’s aunt, Mille Johanne Smith, who was the widow after Christian Kratzenstein-Stub, a friend of Eckersberg’s.24

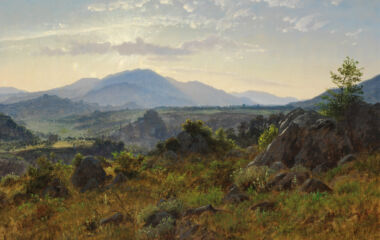

Marstrand’s portrait of Johan Thomas Lundbye wearing a Roman hat dates from Marstrand’s second trip to Rome – and Lundbye’s first and only trip there [fig. 8]. It has a different feel to the portraits previously addressed here; while they have a friendly, outgoing air, this depiction is more monumental and sombre even though it, too, is a friendship portrait. Lundbye has grown a large, dense beard and wears the type of hat favoured by many travellers in Rome. His brown eyes are unfocused, looking at something right beside us as if he were somewhere else in his mind. In his travelogue, Lundbye wrote about having seen the Roman campagna, which all his fellow artists had praised: ‘I must admit: The campagna is the loveliest thing I have ever seen; so great, so noble, I never saw such natural scenery; but in due course the moors of Jutland shall offer me subject matter that may be less rich, yet dearer to me’.25 It was no secret that Lundbye suffered terribly from homesickness throughout his year in Italy, but at the same time he was aware of the impact that his time there would have on his artistic development.

Family portraits

When Marstrand married in 1850 he was thirty-nine years of age, and by that time he had wanted to find a partner and companion for ten years. He repeatedly expressed this in letters to his mother and to his friends.26 He had yearned for someone to share his sorrows and joys and to have a family of his own, so it was a great happiness to him when his dream finally came true.

In The Artist’s Wife and Children in the Studio at Charlottenborg from 1861–62 [fig. 9] the scene is set in Marstrand’s studio in their home at Charlottenborg. His pregnant wife, Grethe, enters the studio holding the hand of their youngest daughter, Ottilie. With this composition, Marstrand highlighted Grethe’s position as the absolute centre of the home; she occupies the central position and is even placed on high, as if perched on a pedestal. The older children are already inside the room; one of their sons, Vilhelm, sits on a step, leaning against a railing with a nonchalant air, one hand buried in his pocket as he looks up at the figures entering the scene, while the eldest daughter Julie runs happily to meet them, her arms open wide and her back turned towards us. The eldest son, Poul, is shown sitting on a chair, looking somewhat resigned; perhaps he is sitting to his father once again. He certainly looks bored. On his lap is a large open book, with six illustrations visible on the page hit by the light. The book in question is an illustrated volume by the German educator J.B. Basedow, featuring a hundred engravings by the artist Daniel Chodowiecki (1726–1801), which ought to greatly appeal to an inquisitive child with its pictures and educational approach to play, nature, animals and so on.27 According to Karl Madsen, Marstrand used Basedow’s Elementarwerke as inspiration when painting clothes and interiors from the eighteenth century, for example in his Holberg scenes.28

J.B. Basedow (1724–90) dedicated his life to being an educator, and his overarching pedagogical idea was that the child should acquire knowledge through play. He drew inspiration from the Swiss Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78), whose 1762 book Émile, or On Education had prompted a sudden interest in pedagogy in Europe.29 Despite his controversial ideas on child rearing, Rousseau had a major impact on modern pedagogy, not least because he saw childhood as a period with intrinsic value in its own right. Basedow spent eight years as a professor at the Sorø Academy, where he taught moral philosophy and the German language; he had been recommended for the position by a compatriot, the poet F.G. Klopstock, who praised him to A.G. Moltke. Basedow’s ideas would prove greatly influential on the Danish school system and child rearing as such, and – who knows? – perhaps Marstrand was also inspired by his pedagogical ideas, in addition to using his Elementarwerke when seeking inspiration for costumes and interiors.

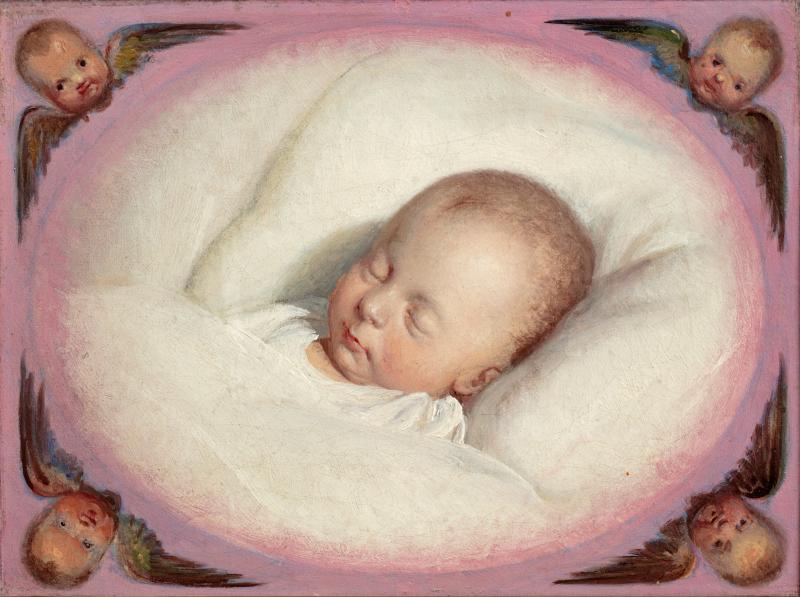

It has often been reported that Marstrand loved children and was fond of having his own offspring in his studio while he worked. There can certainly be no doubt that it was a great joy for him and Grethe to have six children. However, they did experience the great sorrow of having their second child, a daughter, die shortly after her birth. Called Margrethe Kristine, Marstrand painted the infant when she was just four days old. The child reclines peacefully, her cheeks pink, and looks as if she is sleeping [fig. 10].

The other children were painted on several occasions, and while young and still living at home, they were Marstrand’s favourite models. It is likely that he painted his portrait of their youngest child, Christy, shortly after his wife died of typhoid fever at the age of forty-two.30 [fig. 11] Her death left Marstrand suddenly alone with five children, the eldest of whom was sixteen while the youngest was just five years old. There is something very authentic about this portrait; it does not have the staged quality often found in other portraits. Little Christy hugs her doll in her arms, she looks a little distant and lost, but then again her mother’s death meant that she had already tasted the darker aspects of life despite her tender years. Her hair is not freshly combed, and she is wearing an everyday dress in a shade of lavender. She looks like what she is: a real child playing with her doll.

In a later portrait also featuring her two sisters Ottilie and Julie [fig. 12], Christy is four years older. They all look out at their father with serious expressions as he paints them. Ottilie leans in towards Julie in the middle, as if searching for reassurance, thereby causing Julie’s face to cast a shadow over Ottilie’s forehead and eyes, creating a lovely contrast between light and shadow. The colours are muted; the youngest two are wearing simple, lilac apron dresses, while Julie wears a more grown-up cut: a green dress with a red ribbon at the neckline, allowing a glimpse of a white blouse below. Of the three, Christy has the most open and direct gaze.

After Eckersberg’s death, Marstrand took over the former professor’s official residence at Charlottenborg, and in 1854 the family moved in. Marstrand had himself become a professor in 1848 after the death of Martinus Rørbye (1803-1848), but he was not given a flat at Charlottenborg until he was also made director of the Academy. An exchange of letters offers excellent insight into how the Marstrand couple strongly disagree on how the new home should be decorated.31 He wants it to be a dignified residence befitting the status of a professor and director of the Academy; she wants the home to be adapted to a growing family and its needs. Bindesbøll helped them with designs for the renovation, and by and large Grethe Marstrand got her own way. One of the outcomes of this was that Marstrand lowered the floor level in his studio to make the ceilings high enough, thereby making the windows sit high up on the walls, giving off only a studio-type light.32

In the first volume of her memoirs, the Swedish author Helene Nyblom relates stories about the various artists and cultural personalities she met during her childhood and early youth. Born in Denmark as the daughter of the painter Jørgen Roed, she married a Swedish senior associate professor of aesthetics, Carl R. Nyblom. After her marriage in 1864, she moved to Sweden and stayed there for the rest of her life. Of course, her description of Marstrand and his home are tinted by being a young person’s experiences, but this also helps make the older woman’s memories and her vivid descriptions an interesting mix of first-hand experience and hindsight.

She knew Marstrand very well and was a frequent visitor in the home, which she describes as very generous. The Marstrand family were lavish in their hospitality; while they did not arrange parties as such, their door was always open to friends and acquaintances:

They knew many people, and many came. Without being in any way excessive in terms of food and drink, they kept a fine table, and you had the feeling of being in a very wealthy home. This was also best suited to Marstrand’s temperament, which was lavish by nature. I cannot even envision him being poor or facing the pressure of money worries. His entire being had something of the fullness and power of the Renaissance artists, something sovereign and rich, which both impressed and delighted one.33

Such a description would undoubtedly have delighted Marstrand, who would sometimes be overwhelmed by doubts about his own capabilities as an artist, questioning whether he was able to meet the ideals he himself had set up as artistic goals.34

A different kind of family portrait

A very different kind of family portrait can be observed in Portrait of Otto Marstrand’s two Daughters and their West-Indian Nanny, Justina Antoine, in the Frederiksberg Gardens near Copenhagen [fig. 13]. Commissioned by Wilhelm Marstrand’s eldest brother, Otto Marstrand, the portrait was made while the family was visiting Denmark in 1857. A merchant by trade, Otto Marstrand set out for Saint Thomas in the Danish West Indies in 1830. In 1845 he married Anna Dorothea Nissen in the Lutheran Church in the town of Charlotte Amalie on Saint Thomas. They had two daughters, Emily Othilia and Annie Lætitia, who were nine and seven years old when they were painted by their uncle. The family’s return to Denmark was prompted by a violent cholera epidemic in the Danish West Indies in 1856, which spurred them on to visit to their relatives in Denmark in order to avoid contagion. Cholera was quite a scourge of the time; the disease had also killed C.W. Eckersberg just four years previously, in 1853, albeit this was in Copenhagen. And in the 1830s, artists also regularly struggled to avoid cholera in Rome.

Marstrand’s portrait is unusual, but not unique. Back in 1838, N.P. Holbech (1804-1889) had already painted his eldest daughter Marie on the arm of her nanny, Neky [fig. 14]. The latter was originally from the West Indies; her costume suggests that she was, more specifically, from Martinique. It was very common for Danish families to bring their nannies home with them when they left the tropical colonies.35 Black nannies were highly sought after because they were considered loyal and trustworthy. Neky was in service in the household of Admiral Hans Birch Dahlerup, and Holbech probably ‘borrowed’ her in order to deliberately play on the coloristic differences between the black woman and the small, white child. Moreover, Holbech was himself born on a sea voyage between Tranquebar and Denmark, which may have given him further impetus to incorporate the colonies in his pictures. The result is a very charming, exotic and different portrait compared to the portraits generally seen at the time. The enslaved won their freedom with the abolition of slavery in the Danish West Indies in 1848, so Neky would have been a slave, while the Marstrand family’s Justina would have been a freed slave when she visited Denmark in 1857.

There can be no doubt that Marstrand has thought Justina exotic – ‘picturesque’, as he called it – a fascination borne out by the unusual fact that she, a servant, is the main focus of the painting. The composition is centred around her rather than on the Marstrand family. She is also the prettiest of the lot, making her a natural choice. Looking at the various titles associated with the painting over time, it is quite clear that the nanny is the main protagonist of the portrait. At the Charlottenborg salon in 1859, shortly after it had been painted, it bore the title A Negro Girl with Two Children, Study, and at the large Marstrand Exhibition in 1898 it was still called A Negro Girl with Two Children. This title was also used in Karl Madsen’s biography in 1905.36 Theodor Oppermann simply called it Negro Girl in his small volume on Marstrand from 1920.37

All of this is only to make clear that the nanny was always the chief figure of the portrait. Writing about this painting, Karl Madsen says:

As a rule, Marstrand applied a great deal of thought and effort to his portraits. Yet in 1856, he appears to have painted a piece quite con amore, an amusing picture of two little girls in blue-chequered dresses; these are Marstrand’s West Indian nieces out for a walk with their nanny, a negress wearing a yellow Turban, white dress and vermillion shawl, set in a landscape where the little girls’ parents and brother follow them at some distance;38

The fact that Madsen thinks the painting ‘amusing’ speaks volumes about the general perception of people hailing from other backgrounds and with other skin colours in the early 1900s, and it is quite appalling to note that this was a perfectly commonplace attitude as late as 1905.

The two little girls stand with the nanny between them in the foreground of the painting, while their parents and older brother Nicolai perambulate at a suitable distance in the background. The girls each hold on to one of Justina’s arms the way children do with someone they trust. She, in turn, does not hold the children, but stands with her hands placed on top of each other in front of her; she cradles herself – she is not part of the family. Her attire is very striking with the brightly white dress, its small collar crisp against the dark skin, and the characteristic West Indian chequered headscarf in yellow, red and green. After 1848, these were the Sunday clothes of the West Indian nannies: now that they were no longer enslaved, they were free to choose what to wear.39 To this we must add the red shawl falling in soft folds down around her shoulders. The fact that she is dressed in the colours of the Danish flag is no coincidence. Being part of the Marstrand household, she was to be regarded as Danish, although with an exotic touch. The young nanny’s direct gaze signals concern, but also dignity.

Monumental portraits: Mrs Heiberg and N.L. Høyen

A very different case is provided by Marstrand’s full-length portrait of one of the period’s great and much-admired cultural personalities, the actress Johanne Luise Heiberg [fig. 15]; a portrayal that is far more monumental and entirely devoid of props.

Completed in the beginning of 1859, the painting is now housed at the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle. When it was first presented at the Charlottenborg salon, it was the target of a great many harsh words. According to Mrs Heiberg, ‘a veritable outcry went up against it by the visiting public. It was deemed to be hideous, far too serious, far too lachrymose in feel; indeed, in the eyes of some it veered towards the ridiculous, – and I was compelled to defend it against detractors on a daily basis’.40 Mrs. Heiberg’s own explanation for the outrage is that she did not wear a crinoline, a corset or any of the other fashions prescribed at the time. But Mrs Heiberg would not allow herself to be dictated; she refused to wear garments thus designed to repress women. Instead she wears a dark, figure-hugging dress over a chemise and a white blouse, its collar open; the overall feel is very feminine. In the eyes of the public, however, the most outrageous aspect was the way in which she pulls the cream-colored silk shawl around her, clearly revealing the outline of her body underneath the shawl; the public found this far too bold and sensual.

At the same time, Mrs Heiberg was very aware of Marstrand’s own trials and tribulations during the creation of the portrait: ‘One of the last times I posed for him, he said, while beads of perspiration formed on his forehead: “It is enough to drive one to despair! There is a chiselled aspect to your physiognomy which I dare not surrender, for it gives you your distinctive quality. Yet if I express this on the canvas, then the softness of the lineaments also found there disappears. The task is to unite them both, and I fail to do so’. 41 Marstrand was fully aware of his sitter’s characterful facial features, which combined something chiselled with a feminine softness, and apparently he struggled to bring out both of these traits simultaneously.

Mrs Heiberg stands in front of a green background, looking out at nature through an aperture in a veranda-like architecture; just outside a pink rose winds its way up a slender pillar, almost as if lending emphasis to the vertical lines of Mrs Heiberg’s own slender figure. In the distance we glimpse some grass and water, perhaps the Sound. She looks pensive, and Marstrand himself articulated what he wanted to achieve with his portrayal of Mrs Heiberg in these terms: ‘And then the public is angry that you look serious! Firstly, I have seen you wearing that expression, and secondly, I have wanted this painting to have, if I may be permitted say so, a historical significance, serving to commemorate this time of your life when a shameful injustice had forced you to abandon your public endeavours’.42 The shameful injustice to which Marstrand alludes is Mrs Heiberg’s exit from the realm of theatre – she had resigned from the Royal Danish Theatre in 1857 after some conflict with the new theatre manager.

Karl Madsen believes the portrait to be among the very best ever produced by Marstrand, and he seconds the artist’s explanation: ‘– This noble figure, shrouding her arms in a white shawl in a pose of great plastic beauty, imbued with the dignity of an ancient statue, appears here as the exalted and wronged muse of the art of acting. Her gaze, full of thought, looks dreamily out across the blue Sound that laps the shores of Tycho Brahe’s island. And she said: “Oh, My country! Tell me, what was my offense!’43 Mrs Heiberg had been part of the world of theatre since she was twelve, first as part of the children’s ballet corps at Hofteatret, then as an actress, and now she was being ousted by the new manager. The public regarded this as an unheard-of outrage, for Mrs Heiberg was the Royal Danish Theatre. However, she soon returned to become the theatre’s first woman stage director.

According to Helene Nyblom, Mrs Heiberg was very keen to be involved in how the portrait should be staged: ‘Both Bissen and Marstrand suffered when portraying her, as she wanted to decide for herself what the work of art should be like. “Do not look at that one,” said Marstrand to another painter who was inspecting Mrs Heiberg’s portrait in his studio. “I did not paint it, Mrs Heiberg did that herself”.’44 The model had very definite opinions about the dress, pose and facial expressions to be used; she had a strong sense of self-worth, having been the theatre’s most highly celebrated prima donna since her youth. Now forty-seven years of age, she was a mature woman who was used to getting what she wanted, and this also held true with Marstrand.

However, she had not anticipated how the changing fashions would soon make the dress she was wearing in the painting appear too short. She responded by having a small change made to the painting: ‘After the portrait was fully finished by Marstrand, it underwent a slight change. When fashions changed in Mrs Heiberg’s later years, the dress in Marstrand’s portrait seemed to her annoyingly short. She asked Carl Bloch to extend the dress with a bit of a train, and he fulfilled her wish. –’.45 The fact that Mrs Heiberg chose Carl Bloch for the task of extending the annoyingly short dress was no coincidence. Being a student of Marstrand, he was an obvious candidate for the task.

Regarding the subsequent fate of the portrait, Mrs Heiberg relates how a secret admirer of hers had approached Marstrand shortly after it was finished, offering to buy it with the intention of giving it to the actress. However, she declined the offer on the grounds that ‘It would seem to me downright eerie to have to see myself thus standing in a certain position every day, staring down at me’.46 Marstrand then suggested that the painting be hung at the Royal Picture Gallery at Christiansborg instead, which suited the patron and model alike. When Christiansborg perished in a fire in 1884, the painting was rescued and relocated to its final place at Frederiksborg Castle. The reason for this was that the secret buyer was none other than the master brewer J.C. Jacobsen of Carlsberg fame, who after the fire at Frederiksborg Castle in 1859 undertook the reconstruction of the castle. The entire episode caused a warm friendship to evolve between the brewer and the prima donna.47

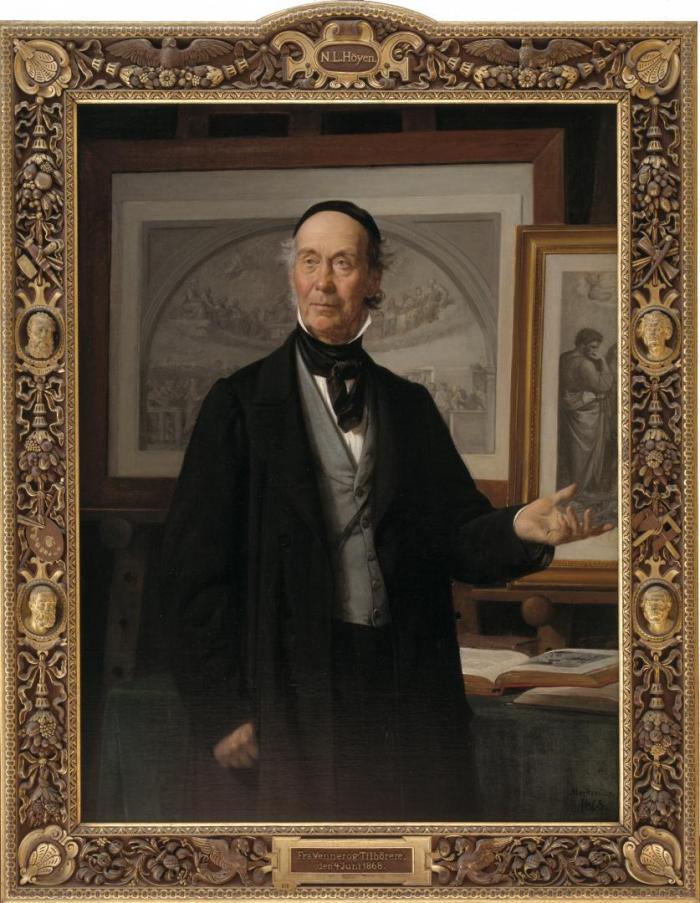

When Marstrand was commissioned to paint a portrait of his teacher and friend, art historian and critic N.L. Høyen (1798-1870), on the occasion of the latter’s seventieth birthday, he quite deliberately chose to portray Høyen in his proper element: as a teacher [fig. 16] This was the position through which Høyen had exercised such enormous influence in his long career, partly on the young artists, and partly as the person who put art history on the agenda in Denmark. The portrait is reminiscent of a modern snapshot: Marstrand has caught him in an everyday situation, giving a lecture on Raphael’s art. Høyen is in the process of interpreting Saint Cecilia from 1515, pointing to the painting with his gesturing left hand.48

Cecilia is surrounded by four saints, but we see only a third of the total work, giving us a glimpse of one of the saints. In those days there was no PowerPoint available to help teachers present Renaissance art, but there were beautifully framed engravings placed on easels; behind him is Raphael’s The School of Athens from 1509, while a few open, illustrated books sit on the table.

The fact that Marstrand portrayed Høyen as a communicator of Italian Renaissance art is food for thought, given that back in the 1830s and ‘40s all of Høyen’s students had their heads filled with the importance of his overriding mantra at the time: creating a national, distinctly Danish art. In his lecture On the Conditions for the Development of a Scandinavian National Art, which Høyen had given in March 1844, he encouraged artists to travel around the country and paint what was distinctly and typically Danish. Marstrand, however, was not among the most responsive pupils on this particular issue, which probably explains his choice of subject matter here. Furthermore, as a young man Marstrand had himself experienced how Høyen could speak about the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel for days on end, and in a letter from Rome he had told Høyen about his own admiration for Raphael during his first trip to Italy: ‘As regards the old works of art here, one can almost be said to grow more afraid for oneself and the present state of art than one is encouraged to follow the old master; for this Raphael is incomprehensible. Art will never take on such significance again. – ’.49 Marstrand was only too fully aware of his own limitations and would remain so throughout his life.

The painting was donated to Høyen by ‘Friends and Listeners’ (‘Fra Venner og Tilhörere’), as it says on the frame, which is a work of art in its own right, richly carved and featuring four small medallions with portraits of the sculptors H.W. Bissen and H.E. Freund, the architect Gottlieb Bindesbøll and the painter J.Th. Lundbye. The medallions were clear references to four deceased, but greatly admired artists, all of whom had been among Høyen’s friends.

Karl Madsen was enthusiastic about the composition, but not about the actual execution. He points out that these shortcomings may be due to the eye disease that Marstrand suffered from when he got older. Madsen refers to Marstrand’s astigmatism, a condition caused by an irregularly shaped cornea which results in blurred and distorted vision.50 Even so, Madsen does conclude that this is unlikely to fully explain the imperfections, especially given that Marstrand’s peers did not fare much better: ‘Neither Constantin Hansen nor Roed were astigmatics nor given to painting mostly without a model, and yet they grew lacklustre in colour, mannered in form in their older days. The sense of freshness and delicacy in the perception of such things can easily be lost when a painter ages.’51 Age is the culprit. Several Danish Golden Age artists did not reach old age, and according to Madsen, things went downhill for those who did.

Still, the portrait is not entirely devoid of quality and spirit. The theologian Johannes Fibiger, who was also part of the circle attending the weekly gatherings hosted by Høyen and his wife, describes how Høyen was a magnificent public speaker. Once he was in full spate, ‘his expressiveness grew in dignity and glory, transforming the lecture into a mighty flight of thought carried aloft by an inner fire’.52 Marstrand’s intention was quite undoubtedly to portray precisely this commitment, the energy and dedication to art that animated Høyen when presenting great art. Høyen looks out towards some distant point, as if that was where he got his inspiration from, even though we cannot escape the fact that he seems rather distant – an impression which probably has something to do with Høyen’s physiognomy itself. If one compares this depiction with other portraits of him, such as Constantin Hansen’s 1855 portrayal, we find that the same holds true here: he looks out at the viewer, but not with a fixed, direct gaze; the overall effect is more vague and absent-minded [fig. 17]. Perhaps Constantin Hansen and Marstrand both set out to show that in spirit, Høyen occupied a completely different, more ideal place when addressing older art.

In other respects, Høyen was a modest man; he was ‘extremely frugal as regards his personal requirements’, and Marstrand has portrayed him wearing the garment he always wore: a so-called ‘mandarin’, a name used to describe a loose coat reminiscent of a dressing gown.53 With this he wore black trousers, a grey waistcoat, a white shirt with stiff, upright collars of the ‘Vatermörder’ type (literally ‘father-killer’), a black neckerchief and a small black cap. When Høyen died, Marstrand wrote the following in a letter to his cousin: ‘Also, we have suffered a great loss with the passing of Høyen – he was an excellent champion and support for us artists – and one can only take joy in the fact of having known him, he has done great things for our art, and we shall miss him always. Fibiger delivered a beautiful eulogy’.54 Not all artists heeded Høyen’s calls to portray their beloved homeland with the same slavish devotion as P.C. Skovgaard (1817-1875) and Lundbye. Marstrand, in fact, did not, but even so he acknowledges the great importance that Høyen had for all of them, as a teacher and as a good friend.

Compared to Constantin Hansen’s portraits of Høyen from 1853 and 1855, both of which have muted colours, an entirely neutral background with visible brushstrokes and a complete focus on the sitter, who is depicted without props or symbols, Marstrand’s portrait of Høyen is more narrative in nature, full of references to the teacher’s endeavours. A choice entirely consistent with the fact that this was a tribute portrait celebrating a landmark birthday, not a friendship portrait of a more private nature.

The art of taming an uncontrollable temperament

Marstrand’s large production testifies to his extreme diligence. At the same time, his flagging belief in his own abilities and slightly frayed self-confidence would sometimes make life difficult for him – a trait oft-repeated in the narrative about Wilhelm Marstrand. Helene Nyblom has provided a very apt description of the artist’s real dilemma:

There was something about Marstrand that reminded me of a captive lion who is far too regal and strong to be caged. His nature was so rich and so multi-faceted that it somehow could not fully find expression for all the things it contained. The large number of sketches and drawings he left behind demonstrates how he was full of teeming thoughts and feelings, and his prolific facility was so ferociously energetic that he found spending a long time working on the same picture a strain’.55

The speed with which Wilhelm Marstrand produced his art within all sorts of genres was compounded by an ever-present sense of restlessness in him, a trait which may have stood in the way of him fully immersing himself and focusing on what he did best. His exuberant talent had a personal boldness and urge for freedom which struggled to unfold itself within the narrow confines of the Academy. The portraits were a different matter because they represented something more concrete. Here he did not have to tame his uncontrollable temperament, because by its very nature the portrait genre contains a range of more or less accepted norms, although artists were of course free to experiment within these parameters. Also, he did not have to devise complicated compositions, except possibly in his large group portraits, but these did not constitute the majority.

As described in the above, Marstrand’s portrait art can be divided into three main groups: friendship portraits, family portraits and monumental portraits. The early Freundschaftbilder are all small, informal depictions of fellow artist, infused by a sense of intimacy, sensuousness and great presence.

The family portraits, which includes commissioned paintings of prominent bourgeois families and those depicting Marstrand’s own family, all speak of mundane, everyday life, of a happy and harmonious family life. The commissioned pieces demonstrate the prosperity that arises out of bourgeois virtues such as diligence and industriousness. This is also evident from the sheer size of the paintings; several of these works were painted as full-length portraits, a format which Marstrand fully mastered. Something rather different is at stake in the depictions of Marstrand’s close family, which belongs entirely to the private sphere. This is not about parading one’s wealth to the outside world, but rather about empathy and closeness.

Finally, there are the more monumental commissions depicting official figures in full or half-length portraits while also representing an ideal or an idea. The unpretentious, laid-back outlook of the early works is gradually replaced by the more formal expression of his late work, a natural progression because of the great differences between the contexts involved – for example whether the paintings would be presented in private or public settings.

Right from the very beginning, dating back to his earliest drawings, Marstrand’s overriding intention was to portray people and their comings and goings; this was where his true interest lay. In this regard, crowd scenes and history paintings took precedence, both in the artist’s self-perception and among the critics. Even so, he stuck to the portrait genre throughout his life, partly because he was preoccupied with the portrayal of humanity, and not least because, as he himself put it in his young years, he had to paint for his daily bread.

Bibliography

C.W. Eckersberg’s diaries, vol.1-2, published and edited by Villads Villadsen, Copenhagen 2009

Dansk Guldalder. Verdenskunst mellem to katastrofer, ed. Cecilie Høgsbro Østergaard, National Gallery of Denmark 2019.

Johannes Fibiger: Mit Liv og Levned som jeg selv har forstaaet det. Published by Karl Gjellerup, Copenhagen, Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag 1898.

Fra den bedste side. Portræt og følsomhed i guldalderen, eds. Gertrud Oelsner og Anna Schram Vejlby, Copenhagen, Den Hirschsprungske Samling 2017

Emil Hannover: C.W. Eckersberg. En Studie i dansk Kunsthistorie, Kunstforeningen, Copenhagen 1898.

Johanne Luise Heiberg: Et liv genoplevet i erindringen, vols.1-4, Copenhagen, Gyldendal 1974.

Ulla Lunn: Stedet fortæller. Om Dansk Vestindien, Copenhagen, Gad, 2016.

Karl Madsen: Wilhelm Marstrand 1810-1873. Kunstforeningen, Copenhagen1905.

Karl Madsen: ”Tilvæksten i Museets Repræsentation for Marstrand”, in: Kunstmuseets Aarsskrift 1917, København Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, H.H. Thieles Bogtrykkeri 1917.

Karl Madsen: ”Tre billeder af Marstrand”, in: Kunstmuseets Aarsskrift 1919, København Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, H.H. Thieles Bogtrykkeri 1919.

Otto Marstrand: Maleren Wilhelm Marstrand, Thaning & Appel 2003.

Kasper Monrad: Dansk Guldalder. Lyset, landskabet og hverdagslivet, Copenhagen: Gyldendal 2013.

Helena Nyblom: Livsminder fra Danmark 1843-1864, Forlagt af H. Aschehoug & Co., Copenhagen1923.

Hans Edvard Nørregård-Nielsen: Dansk guldalderkunst. Fra Abildgaard til Hammershøi, Dansk kunst fra 1800-tallet i Aarhus Kunstmuseums samlinger, Aarhus Kunstmuseum 2000.

Theodor Oppermann: Wilhelm Marstrand. Hans Kunst og Liv i Billeder og Tekst, G.E.C. Gads Forlag, Copenhagen 1920.

Etatsraad Raffenberg: Vilhelm Marstrand. Breve og Uddrag af Breve fra denne Kunstner. Samlede og ledsagede med nogle indledende Ord, J.H. Schultz, Copenhagen, 1880.

Peter P. Rohde: Søren Kierkegaards dagbøger 1. juni 1835, 1961 vol. I 1834-43.

Gitte Valentiner: Nivaagaard viser Marstrand, Nivå, Nivaagaards Malerisamling, 1992.

Gitte Valentiner: Wilhelm Marstrand. Scenebilleder. En monografi af Gitte Valentiner, Copenhagen, Gyldendal, 1992.

Viljen til det menneskelige. Tekster omkring Julius Lange. eds. Hanne Kolind Poulsen, Hans Dam Christensen, Peter Nørgaard Larsen. Museum Tusculanums Forlag, University of Copenhagen 1999

Øregaard. Tiden Kunsten & Den Vestindiske Forbindelse, ed. Sidsel Maria Søndergaard, Øregaard, 2010