Summary

The article addresses a series of four male portraits by the Italian Baroque painter Girolamo Troppa. The series is placed within an historic, iconographic and philosophical context, and arguments are presented to support the contention that the portraits depict Homer and Vergil as representatives of the art of poetry and John the Baptist and Saint Peter Penitent as representatives of the Old Testament and the New Testament, combined here to represent the two branches of human knowledge or ‘faculties of the spirit’ known as Poetry and Theology. The series is regarded as a visualisation of the Platonic concepts of ‘divine inspiration’ and prophetic and poetic furor. The article also analyses Troppa’s colourism on the basis of the concept of unione, and his compositional devices are considered on the basis of potential visual sources of inspiration found in the work of Cesare Ripa, Giuseppe Ribera and others.

Articles

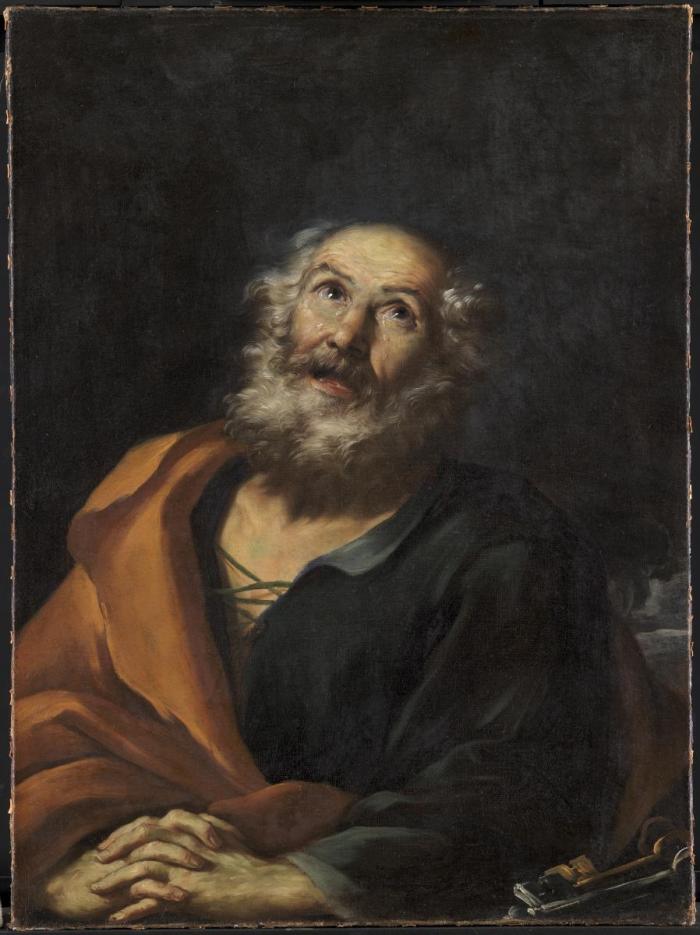

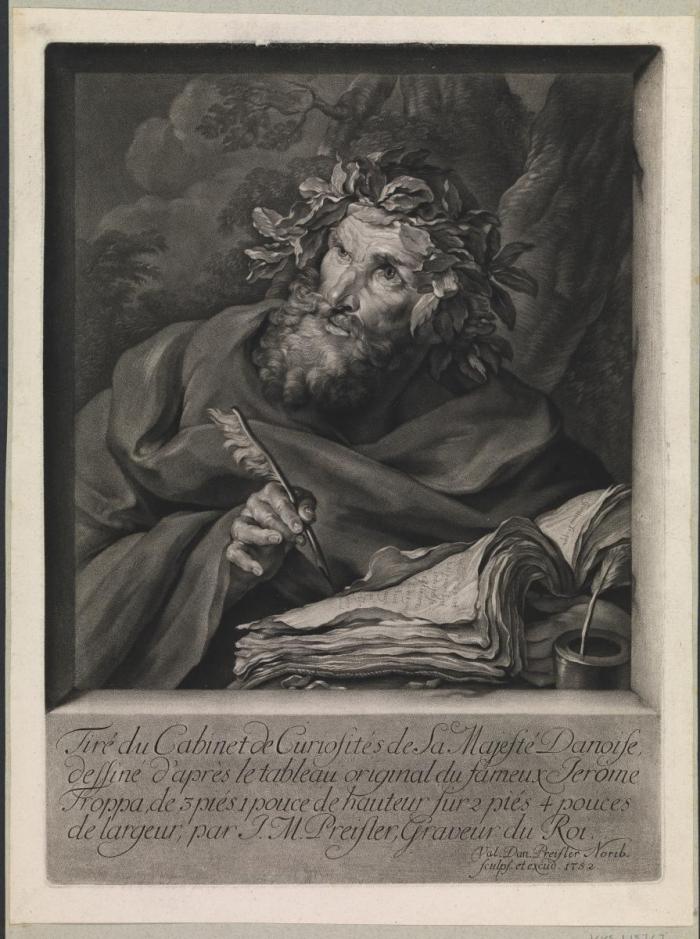

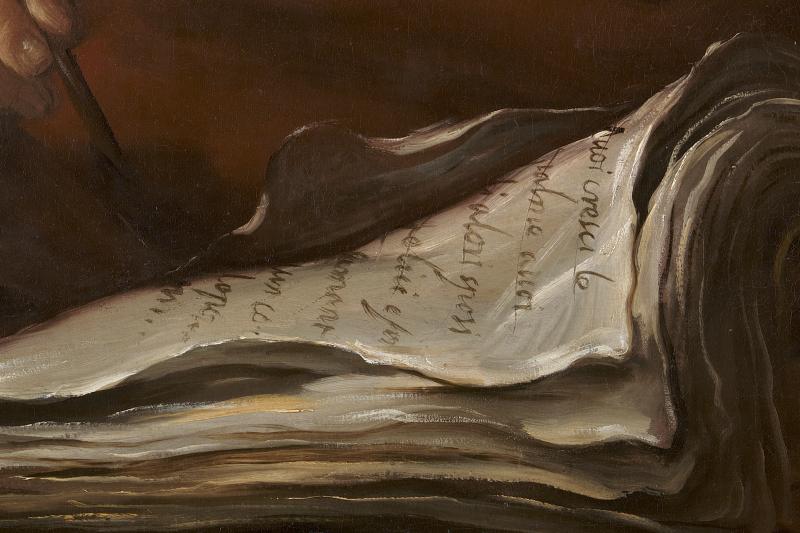

Eyes ablaze with inspiration: an idea takes shape while a pen is held poised above the open book. That is how the Italian painter Girolamo Troppa (1637 – circa 1710) depicted his poet-philosopher. [fig. 1] The fire and untamed ferocity of creativity is clearly conveyed by the fiery eyes and the tousled beard. The poet-philosopher leans across a book whose pages he is about to fill with great thoughts. The text of the book cannot be deciphered, except for a single line – the artist’s signature.

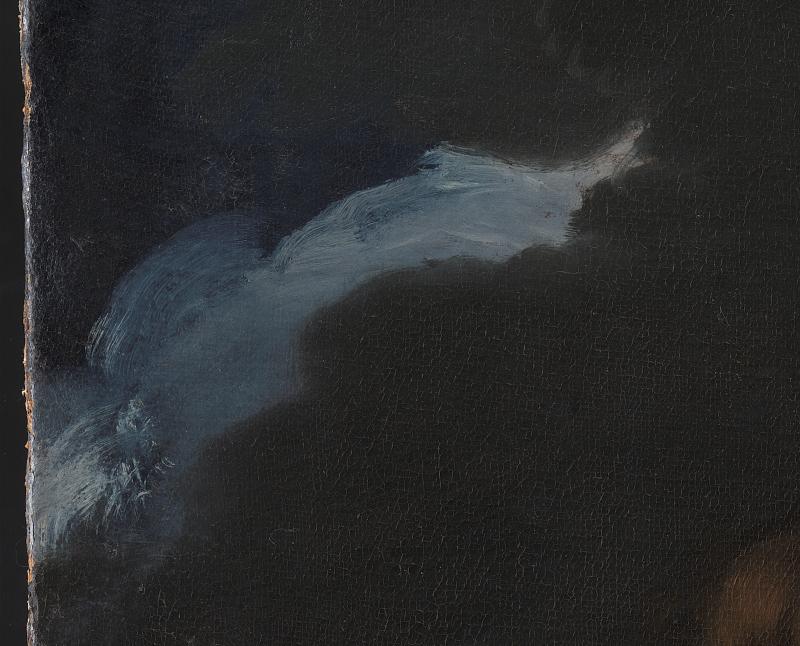

Troppa’s poet-philosopher is one of a series of four paintings featuring half-length portraits of emotionally agitated men, enraptured by the forces of creative imagination or religious pathos. The paintings are nocturnal scenes in which the moonlight stands out as a bright nimbus around the dark clouds in a blue-black sky. The paintings were purchased for the Danish king Frederik III (reign 1648–72) as ‘Four portraits of ancient philosophers’ [4 Stykker af gamle Filosoffer, literally ‘Four pieces showing old philosophers’], but the museum’s most recent printed catalogue identifies the four men as Homer, Virgil, John the Evangelist and Peter, disciple of Jesus.1 [figs. 2-4]

Two questions and a hypothesis

Who are the four men? The objective of this article is to shed light on the various identities attributed to these figures through the ages. It also aims to discuss the raison d’être of this series of paintings: do these two disparate pairs have anything to do with each other? Why bring together two ancient poets and two biblical figures in one series?

The theoretical basis of this study is that of art historical hermeneutics, contextualising the paintings in terms of iconography and philosophy. The theory underpinning the study takes a dual approach: it sees the series as depicting two branches of human knowledge, Theology and Poetry, and it sees the series as visualising the Platonic concepts of prophetic and poetic inspiration. The article argues that Troppa gives visual form to divine inspiration in two versions, one mundane, one Christian. Before unpacking this in greater detail I shall process to outline the provenance of the series and the history of the research done on it.

Acquisition and identifying the figures

The Norwegian-born architect and painter Lambert van Haven (1630–95) was sent on a Grand Tour and collecting expedition to Italy by the highly learned Danish king Frederik III.2 Van Haven not only acquired paintings, but also books, rare objects for the royal Kunstkammer and mathematical instruments intended to aid the construction of buildings and fortifications. His journey began in Copenhagen on 29 September 1668, and his first destination was Venice. Van Haven stayed in Venice from 8 December 1668 to 24 March 1669, and then set out for Rome via Bologna and Florence. He spent more than a year in Rome – residing there from 6 April 1669 to 15 June 1670. While in Rome Van Haven acquired many paintings, including the series under scrutiny here, a Mary Magdalene (SMK, inv. no. KMSsp120) and a Jacob’s Ladder (SMK, inv. no. KMSst310) by Troppa.

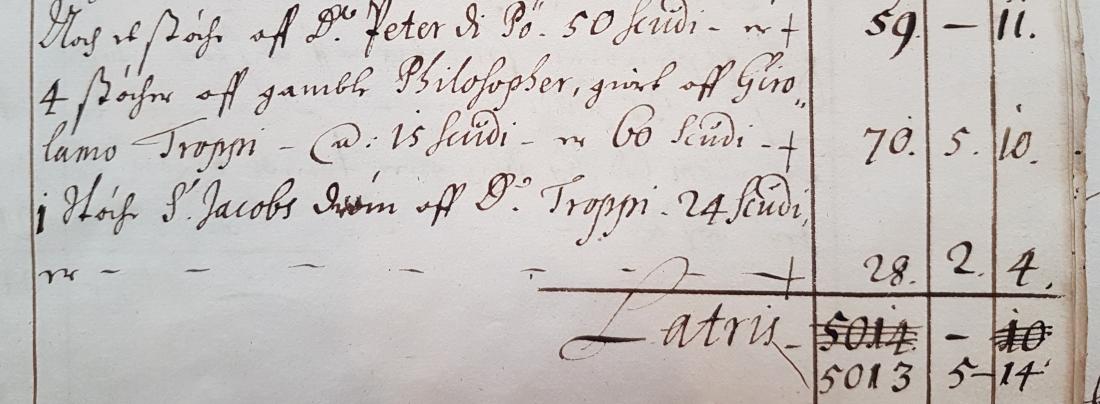

The series is mentioned in a single entry in the accounts of Rentekammeret [the Royal Treasury]: ‘4 støcser aff gamble Philosopher, giort aff Girolamo Troppi – a: 15 scudi – er 60 scudi’ [4 pieces of ancient philosophers, done by Girolamo Troppi – each: 15 scudi – total 60 scudi].3 [fig. 5] It is interesting to note that Van Haven identified the figures as philosophers. Even though this identification will prove to have been erroneous, it conveys interesting information about how philosophers were a much-lauded motif at the time. The ancient thinkers were ‘Christianised’ and regarded as model examples at a time when Neoplatonism and Neo-Stoicism were strong movements within the creative classes of the day. Renouncing material goods and seeking to cultivate the soul and the faculty of reason in meditative contemplation was regarded as the very acme of virtue.4

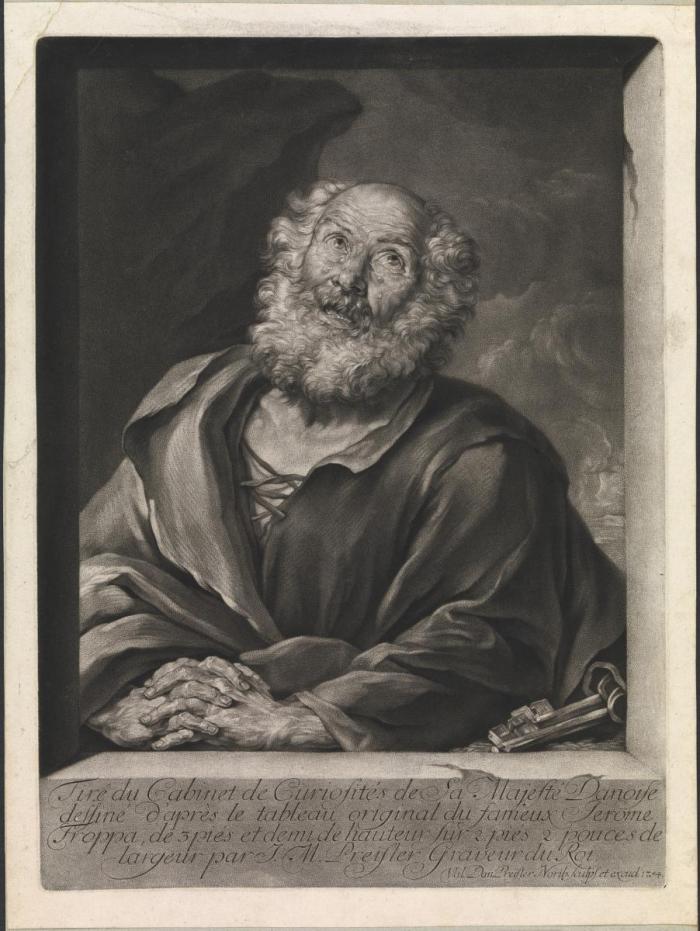

The 1690 Royal Danish Kunstkammer inventory describes the four paintings as follows: ‘Painting of Saint John. / Ditto of Saint Peter. / Paintings of two poets, supposed to be Ovid and Horace. All painted in Italy.’5 The next Kunstkammer inventory, from 1737, describes the figures as John the Baptist, Saint Peter and two ancient poets crowned with laurel wreaths.6 In 1752 and 1753 Saint Peter and the two laurel-crowned poets served as the models for mezzotints by Valentin Daniel Preisler (1717–65).7 [fig. 6-8] The three prints were part of a series of prints of selected paintings from the Kunstkammer. Preisler lists no titles that might serve to indicate the identities of the men. Charles Le Blanc’s 1854 inventory of prints, Manuel De L’amateur D’estampes, identifies the two poets as ‘philosophers’.8 The two figures are first identified as Homer and Virgil in the hand-written catalogue compiled by the painter and museum professional professor Johan Stroe (1805–65) to record the collection at Fredensborg Palace (1848), where the series had arrived in the 1820s after the dissolution of the Kunstkammer.9

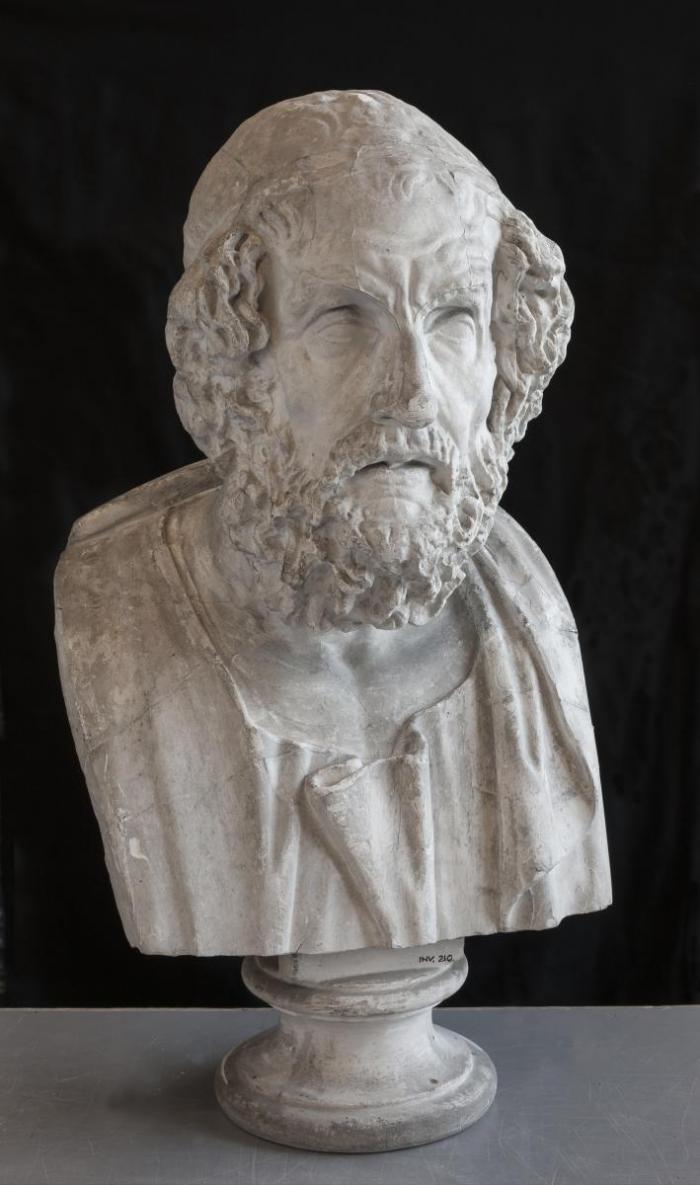

Stroe’s keen eyes presumably spotted the dim, blind eyes that could only belong to Homer. Identifying the companion piece as a painting of Virgil seems natural because Virgil’s writings represent a Roman equivalent or continuation of the Homeric literary tradition. Perhaps Stroe had also noticed the obvious physical similarities between the poet-philosopher appearing in Troppa’s painting and a particular type of portraits of Homer dating back to Hellenic Greece. Appearing in several variants from the eight century B.C., this type depicts Homer as blind, somewhat stooped, with a narrow nose, eyebrows raised and a very wrinkled forehead. The Royal Cast Collection holds a plaster copy of one such marble bust.10 [fig. 9]

As regards the identity of the two Biblical characters, the older, white-haired man is easily recognised as Peter, disciple of Jesus, because of the keys. The inventories and literature identifies the other Biblical character as, alternately, John the Baptist, Saint John the Apostle, Saint John the Evangelist or Saint Phillip.11

Past research

If we turn first to the most recent research within the field, Francesco Petrucci mentions a range of paintings by Troppa in an article in Prospettiva (2012), inscribing the artist among the Tenebrists of Rome from the second half of the seventeenth century.12 Petrucci concurs with the identifications of Homer, Virgil and Saint Peter, but believes that the fourth figure is a depiction of Saint Phillip. Petrucci dates the paintings around 1665-68 and links them to two other half-length portraits by Troppa: Saint Jerome Reading, which appeared on the art market in Rome in 2008, and Saint Paul, housed at the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.13 Since the publication of Troppa’s paintings in Harald Olsen’s Italian Paintings and Sculpture in Denmark from 1961, scholars have shown little interest in Troppa’s paintings in the SMK collection.14

It is possible that other, similar series by Troppa’s hand existed. The art market recently saw the emergence of a penitent Saint Peter whose dimensions and iconography were very similar to SMK’s paintings.15 A small version of Homer painted on panel has also surfaced on the art market.16 This may be a preliminary work or sketch for the SMK painting, but it could also be a fully finished work of art in its own right.

About the artist

Born in 1637 in the small village of Rocchette in the Sabine Hills of Lazio, Girolamo Troppa spent his youth in Rome. A wealth of commissions took him around Lazio, but also to Umbria, Ferrara and elsewhere. He is known to have resided in Rome from 1656 onwards, and the style evident in the works from his early career suggests that he was trained at the workshop of Pier Francesco Mola (1612–66).17 It would appear that the years 1668–69 were busy and prosperous for Troppa. In addition to the aforementioned six paintings bought by van Haven, we know from accounts that Troppa worked for cardinal Chigi at his Roman residence, Palazzo Odescalchi, in 1668.18 Here Troppa did a ceiling mural featuring Flora surrounded by putti, closely pursued by the cold spring wind, Zephyr, which according to Ovid was Flora’s husband. That same year Troppa also did two religious paintings for the Church of Saint Joseph (San Giusepe) in Ferrara. Comparing all these works forms the outline of an artist greatly influenced by his master, Pier Francesco Mola.19 However, things are not quite that simple, for throughout his life Troppa remained a chameleon in the manner of his painting, capable of adapting and appropriating the style of another master.

Troppa worked as a muralist, an easel painter and as a draughtsman, with the churches and the patrician families as his key patrons. In recent years art historians such as Erich Schleier, Zsuzsanna Dobos and Francesco Petruzzi have worked on establishing, confirming and refuting attributions, aiming to establish an oeuvre that appears, as yet, to be very comprehensive.20

Troppa’s colours

Troppa’s ‘Four Philosophers’ are characterised by a restricted, harmonious palette comprising only a few colours. They also display a markedly sculptural approach to the draperies, one in which the individual folds accentuate the rhythm of the composition. Troppa was clearly partly bound by the iconography of the era as far as the colours of the garments are concerned. Having said that, it is striking to notice how each painting has its own harmonious palette even as the paintings taken as a whole display a sophisticated colourism in which the blue-black sky with the moonlit clouds establishes a common underlying motif. Similarly, the reddish-brown ground common to all four paintings also contributes to the sense of an overall unity. [fig. 10] This general impression is strengthened by the local colour of the voluminous robes worn by the four figures: these colours share the same degree of saturation and tonal intensity, which also serves to connect and unite the series. Troppa seems to be oriented towards the particular mode of colour which the art theory literature of the age calls unione – a harmonious unity of tone and colour, a fusion of all the component parts of the picture to form a congruent whole that still offers scope for those contrasts of light and shadow required by space-defining chiaroscuro.21 [fig. 11-13]

Saint Peter

Sheltered by an outcrop of rock, overlooking the restless sea, we see Saint Peter wringing his hands, eyes turned heavenwards – an iconography typical of this era’s depictions of ‘Saint Peter Penitent’.22 The literary source of the scene appears in all four gospels of the New Testament, which give almost identical accounts of an episode from the Passion in which a fearful Peter betrays Christ three times in the gateway and courtyard of Pilate’s house.23 When Peter realises that Jesus’s prediction, ‘this very night, before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times’, has just come true, he cries tears of despair and repentance. The weeping Saint Peter was not just a model image of remorse and penitence within the Catholic church.24 During the Danish Baroque era, particularly under the reign of Frederik III, the teachings of Lutheran orthodoxy were closely associated with the concept of ‘pønitense’. The road to salvation was paved with penance and atonement, remorse and conversion.25

Saint Philip or a Saint John?

The left hand of the figure points in the direction in which he is moving, while his eyes and face is directed backwards, towards rays of sacred light in the sky. The iconography of this figure is less firmly determined, as red robes of this kind could be worn by several different Biblical characters in the paintings executed around this time. The same holds true of the cross carried in the figure’s right hand. Even so, it seems unlikely that the figure is a depiction of Saint Philip: the cross seems to be a reed cross, which points towards the iconography traditionally associated with John the Baptist.26

Might Troppa’s painting be a depiction of John the Evangelist? Given the absence of his traditional evangelist symbol, the eagle, this is unlikely. Might it then be the older evangelist John, who was exiled to the island of Patmos, where he wrote down his apocalyptic visions? This too is unlikely: he would be wearing a white cloak and the heavens would open to reveal a vision of the Virgin on a crescent moon.

The Spanish painter-writer Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), who was father-in-law to Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660), provides very accurate iconographic instructions in his art treatise El Arte de la Pintura (1649).27 Pacheco draws on Italian, Spanish and Latin sources for his detailed instructions on how artists should portray a given holy figure. His directions on how to correctly depict John the Baptist matches Troppa’s portrayal well.28

Pacheco writes in great detail about the iconography of John the Baptist.29 He should be portrayed as a man between 29 and 30 years of age, for that was when he found his calling and began to preach, i.e. the time when he left his parents behind in order to set out into the wilderness to live as an hermit. Alternatively he should be portrayed as a mature man, ‘when the heavens noted him with remarkable splendour and he began to preach about the regime of the heavenly kingdom and the coming of our Saviour on the banks of the river Jordan’.30 According to Pacheco there is nothing wrong with artists adorning their paintings of John the Baptist in the traditional manner by attiring him in a purplish cloak as a symbol of his glorious martyrdom.31 Pacheco recommends that John the Baptist should be depicted with the cross-staff as his attribute, for just as Jesus was always aware of his impending martyrdom on the cross ever since childhood, so too was John the Baptist. Hence he always carried the cross with him, using it as an object of contemplation and meditation, Pacheco states.32

Horace and Ovid or Homer and Virgil?

In his portrayal of the two poets, Troppa appears to have observed a commonplace iconography for depictions of poet-philosophers; an iconography whose written basis may be Horace’s statements about the appearance of genius.33 In Ars Poetica Horace states with thinly veiled satire: ‘Because Democritus thinks natural talent (ingenium) is a greater blessing than wretched art and bans sane poets from Helicon, a good many don’t bother to cut their nails or beards, but seek solitary places and avoid baths’.34

Ever since antiquity, Homer has been regarded as the author of the two epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey, the first of their kind in European literature. Troppa has painted the fabled Greek poet looking into the darkness with his famously blind eyes, their corneas dull and milky white. Struck by divine inspiration Homer raises up his right hand while his left hand maintains order in the pages of the book he has before him. The book is opened on a page where Troppa’s signature can be read upside-down, pretending to be part of the book’s contents. Homer wears a laurel wreath, as does Virgil. The laurels of glory, honour and eternal fame.

Virgil’s eyes are far more vibrantly alive. Whereas the face of Homer is in shadow, Virgil’s is awash with light; a light that does not come from the sun, for the sky is quite dark. This is a metaphorical kind of light, visualising divine inspiration striking the writing poet. Troppa has signed the open book in this painting, too: the book in which Virgil is writing his epic work. An inkwell and an extra quill stands ready for use, and the poet elegantly brandishes another quill, poised to be put to paper and give expression to the furious energy of inspiration.

The Roman poet Virgil, also known as Publius Vergilius Maro (70–19 BC), wrote the Aeneid, whose form and plot takes its starting point in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Virgil worked on this epic throughout his life while living a secluded life in accordance with the philosophy of Epicurus (341–270 BC). Unlike Homer’s epic poetry, the Aeneid is a national epos: the son of the Trojan hero Aeneas became the mythical ancestor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (14–68 BC). During the Renaissance and the Baroque, Homer’s and Virgil’s epic classics constituted a pan-European frame of reference. Reading these epics were considered part of any fully rounded education.

Parnassus and Heaven

Seventeenth-century painting offers several examples of series depicting major poets, but series in which poets appear alongside Biblical characters do not appear to be common.35 Who might have inspired Troppa, and why choose these particular pairings? One of the visual sources that may have been accessible to Troppa is Raphael’s depiction of Homer and Virgil seen in the fresco The Parnassus (1510–11) in the Stanza della Segnatura. [fig. 14] Today, this room of frescoes by Raphael is part of the Vatican Museums, but it originally served as the private library of Pope Julius II.36 The vaulted ceilings feature female allegorical figures of the four ‘faculties of the spirit’ which also served as the ordering principle of the library: Theology, Justice, Philosophy and Poetry. On the walls below, Raphael painted large figure compositions to illustrate these faculties. Standing side by side, Homer and Virgil are among the poets peopling The Parnassus, where the natural centre of attention is Apollo surrounded by the muses. Where Homer and Virgil are representatives of Poetry, the penitent Saint Peter and Saint John the Baptist represent Theology. In Raphael’s La Disputa Saint Peter holds a prominent position in Heaven, where he is the first in the row of disciples. [fig. 15] Saint John the Baptist flanks the haloed Christ with the Virgin on the other side.

Visual sources

Ancient philosophers and Biblical figures were common motifs in mid-seventeenth-century art.37 Around this time, Rome was infused by Neo-Stoic thinking, and painters created idealised portraits of philosophers and epic narratives about the lives of ancient thinkers.38 Painters such as Salvator Rosa, Poussin, Pietro Testa, Il Grechetto, Pier Francesco Mola and Domenico Fetti are examples of this. The concept of virtú (virtue) and moral-ethical integrity were central themes. These artists point back to the works of other artists, especially Giuseppe Ribera’s exemplary portraits of philosophers, which they would have been able to see in Naples and which were also disseminated via copies and Ribera’s pupils.39 In addition to Rome and Naples, the centres for Neo-Stoic motifs also included Venice and Genoa.40 Giuseppe Ribera’s (1591–1652) Le Poète, an etching from 1620–21, may also have inspired Troppa.41 [fig. 16] Troppa’s master, Pier Francesco Mola, is believed to be the creator behind a painting in Galleria Palatina in Florence featuring a poet that also shares many traits with Ribera’s print.42 The Royal Collection of Graphic Art at SMK is home to yet another depiction of a poet-philosopher that includes a small genius handing the main figure his pen and inkwell. [fig. 17] Being a copy after a drawing by Ribera, this picture demonstrates how inventions might not only be disseminated via engravings, but also via other artists’ collections of copies.43

Among the artists that Troppa learned from we find Salvator Rosa (1615–73). At this time Rosa lived in Rome, and he too worked with the subject of philosophers in his art.44 His chief ambition as a painter was to create sublime art and paint sublime motifs. What, then, did Rosa regard as sublime motifs? They might include ancient philosophers such as Democritus, Diogenes or Plato, but also Christian hermits and Church Fathers such as Hieronymus and Augustin – characters who would, for certain periods of time, seek out a solitary existence where virtues such as persistence, self-restraint, asceticism and the concept of doing one’s duty in the world were prime concerns. The objective was to achieve a sense of inner freedom and balance of mind and body. Hermits, Church Fathers engaging in self-imposed meditation or holy figures seeking penance and forgiveness for their trespasses were popular motifs at the time.45

All of these examples show the poet-philosopher as a pensive figure weighed down by a melancholy frame of mind. Troppa’s poet-philosophers are different – they see the light. They have just been struck by a brilliant idea! In Troppa’s work, poetic inspiration – the bright, enrapturing flame of creativity – has been made the main theme.

Fiery inspiration

Raphael’s Parnassus shows Apollo and the muses as the centre of a group that includes Homer, Virgil and a range of other poets from the past and from Raphael’s own time. In Greek mythology, the all-knowing and omnipresent muses are the goddesses of inspiration; patron deities of music, poetry, art and science and of those who practice these crafts. They resided on Mount Helicon and on Parnassus at Delphi, and their mother was Mnemosyne, goddess of memory. Their particular dual gift to poets was that of granting moments of inspiration while also providing them with the prophet’s intuitive, lasting insight into past and present; the special trait that enabled the most gifted, such as Homer, to recollect a loftier, ideal world, thereby reaching sublime heights in his art.46

We need to go all the way back to the pre-Socratic philosophers to trace the origins of the concept of ‘divine inspiration’. Democritus invented the designation, describing it as a form of ‘enthusiasm’.47 Plato adopted the concept, evolving it into a ‘poetic possession’ or ‘poetic madness’. In the dialogue Phaidrus, Plato has Socrates say that only he who writes poetry while ‘not in his right mind’, meaning in the throes of a madness inspired by the gods, can create sublime art.48 According to Plato, four forms of divine madness exist: prophetic ecstasy, sent by Apollo; ritual madness, sent by Dionysus; poetic madness, imparted by the muses; and erotic madness, caused by Aphrodite and Eros.

In the early dialogue Ion, Plato states that the good poet, whether epic or lyric, does not create great art simply by virtue of their professional skill, but as the result of musical inspiration and ecstatic divine possession.49 This image persisted throughout Plato’s writings. In his late dialogue Laws he states that when a poet is inspired by the muse he is not in his right mind, but like a fountain that allows everything that comes into his head to flow out freely.50 Plato sees the poet as someone who creates art in a rush of inspiration, out of the blue, without deliberation or awareness of what he is doing. The flames of inspiration are borrowed for a brief time only, and on the gods’ sufferance.

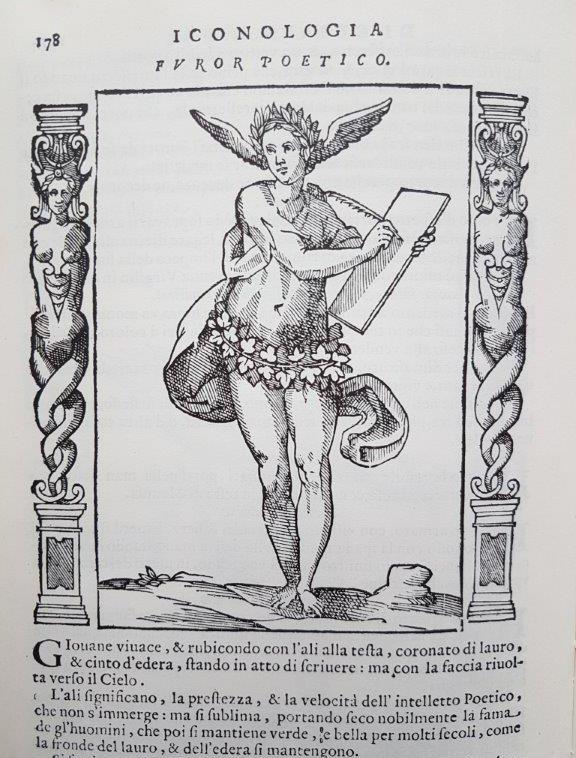

Perhaps Troppa had this state of Platonic furor poetico in mind when conceiving the idea for his poet-philosophers. Troppa depicts the blind and seeing poet equally lit up by the fires of divine inspiration. Perhaps Troppa did not know Plato’s work directly, but that is of no matter, for Plato’s thoughts permeated the art theory writings of the Renaissance and the Baroque. One might, for example, point to Vasari’s mention of Michelangelo in Le Vite, where concepts such as terribilità and furore are brought into play.51 Or one might look at how the idea of Platonic Furor Poetico was visualised in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia – a book that Troppa certainly knew. [fig. 18] Cesare Ripa’s personification of poetic inspiration is shown in the act of writing, his gaze directed to the heavens. He wears red robes and a laurel wreath, symbolising the flame of inspiration and eternal fame.52

Troppa’s ‘4 portraits of ancient philosophers’, Homer, Virgil, Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter Penitent, can be regarded as the chief representatives of the ‘faculties of the spirit’ Theology and Poetry and as visualisations of divine inspiration in Christian and ‘Christianised’ ancient versions. With his four figures, full of pathos, Troppa has visualised the Platonic concepts of prophetic and poetic inspiration. ▢

Post scriptum: The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the Novo Nordisk Foundation for its support in the form of a research grant that rendered this work possible.

The to image is a detail of Girolamo Troppa: Vergil, The National Gallery of Denmark, see fig. 1.