Summary

The article analyses the process that made the barber John Christensen a celebrated figure on the Danish interwar art scene over the course of just a few years, as well as the conditions that prompted his marginalisation in art history from 1950. The text points to a vein of ‘Primitivist’ art, supported by art institutions, and to an ever-growing awareness of working class audiences and the labour movement as important factors within the field of art. Taking its starting point in John C. and a number of artists associated with him, the article proposes a more pluralistic view of the art created during this period; a position that offers more nuances than the widespread view of two irreconcilable blocks: avant-garde and tradition.

Articles

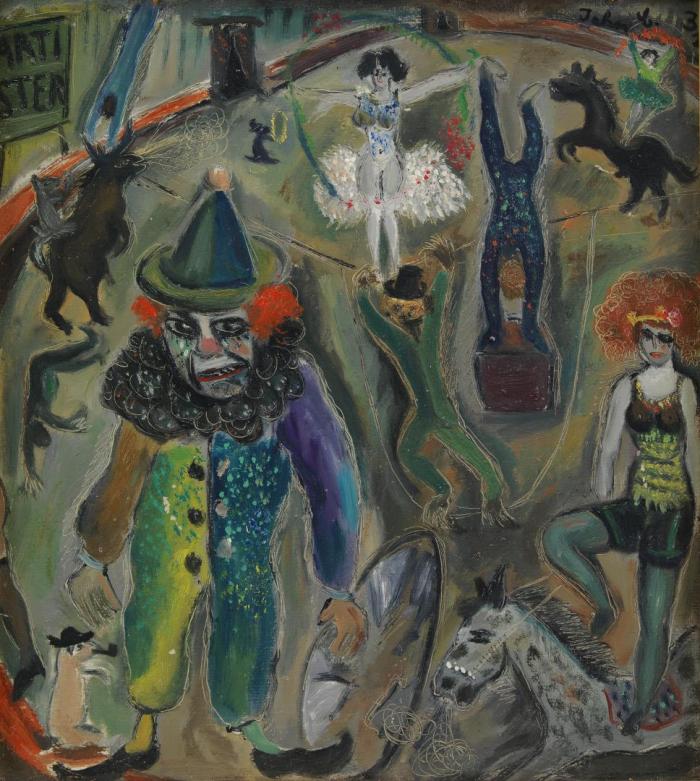

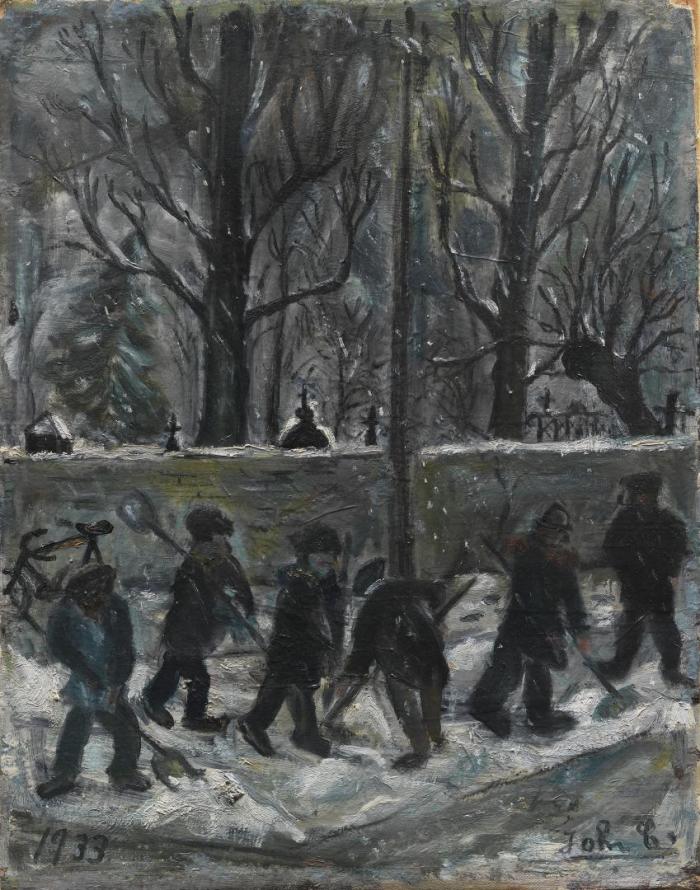

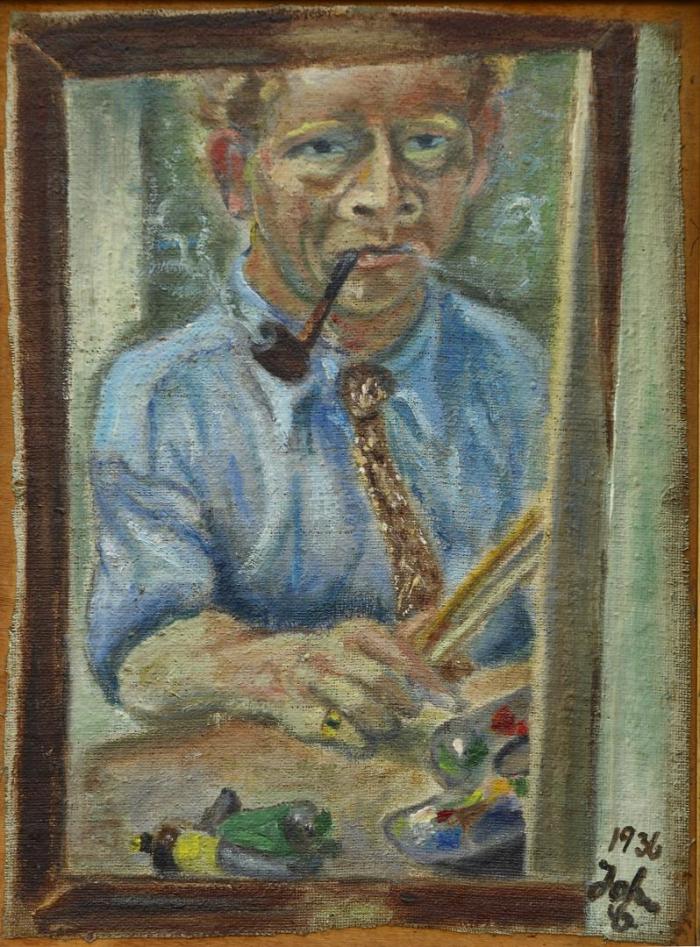

In 2011 Statens Museum for Kunst (the SMK) acquired Circus Artists in the Ring, 1932, thereby making it the fourth painting by John Christensen to enter the museum’s collections. The first, Snow-Clearing from 1933, was received as a donation in 1940, whereas the other two, A Lady Wearing a Hat. The Artist’s Wife, Dagny Marie Christensen from 1935 and Self-Portrait from 1936, were purchased in the 1980s. The museum collection also encompasses thirty-nine of Christensen’s works on paper; the first such purchase was made in 1932, the most recent in 2002. All of these works are almost permanently in storage, as are the more than 150 other works by this artist owned by various Danish museums.1

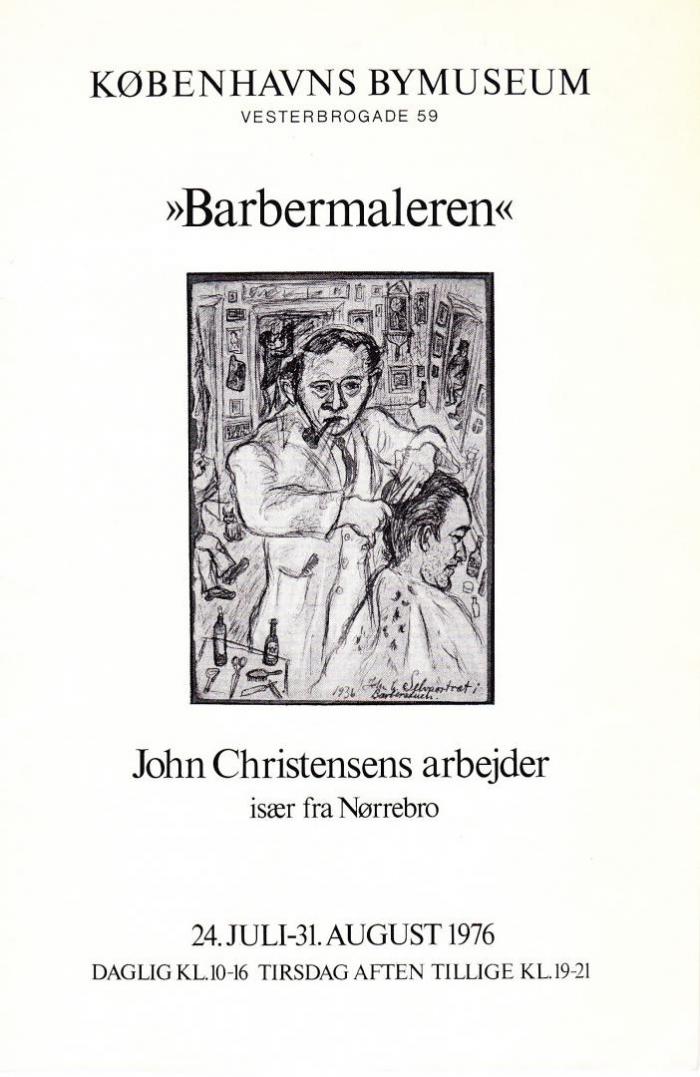

Yet even though the museums keep his work stowed away, the name John Christensen is not unknown by the public. It rings a bell with many people – especially if you add the moniker ‘The Barber Painter’. Over the years the artist has been the subject of numerous journalistic articles, often focusing on the colourful circle of characters that surrounded his barbershop in Kapelvej in the Nørrebro area of Copenhagen where he found much of his subject matter. In 1987 he was even the subject of a new play.2 However, in art history he is largely consigned to footnote status;3 reference works about the 1930s – which are usually constructed as narratives about the irreconcilable opposing forces of avant-garde art (or modernism) versus tradition – leave him floating without any firm context, possibly as a footnote associated with the Corner tradition, and often in connection with the concept of ‘hjemstavnsmaleriet’ – paintings of home, hearth and one’s immediate surroundings.4

The objective of the present article is to analyse how the barber John Christensen (hereinafter John C.) became part of the art scene of his day: to chart the process that, within the span of just a few years, transformed this barber into an artist of almost cult-like status, celebrated by critics from every camp and compared, upon his death in 1940, to great figures of art history such as van Gogh, Chagall and le Douanier (the customs officer) Rousseau.

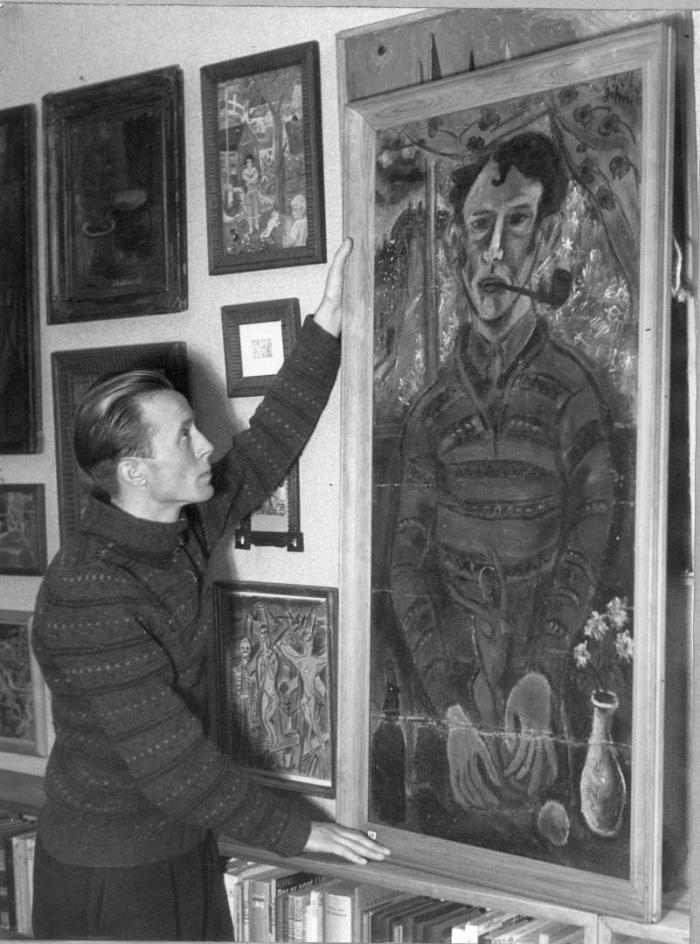

More than seventy years have passed since John C. died. Almost all eyewitnesses and fellow artists are now gone,5 and apart from a single binder of cuttings we have no archive pertaining to his work, nor indeed any major primary materials apart from the works of art themselves.6 In order to analyse the process that made John C. an artist it is, then, necessary to take one’s point of departure in materials and information from people associated with him, who can shed light on his sales and alliances, and in printed materials that can tell us about his exhibition activity and reception. Particular emphasis will be placed on the questions of who bought works from the artist, thereby supporting his work, how and for what reasons he was presented to wider audiences, and what agendas the various stakeholders had.7 The objective is to identify and present an overall context that will make it possible to consider the artist and his work in ways that are more meaningful than the simpler angle suggested in the above. [fig.1]

Let us begin by establishing certain facts about our featured artist: Born in 1896, John C. was the son of a tailor. He grew up in the St. Kongensgade neighbourhood of Copenhagen as the oldest in a flock of siblings that eventually counted twelve children. He attended the Sølvgades Skole, and having completed his compulsory military service he trained as a hairdresser in Haslev. Thus, it was hardly written in the stars that he would become a well-known figure on the Danish interwar art scene.

In 1920 he acquired a barbershop in Roskilde, and in 1921 he married Dagny, a shop girl from the store where he bought his tobacco. In 1922 the newlyweds returned to Copenhagen, where John C. operated a barbershop in the basement of Kapelvej 7A in the Nørrebro area until 1937.8 The family lived in a one-bedroom flat in the same building until 1935; at this point John C. received the Villiam H. Michaelsen grant and spent the money on moving to a garret flat in Fyensgade 4, still in the neighbourhood of Nørrebro and still overlooking the Assistens churchyard. In 1937, having received the Oluf Hartmann grant,9 he bought a small holiday cottage in the village of Vridsløsemagle near Taastrup and sold his barbershop in order to devote himself entirely to his career as an artist. On 2 January 1940 he died of cancer after a relatively brief period of illness.10

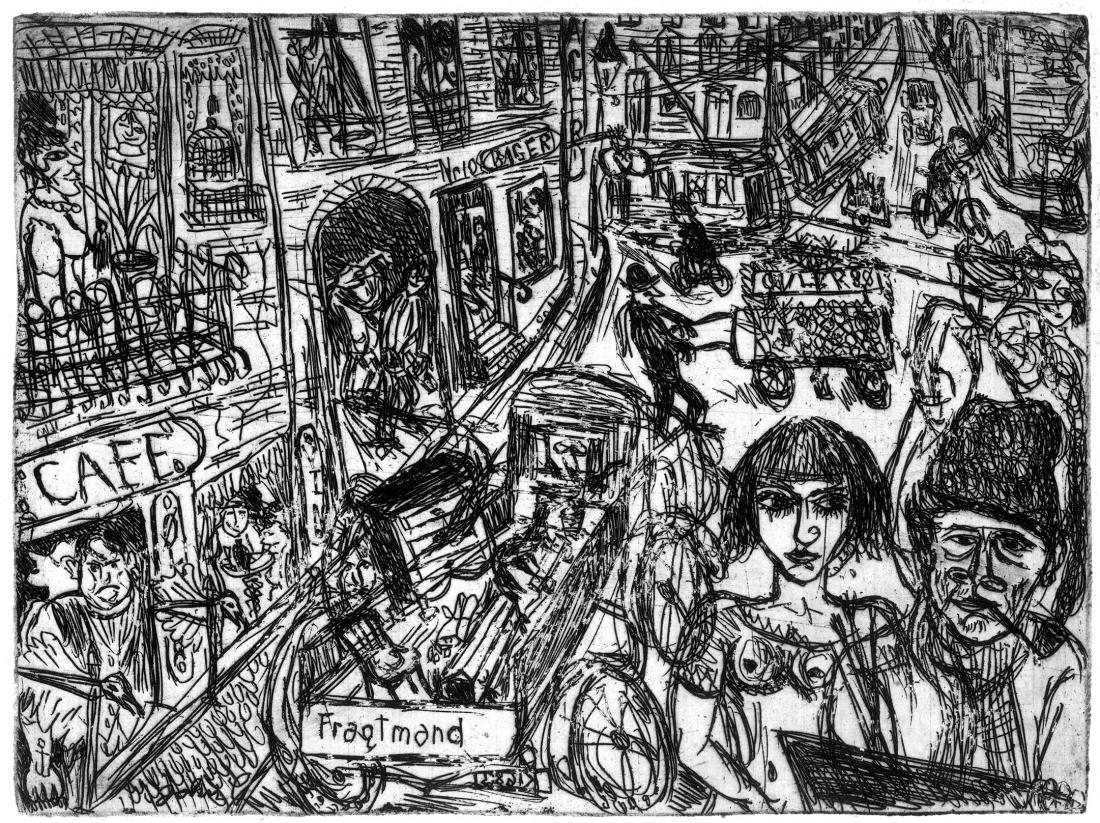

The art critic Poul Uttenreitter, who wrote about John C. in the series Vor Tids Kunst (Art of Our Time) and also knew him personally, states that John C. began working as an artist around 1923. The claim is corroborated by the fact that the oldest known dated art work by John C. is a small crayon portrait of his daughter Mussi from 1924. The next year saw the creation of both drawn and painted still lifes. Tracing John C.’s body of work becomes much easier from 1928 onwards, for by this time he exhibited his work prolifically – at the Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling (KE) (The Artists’ Autumn Exhibition), at art dealers and as part of the artist group Koloristerne (The Colourists), of which he was a founding member in 1932 and headed as chairman from 1935 until he died.11 Despite the brevity of his career John C. left behind an extensive body of work, most of which is scattered among private collectors, but fortunately for the purposes of this article many of these works are still owned by descendants of the collectors who originally acquired them. [fig.2]

Entering the art scene

Exactly what prompted John C. to decide to try to exhibit his art cannot be conclusively ascertained. He may have been encouraged to do so by artists who frequented his barbershop. We certainly know that he knew Søren Hjorth Nielsen at an early stage; Hjorth Nielsen painted John C.’s portrait in 1928, and he was among the guests invited to the parties frequently held in the barber’s home.12 John C. himself pointed to Jens Søndergaard as a role model. Their friendship may well have gone back a long way; indeed, Søndergaard lived in Nørrebro for some time during the 1920s.13

John C.’s debut at the KE in 1928 – his entries included a self-portrait and two funeral scenes – did not attract much attention. However, in the years that followed he had a number of solo shows, and the press gradually began to take note and attend his exhibitions even though they took place at very humble venues. Given that John C.’s ‘emergence’ took place during a time where discussions on social art, working-class art and democratisation accompanied much of what went on within the realms of culture, one might easily imagine that the workers’ movement and far-left groupings were main forces behind the promotion and elevation of this barber, this autodidact artist from working-class roots. However, closer scrutiny of the contemporary reception of John C. paints a far more complex picture.

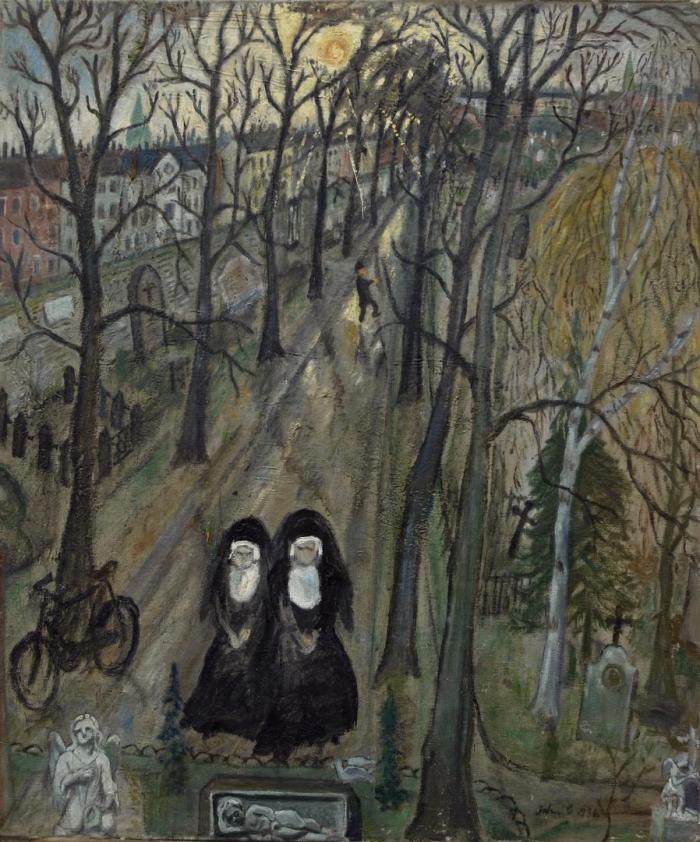

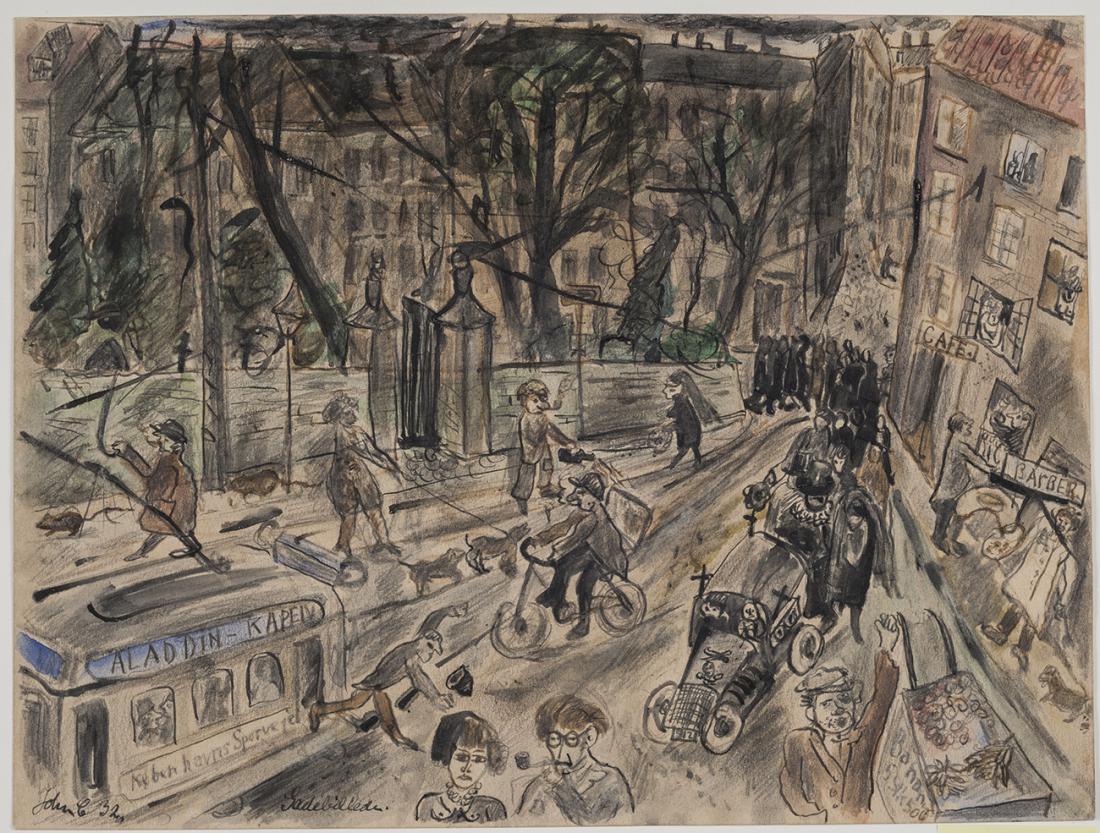

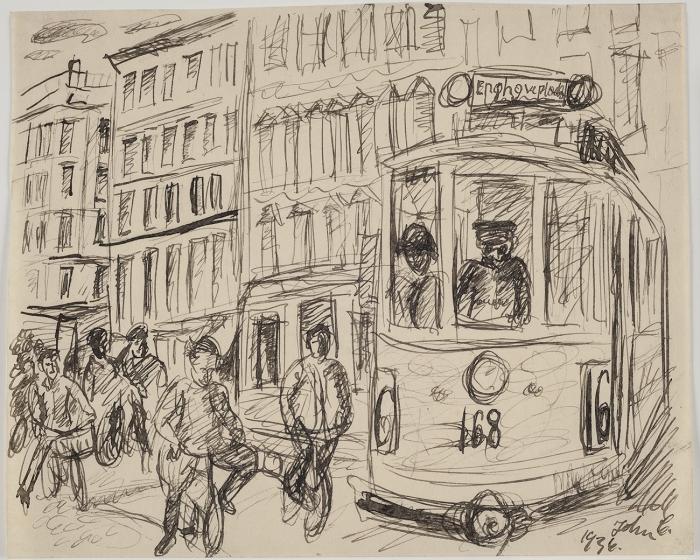

The tabloid newspaper B.T. was among the first to call public attention to the artist. When, in March 1929, he exhibited his work in the then recently opened gallery Tjørnelunds Kunsthandel in a basement in Gothersgade,14 his work attracted the attention of the writer Anna Linck. The small exhibition consisted of paintings, drawings and watercolours depicting e.g. street scenes, funerals and circus motifs, and Anna Linck emphasised that John C. was an artist who had, despite vestiges and signs of inspiration from multiple sources, his very own, distinctive palette and grip on colour.15 One of the regular critics with B.T., the painter O.V. Borch, was in attendance when John C. exhibited at Kinagaarden in the Vesterbro area of Copenhagen the following year. Unimpressed with John C.’s technical skill, Borch recommended that he should improve himself by studying artists as widely different as Breughel and Chagall. The fact that Borch’s verdict was nevertheless positive rested on three qualities: the artist’s sense of humour, his natural gift for art, and his ability to convey entirely new subjects through the medium of art. In his summing up, he stated that: “In some paintings of the Kapelvej road with the Assistens churchyard in the background and the slow-moving Line 8 tram as the focal point of the picture he successfully conveys some of the distinctive, brooding sombreness and mouldy atmosphere that shrouds this peculiar neighbourhood.”16 Note the use of words such as “mouldy” and “peculiar”. As many later reports and statements will make clear, the Kapelvej neighbourhood was a world in which few of the main movers and shakers of the cultural scene of the time felt at home. [fig.3]

The first sale

It is hardly possible to provide an exact answer to the question of who first bought a work of art from John C. The fact that names of private owners of certain paintings appear all the way back to his first solo show does not necessarily mean that those works were sold to them. The engraver Max Müller claims to have been the first to buy from John C. – apart from an art dealer that we can only assume was Henning Larsen.17 However, Müller may have to share that distinction with not only Larsen, but also with a bicycle courier called Robert Jacobsen. Yes, indeed: that messenger boy was none other than the Robert Jacobsen who went on to become a famous sculptor, known as “The Great Robert”, but neither he nor John C. would have had any inkling of the greatness that laid in wait for him when they first became acquainted in the early 1930s. Some years would still go by before a young Jacobsen began experimenting with sculptures made out of wood and scrap iron back in his parents’ basement, and almost ten years would pass before Jacobsen had his first exhibition.18 At the time of John C.’s death Robert Jacobsen owned at least six works by him – an early oil and five watercolours19 – but many more had passed through his hands. Robert Jacobsen has later related how he collected a number of paintings by Søren Hjorth Nielsen, Victor Brockdorff and John C. while living at his parents’ home back in the early 1930s – his objective was to sell the paintings on in the second-hand shop he ran with his mother, but these art dealings did not yield the financial results he had hoped for.20

As a young errand boy, Robert Jacobsen happened to pass by Henning Larsen’s gallery (Henning Larsens Kunsthandel), which was housed in modest premises in Vognmagergade, and he grew fascinated with the motley crew that gathered there to play cards and discuss art. The group included Søren Hjorth Nielsen, Karl Bovin, Kaj Ejstrup, Eugène de Sala, Helmuth Thomsen and Max Müller. Robert Jacobsen befriended Max Müller, who was around the same age, and when John C. had an exhibition at Larsen’s gallery in 1931 he helped type up the catalogue inventory. However, Jacobsen’s most vivid memory of that event concerned the unconventional method of presentation: the pictures were hung so close together that they covered all the surfaces of the entire room – walls and ceiling alike. He recalled that the cost of a good drawing by John C. was around a couple of kroner, or could be acquired for a sandwich.21

Robert Jacobsen shared his memories of the time with the journalist Ernst Mentze in 1961, many years after the events took place, but his statements are corroborated by other sources, and there can be no doubt that early buyers got their John C. works at very low prices. In an interview with Henning Larsen conducted by collector Vagn Nielsen in 1949, the exhibition in the summer of 1931 was described as follows:

“HL also stated that this exhibition, which had been staged in a space smaller than any of the rooms found in the gallery’s current address in Kompagnistræde, had featured so many drawings that he and John hung them on the ceiling, too. Then they put in a large armchair that visitors could recline in to look at the pictures. HL took over 200 drawings after this exhibition, and in order to help John he gave many of them away to special customers and sold the rest at five or ten kroner apiece.”22

Max Müller himself stated that he paid DKK 10 for the painting Audience from 1931 and DKK 15 for The Performer’s Box; supposedly prices from the higher spectrum of the scale,23 whereas Henning Larsen’s prices were generally even lower: “Henning Larsen bought 200 pictures by John C. in exchange for some old furniture; he sold the drawings at 0.50 kroner a piece. He took the pictures out of their frames in order to make them easier to sell. Robert Jacobsen bought at this price.”24 This is to say that Max Müller was among the first to buy art by John C., apart from the art dealer himself, and all available evidence suggests that he was the first to establish a proper John C. collection; this eventually numbered more than forty works that he hung from floor to ceiling in his room in his parents’ house.25

The painting barber

The early exhibitions made no mention of the fact that the artist was a barber, or that his artistic endeavours took a barbershop as its point of departure. So it was not this fact that prompted interest among critics, nor did it pervade how they perceived and understood his work. This would all change over the course of 1932.

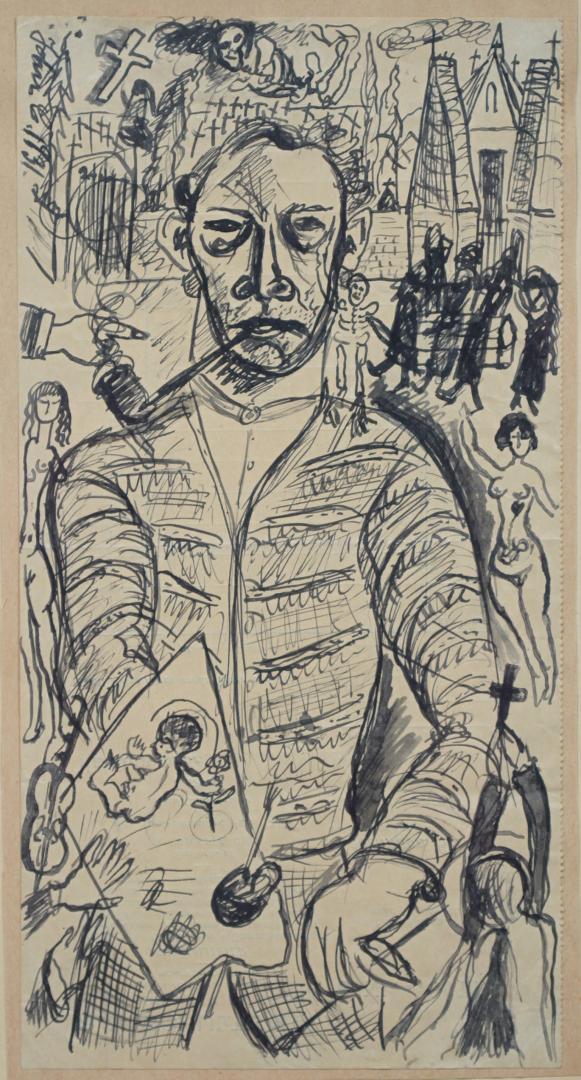

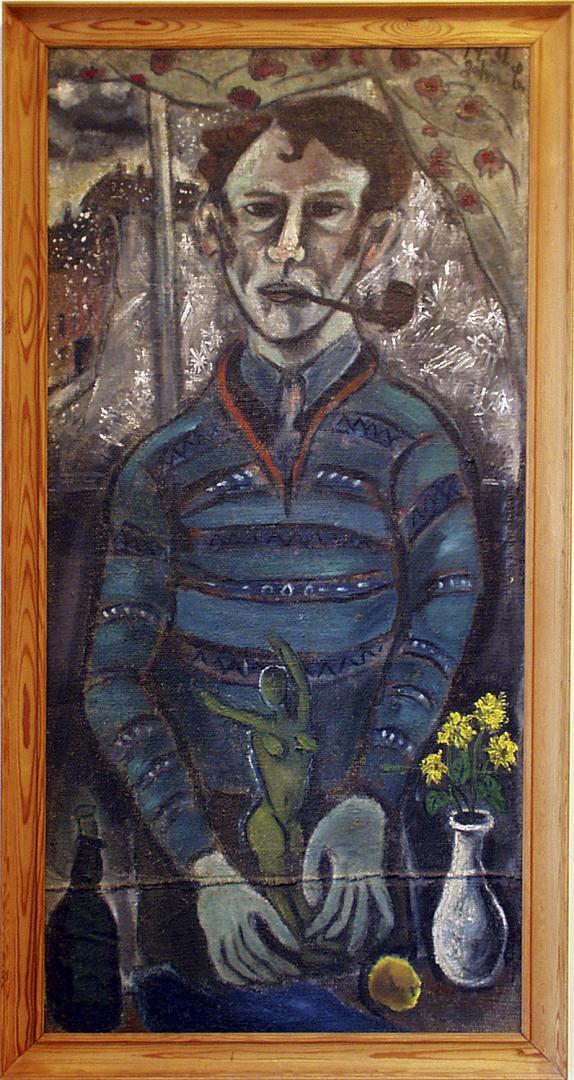

The first step was taken by Preben Wilmann, a critic with the newspaper Social-Demokraten, in connection with a solo show at Kinagaarden in the spring of 1932. Wilmann set up an interview with the artist, during which he pursued two parallel courses of inquiry. One of these focused on the issue of being an artist who works in a working-class neighbourhood and portrays that context in his art. Part of the interview describes the wealth of distinctive people and events that could be found in that neighbourhood, but it also addresses the artist’s relationship with the working class as an audience – and about the fact that John C. prized them above more affluent art lovers. [fig.4] The other main focus of Wilmann’s interview is the question of how the artist’s ideas arise out of his barbershop and his immediate surroundings; how the intervals between clients allow him time to pause, look out the window and draw the wealth of potential subjects that parade past his shop. At the same time, the barbershop is presented as a meeting place and favourite haunt of artists; John C. himself says: “I have some great friends among the painters; they come to my barbershop, and then we discuss art until we’re blue in the face.”

One of the key reasons why Wilmann set up this interview was the fact that John C.’s art had its roots in the city and was an example of “contemporary, vibrant, realistic urban art”.26 Preben Wilmann was originally a painter, studying under William Scharff first, followed by Pedro Araújo in Paris, but from 1920 onwards he also worked as a journalist for Social-Demokraten; for him, this endeavour would gradually eclipse painting as a career. During the 1930s he was a high-profile writer on art, known for his Marxist views, and his critique often constituted contributions to the ongoing discussion on ‘working-class art’ that infused much of the left wing during the interwar years, a time when many believed that art should and would play an important part in recreating society by being overtly political.27

However, this perception of workers’ art soon came under pressure within the Danish Social Democratic Party (Socialdemokratiet), as expressed by Julius Bomholt in his book Arbejderkultur (Working Class Culture), 1932: instead of critical, polemical, belligerent art this book called for a positive vein of art suited to a proletariat on the rise; a kind of art that reflected the movement’s ever-growing power and position in society.

Preben Wilmann engaged in similar thoughts, and in the 1930s he operated on the basis of a dual agenda: partly to ‘update’ the workers’ movement’s understanding and appreciation of contemporary art, and partly to prompt artistic innovation based on inspiration from the workers’ world. This agenda can be clearly felt in his reception of John C.28

In addition to the two main themes of Wilmann’s interview it is also worth pointing out how he introduced a narrative that came to be important to the general view and reception of John C: the narrative about the importance of the churchyard as an existential sounding board for the work, as illustrated by the story of the shock of putting one’s head down into an open grave on a lovely summer’s day. Wilmann’s depiction of John C. came to form the basis for much of the subsequent reception, and he also laid down the foundations for a range of anecdotes that only improved with age, being gradually expanded on and embellished by colourful variations.29

Where soap foams for the sake of art

The interview took place at the offices of Social-Demokraten, where Wilmann had arranged to meet the artist.30 When the artist group Koloristerne held their first exhibition in Copenhagen towards the end of 1932, new facets were added to the barber-artist persona by Christian Houmark, a seasoned journalist with the popular tabloid B.T., who used this occasion to conduct an interview with the zingy headline “Where soap foams for the sake of art”. The setting for this interview was not a newspaper office, but the barbershop in Kapelvej 7A, and from this point on the shop became an almost inescapable part of the context of John C.’s work. In Houmark’s piece the barbershop was presented with great emphasis on its plain, unassuming, but fascinating down-to-earth qualities, which are evoked through references to the “sup of beer” that the interviewer and artist partake of while customers flit in and out, perhaps on their way to a funeral or to “Fat Carl”, the publican of a nearby establishment in order to drown their sorrows. Houmark conveys the impression of a constant throng of people that eventually forces John C. to pin a note on the door and retreat to the back room in order to be able to complete the interview. This introduces us to the back room, where his works are kept, a small space opening up on the inner courtyard. [fig.5]

The interview was accompanied by a photograph showing the artist at work as a barber. John C. used the photograph as the basis for a drawing that was subsequently often reproduced in articles and on catalogue covers; it was even used as a poster. That image undoubtedly helped to firmly establish the barbershop and the barber’s craft as a context for the artist’s work. Houmark also offered other material to supplement Wilmann’s anecdote about John C.’s interest in death, adding a new layer to the theme: his grief over the death of a younger brother. The barber’s ‘bourgeois’ family life – a topic that Wilmann had already touched upon – was now further expanded on as Houmark emphasised Johns C.’s strong admiration and affection for his wife, who represents “Life’s true timbre of Love.” Finally, Houmark emphasised the autodidact aspect of the artist’s work, allowing the artist to express the significance of being self-taught in his own words:

”[…] ‘What pleases me most is the fact that I never learned how to paint; the Academy ruins the young, that’s what I think. Of course we need technique, but first and foremost we must be our own, personal selves […] no, indeed, I am Nature first and in all things, paying no heed to fashions [ …]’.”31

With this, the key features of the popular reception of John C. were firmly in place. Over time, the themes would be accentuated further: the multitudes of local characters coming and going, and the barber’s work as an inspirational setting for the artist’s creativity. Many variations are spun on the theme of the informal amiability that pervades the barbershop, a place where everyone is on a first-name basis, and where immediacy is respected while academic airs are reviled. [fig.6]

Certain aspects would receive particular attention at various points in time; for example, in the second half of the 1930s emphasis was placed on the bourgeois lifestyle that characterised John C. as a private individual: he tends to his business, wears polished boots every day, enjoys his Sunday roast; he is firmly anchored where so many other artists are unmoored. This distinctive identity may serve to set him apart from the many workers in his neighbourhood, but it also, and perhaps more importantly, sets him apart from the bohemian image attributed to other young artists of the day, including Hans Scherfig, Hjorth Nielsen and Aage Gitz-Johansen.

However, even as John C. was described as an anti-bohemian person, his entire neighbourhood was gradually ascribed bohemian traits. Nørrebro became the Paris of Copenhagen, a point that was emphasised by journalists and by John C. himself – for example in a 1935 interview conducted by Dr. Rank from the tabloid newspaper Ekstrabladet, who reported on the state of affairs “out in Kapelvej”, where he met the artist early one morning. John C. counted his blessings to be working as a barber; a profession that allowed him to meet so many people: ”[…] I love people, all people, but especially the people of Nørrebro – there are ever so many wonderful characters amongst them! Nørrebro is the Paris of Copenhagen, mark my words! I shall never leave.”32

In 1936 the newspaper Berlingske Aftenavis paid a visit to “The Colourist John Christensen, Nørrebro’s Parisian interpreter” and saw the magic being made: “In a small basement room, behind yellow curtains before the windows, paintings hang between mirrors, and next to a soap dish the artist’s palette glistens and shimmers with colour. Strange paintings: expressive, grotesque; granite and gutters transformed into scenes worthy of the Arabian Nights.”33

It would seem that the cultural establishment regarded John C.’s neighbourhood as alien territory, frightening and fascinating in equal measure, a potential destination for an “expedition.” As the writer Jacob Paludan put it, a walk around Nørrebro may make you:

“lose yourself in districts reminiscent of those that other large cities parade as dwellings for those who regard suspensions of payment as an everyday event. In such places one finds far too many second-hand stores with far too many neat second-hand clothes hanging outside. Hard bargains are being struck here; behind walls like these the coverlet on the poor man’s bed has been haggled over. But these streets are also home to antiques shops with window displays of blue commemorative plates – Christmas of 1907 – violins and samovars [….]”34

Poul Uttenreitter, who would later become John C.’s biographer, was also somewhat falteringly hesitant when he took his first steps onto the working-class streets of Nørrebro, but was soon introduced to ‘the natives’ and their ways of life by John C., who had to show Uttenreitter that the images from his art – such as the marvellous second-hand shops and distinctive characters such as the old lady walking in the street while holding a birdcage – actually existed in real life.35

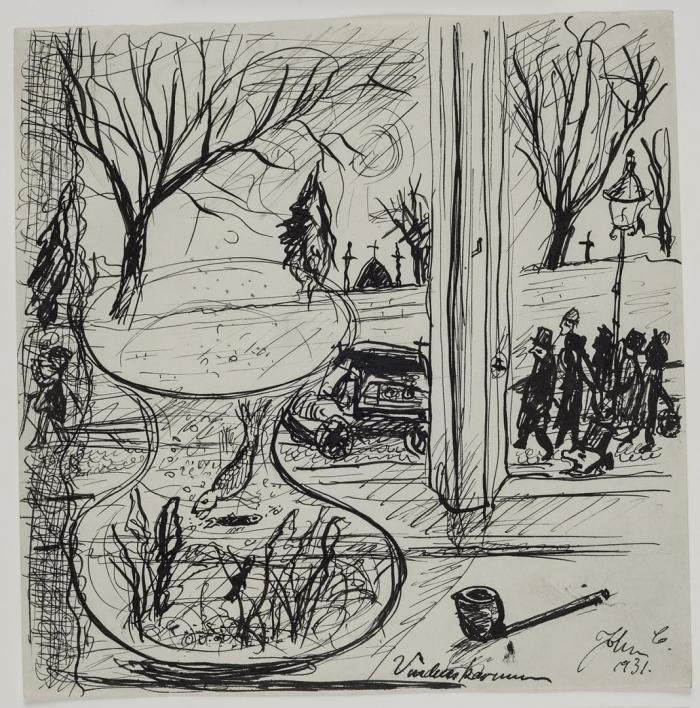

Institutional seal of approval

John C. got his first seal of institutional approval as early as 1932. The SMK made its first purchase of his art at the Koloristerne exhibition that year, acquiring four works for the Royal Collection of Graphic Art: two sketch portraits of Dagny executed using daring angles and cropping, and two drawings of scenes from Kapelvej: the atmospheric Trees by the churchyard wall at Kapelvej (fog) and A funeral procession passing by my window from 1931.36 The latter is characterised by its sheer joy in storytelling and a subtle, gentle sense of humour that is characteristic for much of John C.’s work, as well as by having unbroken lines that vary greatly in thickness – a feature of many of his best drawings – and a somewhat crooked perspective. Finally, here we also find some of the characters that were a recurring trait of his folk scenes, such as members of funeral processions and a pipe-smoking man. The street scene has been drawn as if it were observed through the window of his flat, viewed partly through curtains and a goldfish bowl, and John C.’s pipe, which became something of a signature for him, occupies a prominent position on the windowsill in the foreground. [fig.7]

We have seen, then, that SMK noticed John C.’s art at an early stage; this is also evident from the fact that he was awarded the Villiam H. Michaelsen grant. SMK director Leo Swane was in charge of selecting grant recipients, so when the 1935 grant went to John C., Vilhelm Lundstrøm and Kay Christensen – and the draughtsmen’s associations found it problematic that a grant dedicated specifically to draughtsmen was awarded to three artists who all had painting as their main field of operation – Swane was obliged to publicly explain the reasons behind this choice. He offered the following explanation concerning John C.:

“The third artist, John Christensen, known as The Painter-Barber because his profession as a barber is his main source of income, I have followed for several years, repeatedly viewing his talented drawings at Kunstnernes Efteraarsudstilling at the ‘Den Frie’ exhibition venue. At the book exhibition at Kunstindustrimuseet (now Designmuseum Danmark) I noted John Christensen’s Wessel illustrations with great interest, deeming them the very best there.”37

That same year, another three works were purchased for the Royal Collection of Graphic Art at the Koloristerne exhibition: two quite traditional portraits of children and a watercolour, Quiet Morning by the Wall.38 The latter was mentioned in Leo Swane’s review in Berlingske Tidende, where he said that:

“Those who attend the exhibitions showcasing young artists today will long since have noticed that John Christensen possesses quite extraordinary abilities, a strange freshness of observation, a sense of immediacy that repeatedly takes him right to the core of his chosen subject, and a keen sense of humour that calls forth the amusing and whimsical aspects of those subjects. One example would be his small picture of men working in the snow. But he is also a sensitive painter; watercolours such as those called Rain or Quiet Morning by the Wall are small scenes of great and rich painterly impact.”39

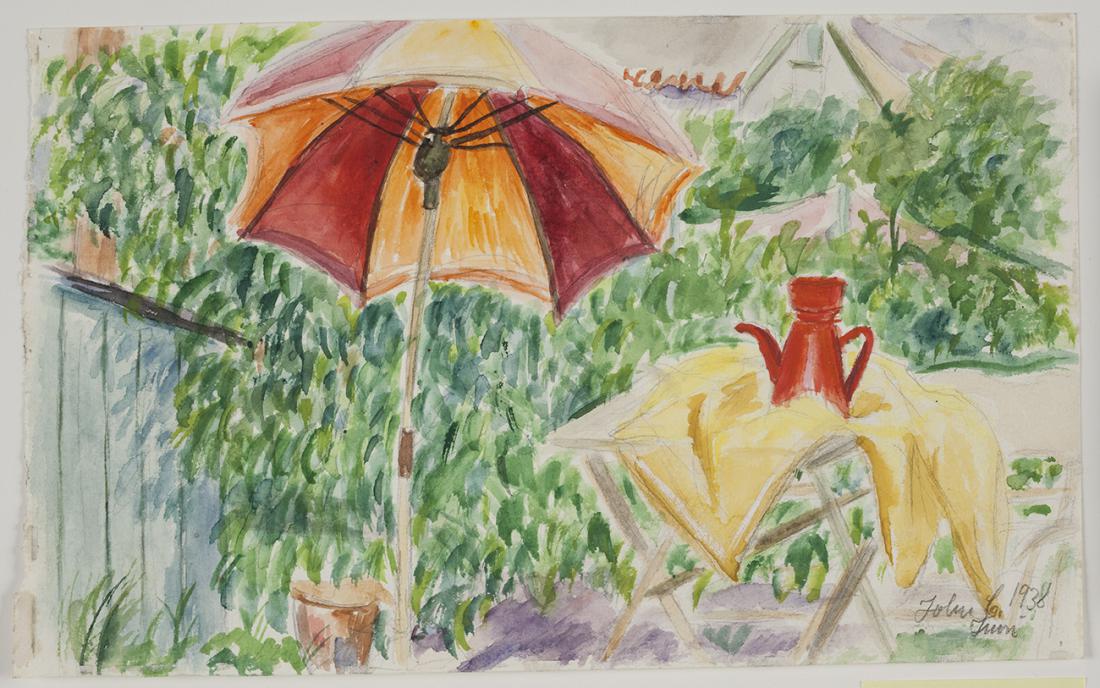

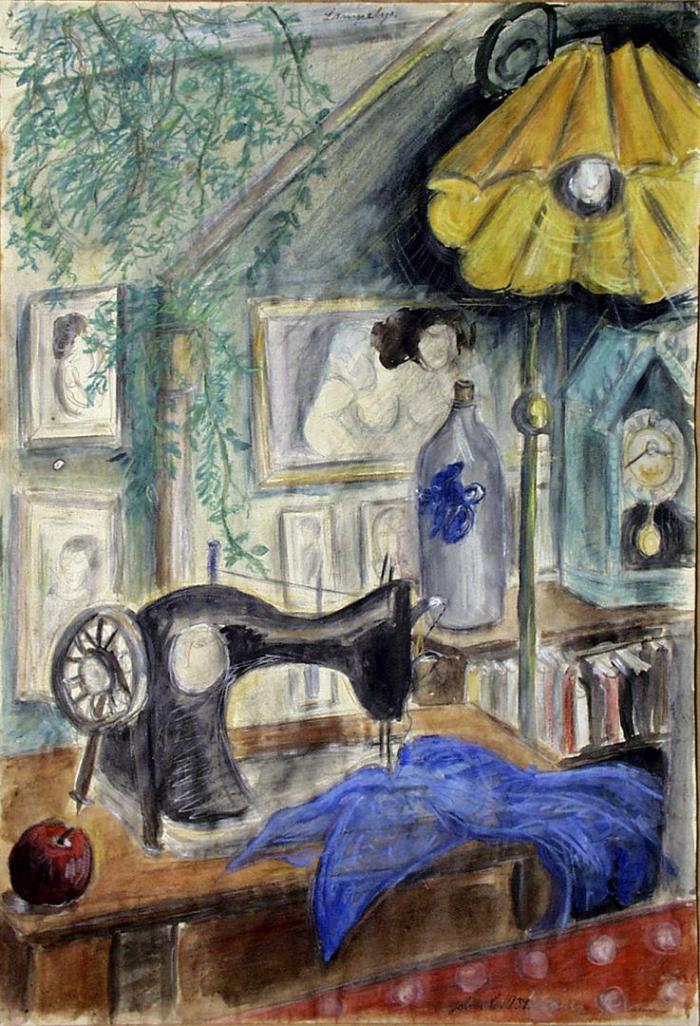

At John C.’s solo show at Arnbaks Kunsthandel in November 1935 the SMK once again sent representatives; they bought a drawing and three watercolours, including the large watercolour Girl with a Sewing Machine, 1934 and Winter Funeral from 1928,40 an early picture which includes many of the motifs that would become recurring traits in his art: a man with a shovel, a priest standing by an open grave, funeral parties, wreaths and a flag. At the exhibition held at the art dealer Mulle Nording in the Nyhavn area of Copenhagen in 1937, the museum bought a drawn portrait of the artist’s daughter Lillian,41 and purchases were also made directly from the artist during John C.’s final years alive, including yet another Nørrebro scene, The Line 16 Tram Turning a Corner, 1936, [fig.8] and two portraits: one of Gudmund Hatt, Geographer and Professor and one of The Painter Helmuth Thomsen. Finally, three works depicting scenes from Vridsløsemagle were also acquired from John C. himself: Whitsun Light, a small, naturalistic painting depicting a road winding into the distance, flanked by characteristic telephone masts and wires describing an arch that adds greater depth to the scene, as well as Laburnums in a Garden and Garden Parasol, idyllic scenes that shine and sparkle with colour, depicting the small garden at the artist’s summer cottage. [fig.9]

No paintings were bought for the SMK while John C. was alive. However, in 1938 he became represented at Ystad Konstmuseum, which received Shadows on the wall. Nørrebro, 1938, as a gift from Hofjægermester Hagemann from the manor of Bergsjøholm,42 and in 1939 Randers Kunstmuseum received Self-portrait, Lamplight, 1938, as a gift from the lawyer Poul Buhl. Finally, in 1939 John C. was added to the collection of Stiftsmuseet in Maribo, which acquired the watercolour October Evening, Nørrebro, 1938 (now owned by Fuglsang Kunstmuseum) from the art dealer Arnbak.

The partnership between Leo Swane and Erik Zahle

The acquisitions made for the SMK took place while Leo Swane was director of the museum. According to Villads Villadsen, Swane effectively dominated the decisions about purchases made at the museum, including those for the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, throughout his time in the director’s chair.43 However, as far as the acquisitions of John C.’s art are concerned, all signs suggest that he was in agreement with Erik Zahle, who was curator at the collection of paintings during part of Swane’s directorship and headed the Royal Collection of Graphic Art from 1933 to 1935.

As has already been quoted, Leo Swane repeatedly wrote favourably about the artist, and he also did so in 1937 when he included John C. in a section entitled “De Unge” (The Young Artists) in the reference work Danmarks Malerkunst (Danish Painting). Here, John C. was given a relatively prominent position as a “concluding vignette”, inserted to ensure that the book would not have a “dead end” – after the Surrealists, in whom Leo Swane saw no artistic perspectives. He chose instead to conclude the reference work by taking “a look at a man who, in the midst of Nørrebro in the heart of Copenhagen, has found Nature – the nature that surrounds us and the one inside all of mankind.”44 His description emphasised the fact that John C. was not spurred on by social concerns, but simply painted “his entire little urban milieu” because it was beautiful in his eyes, and that he – despite having received no formal training – possessed a keen sense for observing the baroque and the humorous, as well as an ability to seek out role models as required, including Harald Giersing and Henri Matisse. Emphasising that John C. was not a socially conscious artist in a political sense was evidently important to Leo Swane. He had no interest in promoting art that had been reined in to serve a political purpose.

We do not know for certain whether Leo Swane knew John C. personally. However, we do know that Erik Zahle did so, at least from 1937, where he made documented visits to the artist in Vridsløsemagle.45 Erik Zahle also made numerous references to John C. in reviews, for example in connection with the Koloristerne exhibition in 1936:

“Those who love contemporary French art have discovered and recognised some of the artistic charm of Paris in the work of this fresh Nørrebro painter. John Christensen can be playfully light and almost too perfectible in paintings such as his self-portrait and certain drawings. However, most of his penmanship and pencil studies evince a strangely convoluted and curly line that gradually, through dogged labour and numerous detours, works its way towards something that is exactly right.”46

A later head of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, Erik Fischer, said about Erik Zahle that he was “young concurrently with the first movement of cultural democratisation”,47 and this is confirmed by Zahle’s writings from the 1930s; a time where he also introduced the art of drawing and printmaking to a wide audience through radio lectures and worked hard to break down the barriers between the general public and the study room at the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, which he believed ought to attract as wide an audience as the public libraries.48 Like Leo Swane, Zahle also felt that it was important to take a stand against the overtly political art of the time. In the catalogue for the exhibition Moderne Bogillustration (Modern Book Illustration), held in 1934 – the exhibition referred to by Leo Swane in the above quote about Wessel illustrations – Zahle made the following comment on the general interest in “social art” in the opening article:

“In our current day and age social art is much talked-about, even though it hardly gives the impression of great longevity; let us disregard such utopian fantasies and state firmly instead that art which is sold at prices that are affordable to most – that is social art. In this regard, illustrated books deserve a prominent position. Through public libraries and bookshops such books conveys fine art to a wide audience, admirably resolving a question of education for the people.”49

Unlike Wilmann, Swane and Zahle made no particular note of the depiction of the city or of the working-class neighbourhood and its inhabitants as a distinctive trait of John C. Rather, the qualities emphasised by Erik Zahle were his artistic charm and idiosyncratic, curly hand that gradually homed in on its subject. He also pointed to John C.’s originality – his ability to create vibrant, poetic works based on subject matter that had hitherto never been utilised in art and which was in itself without great significance. After John C.’s death Leo Swane described him in these terms:

“As an artist, John Christensen was entirely autodidact, demonstrating true originality in his works. In the streets of Nørrebro and the Assistens churchyard he found subject matter from our present-day Copenhagen that none have mined like him. He captured such scenes with a rarely seen keenness of observation of the milieu, and he was able to take even insignificant motifs as the starting point for vibrant and frequently highly poetic works. […] As one followed his evolution there could be no doubt that this was an artist of genuine importance, forging his own way ahead. Thus, he won a name for himself, both among fellow artists and among a more general art audience.”50

These words of praise were uttered in an application submitted to a foundation; Leo Swane phrased this application on behalf of a circle of artists and other friends seeking to secure some help for Dagny, who was suffering from depression after the death of John C. Those efforts coincided with the memorial exhibition staged by Kunstforeningen, which opened on 3 February 1940, just a month after the artist’s death; an exhibition that saw Zahle expending great and focused efforts on the preparations. [fig.10]

A trusted friend

During the tightly-scheduled preparations for the memorial exhibition Zahle was assisted by Poul Uttenreitter. Absolutely no instances of the moniker ‘the Barber Painter’ appear in the correspondence between the two. The artist is referred to as ‘John Christensen’, in Poul Uttenreitter’s case simply ‘John’.51 This corroborates the testimonials indicating that out of all the critics of the time, Uttenreitter had the closest personal relationship with John C.; indeed, he became one of his close friends. Erik Zahle called him “John Christensen’s friend and confidante”,52 Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg stated that John C. “got a very good and loyal friend in Poul Uttenreitter, whom he adored”,53 and finally the painter Emilie Demant Hatt wrote a letter to her husband when John C. was on his deathbed, stating that Dagny and John C. “count the Uttenreitters and us as their true friends.”54

Poul Uttenreitter’s impact as an opinion former on the Danish interwar art scene is perhaps not sufficiently recognised today. He had known Leo Swane since childhood,55 and they shared a great degree of affinity and complicity with the first generation of the Grønningen group – as well as their predilection for John C.’s work, of course. When John C. needed his first-ever catalogue foreword in 1935 – in connection with an extensive solo show at Arnbaks Kunsthandel – Uttenreitter picked up the pen. Here he did not elaborate on the narrative that viewed the artist and his work through the lens of the specific barbershop setting; rather, he effected a break with the tradition established by Houmark by opting for a bird’s eye perspective when describing the artist’s world. To Uttenreitter, John C. was a Copenhagener par excellence:

“To those who are enemies of paintings of home and hearth, it cannot be denied that this world is confined by a circle that touches upon the Dronning Louise bridge and has its centre somewhere near the Assistens churchyard. It never occurred to him to paint subjects outside of this circle. His spring is a spring that takes place between walls, his evenings in the garrets of Fyensgade are awash with the light of the heavens vaulting above a forest of chimneys, and in summer his holidays from paved streets are set in the Lilliputian world of allotments on the far side of the circle.”56

The comments regarding home and hearth were a jab at the Danish architect, writer and critic PH, who – in essays from 1932 and in his book Hvad med kulturen (What about culture) from 1933 – had issued warnings against the reactionary aspects of celebrating one’s immediate surroundings – without, however, including John C. as part of this reviled tendency.

Poul Uttenreitter eventually came to own no less than 15 works by John C., including the watercolour In the Garden from 1937, which is now part of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art.57 After the artist’s death he also involved himself actively in alleviating Dagny’s dire economic straits. He strove to have the SMK buy a painting from her or from a private collector – in either case the objective would be for Dagny to have the money. The collector Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg was reportedly very favourably disposed to this latter proposal,58 but the attempts to persuade the Gallery Commission were unsuccessful. An entry in the acquisitions committee’s protocol dated 10 February 1940 states that the committee had visited “John Christensen’s memorial exhibition at Kunstforeningen, where there was no general wish to make any purchase from the paintings on display. Swane informed us that the Royal Collection of Graphic Art already owned a substantial number of drawings and watercolours by the artist, and there was general consensus that he is presumably best represented at the museum in this capacity.”59

A fortnight later the museum received one of the paintings featured at the memorial exhibition, Snow-Clearing from 1933, as a donation from Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg. The offer of this gift was arranged by Uttenreitter as a go-between, and Leo Swane accepted the painting as “one of the few that could properly represent him here.”60 [fig.11]

Certain differences can be seen between what Poul Uttenreitter emphasised in John C. compared to the traits accentuated by Swane and Zahle. Uttenreitter pointed to the primitive and sensitive aspects, but also to his drastic and humorous qualities; an assessment that he would elaborate on in his small book on John C. from 1940.61 He drew particular attention to the circus scenes and Nørrebro motifs, praising them for their entirely original, empathetic observation of the fantastic life that unfolded there. Like Leo Swane, Poul Uttenreitter also pointed out that John C. was not a ‘social artist’ in the traditional sense of the term. Yet he also emphasised how the artist identified intimately with the proletarian Nørrebro area and all its people, rallies, protest marches and red flags waving. Uttenreitter prized such solidarity with the working-class neighbourhood, its inhabitants, culture and traditions. However, like Zahle and Swane he too felt a need to deny the existence of any deliberately social/political content; such intentions were anathema in the worldview favoured by these three friends – whereas Wilmann took a different view.

The primitive and the democratic

In his book about the history of the SMK, Villads Villadsen has described Leo Swane’s devotion to contemporary art as being firmly restricted to a narrow circle of Swane’s contemporaries, specifically the circle around Giersing and Grønningen. Swane’s acquisitions of contemporary art after 1930 are portrayed as tasks he completed without any real interest, exclusively out of a sense of obligation – except when buying works created by the aforementioned circle. For example, the book states that: “due to his notorious resentment of all abstract art, the obligation to regularly add new contemporary art to the collection meant that even more of the least interesting art produced at the time was bought.”62

Leo Swane has called such assessments down upon his own head due to his infamous dismissal of Picasso; a response that posterity has, quite naturally, viewed as an example of a vision so blinkered it verges on the disqualifying. Swane’s position has grown increasingly incomprehensible as the narrative about 20th century art has become a narrative about modernism’s steady evolution via new breaks and new departures;63 a position that has largely consigned all those trends and artists that Swane favoured to obscurity. They quite simply did not appear interesting to art history any more. However, this in no way means that they were not the object of Swane’s genuine interest and commitment. For example, he evinced an enduring interest in artists with a robust, ‘primitive’ approach to things; this included the Swedish artist and sculptor Bror Hjorth’s rough, colourful art with its obvious links to folk art motifs and modes of expression.64 He shared this interest with Erik Zahle, who knew and appreciated Bror Hjorth – as did Poul Uttenreitter,65 whose predilection for all things primitive and primordial was also evident in connection with the Sami writer and artist Johan Turi; Uttenreitter collaborated with the painter Emilie Demant Hatt to have Turi featured at the KE in 1928.66

The period’s widespread appreciation of the primitive and primordial had an impact on the reception of John C., but so too did the strong focus on the social aspects of art and its democratisation. As has already been touched upon, John C.’s career ran its course while discussions on worker’s art and social art were a recurring feature of cultural life. However, the discussion on what ‘proper’ working-class art should be like is not the most relevant point when considering the reception of John C. It was a discussion dominated by firmly established, opposing fronts set down by groups of social democrats, the so-called cultural radicals, and the far left; the debate mainly centred on the link between aesthetics and politics, particularly on the progressive potential of aesthetic innovation. John C. was neither a participant nor a subject in this discussion. In his case a far more wide-ranging interest in democratisation of the realm of culture is a relevant context for the appreciation of his art.

Expanding the traditional art audience to also include the working class was a strongly held wish among artists and art professionals alike, which makes the issue relevant when considering John C. as an artist. In the 1930s there was widespread support for the view that a democratisation of cultural life – in the sense of having cultural assets made accessible – should be ensured through efforts on the part of artists, institutions and movements alike. The arrival of working class people and the workers’ movement in the field of culture, both as opinion formers and as potential art audiences and consumers, was accompanied by a range of specific initiatives intended to forge stronger links between the common people and ‘good art’. Several of the new artist groups that emerged in the 1930s deliberately set out to send new messages to mass audiences via their exhibitions. The Corner and Koloristerne groups, both of which were established in 1932, and Kammeraterne, who first exhibited in 1935, all offered installment plans for prospective buyers and emphasised the fact that people with modest incomes were now also able to buy art. Broadsheet newspaper Politiken wrote the following about Koloristerne, of which John C. was a founding member: “Audiences should visit them in order to view art – and to buy art at very affordable prices, too, as the artists themselves expressly state. For they believe that that the ‘social’ aspect of art resides in reaching a wide audience, not in the art itself, which is elevated above such matters.”67

The fact that some of the artists, as well as the representatives of the established art institution, all felt that it was incumbent on them to denounce a specific concept of ‘social art’ – emphasising that their take on social art focused on art that was accessible to all rather than art intended as political agitation – rests mainly on a reluctance against being harnessed to a particular political position; one that was most forcefully expressed by the radical left-wing Monde group. The repeated avowals that John C. did not create ‘social art’ were not intended to suggest an absence of commitment to social issues or situations in his art. Most observers presumably clearly perceived his affinity and solidarity with the neighbourhood in which he lived. Rather, the fact that he was indeed received as a social artist – but in a good way – reflects how this theme was so strongly embedded in the era that it coloured many assessments, and artists of John C.’s type would inevitably be viewed through that lens.

The collectors

Given that the objective of selling good art to a wide audience was often openly proclaimed – for example in the introductory leaflet published by Arbejdernes Kunstforening (The Worker’s Art Association) in 1936, which promised potential members that they would regularly receive “offers of fine art of good quality, to adorn your home and delight your eye – at affordable prices” – it may be worthwhile to examine who actually bought John C.’s art when his sales increased. Even though the question is not easily answered, given that so little material from the artist’s own archives survives today,68 it is nevertheless possible to answer the question of whether the class-related barriers of education were in fact broken down. The answer is no. Certainly if you look at the patrons and buyers that had a real impact on John C.’s finances.

In the early 1930s his prices were so low that any profits made from art were of little or no consequence compared to his earnings as a barber. From the mid-1930s his prices went up, yet his art remained affordable to most; it was not the exclusive province of the rich. Indeed, most buyers did not belong among the very affluent; rather, they were mainly educated middle-class citizens and, to some extent, art critics and fellow artists.

In an interview with Ekstrabladet in 1935, John C. related how he sold his first painting in November 1934 when a university professor entered his barbershop, put down 200 kroner on the desk and carried the painting off with him. John C. almost had a stroke from the surprise of making such a straightforward sale – in cash, even.69 There is much to suggest that this buyer was Gudmund Hatt, a cultural geographer who was married to the painter Emilie Demant Hatt; he may have been the first patron to ever buy directly from the barbershop and at the ‘regular’ price, which at this point, in the mid-1930s, came to around 200 kroner for a medium-sized John C. oil painting. At the time of the artist’s death the Hatts owned at least ten works by John C., of which five were oils.70 No mention is made to suggest which of these paintings was Hatt’s first purchase, but it may have been Sunshine Girl from 1934, which O.V. Borch would later describe as “… the Sunshine Girl on her bicycle, executed in Chagall’s transparent style, with the growing Tree of Life”.71 The couple also owned Self-Portrait from 1934, but that painting almost seems too small to have cost the price stated.72

Emilie Demant Hatt was the official owner of most of the couple’s art collection. She began her career as a naturalistic painter, but in the interwar years she developed a visionary vein of Expressionism. Today she is perhaps chiefly remembered for her efforts to raise awareness of Sami life and literature – e.g. through her collaboration with Johan Turi, whom she encouraged to write; she helped him publish Muitalus sámiid birra, 1910 (En Bog om Lappernes Liv) (A Book on Sami Life). We do not know how the Hatts and John C. first became acquainted, but they gradually became friends, and John C. drew and painted several portraits of Gudmund that do not seem to have been commissioned by the sitter. Indeed, the largest and most subtly humorous of these, Wise Man in a Spring Garden, remained in the artist’s ownership (it is now owned by the Museum of Copenhagen). Shortly before John C.’s death the couple offered to buy yet another painting for their collection in order to help the family, which was facing financial problems.73 The work in question was presumably Circus Artists in the Ring from 1932.74

The one patron who had the greatest financial impact on John C. was undoubtedly Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg, who would later become a major collector of abstract art, and whose first passion in the field of collecting was oriental crafts and design. At this point in time her collection interests had shifted towards Danish Modernism, with Olaf Rude, Edvard Weie, Harald Giersing and Jens Søndergaard as key figures, and these were gradually supplemented by artists from the new groups emerging in the 1930s. Koloristerne were prominently featured in the collection, and John C. came to have a unique position. Fonnesbech-Sandberg built a diverse and representative collection of more than 100 works by John C.; a collection that has since become scattered to the four winds: she was obliged to sell her collection when her husband’s business – Torben Fonnesbech-Sandberg was a tea merchant – suffered during World War II.75

Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg paid standard prices for most of her collection, ranging from 15 kroner for a small drawing up to 200 or 300 kroner for a painting. Her affluence was not such that she eschewed instalment plans; she would typically pay John C. 50 kroner every two weeks so that he gradually got a relatively steady income from her.76 We do not know exactly when she made her first purchase, but it probably took place at one of Koloristerne’s exhibitions in the mid-1930s.77 There is much to suggest that she knew John C. personally; she visited him in his Nørrebro and Vridsløsemagle homes, sat for portraits on several occasions, and devoted a substantial section to him when writing her memoirs.78

After John C.’s death Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg helped and supported his family and also helped maintain the general awareness and appreciation of his work. Poul Uttenreitter strongly believed that she paid for his funeral.79 What we know for certain is that she launched the collection to fund a memorial headstone for John C. in 1946; the stone was officially unveiled at Assistens churchyard on the 50th anniversary of the day of the artist’s birth. The memorial stone was designed by Henry Heerup, another artist that she treasured particularly highly.

John C. held a special position in her collection; a claim that is substantiated by the fact that she kept most of the works when she was first forced to sell parts of her collection for financial reasons in 1940; she hung on to them until 1943. To Fonnesbech-Sandberg, John C. became a gateway to the abstract artists she would later collect. Perhaps John C.’s art also helped open her eyes to the art of Henry Heerup, who was the only artist of the later CoBrA association to be part of her collection in the 1930s. What we do know with greater certainly is that her collection of John C.’s art was responsible for first establishing a direct acquaintance between herself and the abstracts. Asger Jorn, whose connection to Fonnesbech-Sandberg would prove especially productive, first visited her home on an errand to pick up two John C. paintings for reproduction in the journal Helhesten.80 In the journal, the pictures were accompanied by a text by Robert Dahlmann Olsen that positioned John C. as “the link between the younger and older generations that has hitherto been missing in Danish art”. Dahlmann Olsen preferred his early paintings. Little Girl Looking at the Stars, 1931 and Autumn Evening 1933 were the examples selected. Whether they were chosen by Dahlmann Olsen or Jorn we do not know, but the praise heaped on John C. in Helhesten focused on the spontaneous and symbolic aspects of his work:

“His first symbolic imagery constitutes a spontaneous painterly breakthrough. It embodies a pent-up store of imagination and emotion that refused to be fettered by commonly accepted aesthetic ideals, and which could only run its natural course by bursting the seams of naturalistic form and proportion, surrendering entirely to the fantastical and the mystic. His symbols are imbued with a magical, painterly strength and forcefulness of the kind that arises around the primitive symbolism of our culture.”81

Such emphasis on spontaneous, mystic and magical qualities was entirely novel in the reception of John C. at the time, but is certainly in keeping with the spontaneous-abstract project that characterised a significant part of the circle around the Helhesten journal. One might reasonably assume that the curly, doodling qualities of John C.’s hand and the sense of unpredictable compositional processes that permeates many of his drawings also spoke directly to the Helhesten circle. So too would his open, all-embracing relationship with any mode of expression that happened to be at hand, regardless of whether it belonged to the realms of high art or was anchored in popular culture.

The ranks of early collectors of John C.’s work includes a few other women, among them Betty Crone, who was married to the director of the Danmark insurance company, Frederik Lønborg Crone; at the time of John C.’s death she owned at least sixteen works by him.82 A ‘Th. Crone’, whom the memorial exhibition inventory lists as owning a painting, is presumably the couple’s eldest son Thomas. Betty Crone continued to expand her collection until hear death in 1948, and the Crone family – which has many branches – is a prominent example among the several families that have maintained their John C. inheritance and even continued to expand that collection. We do not know whether Betty Crone made purchases directly from the barbershop. Three of the works were purchased from Arnbaks Kunsthandel, while others were acquired at the Koloristerne exhibitions and paid for in monthly instalments over the course of 1938–39; the instalments were fairly regular and mostly set at 20 kroner, whereas Th. Crone would pay rates of as little as 5 kroner every month.83

The home of the parents of graphic artist Povl Christensen attracted many artists, and quite a lot of art was purchased for their Kochsvej residence. It was not Povl Christensen’s father, the merchant H.C. Christensen, who was interested in art, but his mother Petrea, who reportedly also bought works directly from the barbershop.84 Her collection of John C.’s art has largely been kept in the family, but Self-Portrait from 1936 was donated to Randers Kunstmuseum by Povl Christensen, who stated that his mother owned seven paintings and fifteen graphic works by the artist. [fig.12]

As we have seen, several of the early collectors were women who bought art with whatever money they could keep for themselves out of housekeeping budgets that may have been fairly substantial for the time, but not lavish. There were, however, male collectors too. Their ranks included Jørgen Nørballe, who owned at least 39 works, some of which were early drawings and watercolours that have since ended up at The Workers’ Museum, Copenhagen.85 He was an upper-secondary schoolteacher at Nørre Gymnasium, which was then located at Gartnergade 15, and he would have frequented the Kapelvej neighbourhood during the course of his everyday pursuits. It is likely that he had his hair cut at John C.’s barbershop; they certainly became friendly enough to exchange Christmas cards and other greetings.86

Men, too, would buy works of art on an instalment plan; for example, the senior bank clerk P.E. de Renouard paid by degrees,87 and so did Jarl Borgen, who would later go on to become a successful publisher; he made his first purchases directly from the barbershop and eventually came to know John C. well enough to get invited to both his homes, in Nørrebro and in Vridsløsemagle.88

The collectors who bought art during John C.’s own lifetime also included a range of art historians and critics. Poul Uttenreitter has already been mentioned. He owned at least fifteen works, including Rain and Storm, 1936, which is now owned by ARoS Aarhus Art Museum. Erik Zahle owned at least three works, two of which were bought from Arnbak, while Jan Zibrandtsen owned one. A wide range of artists also had John C.’s art in their homes; some of those works would have been bought outright, others swapped or received as a gift. This group of owners included the sculptors Gottfred Eickhoff, Eigil Knuth, Knud Nellemose, Hans Olsen and Adam Fischer, the painters William Scharff and Aage Gitz-Johansen, the draughtsman Børge Biilmann Petersen and quite a few more. Finally, it is worth noting that the Swedish painter and sculptor Bror Hjorth – whose own work saw him working with his materials in a coarse, ‘primitive’ manner, drawing heavily on the forms and symbolism of folk art – bought two pictures from Arnbak in 1938.89 We do not know whether Bror Hjorth met John C. during his stays in Copenhagen. He may also have become aware of his work through Swane, Zahle or Uttenreitter, with whom he was regularly in touch.

Holger Hansen, a mechanic, is the only worker listed as the owner of a John C. work in the inventories prepared by Erik Zahle on the occasion of the memorial exhibition. Zahle has noted that Wilmann may be able to come up with the names of other such owners. However, we should probably apply some reservations regarding the size and scope of Zahle’s and Uttenreitter’s acquaintanceships among working men, and hence we should also be wary when considering their actual opportunities for possessing full insight into John C.’s patronage from workers. For example, many such buyers may have purchased their works directly from the barbershop. But it seems reasonable to assume that they would have been aware of any major working-class collectors if they had existed.

Decline in institutional interest

The years that followed after John C.’s death brought a series of memorial exhibitions that reaffirmed his broad appeal and acclaim. As has already been mentioned, the first such exhibition took place at Kunstforeningen just a month after his death, the next was staged at the Fischer og Krarups Kunsthandel in September that year, and in 1946 Foreningen for ung dansk Kunst (The Society for Young Danish Art) arranged an exhibition at Tokanten on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the artist’s birth. The latter became a veritable hit; it was visited by 3,000 people in its first week and was regularly supplemented by works that emerged from private collectors.90

Even though the artist continued to be known as John Christensen or simply John C., the ‘barber’ aspect was a very prominent part of his identity. Fellow artist Folmer Bendtsen even found it difficult to think of the artist without mentally adding ‘the Barber’, and even more difficult to not associate him with the Nørrebro neighbourhood – “that quirky Nørrebro atmosphere that was his unique contribution to this decade of Danish art.”91 The distinctive atmosphere of the barbershop was also a regularly revisited topic – and one that was frequently embellished upon. Nørrebro – this densely populated suburb of Copenhagen, a provincial city right in the heart of the city, with a gallery of glorious characters – was a firmly established part of the various descriptions of John C.’s distinctive traits as an artist, such as his immersion in detail that led to a barefaced vein of realism, but also to a special sense of poetry. Descriptions would then typically go on to focus on how he combined the autodidact and unspoilt with something innately artistic, on the merging of naivety and sophisticated subtlety. A new trend emerges in these descriptions: emphasis is placed on positing the artist within the grand narratives of art history, on positioning him within the upper echelons of art, preferably amongst the great French artists. Preben Wilmann believed that John C. possessed “a vibrant, reverberating artistic sensibility that is more frequently found in France than in Scandinavia”,92 Kai Flor summed up his work by stating that he was “on a par with the great French draughtsmen”,93 Kaj Borchsenius was reminded of le Douanier Rousseau,94 whereas Else Kai Sass, who would later become professor in art history, called him “A Danish van Gogh”.95

Another characteristic feature emerging in the assessment of John C.’s art at this point is a renewed focus on how death was an ever-present reality throughout his life and work. After his early death, his life came to be regarded as having been forever lived in the shadow of death, for example in the aforementioned article by Folmer Bendtsen and also by Kai Flor, who wrote about his “defiant living” and believed that “The wall between Life and Death unleashed the truest and most deeply personal aspects of his mind”.96

After the rapid succession of memorial exhibitions things did, however, go somewhat downhill for John C., particularly as far as the interest shown by art institutions was concerned; he was even left out of the reference works for several decades. Nevertheless, during that same period the artist was reinterpreted in the context of the labour movement, primarily due to the efforts made by Alma and Vagn Nielsen, a married couple who, on quite ordinary workers’ income, built an extensive art collection from 1940 onwards, focusing mainly on works by John C., Hjalmar Kragh Pedersen and Henry Heerup. Their collecting was permeated by a strong commitment to improving and strengthening the relationship between workers and contemporary art; for Vagn Nielsen this endeavour focused on John C. in particular.97

Vagn Nielsen first grew interested in art in 1939–40 when he attended a series of museum lectures for the unemployed; upon getting back in employment he made his first purchases of art.98 Those purchases were made at Fischer and Krarup’s memorial exhibition in September 1940, where he bought the ink drawing The Artist and his Models from 1930 and the etching The Entrance of the Assistens Churchyard from 1938.99 His John C. collection eventually numbered sixty works, seven of which were paintings; most were small-scale works except for the large Self-Portrait with Figure from 1931. Several of the works were bought from the artist’s widow, with whom he established a relationship of mutual trust.100 [fig.13]

Vagn Nielsen would have liked to have known John C. personally and did everything he could to mitigate his sense of loss over this fact. He visited art dealers such as Henning Larsen, he collected photographs and printed material for an ever-growing ‘John C. archive’, he contacted Max Müller and Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg to obtain more information about some of the works in his own collection that had previously belonged to them, and overall he gathered and secured information and documentation that offers a highly valuable and significant supplement to the meagre store of information that would otherwise have been obtainable today. For this he deserves great praise.

Alma and Vagn Nielsen gradually became publicly known as ‘collectors without deep pockets’, and Vagn wrote about his collecting activities on numerous occasions, seeking to prompt other workers to assign greater priority to acquiring art for their own homes. For him, art represented a counterpart to allotment gardens; they had a similar human and poetic dimension:

“it is nice to also have an allotment indoors, and I do, the most delightful allotment imaginable. It is always ready to welcome me with the songs of nightingales, flutes and brass bands alike. The pictures on my walls are my allotment garden. The pictures are windows opening up on lovely, lush gardens and doors leading straight into the hearts of others. Such walls are certainly something to be desired.”101

Vagn Nielsen regarded the assessments made by art experts about the aesthetic and fiscal value of art as being entirely without interest to “everyday people”. The couple’s collection centred on John C., Kragh Pedersen and Henry Heerup because those artists “let Man take centre stage. This is not to say that there are always people in their pictures, but they paint Man and the things that matter to us as human beings.”102

Vagn Nielsen’s view of the relationship between art and workers had a certain kinship with the views that prompted the establishment of Arbejdernes Kunstforening (The Worker’s Art Association) in 1936: a firm belief that it was crucially important, in order to lead a good life, that workers should struggle to acquire a share in the values that good art has to offer, just like they had fought to acquire a larger share of the economic values in society.103 Even though the general developments in the labour movement’s cultural politics brought some disappointments in their wake, and even though he presumably did not persuade many workers to collect art with the same enthusiasm that he did, Vagn Nielsen never abandoned his personal cultural project. He happily made his works and archives available for exhibitions, and a bequest in his will ensured that the couple’s entire John C. collection, complete with all documentation, would be donated to a museum once they were both dead.104 [fig.14]

The main body of Vagn Nielsen’s collecting efforts took place in the 1950s and 1960s, and the decades that followed have not yielded any significant new insights. The few John C. exhibitions held in later years have all accentuated the site-specific, local context of his oeuvre. This was true of “Barbermaleren” John Christensens arbejder især fra Nørrebro (Works by John Christensen, ‘The Barber Painter’, especially from Nørrebro), shown at the Museum of Copenhagen in 1976, and of Barbermaleren John Christensen at Formidlingscenter Assistens in 2000. By virtue of its location alone – the cultural centre at the Assistens Churchyard – the latter of these two exhibitions accentuated the specific location where the artist’s work was done. The approach was also evident in the catalogue, which conjured up 1930s Nørrebro in an atmospheric manner; the artist and his work served as the basis for an exercise in folkloristic local history writing.105 In terms of exhibitions, then, John C. has been relegated to the realm of cultural history, which should in no way be regarded as a disparaging assessment. The architect Henning Nicolaisen and Formidlingscenter Assistens went to very great efforts to track down works for a representative exhibition in 2000, but the general interest from art institutions has declined greatly over the years.

A historiographic comment

In the 1930s John C. was featured in reference literature as an artist who pointed ahead in time. Leo Swane’s perception of his art has already been accounted for, and Niels Th. Mortensen’s Dansk Billedkunst gennem en Menneskealder (Danish Art of the last Generation) from 1939 included John C., who was praised for his innovative and imaginative work as a draughtsman. Mortensen’s overall assessment of the period was that the advent of Expressionism had liberated art from all dogma, introducing complete freedom of expression and paving the way for “a range of gifted, uninhibited, unpretentious painters who seemed to step straight from the barbershop or the classroom into the holiest of holies in the realm of art.”106 Mortensen had a keen eye for the new complexity and diversity that arose on the Danish art scene of the 1930s, and his approach was infused by a kind of pluralism that can still be discerned in Jan Zibrandtsen’s reference work Moderne dansk Maleri (Modern Danish Painting) from 1948, which takes the form of a series of biographies and very scanty general summaries. In this book John C. is favourably described as one of the very few true Naïvists in Danish art.107

After this, John C. had to take a leave of absence from reference books for quite a while. As has been pointed out by the Swedish art historian Hans Hayden, Modernism attained its real impact as an aesthetic and historiographic paradigm during the first decade after World War II. It is true that some avant-garde movements had entered the art institutions in the 1930s, usually now under the term ‘Modernism’, but it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that Modernism and modern art were emphatically considered one and the same thing; with this move, the evolutionist Modernist narrative focusing on stylistic innovation assumed its dominant position.108 This narrative was instrumental in bringing about the marginalisation of great sections of the art scene as largely uninteresting to art history, and it has had long-term negative repercussions for interwar art, which had been quite widely bought by art museums at the time, but not yet been made the subject of much research.

The artist and art historian Jens Jørgen Thorsen’s 1965 book Modernisme i dansk kunst, specielt efter 1940 (Modernism in Danish Art, particularly after 1940) provided the first major art historical account of the Modernist/avant-garde movement in Danish art from its earliest beginnings to the present day. It related the story of how Danish Modernism had its wellspring in Vilhelm Lundstrøm’s ‘crate pictures’ from 1917–19, of how it was continued by the Surrealists associated with the linien group and then unfolded to its full extent by the Spontaneous-Abstract artists associated with Helhesten and CoBrA. Thorsen reproduced and reinforced the avant-garde groups’ own narratives: the linien circle had explained its endeavours as a continuation of Lundstrøm’s Cubism infused with new psychological aspects, and the artists around Helhesten had also pointed back to Lundstrøm as the founding father of their movement; the only difference being that they interpreted his crate pictures as Dadaist and spontaneous.109

For decades, Danish art history writing regarded the emergence of linien in 1934, drawing on ideas from Bauhaus and international Surrealism, as an endeavour that finally picked up the mantle after Vilhelm Lundstrøm’s montage works, arriving on the scene after almost fifteen years of wandering in the wilderness during which artists had turned their back on the wider art scenes abroad. The period between World War I and the mid-1930s was regarded as a temporary phase characterised by an embarrassing lack of innovation, especially by a complete absence of efforts to follow up on the initiatives that had taken place around the journal Klingen (The Blade). This position found forceful expression in the 1970s, for example in Troels Andersen’s contribution to Hus – billede – dekoration, 20’erne i Danmark (House – picture – decoration, the 1920s in Denmark) from 1976:110 he regarded Danish art from the 1920s as problematic because the artists failed to retain an international outlook. Knud Voss’s contribution to Dansk kunsthistorie (Danish Art History) (vol. 5, 1975) is also permeated by the concept of a modernist evolution in art; for example, he regards the absence of Dada in Danish art as a problem that may potentially have long-term ramifications – it is regarded as a natural evolutionary stage that Danish art has neglected to live through. Whereas the reference works from the first half of the century describe the interwar art scene as heterogeneous and characterised by a pluralistic co-existence of different movements, a shift had occurred, assigning the highest position in art’s hierarchy to a ‘revolutionary spirit’, i.e. avant-garde antagonism; at the same time a corresponding loss in status occurred for all experiments aimed at giving voice to the human condition in modern urban living or at forging closer links between art and a wider audience – both of which were key concerns for many young artists of the interwar years. Within the narrative that posits modern art as something that is driven by an inherent logic of constant, natural evolution, many of the artists who had been much acclaimed and highly visible during the interwar years quite simply no longer seemed relevant to art history.

However, in the 1990s John C. got a second chance, this time recast as a footnote within what was supposedly a vibrant, flourishing traditionalistic movement on the Danish interwar art scene. In Ny dansk kunsthistorie (New Danish Art History) (vol. 7, 1995) Villads Villadsen and Henning Jørgensen established a new narrative that falls into two separate parts: tradition and Surrealism. This can be said to effect a break with the hegemony of the one-sided narrative of the evolution of art, but it still did not treat avant-garde art and so-called traditional art from the interwar years as part of the same overall history.111 John C. makes an appearance in the section on “Tradition”, where he is placed in the very margin of things, being mentioned in the same breath as Madsen Ohlsen in the chapter on ‘the Corner tradition’, specifically under the thematic heading “Hjemstavn” (Homeland) – i.e. associated with depictions of home and hearth.112 Mikael Wivel devotes a little more space to John C. in his Dansk kunst i det 20. århundrede (Danish Art in the 20113 Century) from 2008. Wivel too wished to counteract the privileged position that had long been attributed to Modernism, seeking for new avenues of approach that might upgrade tradition. In this context John C. was placed within the capacious category “De utilpassede” – literally ‘The Misfits’ or ‘The Maladjusted’ – alongside a number of other artists who had been marginalised by art history.

However, neither of these categories – traditionalist or misfit – seems useful as the starting point for a meaningful reinstatement of John C. in art history; he was not at all maladjusted, but very well integrated in the art scene of his day, where many saw him as representing something for which the era had a particular and distinctive need. Focusing on this latter position would make it possible to use him for an examination of values and broader tendencies that were recognised at the time, but have later been rendered invisible by art history. If John C. is to be brought to light from the art museums’ storage facilities and be meaningfully presented in displays and exhibitions, we must abandon the evolutionist narrative about modernism as well as the polarising presentation of avant-garde versus tradition in favour of a narrative about an art scene that grew increasingly complex in the 1930s – complex in terms of artist groupings, the channels available for the presentation and dissemination of art, potential art buyers, and cultural agendas. The examination of key values found in the reception of John C. in his own day and immediately afterwards points to a context where the artist is associated with a vein of institutionally approved ‘primitivism’ that celebrated the uninhibited, the immediate and the naïve, but which was quite far removed from the keen interest in ‘primitive’ peoples and tribes that dominate the main narrative about Primitivism in the 20114 century. We have also seen that an extra layer was added to the general appreciation of the primitive and autodidact aspects of John C.’s work: the concept of the artist producing and distributing his art as ‘one of the people’; an approach that linked him to the era’s keen interest in a democratisation of culture in general and the growing awareness of the labour movement and the working class as important new factors within the field of culture. [fig.15]

Of course, reassessing and reinstating John C. as relevant today cannot be done by simply reproducing the reception seen in his own day. However, the pluralistic approach of that reception can pave the way for other ways of framing art history’s overall picture of the period, prompting and inspiring art historians to think beyond and across the established distinctions between tradition and the avant-garde. When taking such an approach, it would be natural to use John C. as a springboard for further examining a trend that is urban in its general approach, interested in issues concerning popular appeal and a democratisation of culture, and all-embracing and uninhibited in terms of artistic modes of expression, unfettered by convention and theory. It is, of course, quite natural to consider John C. in relation to other early members of Koloristerne, especially to Hjalmar Kragh-Pedersen, who is now entirely forgotten, but who was widely acclaimed in the interwar years for his Futurist-Expressionist images of the modern human condition in the iron grip of industrialism. However, equally obvious candidates include Søren Hjorth Nielsen from Decembristerne, who also focused on city life during the interwar period, particularly on the toilworn, down-at-heel characters one could find in working-class neighbourhoods, and Jens Søndergaard from Grønningen, whose images of urban life share many traits with John C.’s works in terms of their angle of approach and figures. One might also include Storm P., a unique and solitary figure on the Danish art scene whose art spanned and embraced the childlike, the morbid and the satirical, and who also leaned towards a certain coarseness and quirkiness in his choice of artistic devices. What is more, it would seem quite obvious to establish a kinship with the artist Henry Heerup; as a young man he lived in the Nørrebro area quite close to John C.’s barbershop, and he too became the subject of notions about immediacy, accessibility and popular appeal. The fact that Heerup’s works from the interwar years are now usually presented as part of an entirely different narrative, primarily the history and pre-history of CoBrA, is a direct result of the narrative of Modernism and its penchant for categorising artists in accordance with their affiliations with internationally prominent groups. The fact that Heerup contributed to linien and later to CoBrA has proven decisive for his position in art history, but when he made a guest appearance with Koloristerne in 1940 this matter has not yet been decided, and at the time he was perceived as having been invited to mitigate the sudden loss of John C.