Summary

Jeannette Ehlers grapples with the history of Denmark’s involvement in colonialism and slavery, and their afterlife in the present. Until recently, this violent chapter of national history has received only scant attention in Danish public discourses. This article seeks to tease out how Ehlers renegotiates the self-perception and history of a country challenged to learn how to live with cultural diversity, by examining Ehlers’s performance Whip It Good (2013‒ ) and I Am Queen Mary (2017), a public sculpture commemorating the resistance to Danish colonial rule, co-created by Ehlers and La Vaughn Belle.

Articles

In her essay “Being the Subject of Art”, the feminist author and activist bell hooks reflects on what it entails to be positioned as the subject of art.1 hooks sees the body as “the first site of limitation” and suggests that individual and collective change is dependent on bodily transgression and the violation of various kinds of boundaries: “To transgress I must move past boundaries, I must push against to go forward. Nothing changes in the world if no one is willing to make this movement.”2

The words of bell hooks could have been the motto of Copenhagen-based artist Jeannette Ehlers. Ehlers is an heir to a proud tradition established by artists of colour from the 1970s onwards: the practice of accentuating the racialised body to use it as a medium of critique of racism against Black people – a type of racism with deep roots in Western colonialism. Like some of her predecessors, Ehlers has drawn on performance art and performative imagery to spotlight how the effects of racialisation manifest themselves as embodied experience. The term “performance art” denotes art that deploys the body as an object to subvert cultural norms and explore social issues, as well as blurring the boundaries between the artwork perceived as object and performance perceived as action.3 In many cases, artists have used their own bodies, thereby fashioning themselves as both the agential subject and the object of art. Where Black artists are concerned, this double engagement of the artist’s body and subjectivity often points to the bigger question of the place of the racialised body in Western history and society, and by implication its place in art history. The works by Ehlers discussed in this article are a case in point. Visual identification is always negotiated between subjects and objects, or rather “between and within viewing and viewed subjects”.4 As the African American and gender studies scholar Uri McMillan has argued in his study of Black women performers, “performing objecthood” can be a powerful tool for recasting how Black female bodies are perceived by others: “[P]erforming objecthood becomes an adroit method of circumventing prescribed limitations on Black women in the public sphere while staging art and alterity in unforeseen places.”5

What follows is an examination of how Ehlers seeks to circumvent such limitations in the public sphere, which is understood here as an encompassing sphere that includes public urban spaces and museums as public venues, generators of public debate and gatekeepers of the boundaries of culture and heritage. Firstly, I will turn briefly to the recent history of performance art. I use the example of American artist Adrian Piper as an entry point to underscore that although the problematics Ehlers explores are historically rooted in Danish colonialism, the issues she addresses are transnational; and more specifically that, although Ehlers is based in Denmark, her works are connected to the artistic traditions of the African diaspora.6 As the African American studies scholars Celeste-Marie Bernier and Hannah Durkin have noted, African diasporic artists often deploy “radical and revisionist practices by which to confront the difficult aesthetic, no less than the political, realities surrounding the social and cultural legacies of the African diaspora”. Such revisionist practices do not fit seamlessly into the category of “national” traditions, although I would argue that, in Ehlers’s case, they are part of a national culture, too. The blurring of formal and thematic boundaries in Ehlers’s works testify to the fact that her take on “national” issues is shaped by the processes of cross-cultural exchange and patterns of intertextuality developed within centuries-long African diasporic art histories.7 From Piper, I move on to Ehlers, the selected works and the theoretical framework undergirding the ensuing analysis of how she has used embodied transgression of boundaries and normative Western images of the body as an emancipatory means to rewrite the dominant narrative of Danish history and create a space for racialised subjects in Danish history and culture.

As artist and art historian Eddie Chambers observed in his book Black Artists in British Art, the use of the word “black/Black” as an adjective, noun or racial description is a complicated matter. Historically as well as geographically, it is marked by shifting uses, identity politics and “strategizing”. Especially in a British context, the term “black” (with a lower-case “b”) has often been used as referring to peoples of African, Asian, South East Asian, Latino and Native American descent. Conversely, “Black” (with an upper-case “B”) has usually been deployed to denote, in the words of artist Gen Doy, “Black as a proudly chosen identity, history and culture associated with African roots, distinguishing the term from a simple adjective ‘black’ describing colour”.8 To underscore the political implications of the ways in which the term is used by people who self-identify (or are in turn identified by others) as “Black”, and to avoid confusion with “black” as a descriptor of colour (in works of art), I follow Chambers and write “Black” with a capital “B” throughout the text (except in direct quotations where the original spelling has been maintained). For the same reason, I occasionally write “White” with a capital “W” in comparisons with “Black” when I wish to underscore that the former is also a politicised and racialised term, not a mere descriptor of (skin) colour.

A body out of place: Adrian Piper’s The Mythic Being

Adrian Piper is one of the outriders of the feminist movement that emerged and consolidated itself in the late 1960s and early ’70s, and which “tended to focus on and make use of women’s bodies”.9 In 1973, Piper began to appear periodically in the streets of New York as a persona she called The Mythic Being. Dressed in a moustache, an Afro wig, mirrored sunglasses and with a cigar in her mouth, she appropriated elements of the popular image of Black machismo. In the images of The Mythic Being, Piper’s fair-skinned figure blurs the distinction of both gender and race, as the character conforms to neither racial nor gender norms. This has led the specialist in African American art history John P. Bowles to suggest that Piper’s queering of gender identity and her performance as a man of indeterminate race enabled her to transgress the limits that restricted Black women: she could “act as a man” and explore the masculine part of her personality and body, thereby negotiating social norms and articulating herself outside of the normative ideology of race and gender.10 In doing so, Piper also deliberately enacted a role that would make many people around her recognise and categorise her as what the feminist scholar Sara Ahmed has termed a “body out of place” or a “stranger” who may not only awaken the fear and insecurity of the people she encounters, but whose “transgressive” presence may also destabilise the racialised lines of demarcation between familiar and strange bodies.11

Such racialised distinctions not only determine social interaction between people in everyday life, they are also inscribed in national history and mark the borderlines of nation space in the narratives of who “we” are, and who “belongs” in “our country”. In the following, I examine how art’s potential to transgress such boundaries can open a space for people of colour and for new narratives of belonging to the predominantly White histories and spaces of European societies. This overarching question of how art can provide us with some of the images and conceptions needed to build a more capacious notion of the national “we” is primarily explored through analyses of works by Jeannette Ehlers and the Virgin Islander artist La Vaughn Belle, with whom Ehlers co-created the memorial I Am Queen Mary.

Questioning the history of Danish colonialism

Like many contemporary artists – including Danish-based artists such as Nanna Debois Buhl, Michelle Eistrup and Gillion Grantsaan – Jeannette Ehlers has taken a postcolonial and decolonial approach to formerly overlooked or suppressed aspects of the past that have never been acknowledged as part of national histories in order to create an alternative archive of Black histories. Ehlers has examined the history of Danish colonialism with a view to increasing the recognition of the country’s involvement in European colonialism, especially Denmark’s part in the profitable transatlantic slave trade and the atrocities of chattel slavery. To attain this goal, Ehlers has made the Black body and Black empowerment, and a postcolonial critique and decolonial liberation of consciousness, important components of her practice. Before proceeding, however, a note on how I am situated in relation to Ehlers’s artistic project is therefore in order. From an identity-politics perspective, it could be argued that a white Danish art historian, such as this present author, is not only subject to but is also a representative of the hegemonic whiteness Ehlers criticises and the colonial structures she seeks to change. My attempt to develop an analysis that encompasses the outlook and goals of artists whose experience of racialisation I do not share could thus be perceived as a misplaced act of “speaking for others”.12 However, my intention is not to speak on behalf of Ehlers and Belle (they do this eminently well themselves), but to place their work within a wider context of contemporary social transformations and challenges that affect all members of Danish society. German social scientists have crystallised these changes into the idea of postmigration, encapsulating a set of problematics related to identity, history, belonging and community originating in the obsession with migrants and immigration that permeates contemporary European societies.13 I will return to this concept in the conclusion and use it to elaborate how Ehlers’s critique of colonialism coincides with the evolving pluralisation of Danish society. Furthermore, I am aware that, although Ehlers and I are both Danish citizens, our experience of what this means is very different because of the pervasive racism against people of colour, immigrants and Muslims that continues to haunt all levels of Danish society as a result of the lack of the political determination to transform the ingrained structures and habits that produce the conditions for racism.14

Below, I elaborate first of all on the historical context of Ehlers’s works and the theoretical framework of my analyses before moving on to examine the live version of Ehlers’s performance Whip It Good from 2013 and the video-based version made the following year in and for the Royal Cast Collection in Copenhagen, a part of the National Gallery of Denmark, SMK. In these performances, Ehlers explored the legacy of colonialism and slavery – and Denmark’s romanticised part in both. I then turn to the thematically related collaborative sculpture I Am Queen Mary. Ehlers originally initiated this project around 2015, in connection with the migration studies scholar Helle Stenum’s plans for the exhibition ”Warehouse to Warehouse”. The exhibition was planned for two colonial storage houses in Denmark and St. Croix, one of the three islands known as the Danish West Indies until 1917 when Denmark sold the islands to the United States, after which they were renamed the United States Virgin Islands. The exhibition did not materialise, but if it had succeeded in attracting sufficient funds, it would have included two commissioned monuments by Belle and Ehlers. However, the plans did give birth to ideas that would feed into the two artists’ later collaboration.15 In 2017, late in the process of conceptualisation, Ehlers decided to develop her sculpture from a single-authored work into a collaboration with Belle. The year 2017 was the centenary of the transfer of the Danish West Indies to the United States, and it was extensively commemorated and debated both in the United States Virgin Islands and in Denmark. Ehlers and Belle’s memorial was unveiled the following year on Transfer Day (31st March) as the first monument in Denmark to commemorate those who were subjected to Danish colonialism and its trade in enslaved people.

From the 1660s until the beginning of the 1800s, the Kingdom of Denmark‒Norway was engaged in the triangular trade that involved the exportation of firearms and other manufactured goods to Africa in exchange for enslaved Africans, who were then transported to the Caribbean to staff the sugar plantations. The final stage of the triangle was the exportation of sugar, rum and other goods to Denmark‒Norway. However, the narrative of the Kingdom of Denmark‒Norway as a “benevolent” coloniser with an “enlightened” role in the abolition of slave trade and slavery has reigned supreme until recent years. In the years leading up to the centenary, critique of the Danish slave trade and colonialism, and debates about the afterlife of this dark past in light of today’s racism and social inequality, had been building up among artists, scholars and activists, preparing the ground for a shift in Danish memory cultures of colonialism. The centenary intensified these debates and led to an increase in postcolonial critique in public debates, newspapers, broadcast media and exhibitions, turning 2017 into a long-postponed moment of collective national self-scrutiny.16

Ehlers is the daughter of a Danish mother and a father born in Trinidad. It is her identification with the Caribbean and its legacy of slavery, colonialism and revolt that has impelled her to interrogate the history of slavery. This attachment and dual heritage also help to explain why Ehlers ‒ a Danish citizen who has been raised in her mother’s country of birth ‒ decided to transform her planned sculpture into a transnational collaborative work.

In her artistic practice, Ehlers proposes an alternative, revisionist perspective on national history: that of the colonised. Although the title of Ehlers and Belle’s memorial, I am Queen Mary, subtly plays on the fact that the current Crown Princess of Denmark is named Mary, it is not a monument to the Danish constitutional monarchy but, rather, a subversion of European notions of royalty. In the Caribbean, “queen” became an honorary title of the tough women who were the heads of the social life on the plantations. The memorial pays tribute to Mary Thomas, one of the four women who led the 1878 rebellion of plantation workers in St. Croix, where the awful conditions had improved very little since the abolition of slavery in 1848. The rebellion left half of the city of Frederiksted and many plantations burned to the ground. It was brutally quelled by the local Danish authorities, and the four women instigators were sent to a prison for women in Copenhagen until 1887, when they were sent back to serve the remainder of their life sentences in St. Croix.17 Today, they reign as legends in the history of the Virgin Islands.18

The cultural space of the African diaspora

Although Ehlers’s works are fuelled by an anti-racist awareness of the Western history of racial discrimination and violence, her works are multi-layered and open to different interpretations, and her audience-involving performance Whip It Good was emphatically so. Whip It Good was first commissioned by Art Labour Archives as a contribution to the event “BE.BOP: Decolonizing the ‘Cold’ War” at the Berlin theatre Ballhaus Naunynstraße in 2013.19 BE.BOP is an acronym for Black Europe Body Politics, a decolonial curatorial initiative by the curator, writer and scholar Alanna Lockward, who is also the founder of Art Labour Archives. BE.BOP functions as a forum for exchange and coalition-building among a network of artists, cultural workers and scholars mostly based in Europe, the Caribbean and the Americas. Ehlers came on board in 2013 and acted as guest curator of the Copenhagen BE.BOP event in 2014.20 It is thanks to Ehlers that BE.BOP seminars and art events have been held in Copenhagen in 2013, 2014 and 2016, closely coordinated with those in Berlin.21

As the international relations scholar Robbie Shilliam has observed, the notion of the “Afropean” is central to BE.BOP. This notion derives from the situation of living in Europe and “is meant to signal the emergence of a particular Black Consciousness in continental Europe from a Pan-Africanist perspective”. Shilliam explains:

Unlike the USA, the UK, the Caribbean and Latin America, the Black Diaspora in continental Europe cannot comfort itself with being an accepted community within the nation at large, not even a pathologized one. In this regard, the ‘Afropean’ brings the Black, African or Afropean community into a particular resonance with respect to Diasporic Aesthetics. It has a related but distinct place vis-à-vis hegemonic US-focused academic discourses, and also in relation to Black British cultural studies à la Stuart Hall.22

The Afropean is thus to be perceived as a specifically continental European phenomenon, a regional discourse. Charl Landvreugd, a Dutch artist of the African diaspora, has added to Shilliam’s circumscription a definition of the term Afropean as denoting a particular kind of embodied subjectivity nested in a European cultural form of “Afroness”, which finds a collective counterpart in “Afropea” understood as an imagined cultural space or imagined community. Judging from Ehlers’s works and her collaboration with Belle and Lockward, Afropea is the hybrid space Ehlers inhabits as an artist for whom “Afroness” and “Europeanness” are equally important to her artistic persona and sensibility. Or, as Landvreugd puts it:

In Afropea, the Afropean is the diasporic subject who transcends social and political circumstances of her Afro-Europeanness and claims humanity through cultural practices. The resulting subject is a European individual centralised in Afroness that takes Europeanness as an inherent quality and part of its subjectivity as an Afro multiplicity.23

“Outsiders inside” and the boundaries of the national “we”

It is no coincidence that Ehlers’s work is informed by decolonial thinking, as one of its protagonists, Walter Mignolo, has been a regular participant throughout the BE.BOP events.24 Decolonial thought is thus an important key to understanding Ehlers’s works, as is the broader field of postcolonial critique. Like postcolonial theory, decolonial thinking emphasises that colonialism and coloniality (i.e. the repercussions of colonialism on the present) constitute what Mignolo has called “the darker side of Western modernity”, and that coloniality and modernity are co-constitutive of one another.25 However, decolonial approaches are more concerned with self-empowerment. The aim is to decolonise the mind and “de-link” from Western and colonial ways of thinking in order to change “the terms and not just the content”, as Mignolo has phrased it.26 Both Mignolo and Lockward claim that decolonial thinking seeks proactive ways to empower people to “liberate” themselves, and perceive, inversely, postcolonial theory as merely reactive and aiming to “‘correct’ something that was ‘wrong’”.27 Although this is arguably a crude distinction that obfuscates the considerable overlap between the two, it helps explain why decolonial thinking is characterised by a strong emphasis on art and aesthetics as a means of changing historically determined parameters, making it obviously pertinent to Ehlers’s work. The distinction also suggests a possible cause of the somewhat surprising similarity between decolonial discourses and those of the Western avant-gardes: both make radical calls for a liberation of consciousness, the senses and artistic practices.28 Furthermore, as we shall see, reactive critique is also integral to decolonial aesthetics ‒ in Ehlers’s case, to the extent that the work may become what art historian Mathias Danbolt has termed an “enactment of retribution”.29

In the field of postcolonial theory, Sara Ahmed has introduced the concept of “strange encounters” and the figure of the “stranger” to examine how processes of recognition produce racial difference and social exclusion in situations of proximity. Contrary to the common intuition that a stranger is somebody you do not know, Ahmed proposes that strangers are products of techniques of recognition: strangers are those whose bodies are recognised as “being out of place”, such as black and brown bodies in spaces marked as White, as many social spaces are in Caucasian majority countries such as Denmark. Ahmed explains:

There are techniques that allow us to differentiate between those who are strangers and those who belong in a given space (such as neighbours or fellow inhabitants). Such techniques involve ways of reading the bodies of others we come to face. Strangers are not simply those who are not known in this dwelling, but those who are, in their very proximity, already recognised as not belonging, as being out of place. Such a recognition of those who are out of place allows both the demarcation and enforcement of the boundaries of ‘this place’, as where ‘we’ dwell.30

Ahmed asserts that the figure of the stranger is produced through relations of proximity. In other words, she distances herself from an essentialist understanding of differences as something that is simply found in bodies by stressing that difference is also a practice and technique of establishing relations between bodies.31

Directing her attention to contemporary societies, Ahmed suggests that globalisation, migration and multiculturalism operate as a specific historical mode of proximity that produces the figure of the stranger as the “outsider inside”.32 It is the outsider inside who marks out today’s boundaries of communities, dwelling and belonging. The process of marking out these boundaries involves strange encounters with the outsider inside that reopen prior histories of cultural encounter and evoke “histories of the stranger’s body”. According to Ahmed, these histories predefine the parameters of recognising some bodies as different from the familiar body that translates, in Ahmed’s own case studies, into either a local white community or the “we” of the nation.33 In other words, historical perceptions of and demarcations between groups continue to inform bodily encounters between people in the present. However, Ahmed makes a point of stressing that these bodily encounters are not fully determined by the past, thereby opening the door to change. Jeannette Ehlers’s works may give us an idea how art can actualise such change.

Decolonising the museum

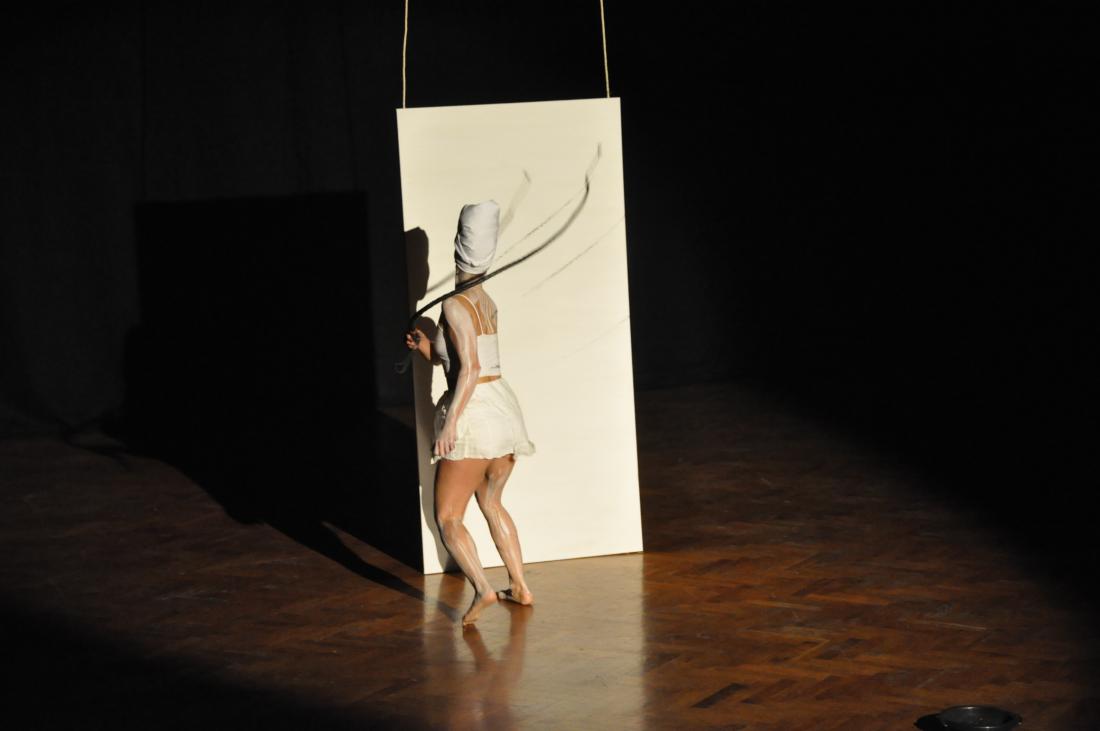

In the performance Whip It Good (2013), [fig.1] Ehlers re-enacted one of the slavery era’s most brutal forms of punishment – flogging – as a symbolic act. Staging transgenerational memories of the corporeal violence and suppression resulting from chattel slavery, the artist flogged a white canvas with a whip smeared with black charcoal and ended her performance by inviting the mixed audience to help her “finish the work”. [fig.2] Whip It Good thus transgressed several boundaries, including those between performance art and collective ritual, the artist’s body and the bodies of the spectators, between “Black” and “White” experience, and victim and perpetrator. The performance also reconnected colonial history with a postcolonial context, and absent bodies with bodies present. These transgressions ensured that the re-enactment would not be a mere reiteration of memories of a dark past, but a transformative act.34

The transgressions also produced strange encounters. Ahmed emphasises that “eye-to-eye” or “skin-to-skin” encounters are always mediated – by history, social norms, gender codes, cultural representations, and so on. This is worth bearing in mind here, where we are concerned with a female performer who has appropriated and re-enacted the role of a man: that of the punishing (often white) overseer of slaves. In Whip It Good, Ehlers thus used her ambiguous status as both a real-life person and a theatrical representation to shift the boundaries of both racial and gender conventions and link her work to feminist critiques of the idealisation of violently expressive masculinity which have claimed the right to deploy a “masculine” aesthetics of violence and anger – such as, for example, Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tirs or “shooting paintings” from the early 1960s,35 and Carrie Mae Weems’s staging of herself in the role of a militant Black nationalist in “Elaine” of the series Four Women (1988).

The white canvas ensured that the associations with white skin, and with easel painting as a Western hegemonic art form, came readily to mind. The fact that it was a Black woman who was flogging the canvas spawned associations with righteous anger and the rejection of Western traditions, even retribution. As Danbolt has noted, Ehlers staged “a scenario where the execution of art takes the form of punishment, and where the execution of punishment takes the form of an artwork”.36 At the same time, Ehlers turned to another tradition that is still practised across the continent of Africa: the tradition of using the skin as a black canvas to be decorated with body paint on important social occasions. As in some West African rituals, Ehlers employed white paint to symbolise cleansing. The paint also underscored the similarity between the surface of her body as the “ground” of body painting and the canvas as the “skin” of painting: both functioned as symbolic sites of negotiations between “Black” and “White”.

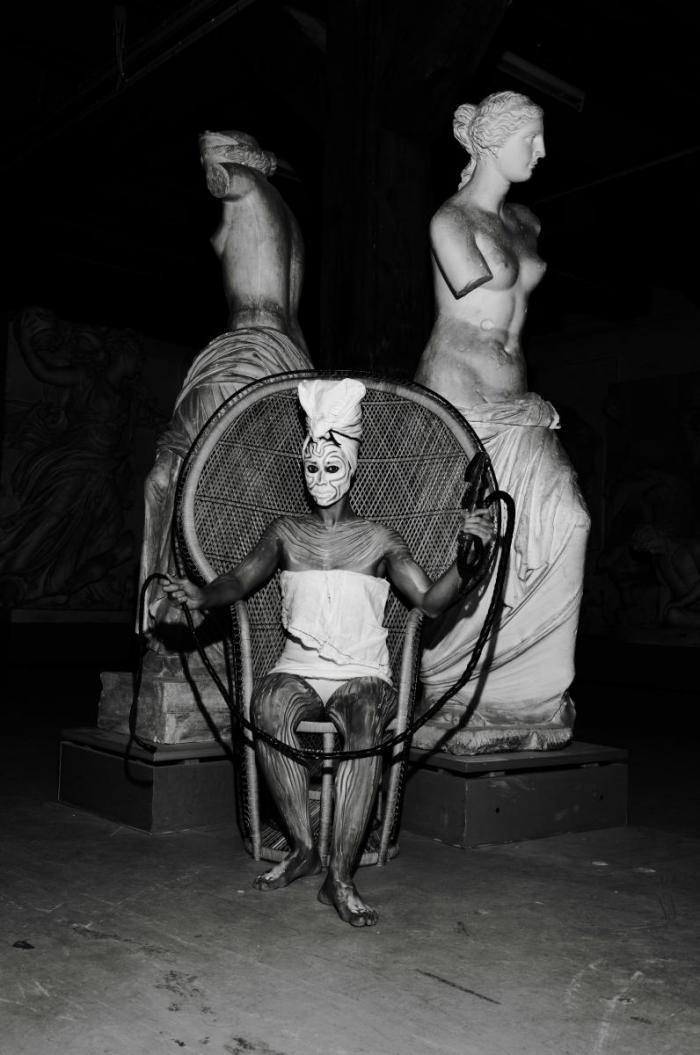

The decolonial gesture of delinking from the canon of Western art history and colonial mindsets was accentuated when Ehlers enacted the videotaped version of the performance among the white plaster casts of canonised Western sculptures in the Royal Cast Collection. [fig.3] Since 1984, the collection has been housed in The West Indian Warehouse (Vestindisk Pakhus), formerly used for storing colonial goods from the Antilles. The collection was founded in 1895 and included in the National Gallery of Denmark, SMK, in 1896.37 At that time, the European countries were still colonial powers, and the pervasiveness of the colonial mindset ensured that European cultures were ranked as incomparably superior to any other. Museums of art have been complicit in articulating this sense of Western superiority and linking it firmly to the superiority of whiteness. As the art historian Jeff Werner has suggested, the whiteness of art museums derives primarily from “their construal of both white art and the white body as the norm” and from “their praxis of instituting, establishing, and reproducing whiteness”.38 This is abundantly visualised by the whiteness of the plaster casts in the Royal Cast Collection. Accordingly, Ehlers’s performance can be seen as a decolonial intervention into the hierarchies of art history and the whiteness of art in European/Danish institutions. As a site-specific intervention, it also deployed the history of the site and the collection to rewrite the historical narrative in such a way that art history and colonial history were entwined.39 Thus, Whip It Good comes across as a powerful institutional critique that suggests a colonial mindset is still at work in art and in its institutions, a critique that seeks to change the terms and not just the content – as did the memorial I Am Queen Mary.

Claiming a space for Black subjects and histories

The locational connection between the video work and the monument points to the paradoxical nature of contemporary institutional critique. Disruptive interventions such as Whip It Good and I Am Queen Mary are only accommodated within the space and with the support of art institutions ‒ in this case, by the SMK ‒ because some of the professionals in the institutions have recognised the need to confront the colonial heritage and its structures. Ehlers’s critique is, therefore, not an autonomous act of protest but is, rather, predicated on mutual interests and a certain readiness for change within the museum itself, although this is no guarantee of durable transformation.40

While Whip It Good was performed inside The West Indian Warehouse, Queen Mary resides outside the colonial building on the harbour front, close to Amalienborg, the Royal Couple’s winter residence. For the duration of its installation, the memorial will thus remain in the full public view of Danish citizens and the thousands of tourists who visit the area. Here, Queen Mary will present herself to visitors as a female companion to the bronze copy of Michelangelo’s David, which has been placed in front of the warehouse to signalise what it stores today.

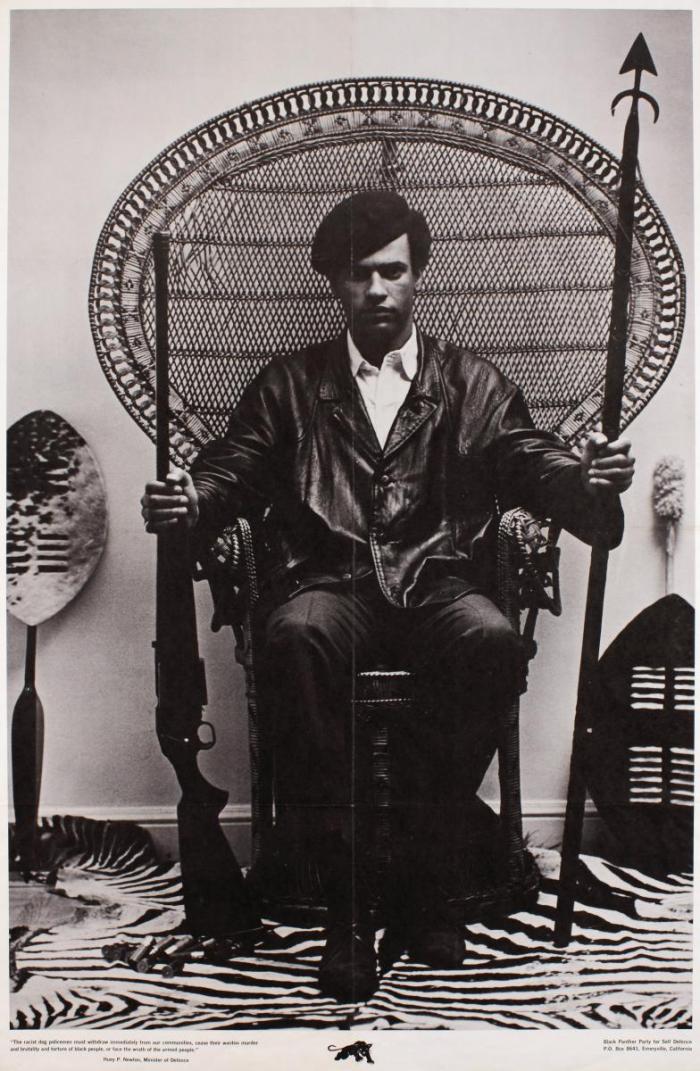

In connection with the recording of the video, Ehlers posed for a self-portrait to be used to advertise her solo exhibition in Copenhagen the same year. In retrospect, the photograph can be read as a staging of the artist as a Caribbean queen. Posing in front of the white plaster casts of the Royal Cast Collection, Ehlers sits enthroned in a large, wicker peacock chair. [fig.4] She is wearing her costume for Whip It Good and holding the whip in her raised hands instead of the royal regalia of sceptre and orb. Ehlers’s self-portrait alludes to a famous photo of the African-American activist and co-founder of the Black Panther Party, Huey P. Newton, posing like a warrior in a similar chair, spear in one hand, and rifle in the other. [fig.5] By allusion, Ehlers stages – and identifies – herself as an heir to the black revolutionary movements. Notably, she refers once again to a male figure and blurs the distinctions of both gender and race, not unlike Adrian Piper in her incarnations of The Mythic Being.41

Ehlers and Belle used this staged self-portrait as a model for their sculpture in which they literally and metaphorically embody a heroine of the Caribbean anti-colonial rebellions. However, the intersections between gendered, racialised and national identities are more complex than in the photographic image. Firstly, Queen Mary’s insignia, torch and cane bill have been substituted for the suppressor’s whip, thus subtly associating her with the image and spirit of Huey P. Newton as a more recent protagonist of Black rebellion and linking the sculpture to a more encompassing transnational and transatlantic history of African diasporic culture and Black resistance. Secondly, the female figure has itself been transformed into a hybrid of the physical appearance of the two artists; this was generated by morphing 3D images of their bodies, and subsequently used to produce the three-dimensional figure. Cut out of large blocks of polystyrene and coated in layers of sealant and black paint to reinforce the surface, the figure was made to look like a classical bronze sculpture.42 [fig.6]

Furthermore, the artists also recoded the traditional European plinth, i.e. the material and symbolic foundations of the sculpture, by drawing on a local colonial architectural heritage that Belle had explored in her own work: coral stones from the Virgin Islands, sourced from Belle’s historic properties, were incorporated into the plinth as a tribute to the enslaved who had been sent out at low tide to cut them from the ocean. The foundations of most colonial era buildings were formed of such coral stones. The plinth thus became an integral part of the monument, adding a poignant reminder that Danish colonial wealth was based on slave labour. [fig.7]

In her first project description, Ehlers described the sculpture as a “memorial” (mindeskulptur) – the first of its kind in Denmark, where there are no monuments dedicated to the Danish–West Indian colonial history.43 Ehlers argued that, for people of African descent, this absence of public commemoration amounts to a deprivation that reproduces the deprivation of identity suffered by the enslaved Africans who were forcibly displaced to the Caribbean.44 As she rightly pointed out, people’s understanding of history is not only shaped by what is taught in schools and exhibited in museums, but also by their daily use of objects and their sensory experience of sites of memory. With this memorial, Ehlers and Belle thus sought to raise consciousness about Danish–West Indian relations.

The extraordinary press coverage of the placement of this statue of a Black woman in public space suggests that the monument was considered a national and international landmark event.45 It should be mentioned that, unlike most monuments, I Am Queen Mary was not commissioned but owes its realisation to the tremendous effort of the artists not only to create the work but also to mobilise sufficient support and funds for the polystyrene sculpture, which the artists have suggested might one day be replaced by a permanent bronze sculpture. When the memorial was unveiled, opinions were divided on the question of permanence. It was argued, on the one hand, that the sculpture should be cast in bronze because a Danish tribute to the legacy of the enslaved and a public acknowledgement of the country’s colonial past were overdue, while on the other the monumentality of the figure was problematised. As the art historian Jacob Wamberg observed, “if she is cast in bronze, like David at the other end of the warehouse, she will be unbearably poisoned by the patriarchal authority from which we all may wish to be exempt”.46

Moreover, the feeling of menace that Queen Mary’s throne-like pose may instil into the viewers who are dwarfed by the monumental size of the figure is exacerbated by the statue’s ambiguous conflation of the visual language of violent rebellion with that of authoritarian rule. This opens the question of what to make of the memorial’s hybrid of the rebel and the ruler. As Michael K. Wilson and Mathias Danbolt have argued, the figure’s monumentality is counterbalanced by “visual signifiers of labor”: Queen Mary’s bare feet, her domestic clothing and the wicker peacock chair.47 However, these features do not anchor the monument unequivocally in the imagery of righteous popular rebellion, but the feeling is increased, rather, that the monument could also be read as a reminder that the authoritarian and colonial structures of the old regime may persist when insurgents become the new rulers.

National monument or counter-monument?

I Am Queen Mary commemorates the rebellions against Danish colonial rule and exploitation. Yet, as a memorial evoking “the darker side of Western modernity”, it does not fit easily into the category of the national monument, although I would argue that it does aspire to become one. Theories of counter-memory and the counter-monument developed in the field of memory studies may provide a more accurate framing of this work.48 In memory studies, the concept of the counter-monument has become an analytical lens for examining the construction of histories for the disenfranchised. The concept is founded in a Foucauldian notion of counter-memory as a recovery and reconfiguration of the histories of socially oppressed and marginalised groups. Thus understood, counter-monuments challenge the monolithic modes of collective remembrance and may open the category of the monument to more heterogeneous and democratic forms of remembering.49 As the art historian Veronica Tello has asserted: “Counter-memory fissures the singular and the homogeneous, allowing for the excess of the heterogeneous, so that it may become a site of disagreement”.50

In regard to national monuments, multi-layered articulations of counter-memory such as Ehlers and Belle’s memorial remind us that national collective memory is not set in stone but is, rather, an ongoing process of contestation, negotiation and selection. As the memory studies scholar Aleida Assmann has explained, it is forgetting, not remembering, that dominates society. To preserve the past in active memory requires a special effort, a re-enactment or commemoration of the past, often taking the shape of or needing the support of cultural institutions.51 Regarding Danish colonialism, “the problem is not that no significance has been attributed to the Danish‒West Indian past”, as cultural studies scholar Emil Paaske Drachmann has noted: “[t]he problem is rather that this significance is no longer considered relevant in a contemporary context. In Denmark today, there is a nascent break from the perception of history as the deeds of great men and a need to articulate Danishness as something else than blond hair and blue eyes.”52

I wish to propose that I Am Queen Mary challenges what the political scientist Michael Hanchard has termed “state memory”, understood as the generalising and centralising, institutionally supported narrative of the nation’s history. The monument subverts the patriotic narrative that glorifies the nation’s role in the abolition of slave trade and slavery.53 It “decentralises” this narrative and infuses a new transnational significance into the Danish‒West Indian past by staging a colonial and postcolonial encounter, where the “two” cultures of Denmark and the Danish West Indies/the United States Virgin Islands meet and merge through a performative process of hybridisation involving the bodily, identificatory and symbolic morph of Jeannette Ehlers and La Vaughn Belle. Moreover, the sculpture also merges the artists with their spiritual ancestor, Mary Thomas. Here, the historical struggle to overcome the detrimental effects of colonialism and the contemporary struggle for recognition and equality become two sides of the same coin. Thus, as a rewriting of Danish colonial history, the sculpture pays homage to the power of the suppressed and marginalised to change the course of history, both in times past and times present.

By “performing objecthood” (McMillan) and using her own body merged with that of Belle as a model for the sculpture, Ehlers made the sculpture gesture towards an expanded and heterogeneous notion of the national “we”, a notion capable of encompassing a community of citizens with diverse ethnic backgrounds and transnational affiliations. Such “co-ethnic” identifications are central to diasporic subjects and imagination. The merging of the artists’ bodies encapsulates a sense of self that, in the wording of literary scholar Ato Quayson, “is no longer tied exclusively to the immediate of present location but rather extends to encompass all the other places of co-ethnic identification”.54 Such affective bonds may be forged through various instruments of commemoration, which can be private heirlooms but also stories, rituals and public monuments.55 I Am Queen Mary is one such instrument, and reminds us that the nation-state and its population is criss-crossed by past and present transnational connections.

It is significant that this memorial pays tribute to a woman. By choosing Mary Thomas as their protagonist, Belle and Ehlers have contributed towards reducing the unequal representation of women and men in public monuments in Denmark, where only two per cent of the monuments representing named individuals commemorate women.56 As Belle has explained, “I Am Queen Mary represents a bridge between the two countries. It is a hybrid of our bodies, nations and narratives. […] Who we are as a society is largely about who we remember ourselves to be. This project is about challenging Denmark’s collective memory and changing it.”57

Peggy Phelan has captured wonderfully the hope that feminist art may inspire: “The promise of feminist art is the performative creation of new realities. Successful feminist art beckons us towards possibilities in thought and in practice still to be created, still to be lived.”58 Although Ehlers would not label herself a feminist artist, her work and collaboration with Belle resonates strongly with feminist strategies of emancipation. What both Whip It Good and I Am Queen Mary make evident is her strong commitment to emancipatory decolonial, anti-racist and feminist agendas.

Cultural diversity and the evolvement of Danish national identity

When we encounter others – and figurative sculptures – we perform acts of reading as we seek to recognise who they are by decoding the signs on their bodies, or their bodies as signs.59 As a female companion to the bronze copy of Michelangelo’s David, I Am Queen Mary puts into perspective the canonised ideal of beauty in Western art history. Although surpassed by her in size, David’s body represents the norm by which Mary’s body is measured: the Caucasian features, male gender and idealised proportions turn David into the perfect body “at home” ‒ the privileged, unmarked white body that simply belongs “in this place”.60 This, in turn, allows us to recognise Queen Mary as a “body out of place”. In its inaugural year (2018), I Am Queen Mary arguably appeared to be a “body out of place” in Danish art history. But what about the figure’s place in Danish society? [fig.8]

I would like to conclude by returning to Sara Ahmed, as Ehlers and Belle’s memorial resonates strongly with her understanding of “the stranger”. Ahmed has also considered the place of the stranger in multicultural societies, taking as her particular example Australia, a nation composed of many different immigrant cultures as well as indigenous peoples. Although Denmark cannot be considered a multicultural society like Australia, its demographic diversity is increasing; and this can also be seen in other northern European countries.61 Moreover, the most recent research indicates that the support for the previously hegemonic perception of Danish culture as a monoculture is waning, especially among young people. At the same time, the public debate on immigration and cultural diversity is very animated, but it is also very polarised: many people have a positive attitude towards immigrants, but there are also many who hold a very negative view.62 According to sociologist Christian Albrekt Larsen, the growing significance of diversity in the Danish national self-perception is, for the most part, the result of generational effects, and therefore to be considered irreversible. Based on a comparison of two large Danish surveys from 2003 and 2013, Larsen concludes that the citizens’ notions of the national seem to be “moving slowly but surely towards multi-culture”.63 Ahmed’s thoughts on the place of the stranger as a fellow inhabitant, incorporated into the “we” of the multicultural nation, thus provides an illuminating perspective on Ehlers and Belle’s memorial. This may help towards a realisation that the work’s potential extends much further than the mere transgression of the whiteness of European public monuments and the insertion of artists of colour into the history of Danish art.

One of Ahmed’s key points is that multicultural societies incorporate the stranger as a stranger within who has a place in the nation. Of course, tolerance alone cannot eliminate deep-seated differences and antagonisms between groups, nor does it prevent a contradictory process of inclusion and expulsion from taking place, resulting in the exclusion of what Ahmed calls “stranger strangers”. As opposed to the “familiar strangers”, the stranger strangers are considered to be “unassimilable”.64 Ahmed emphasises that, just like nations that consider themselves to be monocultural, Western multicultural nations are also founded on “a clear assumption of the importance of a ‘common culture’ to a ‘multicultural nation’”.65 What is important in our context is that the multicultural embrace of “strangers” alters and widens the scope of the national “we”. Ahmed describes this change as a two-sided process: when immigrants and their descendants, or indigenous groups, become incorporated into the “we” of the nation, that “we” emerges as the one who must live with cultural diversity and a plurality of ethnic groups.66

Recent German debates on “postmigration” can deepen our understanding of this slow move towards multi-culture (Larsen). The term “postmigrant” was first put into circulation as a critical term in the cultural milieu of Berlin between 2004 and 2006. Around 2010, it was adopted by academics, primarily in the social sciences, and developed into a theoretical concept and an analytical lens. German scholars use “postmigration” as a perspective on the ways in which past and present migration has transformed European societies (primarily Germany, and especially after the Second World War) – i.e. societies that are presently in the “belated” process of realising that they have become culturally diverse or “multicultural”. Several researchers, including a group of scholars based in Danish universities,67 use the concept of postmigration as an analytical category that relaunches migration and socio-cultural diversity as a state of normalcy and something that defines, involves and is of relevance to all members of society, regardless of individual backgrounds.

Contemporary art can reflect on and help audiences work through the difficult collective experience of becoming a more culturally diverse society, with all the conflicts it entails: struggles over individual, collective and national identity; against polarisation, discrimination and racialisation; and for equal access to recognition, resources and representation, etc. A crux of the postmigratory struggles is precisely the struggle against racism and for recognition of people of colour and their obvious place in European national histories, public spaces and cultural institutions. Jeannette Ehlers’s works and her collaboration with La Vaughn Belle should be counted among the groundbreaking contributions to this postmigrant struggle. As the first Danish monument to a Black woman, I Am Queen Mary tells the story of Queen Mary (Mary Thomas) and thereby commemorates women’s leading role in anti-colonial and labour revolts. It also expands the official “portrait of the nation” that public monuments constitute to include people of colour and those who have suffered under Danish colonial rule.

To understand art’s contribution to the postmigrant struggles for recognition, it is important to realise that there are two sides to the concept of postmigration: it denotes not only a historical condition but also a normative vision of a better society that has significantly improved its ability to recognise and manage its own diversity and inequalities.68 As my colleagues and I argue elsewhere, the dynamics that undergird this normative conception of postmigration as a process of collective (societal) self-improvement can be described in spatial metaphors.69 Briefly explained, postmigrant approaches are driven, firstly, by an ambition to clear space, as they seek to get rid of essentialist thinking and polarising distinctions, such as migrants versus non-migrants, majority versus minorities, and White people versus people of colour. Instead, postmigrant perspectives emphasise the intricate meshworks that connect people in multifarious ways. Secondly, they involve claiming space. Postmigrant initiatives work towards institutional equality and the inclusion of marginalised groups. However, the very act of “claiming” implies taking something back and therefore necessitates struggles and conflicts. As a result, the concept of postmigration does not refer to a harmonious multiculti-utopia, but to a conflictual process of societal transformation that entails renegotiation of, among others, collective identity and national history, including the difficult acknowledgement that colonial barbarism has been integral to European civilisation and the evolvement of modern nation-states. Thirdly, postmigration is propelled by endeavours to create space: some offer new analytical frameworks for understanding, some foster new types of coalition and collaboration that cut across the usual ethnic and social divides, and some create actual spaces and material sites of negotiation, including artworks that critically renegotiate the terms of representation and provide us with a sense of direction or passage into the future.70

I Am Queen Mary is one such site. The mere fact of its realisation and instalment in a public space rich in colonial history signals a nascent official acknowledgement of the need to rethink national identity, heritage and culture with a view to cultural diversity, although such initiatives are still contested by national conservative voices (the contestation itself being an indication of the conflictual nature of the postmigrant condition). Together, Belle and Ehlers act as a proxy for a Black “queen” whose name is linked to the historical injustices and violence of Danish colonial rule and who became a symbol of the enduring struggle of the oppressed for empowerment and social equality. As a work of public art, as a rewriting of history and as a new point of identification, I Am Queen Mary may open a space for people of colour and a possibility for new narratives of belonging to be added to the history and public space of a European country whose people are being challenged to learn how to live with cultural diversity. The memorial also represents a public recognition of women as leading and transformative figures in history and society – but this is another story, a history of gender inequality and the emancipation and power of women. It obviously intersects with the history of anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles, giving a feminist slant to the postcolonial, decolonial and postmigrant analysis elaborated above. A feminist reading would not contradict this analysis but, rather, underscore that the histories of suppression and disenfranchisement are multiple and intersecting, and that the protagonists of these histories are still underrepresented in public space.

Ehlers and Belle have thus put their finger on several problems of representation. They have cleared, claimed and created a space for Black subjects and histories in the public sphere with a monument that produces a wealth of meaning and hopefully inspires us (the new “we”) to move beyond the status quo. As bell hooks noted: to transgress, we must move past boundaries. ▢

Copy-editing by Nicola Gray

The top image is a detail of Jeannette Ehlers, Whip It Good, 2014. Still from a video-recorded performance. See fig. 3