Summary

Kristian Zahrtmanns Sokrates og Alkibiades, malet i 1911, har længe været bedømt som et billede på homoseksuelt begær og dermed som en repræsentation af Zahrtmanns egen seksualitet. Den helt særlige måde, Zahrtmann anvender Platons Symposion på, er derimod ikke blevet bemærket. Jeg vil argumentere for, at Zahrtmanns praksis adskiller sig fra andre måder at bruge den græske antik som apologi for eller symbol på homoseksuel kærlighed, både i måden den direkte refererer til omstændigheder i Danmark i begyndelsen af 1900-tallet, og som den indskriver sig i kunstnerens æstetiske og filosofiske tanker. Jeg argumenterer for, at Zahrtmann ikke fremstiller homoseksualitet i med eller mod tidens moralske og juridiske normer, men at han derimod, på et tidspunkt, hvor der i København er både systematisk, statslig undertrykkelse af homoseksualitet og en begyndende debat om seksualiteten, overvejer det etiske arbejde, der skal til for at imødekomme begæret i eget liv og praksis.

Articles

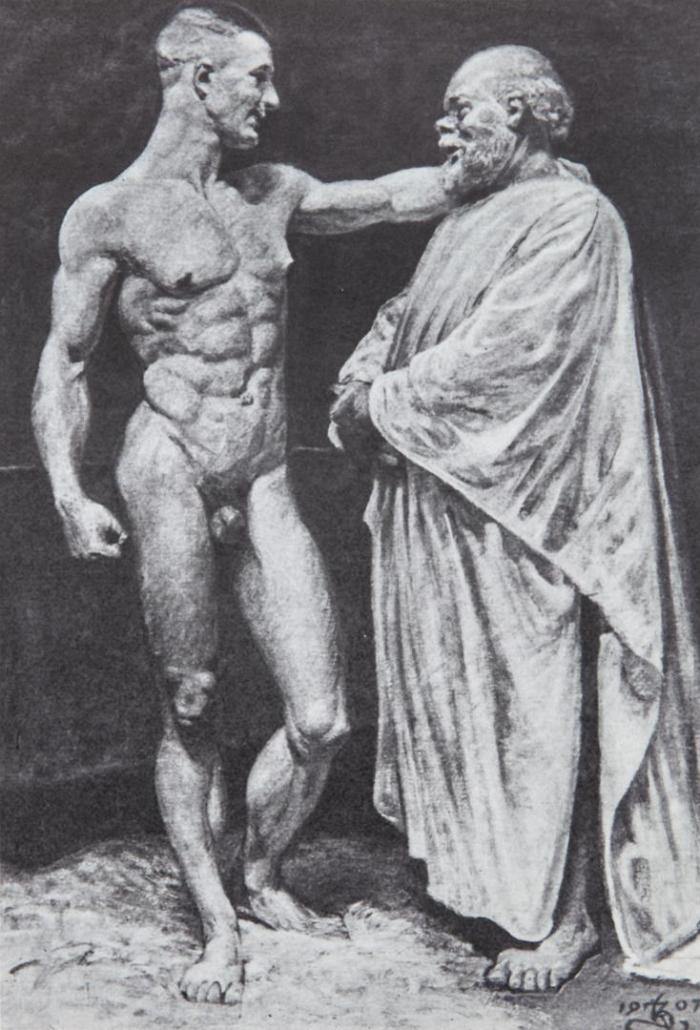

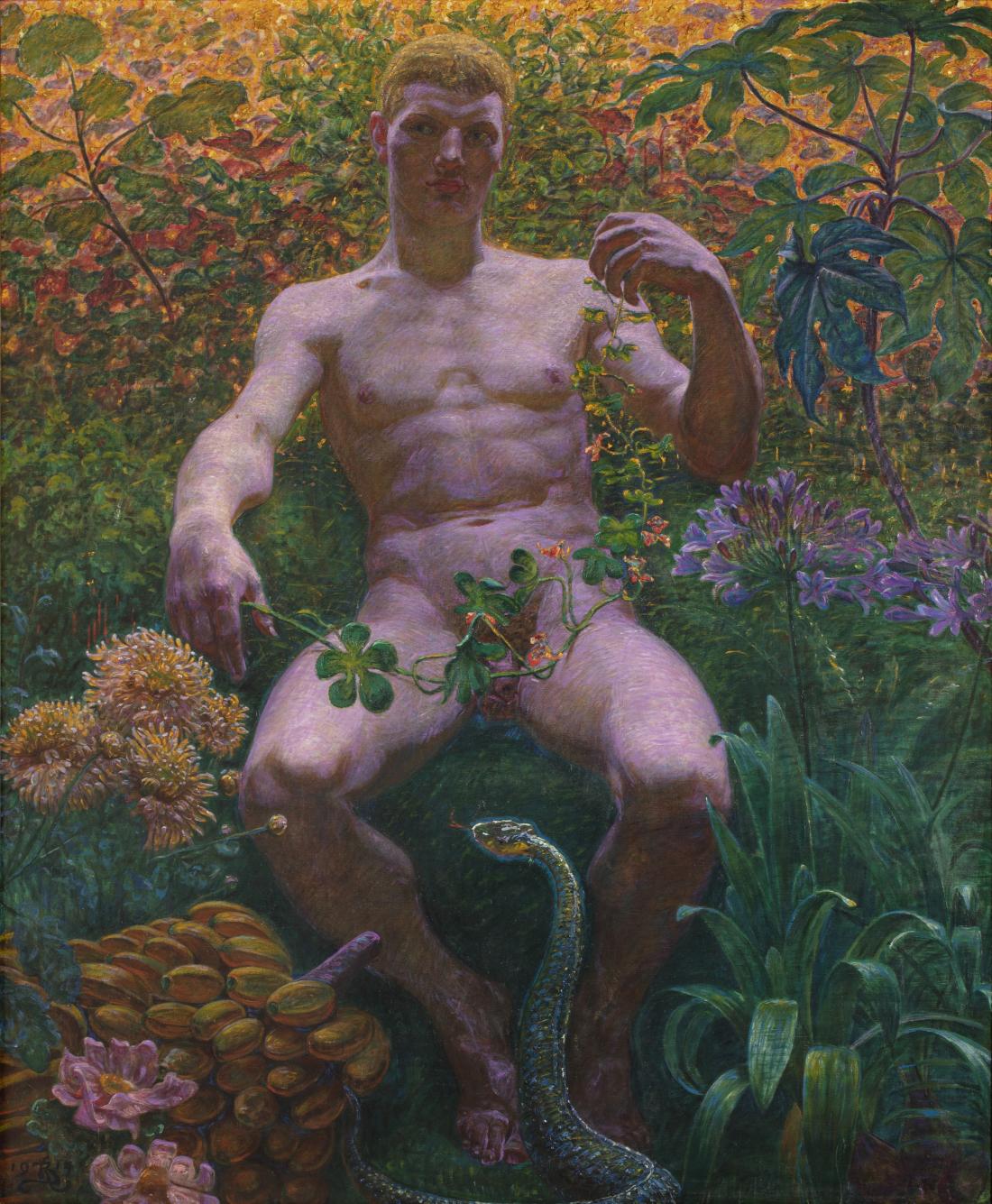

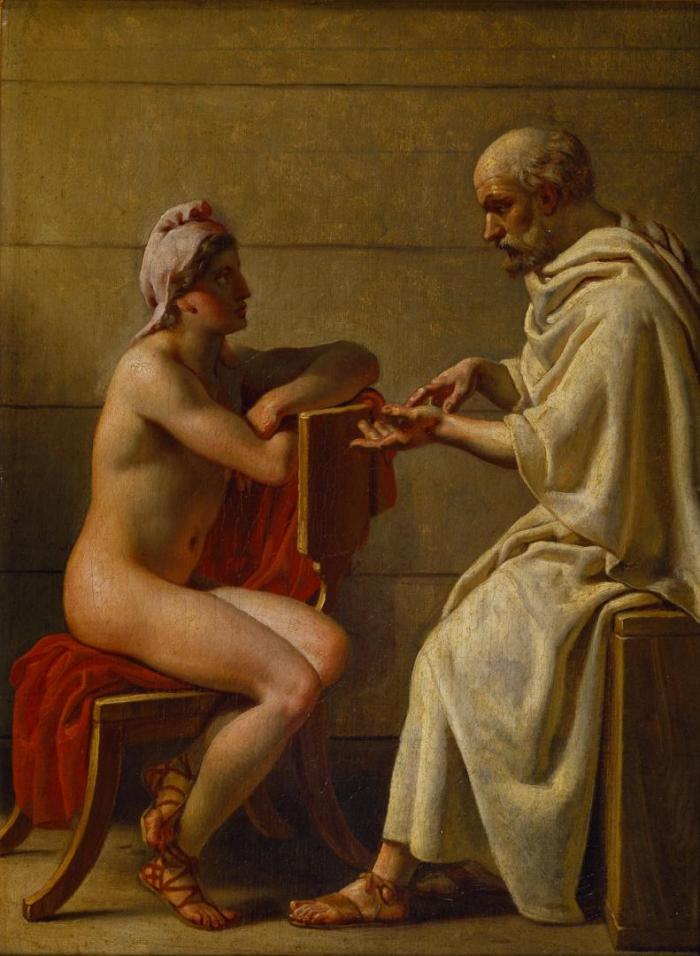

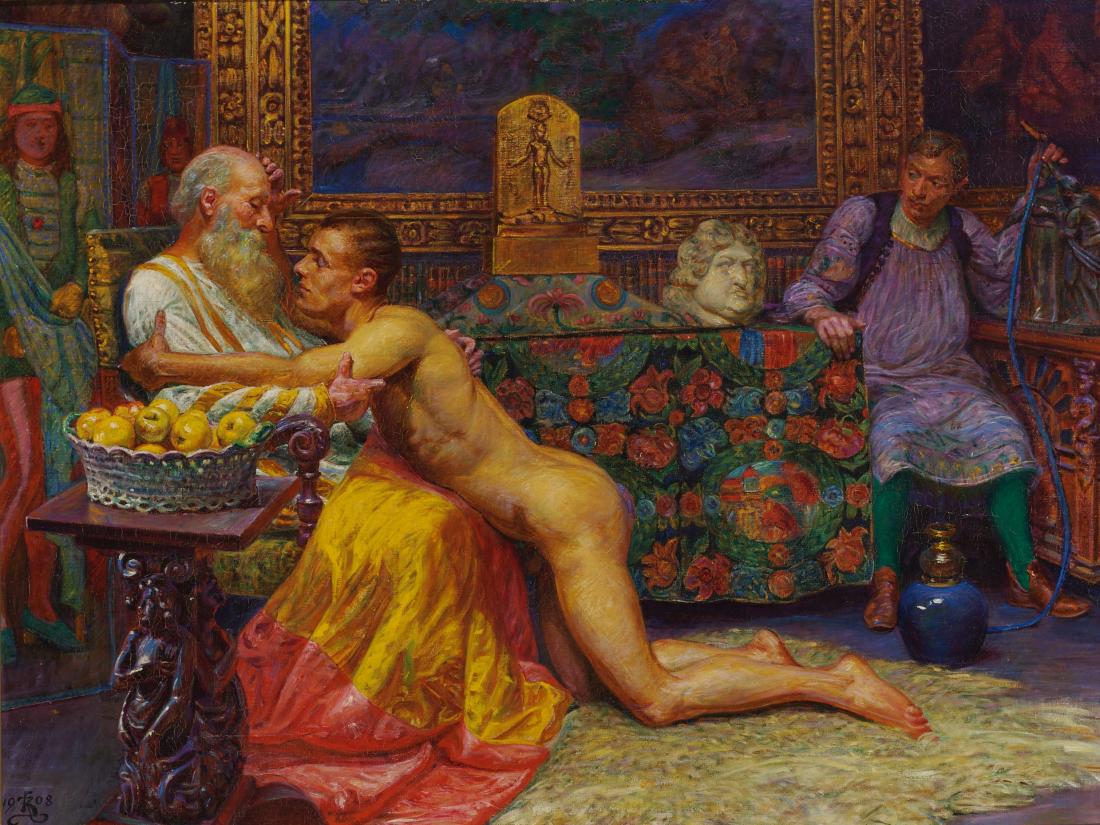

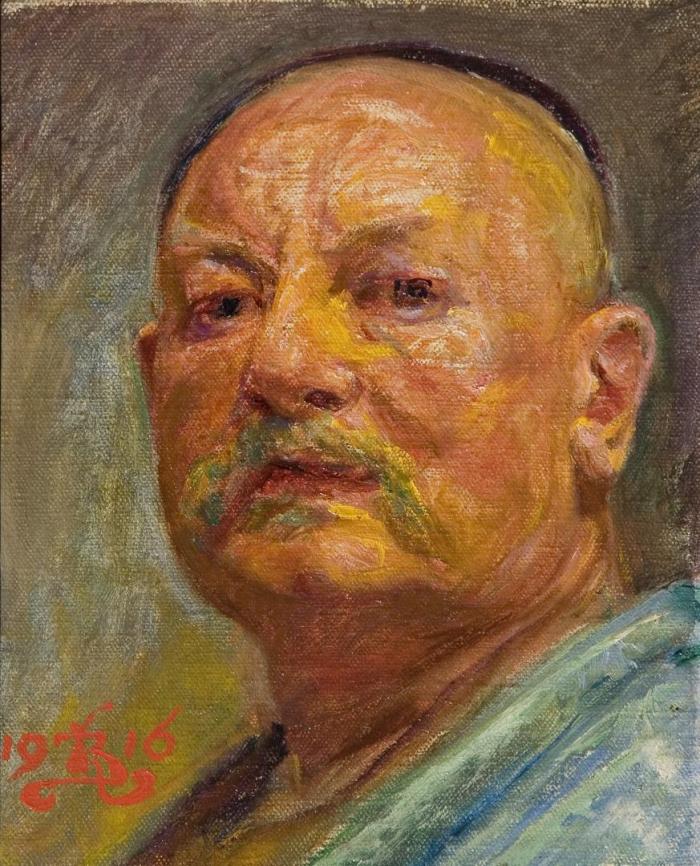

An older man, draped in a robe, holds a statuette, apparently lost in thought. While his fingers wrap around the form, his strangely gazeless gaze suggests interiority and a concern for the world of higher things [fig.1]. A younger man, muscled and naked, sits next to him and leans in seductively, as if asking him to replace the small figurine with the real thing, to exchange the cold bronze of the statuette for the warm flesh of a handsome companion. A smile flickers across the younger man’s face, as if he is aware of the irony of the situation: that his older companion chooses a search for intellectual satisfaction over the availability of the bodily.

Kristian Zahrtmann’s Sokrates and Alkibiades, painted in 1911, has long been recognised as a painting about homosexual desire and a representation of Zahrtmann’s own homosexuality.1 The scene is taken from Plato’s Symposium, which was, after all, one of the most widely used references for homosexual men through latter part of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. What has not been fully acknowledged, however, is the distinctiveness of Zahrtmann’s use of this source. This, I want to argue, is unlike other uses of Greek antiquity as an apologia for or a symbol of male homosexual love, both in its particular resonance in early-twentieth century Denmark, and in relation to Zahrtmann’s broader aesthetic and philosphical concerns.

My argument will be that Zahrtmann presents homosexuality not as a question of compliance with or resistance to codified moral and legal norms, but, at a moment of systematic state suppression of homosexuality and the opening of debate about sexuality in Copenhagen, he considers the ethical work needed to address and accommodate desire. As the irony of the painting suggests, Plato’s Socrates is not simply a symbol of a certain desire and its legitimacy, but much more a figure to be emulated in using desire to form the relationship to self and to others; those structures that Michel Foucault termed ‘the uses of pleasure’ and ‘the care of the self’.2

Copenhagen, Greece

Zahrtmann had first considered painting Socrates and Alcibiades in 1876, according to a letter he wrote to his mother.3 However, he did not tackle the subject until 1907 when he painted the first version, now lost [fig.2]. From the face-to-face encounter in that work, the second version, made in 1911, places the two men side by side. The paintings were both exhibited in Copenhagen. The later version was first shown in the art dealer Kleis’s March Exhibition in 1911, and the earlier version in the Free Exhibition in 1914, which included a retrospective of Zahrtmann’s work. Both paintings were also reproduced in various locations in 1911. The 1907 painting was included in an issue in the series Små Kunstbøger dedicated to 60 autotypes of Zahrtmann’s work, published by Gads Forlag, while the later one was illustrated on the front page of the newspaper Riget in February 1911, as a foretaste of the new works to be shown at the art dealer Kleis’s March exhibition that year.4 The first painting was also reproduced on the front page of the newspaper Social-Demokraten on March 29 1914, illustrating, along with other paintings, the large part of the Free Exhibition devoted that year to a retrospective of Zahrtmann’s work.5 The 1907 painting was bought by H. Chr. Christensen, one of Zahrtmann’s most important patrons and advocates, and the 1911 was sold by Kleis to E. T. Kiellerup at some point after 1913.6

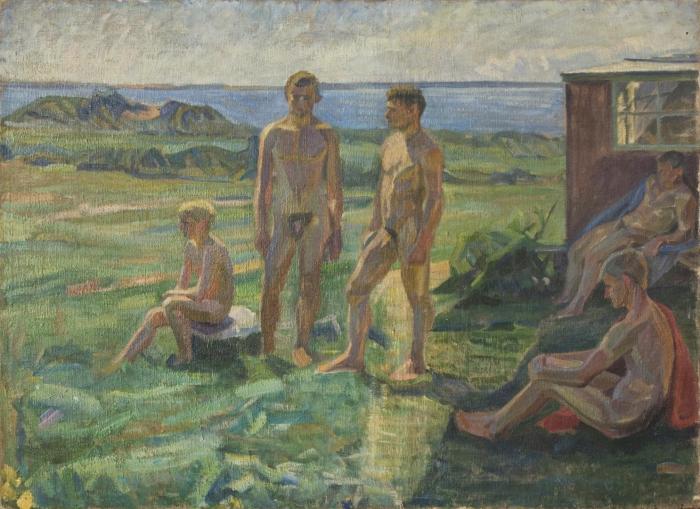

The subject, with its aura of homosexual desire, was clearly not, therefore, a hindrance to public display and discussion. Indeed, the paintings were made in the context of considerable enthusiasm for and scholarly interest in ancient Greece in early-twentieth century Copenhagen. As throughout Europe and North America, intellectual and artistic milieux were suffused with Hellenism. Ancient Greece appeared everywhere: in the collections of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, in the music of Carl Nielsen, in debates about education, and, of course, in the art world, most evident in the project of the Hellenes, led by Gunnar Sadolin, who tried to recreate Greek ascetic ideals in the rather chilly climate of Funen, Denmark [fig.3].7 The male nude was an essential part of this cultural matrix.

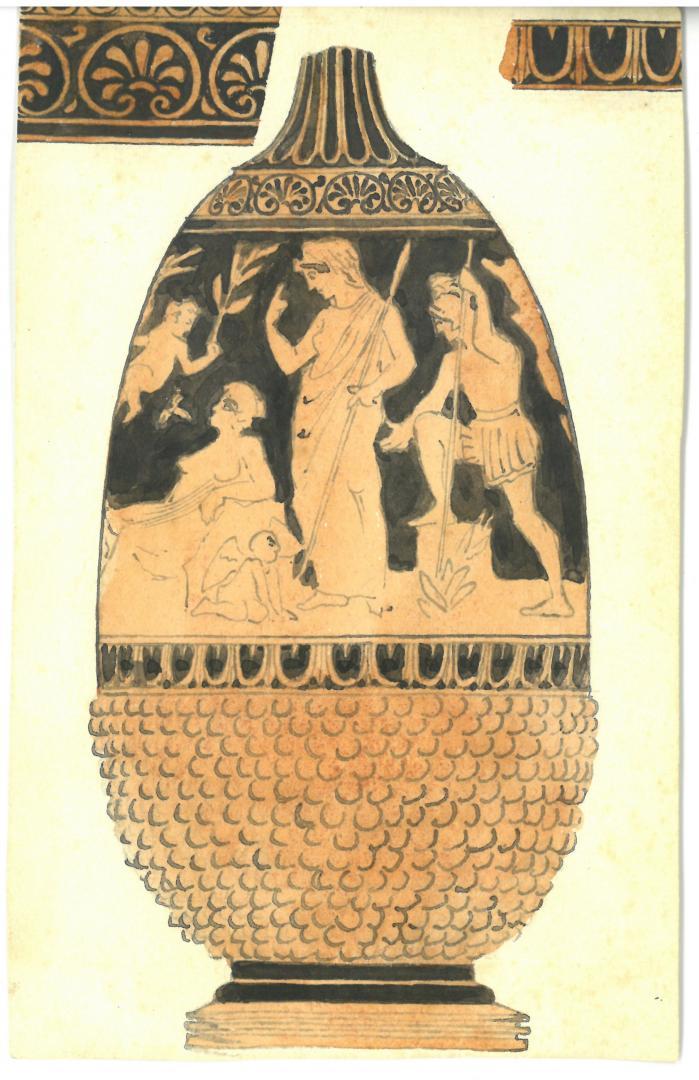

Zahrtmann was fully embedded in this Hellenophilic world. Schooled in the classics, and a very erudite man, he later claimed that Greek was his favourite subject at school; he was taught at the Sorø Academy by Rektor Bojesen, one of Denmark’s most important classical scholars, and remarked that he loved Herodotus, Xenophon and the tragedians.8 He studied Greek art both in Greece and in Italy, sending back drawings of vases to the ceramic manufacturer, Hjorth’s [fig. 4], and he taught Sadolin and the other Hellenes.9

Zahrtmann was also a member of the Greek Society, a group of intellectuals formed in 1906 for lectures and discussions. The society was an important institution for the promotion of knowledge about ancient Greece in Denmark.

The inaugural meeting was a lecture by Harald Høffding, Denmarks’ leading philosopher, about Plato’s Symposium. In his lecture, Høffding explained that it was the Symposium that had turned him into a philosopher: a story of origins pertinent to the first meeting of the society.10 SAs one might expect, Høffding’s lecture did not dwell on homosexuality; there is though a passing reference to Alcibiades’ attempt to ‘ensnare’ Socrates.11 Whether or not Zahrtmann attended Høffding’s lecture is not known, but he and Høffding were old friends; besides, the lecture was published in 1906 in Tilskueren, Denmark’s most important cultural journal at the time.

Two Danish translations of the Symposium appeared the following year, 1907. The first was by the classical scholar Hans Ræder, who, in the introduction to his translation, addressed the question of sexuality head on.12 He makes it clear, in the opening pages of his essay, that for the Greeks love was, first and foremost, conceived as between men, given the low, sequestered status of women and the social or political importance of male bonds. However, he goes on to suggest that this was not straightforward; he writes that Socrates ‘half in jest and half in earnest, would represent his relationship with the young man with whom he was consorting as a love affair, which he used to plant thoughts in the young man’s soul’.13 Homosexual desire was thus a means to an end, even if, half in earnest, the erotic content of Socrates’ self-image was not entirely a misrepresentation. Ræder’s translation appeared in Studier fra Sprog- og Oldtidsforskning published by Det Philologisk-Historiske Samfund, and in such a specialist scholarly journal there was scope for frankness. His readers would already have known something of ancient Greek sexual practices. Nevertheless, the references to homosexual practice do herald a change; in a 1905 book about Plato’s dialogues, Ræder had been much more reticent in his discussion of the Symposium, making no reference to homosexual desire.14

The second translation, by Martinus Gertz, was aimed at a broader educated public, one not restricted to the university and learned societies.15 The book received very favourable reviews in the daily newspapers, with one critic declaring that Gertz’s translation of ‘one of ancient literature’s most famous and most capitivating works […] arouses the greatest admiration’.16 In his introduction, Gertz skirts around the question of homosexuality, but, like Ræder, explains that the status of women, incarcerated in private, and considered to be no more than bearers of children and keepers of houses, meant that love was primarily understood as between older and younger men, often focussed on the naked bodies on display in the gymnasium. Gertz works hard to negotiate the slippery path between antique life and contemporary morals. He makes it clear that social ideas were very different in ancient Greece, and translates the work eros as both ‘elskov’ (love) and ‘attraa’ (desire/sexual craving). This enables him to distinguish between what, for a modern reader, might be the pure philosophical use of homosexual desire and the wicked deviant embodied in the flesh. Thus, in discussing Alcibiades’ eulogising of Socrates, he insists that the younger man’s relationship to the older is one of love rather than physical desire.

Thus, there was a rich and serious culture of engagement with Greek antiquity in turn-of-the-century Copenhagen, and Plato’s Symposium was an acknowledged and much discussed point of reference, particularly in the years when Zahrtmann was painting his pictures of Socrates and Alcibiades.

The Great Morality Scandal

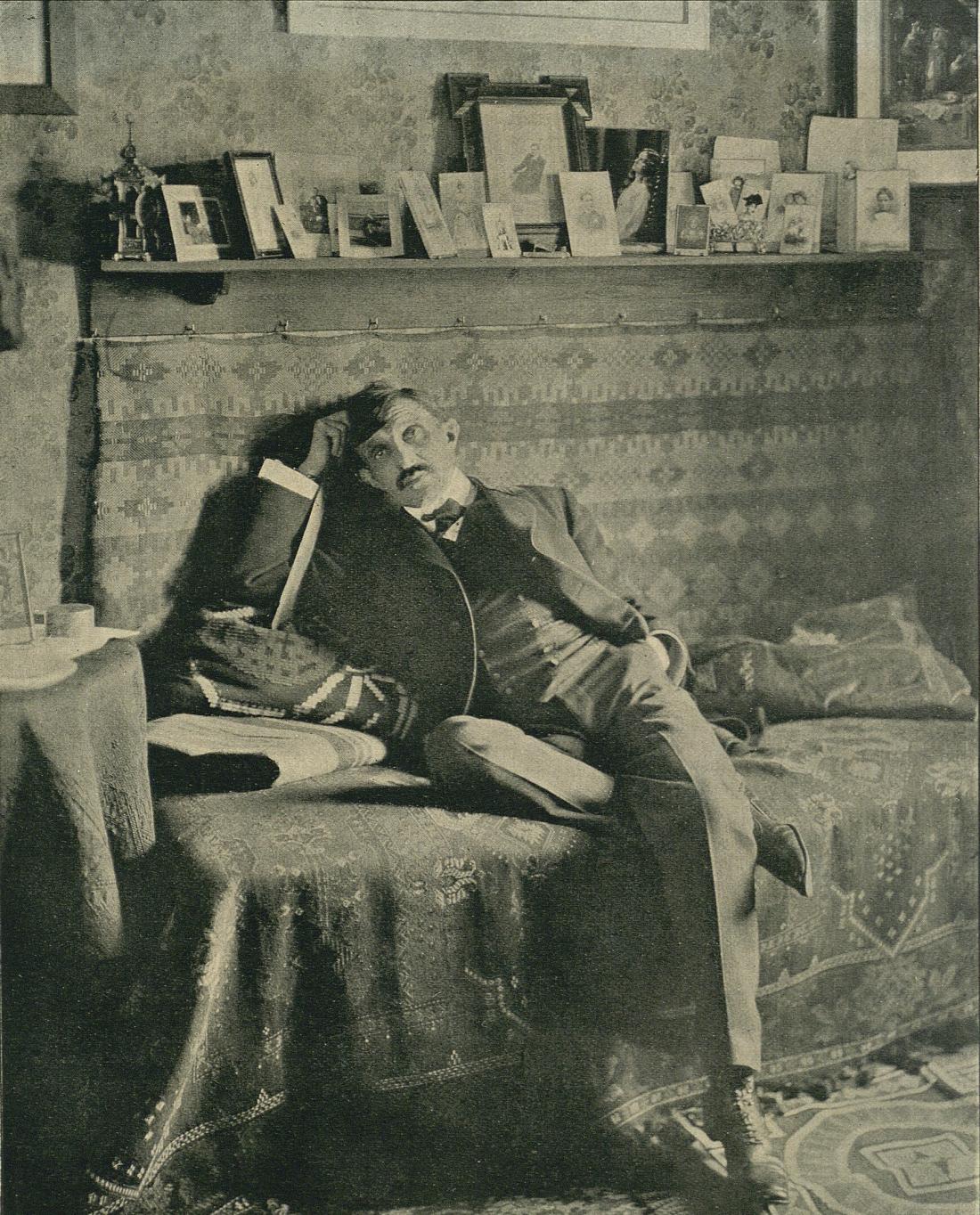

There is a second Danish context, however, that needs to be addressed, and one that makes the date of Zahrtmann’s paintings, 1907 and 1911, more striking. In 1906 the newspaper Middagsposten published a report about boy prostitution and male homosexual clubs in Copenhagen. This revelation developed into the so-called Great Morality Scandal of 1906-7, during which many men were arrested and prosecuted, and male homosexuality made a grand entrance into public discourse.17 Most scholarly attention has been paid to the implication of leading novelist, theatrical figure, and public intellectual Bang in the scandal. On 30 November 1906, the author and later Nobel laureate Johannes V. Jensen published a much-quoted article in Politiken, referring to a ‘well-known writer’ as a homosexual, an article that may have been the impetus for the naming of Bang in subsequent reports.18 Indeed, the next day another article in Middagsposten about the scandal cited Bang as ‘the most disgusting and dangerous homosexualist, […] the worst of them all’.19

Bang was indeed homosexual, and conformed to a familiar image of the aesthetic homosexual, in terms of his physical appearance, his refined concern for art and theatre, and his cosmopolitanism. As Lene Østermark-Johansen has pointed out in a very fine essay, he was a Danish parallel to Oscar Wilde, and in his photographs he often crafted a familiar aesthetic persona [Fig. 5].20 He had furnished other writers with a model of the homosexual aesthete, and figures in novels had been based on him. Jensen had presented thinly veiled caricatures of Bang as Zacharias in The Fall of the King (1901) and Evanston (also known as Cancer) in The Wheel (1905), while Daniel Larsen had used Bang as the template for the poet Kold in his anonymous novel Daniel-Daniela (written in 1906, although not published until 1922). However, while Jensen contrasted the feminised, feeble aesthete with the vigorous, healthy hero, a ‘homophobic vitalism’ as one critic terms it, this literary and moral battle was not straightforwardly about norm and deviance.21 It implicitly pitted two models of homosexuality against each other. Jensen admired and had translated the poetry of Walt Whitman, and had included some of the poems and discussion of them in The Wheel.22 Jensen excused Whitman’s evident homosexuality in light of the poet’s higher ideals, democratic principles and approach to modernity.23 Thus, in The Wheel two distinct readings of Whitman’s male bonds are presented: the healthy Vitalist version of the protagonist Lee and the demoralised Aetheticist version of Evanston, the character based on Bang.24

There was not only a huge number of articles in the press about the scandal as it happened, providing details of the crimes, trials, and convictions of the men who were targeted by the police; there followed a steady stream of articles about homosexuality in the ensuing years. Subsequent scandals were widely reported, most famously the Eulenberg scandal in Germany, but also more local events, such as those unmasking two churchmen, Pastor Mathiesen and Pastor Davidsen, as homosexuals.25 Emanuel Fraenkel’s The Homosexuals, the first book in Danish about homosexuality, was published in 1908 and was widely reported and positively reviewed in the press.26 This moral concern was evident also in the organisation of public meetings to discuss the problem, and to assess ways in which the law might be upheld or strengthened. Such meetings took place in regional centres, such as Studenterforeningen (?), but the most important was a large assembly held in the Concertpalæ in 1911. Nearly three thousand men listened to speeches about the moral threat of homosexuality from Frænkel and others, and resolved that the law against homosexuality must be tightened, lest Copenhagen, like Berlin, be tainted further by deviance. The proceedings were published under the title Our National Disgrace.27

Thus, Zahrtmann’s paintings of Socrates and Alcibiades were made, on the one hand, at a moment when the Symposium was much-discussed in polite cultural and intellectual circles, and, on the other hand, at a moment when homosexuality was the yet more widely discussed focus of a moral panic. At the very moment Frænkel was addressing the audience at the Concertpalæ, a short walk away in Vesterbrogade, the later version of Socrates and Alicbiades was on display at Kleis’ March Exhibition. Zahrtmann, like any Dane who read newspapers and lived in Copenhagen, could not have failed to be aware of the scandal and its aftermath. Moreover, this is a moment where he turns increasingly to the male nude in all its desirable muscularity. Were the paintings, in some sense, responses to the public debate and challenges to the condemnation of homosexual desire? Are they assertions of Jensen’s positive and healthy Whitmanesque idea of male sexuality? Or, in the absence of any documentary evidence should we eschew speculation and read the paintings as belonging squarely in the world of Høffding and the Hellenes and the Greek Society?

The Male Nude

Zahrtmann had already turned to the male nude as a favoured subject before the scandal erupted, and his work from the early years of the century, such as the painting of Adam in Paradise from 1914, have frequently been connected to Vitalism and the ethos of Jensen’s contemporary work [fig.6].28 Zahrtmann had known Jensen for years, both from Bogstaveligheden, the group of avant-garde artists and writers that formed around Georg Brandes in the 1880s, and because Jensen was a great ally of the Funen painters, who were taught by Zahrtmann.29 Jensen described the Funen painters as exemplars of health and vitality, the opposite of what he termed the ‘anaemia’ of the Symbolist painters Harald and Agnes Slott-Møller.30 Thus, the healthy, hale and hearty male body might be positioned as the Vitalist corrective to the droopy, bloodless Aestheticism of a figure such as Bang. However, while there are personal connections with his Vitalist contemporaries and superficial visual similarities, such as the turn to the male nude, Zahrtmann did not share the conceptual underpinnings of Vitalism. Indeed, rather than presenting the male body as an exemplar of health, instinct and the life force, Zahrtmann was primarily concerned with the ethical. In this sense, he was completely at odds with a thinker such as Nietzsche, the most important source for Vitalist culture. For Nietzsche, Socrates was the enemy, a ‘symptom of degeneration’, suppressing instinct and denying the immanent life force – the very root of Vitalism – in favour of absolute rationality.31

Zahrtmann, in contrast, is a wholly Socratic thinker, concerned with the ethical relationship of the self to itself. While he certainly rejected obedience to a normative moral code, Zahrtmann always presented an acute awareness of the need for a positive personal ethics, as in his paintings of Catholic ritual, or Biblical scenes, or of historical subjects in which moral choices are played out. This position may be closer to that of Høffding; while Høffding’s work was an important source for Nietzsche’s thought, his moral position opposes Nietzsche’s so-called ‘great man morality’, with its rejection of social norms, resting instead on the ‘welfare principle’, a critical form of utilitarianism that might shape the discussion of a moral problem rather than prescribe its solution.32 Zahrtmann shared not only Høffding’s enthusiasm for Socrates, but also something of this welfare morality; he explained in a letter to fellow artist Otto Haslund in 1889, that he considered it a good thing not to be able to get whatever one demands and that ‘happiness is not being cared for, but caring for others’.33

If not a Vitalist, Zahrtmann has also been presented as an aesthete, concerned, like Bang, with beauty, decoration, and the pleasures of refined domesticity, with its effeminising effects. Certainly, the opulence of his studio was widely reported, and Zahrtmann’s own paintings emphasise this [Fig.7]. In his memoir, Harold Moltke described the painter’s ‘beautiful atelier, where rich furniture, carved Renaissance chests and his own paintings in wide, carved frames gave the room its gilded, priceless atmosphere’.34 Similarly, Moltke’s wife, Countess Elsa, called the studio ‘an Aladdin’s cave’, adding a hint of Oriental decadence, perhaps.35 These tropes of luxury, exoticism, and sensual richness resonate in the many newspaper reports.36

Morten Steen Hansen reads the interior and the artist’s concern for beautiful objects and effects as related, in some degree, to the discourse of perverse Aestheticism, and thus a partial feminisation of the artist’s identity, and one that resisted the masculine norms of Vitalism.37 Zahrtmann, however, is very much not the model of the aesthete. There is widespread admiration for the luxury and aesthetic allure of the atelier, in the press and elsewhere, with not a hint of distaste. The studio was perceived as an external expression of the great man’s artistic prowess and a material record of a life devoted to art. Moreover, the interior, furniture, and collecting are all very male pursuits, particularly in the context of the artist’s studio around 1900. Zahrtmann has much in common with contemporary artists elsewhere, such as William Merritt Chase in New York [fig. 8] or Lawrence Alma-Tadema in London, who constructed their studios similarly as Aladdin’s caves, domestic spaces filled with eclectic beauty and tactility and the exotic. These artists are in no way feminised by their surroundings, even if the interior could be used by homosexual men as a means of shaping and expressing their identity.38

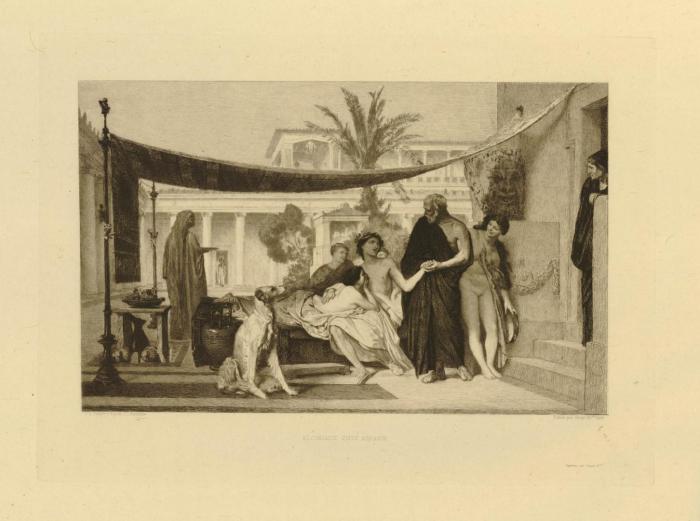

Nevertheless, the specific motif of Socrates and Alcibiades clearly makes the connection with homosexual desire. It would have been possible to present the Symposium with a less overtly sexual theme, for instance, in portraying one of the other characters, such as Agathon, or in picturing the scene of Greek debate more generically, emphasising the mise-en-scène and intellectual and material environment. Similarly, a different moment from the life of Alcibiades could have been selected, such as the famous incident of Socrates’ removing his disciple from the clutches of a female courtesan, as had been painted by Gérôme and numerous other artists; a scene that insists on Alcibiades’ heterosexual desire [fig. 9].

If one wants to postulate a connection between Zahrtmann and the morality scandal, there is a concrete link: Hjalmar Sørensen, the model for Alcibiades. Sørensen, whom Zahrtmann described as an ‘excellent model’, posed for Zahrtmann in Copenhagen and then travelled to Italy with him in 1911, first to Pisa and thence to Civita d’Antico where Zahrtmann summered with friends and pupils.39

Sørensen wished to become a painter and in return for modelling had painting lessons from Zahrtmann. He modelled not only for Alcibiades, but also the Mandolin Player and Henry V in the painting of Henry V and his Sister (of which biographist Danneskjold-Samsøe comments ‘the woman is of no interest to Zahrtmann, while the portrait of Sørensen is warm and alive’).40 While Zahrtmann believed at first that Sørensen had the making of a painter, his experience in Italy changed his mind and Zahrtmann curtailed his tuition.41 Nevertheless, Sørensen went on to build a modest career as a painter, exhibiting regularly at the Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling from 1914 and at the annual spring exhibition at Charlottenborg from 1919. He also had his own exhibition of paintings and studies at the art dealer Anton Hansen’s in 1919.42 Most famously, he painted the ceiling of the Officers’ Pavilion at the barracks in Hvidovre, south of Copenhagen [fig.10]. The ceiling demonstrates the impact of Zahrtmann, in the use of Homeric motifs, the colour, and the shaping of the male nude. Moreover, it also includes a version of Prometheus and the Eagle, which is clearly modelled on Zahrtmann’s painting of the subject.

Sørensen was directly involved in the events of Great Morality Scandal. Between 1897 and 1903, he lived with Carl Albert Hansen, the extraordinary policeman and proletarian novelist who was one of the scandal’s best known victims.43 While Hansen was arrested, tried and imprisoned, not least perhaps because he was a member of the city police, Sørensen was not. He was, however, interviewed many times, as were some members of his family. The interviews reveal a collision of two very different conceptions of homosexual desire. The chief concern of the police was the morphology of the acts undertaken by Hansen and Sørensen: did they only engage in mutual masturbation or were they guilty of the ‘crime against nature’? There is a legal reason for this definition of homosexual activity through forms of bodily coupling: two distinct crimes existed, the crime against nature (§177) or the lesser charge of gross indecency (§185). Nonetheless, the records show a strangely prurient line of questioning, which went beyond the nature of the sexual act, and probed for detail: were Hansen (?) and Sørensen lying down or standing up; how exactly did their bodies interact?44

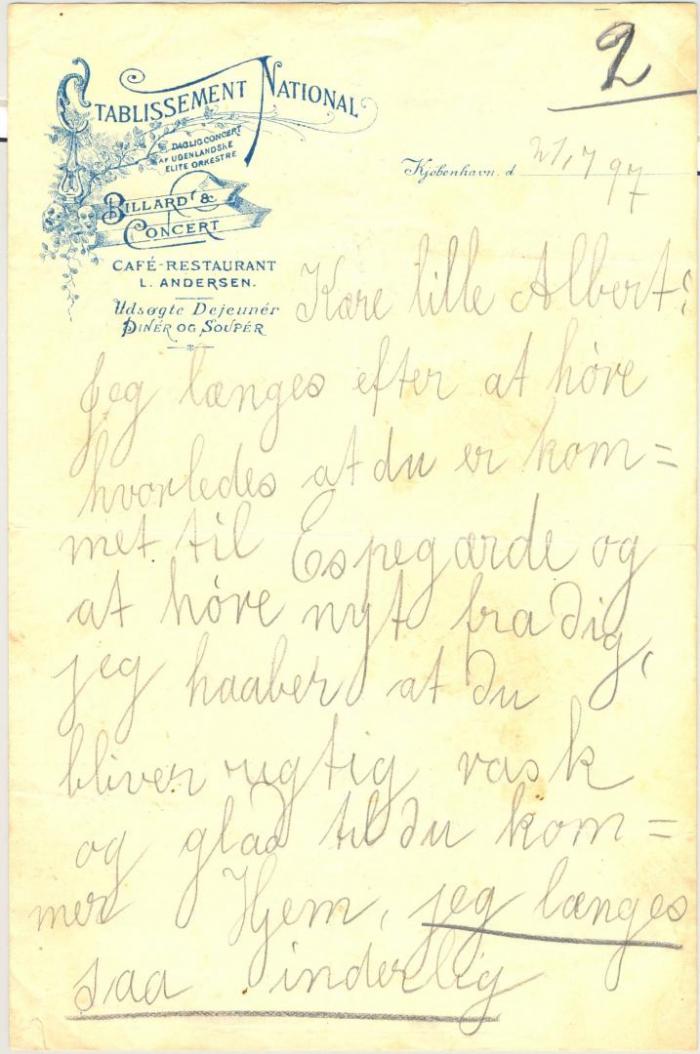

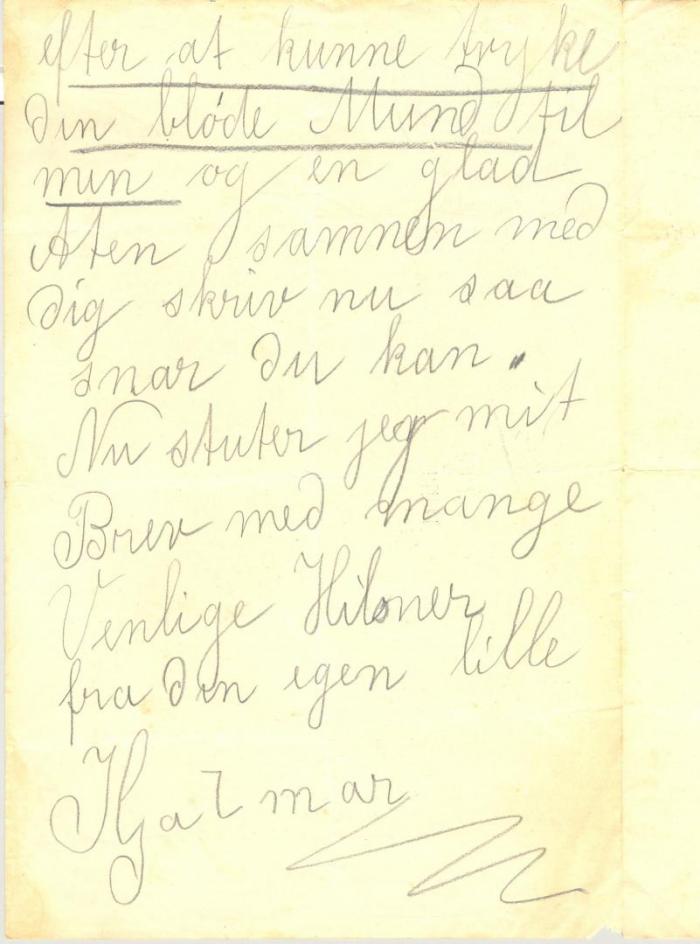

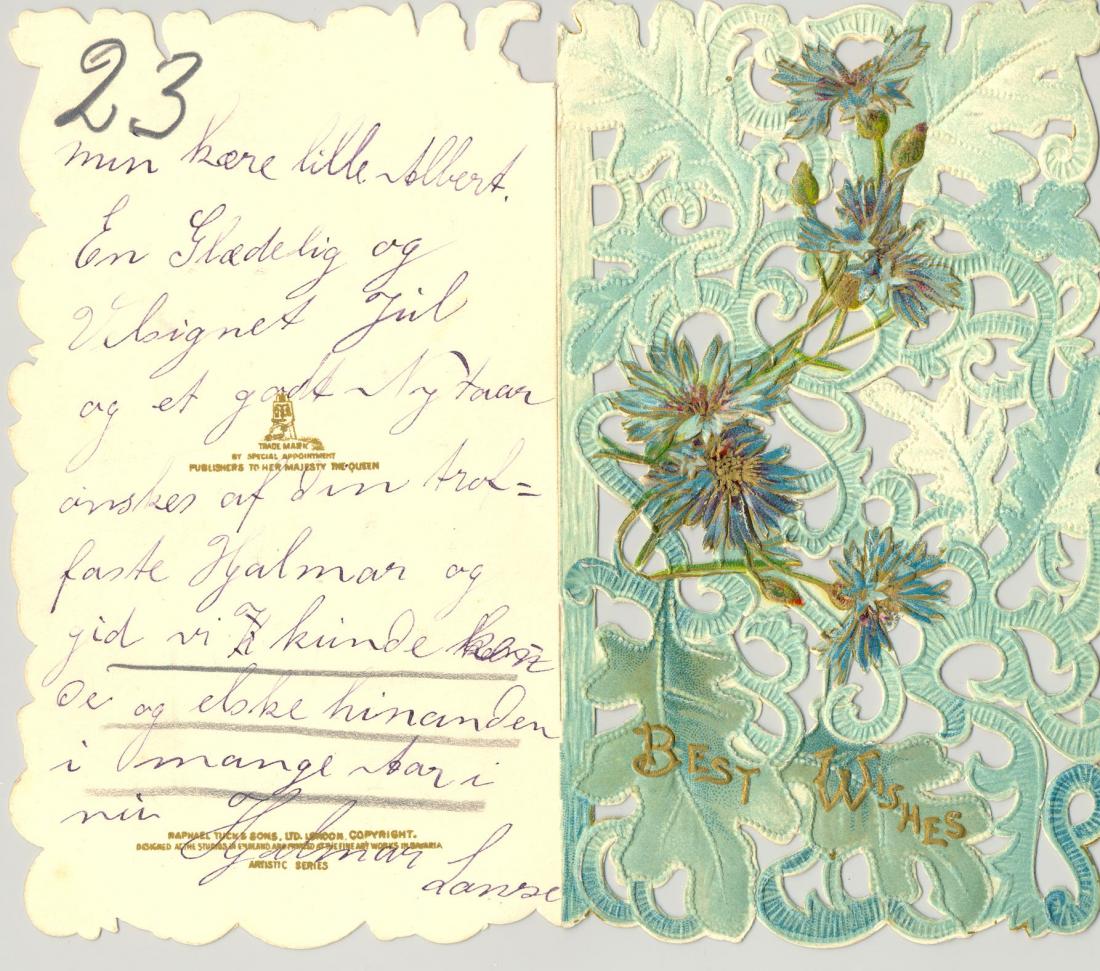

The prosecution of homosexual men, including Hansen, was also supported by the use of documents seized during raids by the police; letters, diaries and photographs, which might be used as incriminating evidence. There is cache of letters in Rigsarkivet taken from Hansen’s home, which includes correspondence between Albert and Hjalmar. What is striking is that the letters reveal love; the homosexuality of the scandal, marked by degeneracy, exploitation, and prostitution, is displaced in these documents by affection and domestic life [fig.11]:

I long so deeply to press your soft mouth to mine and spend a happy evening with you write as soon as you can […] with many friendly greetings from your own little [lille] Hjalmar.45

The use of the word ‘lille’ is not insignificant. The word means ‘little’, but as saying ‘dear little Albert’ and ‘from your little Hjalmar’ would suggest in English, this is a sentimental attachment. Similarly, Hjalmar signed a Christmas card to Albert in 1897 ‘From your faithful Hjalmar’ followed by the wish that they might love each other for many years to come [fig.12].46 One can see where the police agent has underlined such incriminating details. The line made by the detective’s pencil is evidence of a different kind, of the official insistence on an impermeable boundary between homosexual degeneracy and heteronormative love.

The archival documents reveal a fascinating story of cruising, love, sex, and attempted suicide, and this story cannot be told here. Nor do we know if Zahrtmann knew of Sørensen’s past. We nonetheless have the tantalising fact that Hjalmar was facing police interviews in 1907, and a few years later was in Italy with Zahrtmann.

History Painting as Ethical Practice

The paintings of Socrates and Alcibiades are embedded in these two contexts. While the pictures draw together licit antiquity and illicit sexuality, more importantly they challenge the very framework that distinguishes between them. For rather than the Hellenistic fraternity of Vitalism or the Aestheticist embrace of deviance, Zahrtmann presents a distinctive third option, one which turns to Plato’s Symposium as an ethical alternative to these more duplicitous or more radical representations of male bonds and homosexual desire. Zahrtmann takes the Symposium seriously as philosophy, using it not only as a topic, but engaging with its arguments. As such, an analysis of the painting needs to begin with a brief summary of the Symposium.

The crucial parts of Plato’s discourse on eros are the speeches of Socrates and Alcibiades, which explore the relationship between incarnation and transcendence. Socrates’ speech quotes the words of Diotima, a fictional female priestess, who describes the ascent from the physical experience of human love to the overcoming of it in the search for knowledge of the truth. This ascent begins with the love of a beautiful individual, moves to the love of beauty in general, thence to the love of moral beauty, and finally, the goal, to wisdom, the Ideal Form of Beauty. After Socrates’ has spoken, Alicibaides famously arrives drunk and disorderly. In his speech, he details his attempts to seduce Socrates and his failure to do so, presenting Socrates as exemplary of Diotima’s theory. While Zahrtmann’s 1907 painting is closer in spirit and subject to Alcibiades’ story, the 1911 version engages with Socrates’ philosophical position. In both, however, desire is not conceived in terms of an act, the physical form of bodies coupling, but about the relationship of a man to another and to himself.

At the heart of Zahrtmann’s artistic approach, and particularly his representation of desire, is his wish to continue the great tradition of history painting. While his style, particularly his use of colour in his later works, and his institutional associations position him with the avant-garde, his artistic project is Janus-faced, aiming above all to retain the significance of history painting and its moral force; that is, to eschew the merely illustrative, and to reinstate history painting as an ethical form. In a letter to the artist Joakim Skovgaard, in 1886, he remarks that ‘[…] it is often the way with us weak men, that we are drawn towards ethical goals by way of aesthetics.’47 While Zahrtmann wished, as prominent art historian Julius Lange had remarked of Poussin, to ‘repair the ethical attitude of history painting’, he did so with a decisively modern and in some respects ahistorical approach.48 Socrates and Alcibiades, while modest in size and form, exemplifies this, although, as we shall see, this ethical urge is by no means straightforward.

Contemporaries were aware that Zahrtmann’s history painting was unusual. Writing in 1922, director of the Hirschsprung Collection Emil Hannover remarked that Zahrtmann ‘read history in a different way from most men, with more fancy and more vision’.49 Hannover decribed Zahrtmann’s approach as emotional rather than rational, unconcerned with historical accuracy, adding: ‘Perhaps it was just because he knew a great deal about such things thaat he frequently took liberties with them’.50 Similarly, art historian Karl Madsen, in an article in Kunst in 1904, pointed to the way in which Zahrtmann subverted the tradition of history painting: ‘His characterisation of historical figures is regularly in conflict with customary representations.’ For Madsen, this was as an institutional challenge which presented ‘in a style far from Frederiksborg’, that is, outside the accepted norms of the genre and its protocols for the representation of national history seen at the museum of the Frederiksborg royal castle.51

This nature of this challenge is implicitly, and at times explicitly, revealed in contemporary discussions of Zahrtmann and his work. As a major cultural figure, he was widely discussed in the press, regularly appearing in the pages of newspapers, with details of his comings and goings, his exhibitions, his homes, birthday celebrations and teaching, and much more besides. Through this mass of reportage, two particular tropes are repeated over and over again. The first is ejendommelig, his peculiarity in the sense of what is most characteristic and idiosyncratic, but also what is strange. It is not a wholly uncommon word in late-nineteenth-century art criticsm; Madsen, in his Kunstens Historie i Danmark of 1907, uses it to identify the idiosyncratic aspects of several artists’ styles.52 However, it does seem that, rather than one of many words used in art criticism, it is the first adjective critics and writers reach for when discussing Zahrtmann. Moreover, critics use the work not only in accounts of Zahrtmann’s painting but also in descriptions of the man himself and his personality.53 The second frequently used term is ‘paradox’. Again, this is deployed to describe his style, his nature, his colour sense, and even the source of his wisdom.54 Madsen argued that, in the last period of his career, Zahrtmann became ‘the master of paradox’.55

Neither the ‘ejendommelig’ nor the paradoxical are qualities traditionally associated with history painting. The ‘Frederiksborg style’ demands a more concrete sense of the past, and often a clear political position; the contradictions of history may be exposed, but are generally presented in an ostensibly objective and unparadoxical manner. Both terms, however, may lead towards a “queer” reading of Zahrtmann’s work, and towards recognition that it is this “queerness” that his contemporaries regard as his greatness. Towards the end of his life, there were criticisms from a number of art critics about his use of the model. An obituary by Jens Pedersen in Bornholms Social-Demokrat (but syndicated to a series of other Social Democrat newspapers) asserted that Zahrtmann was unable to free himself from the actuality of the model and raise the body to become a Socrates or an Alcibiades.56 Similarly, some critics saw Adam as no more than a naked man, rather than the Biblical figure the painting purported to show.57 Most scathing of all, a critic reviewing the Zahrtmann retrospective that constituted a large part of the Free Exhibition that year, castigated the 1907 painting, describing Socrates as a lusty old drunkard and Alcibiades as the most vulgar of modern bruisers.58 These criticisms, however, rather than identifying Zahrtmann’s failure, highlight his objective, even his success. He did not wish to efface the modern, physical presence of the model, to transform the present into the past. Rather, he wanted to represent a tension between past and present; not just the spiritual life of the past that Pedersen thought ‘a stranger to him’ but also the physicality of contemporary life. How might the flesh lead to the spiritual? How might the aesthetic lead to the ethical? These questions required an acknowledgement of the tension between the fleshly model and the historical ideal

Zahrtmann’s rethinking of history painting is also evident in the humour of both paintings. In the 1907 version of Socrates and Alcibiades, emphasising the distinction between Alcibaides’ famed beauty and Socrates’s yet more famed ugliness, Socrates’ laughter suggests his playfulness, as well as the irony of Alcibiades’ desire. The 1911 version reformulates this comic irony, showing the beautiful Alcibiades’ attempt to seduce the ugly Socrates through the subtle leaning in of his body and his wry expression. Zahrtmann’s witty take on history is evident in other paintings; the picture of Queen Christina in Rome, her large manly hands hoisting up her skirt to warm her bottom at the fire, while smoking a pipe, is perhaps the work that comes most readily to mind [fig.13]. Such humour is a further trope commonly used by critics to describe Zahrtmann’s work and personality.59 Emil Hannover, discussing Zahrtmann’s approach to history, remarked that the artist ‘was not above coquetting with his reputation […] he liked to paint anything that made good people wonder whether it was in jest on in earnest’.60 This image of coquetting, of Zahrtmann as a seductive flirt toying with the viewer and with history, is a loaded metaphor, to say the least. This coquetting may seem trivial; indeed, it threatens to trivialise the most earnest of all genres. However, this is part of Zahrtmann’s aesthetic radicalism; like Ræder’s Socrates, speaking ‘half in jest, half in earnest’, the artist challenges the boundary between the serious and the comic.

This positive good humour has a direct bearing on the representation of sexuality, for this is a decisive move away not only from the familiar representation of the homosexual as a tragic figure. The tragic underpinned much medical and psychiatric thought, which conceived homosexuality as an inborn disease, often discussed alongside paranoia, kleptomania, and epilepsy as part of the taxonomy of mental illness.61 There is some evidence that homosexual men internalised this model. Bang, writing to his brother-in-law in March 1893, called his sexuality a ‘curse’, and, in line with contemporary medical views, talked of ‘we, who from birth are burdened with this disease – for that is what it is’.62 The standard representation of the homosexual in novels, even sympathetic ones, is equally dismal. In For Guds Aasyn, published by Bang’s secretary Christian Houmark in 1910, homosexuality is an inherited curse that can only lead to exile and the prospect of a hopeless life.63 Of course, many a homosexual man did buckle under the weight of persecution and fear, but mental disturbance was more likely a result of attitudes to homosexuality rather than caused by sexual identity. There were certainly disagreements within the medical profession. Erik Pontoppidan, for instance, very strongly opposed the idea of homosexuality as a disease.64 Nevertheless, the association of homosexuality with misery, social exclusion, and a life of torment was widely accepted.

Against this discourse, Zahrtmann displaces pity and pathos in favour of playfulness and pleasure. Pleasure, again, is a regular trope in contemporary discussions of Zahrtmann’s art, and one that has a particular bearing on sexuality. The body is less a burden than a field of possibilities. Bodily pleasure is a favoured theme, as in the painting of Christina of Sweden lifting her skirts and warming her buttocks in front of the fire; or pleasure yet to emerge, as in Adam is Bored (alternate title: Adam in Paradise), with its suggestion of a sexual future. Sexual desire is not something to be suppressed for Zahrtmann, but something to be problematized, that is, to be considered, woven into the fabric of daily life, used productively within limits. The 1911 painting of Socrates and Alcibiades is exemplary of this, and it is to the detail of the painting that I now turn.

Sculpture and Skin

In reframing history painting, Zahrtmann thought deeply about his art’s relationship to the great tradition. There is a very clear connection, particularly in the 1907 version of Socrates and Alcibiades, to Eckersberg’s painting of the same subject from around 1814 [fig.14]. Zahrtmann considered Eckersberg one of the greatest of painters, and would certainly have seen this painting in Thorvaldsens Museum.65

Eckersberg’s painting depicts Alcibiades, rapt with attention, as Socrates talks to him. Jesper Svenningsen has recently argued that Eckersberg’s history paintings revolve around the exchange of looks and hands, rather than grand theatrical gestures.66 Here, the hands and the looks enact the shift from desire (Alcibiades’ nudity and his attempt to seduce Socrates) to philosophy (Socrates’ good-natured renunciation), from body to mind. In the 1911 version, Zahrtmann reconfigured the elements of Eckersberg’s painting, and mimicked his economy of visual means. Certainly, surface, colour and framing are all very different, but this is intended less to disrupt the great tradition of Danish art, and more to draw out what is already there, excavating from Eckersberg’s painting the possibilities of desire and its management or containment.

A yet more important reference to art tradition is the use of sculpture in the 1911 version. Socrates ignores the beautiful muscly Alcibiades and instead studies the statuette he holds, the ideal figure of the Tübingen Hoplitodromos Runner, a late archaic, Greek statuette of an athlete from around 485 BCE.67 More than just provoking a paragone of flesh and sculpture, the inclusion of this statuette makes a specific reference to the Symposium. Alcibiades begins his speech with a description of Socrates, whom he compares to statues of the ugly Silenus, which can be opened to reveal a beautiful god inside. This uncoupling of the internal and the external disrupts a more familiar sculptural notion of the body as a moral index, in which physical beauty and ugliness signify moral status. Moreover, this tension between inside and out, between object and idea, is articulated in Alcibiades’ speech. Alicibiades offers sex in return for Socrates’ wisdom; Socrates tells him that he is trying to get true beauty in return for mere appearance, which the philosopher characterizes as ‘bronze for gold’.68

Sculpture, or the sculptural body, is also pertinent as perhaps the most common means of visualizing male homosexuality around 1900. More than any other art form, sculpture embodies the homoerotic. By homoerotic, I mean the boundary between licit appreciation of and pleasure in the male body by other men and the illicit.69 The connoisseur of antique sculpture is required to admire, to understand the erotic force of the object, but he has to constrain this admiration lest the threshold of the homoerotic be crossed and actual desire, rather than an abstract formulation of desire, be mobilised.

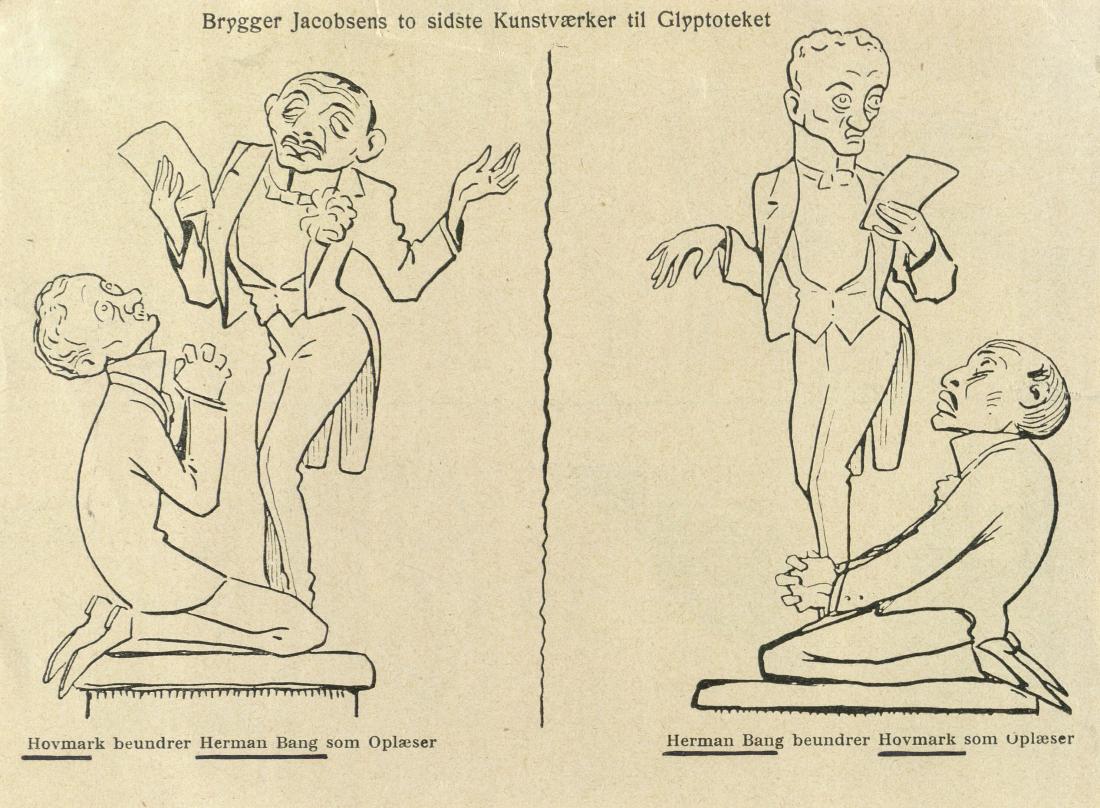

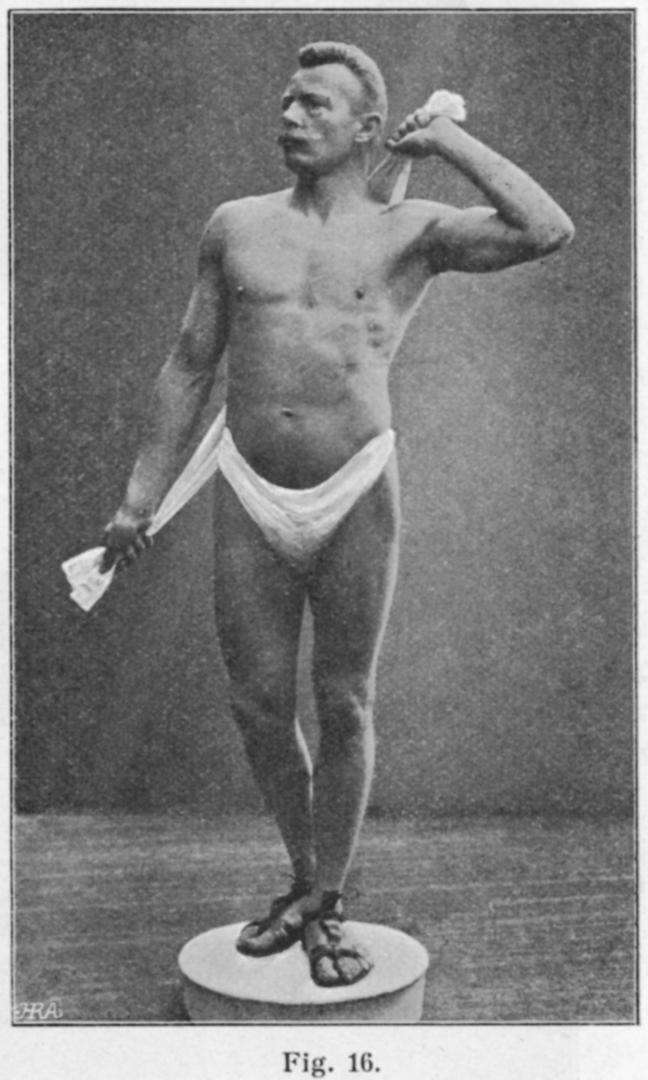

The use of sculpture to organise a taxonomy of homoerotic looking is characteristic of early-twentieth century Denmark. A cartoon from 1906 of Bang and his secretary Christian Houmark represents the pair as the latest acquisition in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek [fig.15].70 The Glyptothek had recently purchased Stephan Sinding’s Adoratio [fig.16], and this becomes the template for a familiar caricature of the homosexual, marked by intense narcissism and deluded notions of beauty. Houmark worships Bang, and Bang worships Houmark, with the idealised forms of Sinding’s sculptural bodies replaced by the weak and degenerate forms of homosexuality. (And of course, the Morality Scandal is the means of understanding what is going on here.)

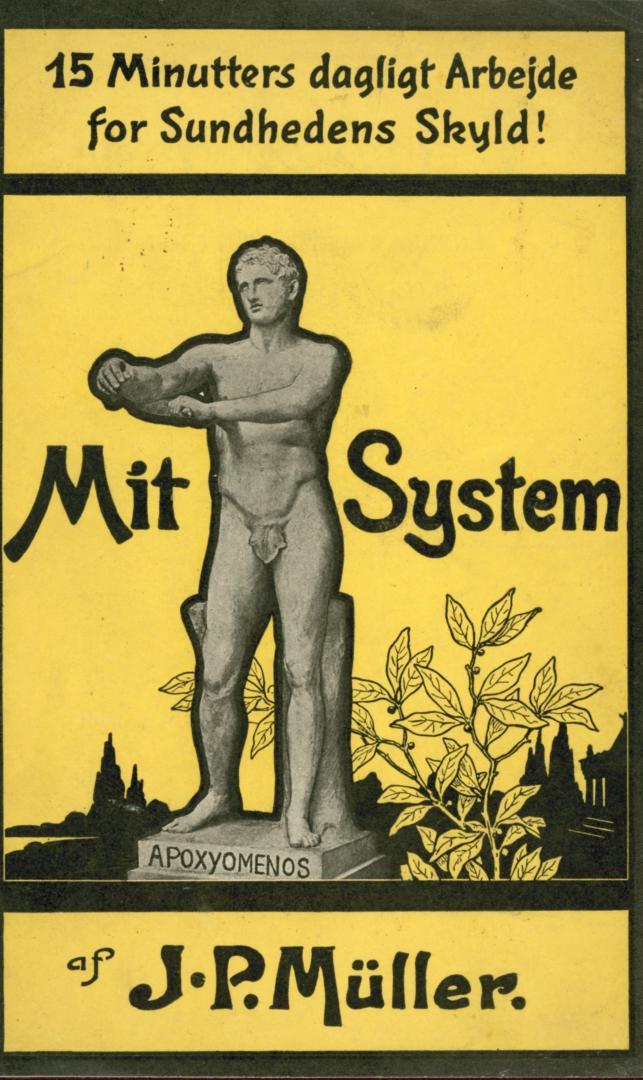

On the other side of the homoerotic boundary, we might consider the physical culture guru J. P. Müller, who had such extraordinary success across Europe with his system of exercise, first published as My System in 1904.71 Müller presented himself as the well-known Apoxyomenos by Lysippos, and here the statue graces the cover of the book, an exemplar of beauty if looked at in the correct way [fig.17].The Apoxyomenos is an ideal of male beauty that can be understood to transcend the bodily; its abstract poise turns attention away from the physical. Müller contrasts the statue with ‘repulsive pictures’ of the strong man, remarking ‘How supremely calm, how dignified and superior, and how delightfully harmonious, in comparison, the antique classical figures are!’72 This is a direct attack on other physical culture gurus, notably Eugen Sandow’s emulation of the Farnese Hercules, and so is in part motivated by market competition. Yet it is also about maintaining the correct relationship between viewer and body, a relationship that must not sink into adoration, ignoring the hunt for the inner ideal in the worship of outward physical form.

Socrates’ consideration of the statuette is embedded in this matrix of exteriors and interiors, a matrix that Zahrtmann complicates. This small sculpture is not a straightforward image of the body that is desired; indeed, it disrupts desire in the composition. In handling the object but not looking at it, and in turning away from the desirable body of Alcibiades, pushing towards him, Socrates turns desire into a philosophical question; the statuette symbolises the problematization of desire, that is, its nature and its place in ethical practice.

Moreover, Zahrtmann re-thinks the relationship between skin and surface. Müller’s regime had as one of its key principles the care of the skin, and it required the rubbing of the body to stimulate health; hence the choice of the Apoxyomenos. This rubbing of the skin, which Müller termed ‘skin gymnastics’, was central to the regime:

One can lay it down as a rule that the good or ill treatment of the skin has an immediate effect on the whole general state of one’s health. The skin is not a sort of impermeable covering of the body, but ‘is in itself one of its most important organs’.73

This took place both as part of exercise itself, during which movements involved the rubbing of the skin, as well as in bathing and the use of a towel to clean and invigorate the skin, as in this photographic illustration from the book [fig.18]. Like the polishing of the marble surface, this emphasised the skin as boundary between self and world. The skin is a site of experience, for sure, and tactility, whether literal, as in towelling, or imagined, as in the viewing of marble or bronze, is a hinge where self and world meet.

Zahrtmann’s conception of surface differs. He is just as acutely attentive to the skin, but in his paintings the body’s surface becomes a more complex matter, mutable and subjective rather than the abstract and objective boundary of ideal skin. And while sculpture, in marble or flesh, locates tactile experience on the skin, Zahrtmann spreads eros and experience across the surface of the painting, as if the world itself is the site of subjective tactile experience. It is evident throughout his work, in the treatment of fabrics and other materials, in hands reaching or touching, and the constant promise for the viewer of pleasure and disgust. But it is also evident in the paint itself, which insistently threatens to break away from its referents, as if it were an experiential veil spread over the surface of the world. One can see this in the way he paints Alcibiades, for instance in the light on the pectorals, where he layers colour and light, using wet paint over dry, to create something both solidly fleshly and yet shifting, a surface as yielding as soft skin and as polished as bronze.

This is also a question of colour, the most distinctive and most discussed feature of his practice, particularly in later years.74 The colour in Socrates and Alcibiades is typical of Zahrtmann’s later practice, not least in the way that the dense network of coloured marks becomes more complex as one approaches the painting. From a distant viewpoint, the colour seems unexceptional, but, as one gets nearer to the surface, it starts to dissolve into specks of blue, red, turquoise and other colours, flickering across skin and fabric. Particularly striking is the emergence of the bright red of Alcibiades’ nipples, and the deep crimson of shadows, as if something of the body’s interior were being glimpsed. Again, this is less evident from a distance, and swims into view with closeness; as if the intimacy between viewer and painting parallels the intimacy between the two bodies. The relationship between colour and the object is, of course, subjective, and here again Zahrtmann eschews the objective in favour of a history painting that opens up to time and desire. Thus, while, for Müller, the skin is a continuous and stable topological surface, Zahrtmann paints the skin as motile, a surface constantly changing and generating pleasure, just as the surface of the painting, the skin of the image, does. The unsettling of the relationship between touch and sight is represented explicitly in the painting. Socrates, in contemplating the statuette, is not actually looking at it. His hands move over the surface while his expression registers a profound inwardness. This is not a paragone of painting and sculpture, but of touch and thought, or of the aesthetic and the ethical.

But the statuette that Socrates holds is not the only sculptural object in the scene. Zahrtmann has also included, in the top right hand corner of the painting, his own sculpture: Leonora Christina Leaving Prison [fig.19]. He began modelling this in 1905, and exhibited it for the first time in the Free Exhibition of 1910. The sculpture is a three-dimensional version of the central group from his painting of Leonora Christina’s release from prison, and was reproduced in various materials [fig.20].75 This statuette was Zahrtmann’s plastic interpretation of what can only be termed an obsession with Leonora Christina, the daughter of seventeenth-century monarch Christian IV. At the age of fifteen, she was married to the statesman Corfitz Ulfeldt, as part of an attempt by Christian to win the loyalty of powerful nobles by marrying his daughters and bestowing dowries. When Frederik III ascended the throne in 1648, Leonora and her husband were deemed enemies by the new king and his wife. As a result of much intrigue and political rivalry, during which she refused to betray her husband, Leonora was imprisoned for twenty years through the 1660s and 70s. During her solitary confinement she wrote a memoir, A Memory of Lament, which was finally published in 1869. The book became the foundation of Zahrtmann’s history painting, and he painted many scenes from Leonora’s life throughout his career.76

This model of Leonora Christina Leaving Prison further disrupts the orthodox configuration of body, homosexual desire, and sculpture. What is a modern statuette of a seventeenth-century noblewoman doing here in an image of ancient Greece painted in the context of contemporary Denmark? I would like to suggest three things:

First, like the Phrygian bonnet worn by Eckersberg’s Alcibiades, Leonora is a symbol of freedom. This is not a radical political conception of freedom, as the bonnet is, but a more ethical conception. It is literal freedom, in that her imprisonment is over, but also a freedom of or from the self; what Zahrtmann admired in Leonora, and what is emphasised over and over again in his paintings, was her self-mastery. She represents a different version of Diotima’s ascent, from the physical to the transcendental. In the painting of her death from 1897, he painted Leonora as if transfigured, more like the Virgin Mary than a seventeenth-century aristocrat, her body dematerialising into hazy spirit in contrast to the very solid and fleshly figures surrounding her [fig.21]. Leonora’s presence in Socrates and Alcibiades suggests that the Symposium is not about the gratification of desire, but, as argued in Socrates’ speech, the understanding of love beyond the individual.

Second, the presence of the statue disrupts time and space in the painting. This telescoping of history is analogous to the structure of the Symposium. While it reports a single event, the Symposium has a very complex temporal structure: Plato relates what his narrator, Apollodorus, reports of speeches made by others, including Socrates’ recounting of what Diotima had told him. Zahrtmann’s visual chains can be seen as equivalent in presenting an understanding of love and virtue that is transmitted through different sources across time. As such, it is also a means of avoiding a direct link between the antique and the contemporary.

In Eckersberg’s Socrates and Alcibiades, Alcibiades sits on a contemporary klismos chair, similar to those designed by Abildgaard in 1790 [fig.22]; but this is very much an idea of antique furniture recreated, based on historical sources. Zahrtmann gathers up history differently. He often adds such objects to historical scenes, deliberately creating temporal and spatial discontinuity in order to disrupt the mise-en-scène and to challenge us to make sense of these juxtapositions. For example, he inserts both the Leonora statuette and his bust of Leonora into the painting of The Prodigal Son, exhibited at the Free Exhibition in 1909, along with other objects from his studio, including a Hellenistic Egyptian relief, an altar-like cloth and a painted screen [fig.23]. This is unlike the standard practice of artists who used studio objects as historical props to suggest an authentic picture of the past or another culture. Zahrtmann uses these objects in an antithetical manner, collapsing time and space by means of deliberate anachronism. The tale of The Prodigal Son, the drama of desire and duty pivoting on the tension between morality as a law to be answered and morality as personal redemption, takes place, effectively, in Zahrtmann’s own studio.

It is in this use of anachronism that we see the peculiarity and paradox of Zahrtmann’s history painting most explicitly. Here he is at the farthest remove from Frederiksborg and the tradition in which he is both locating himself and rejecting. His concern is not to offer a pictorial moral lesson, but to trace an ethical thread through history, the practices of self-formation or self-reflection that continue to concern human life. Writing to the painter August Jerndorff from Greece in the winter of 1883-4, Zahrtmann explained:

There is a rich opportunity to study Leonora Christina here, for all the sculpture has the same great innocent calm luminosity as her.77

The idea that the study of Greek sculpture is a means of studying Leonora Christina may seem bizarre, but it rests on Zahrtmann’s conviction that any part of history is best understood comparatively, not through an archaeological probing into a single moment, but through a genealogical sequence, an unfolding which includes himself, from Greek antiquity, through early modern Denmark to contemporary Copenhagen. Here is what Hannover sees as characteristic: the reading of history against the grain, the ‘fancy and vision’, taking liberties and coquetting with history as subjective desire is interwoven with historical fact.

Thus, Zahrtmann does not name or picture Socrates in the way that, say, Oscar Wilde did, to assert a direct equivalence between past and present.78 Instead, Socrates stands as an exemplar of how to find a place for oneself in the world and in history, how to reconcile desire with other ethical concerns. This is a reminder too that male and other bonds across history, between past and present, are fantasised in complex ways, and these imaginary or identificatory transhistorical bonds are always about the relationship of the self to itself.

Zahrtmann/Socrates

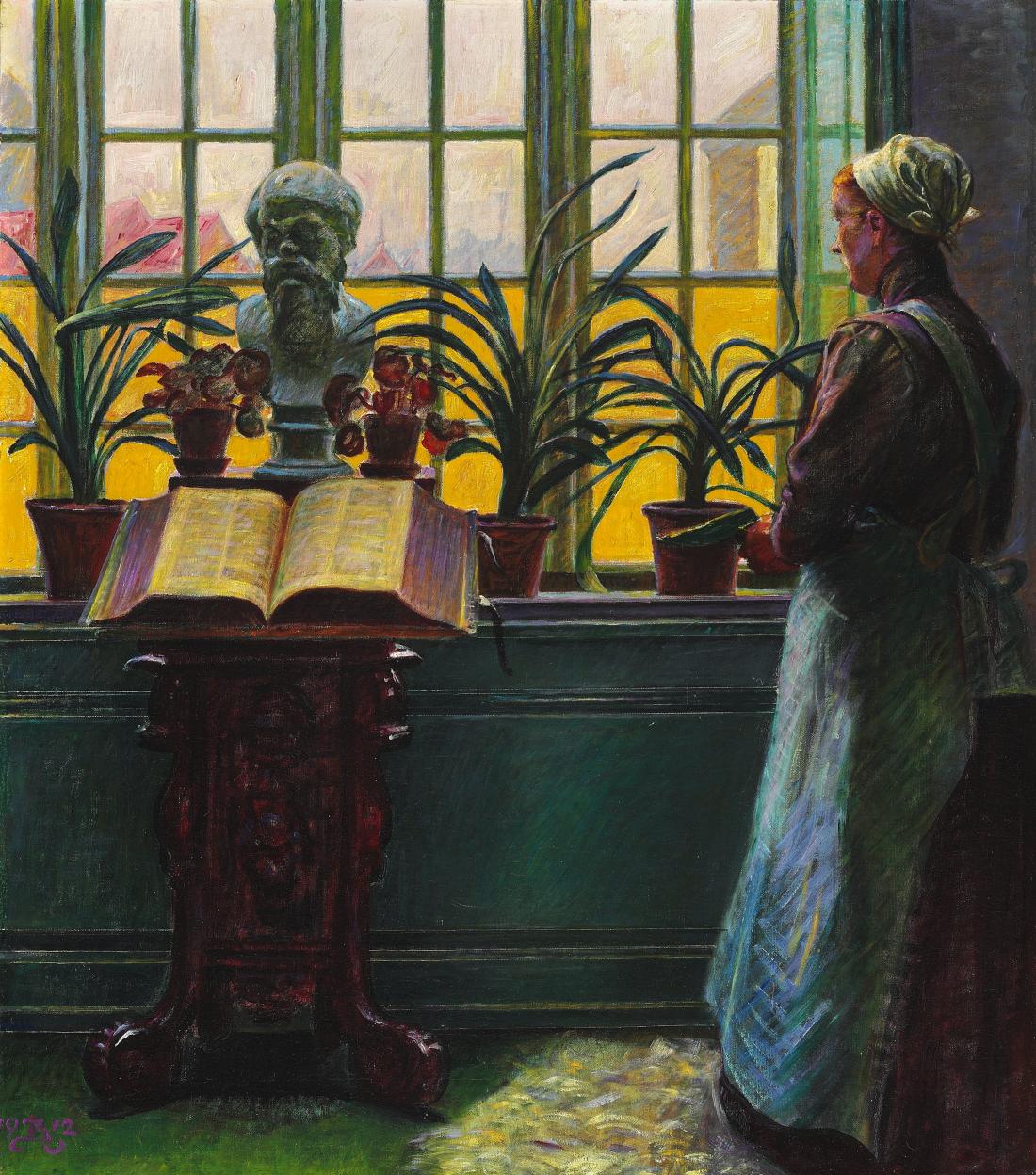

This leads us to the third reason for the inclusion of the statuette of Leonora Christina in the painting. This is Zahrtmann’s way of putting himself in this picture. Leonora may serve as a surrogate for Zahrtmann, but, more importantly, I wonder if she becomes his Diotima. Like Diotima in the Symposium, Leonora is a character who is only quoted in the painting, and yet serves as the moral centre. By extension, Zahrtmann is representing himself as Socrates. This Socratic self-vision is found elsewhere in Zahrtmann’s work. At the Bible Table, the first painting he made after moving into his new home in Fuglebakken in Copenhagen in November 1912, shows his studio, with an old Bible opened on its stand and his plaster bust of Socrates in the window [fig.24]. The only figure in the painting is his housekeeper, but Socrates surely stands here for Zahrtmann himself.

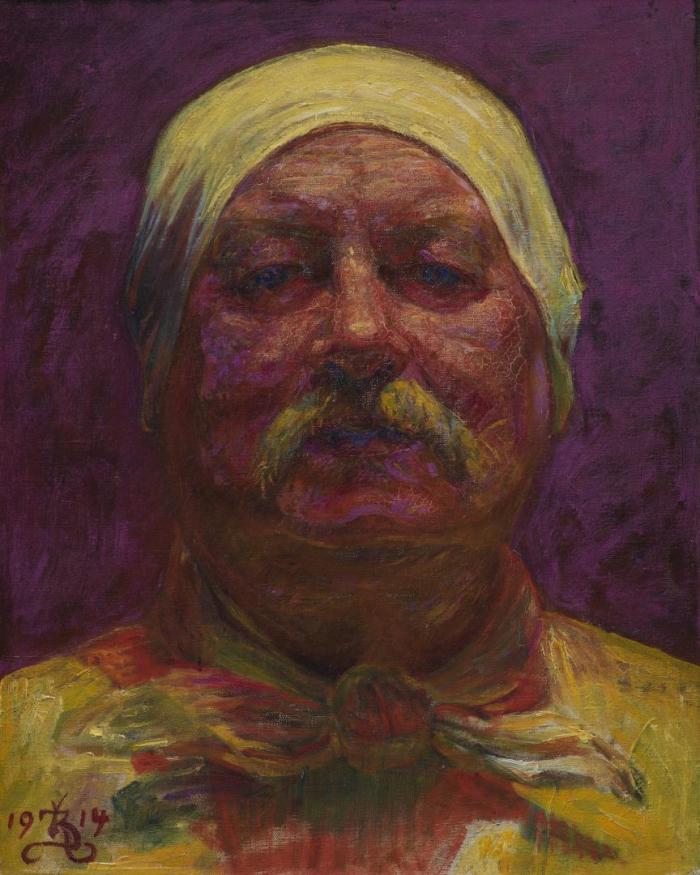

Like the extensive series of self-portraits he painted at this time, representing himself close up over and over and over again, the bust, which is the template for Socrates in the painting, remained in his possession [fig.25-26].79 The bust almost forms part of the sequence of self-portraits, which constitute a Socratic process of self-examination. Here again the concern for the ethical self and its relationship to desire is explored as the painter ages and contemplates his incarnation. The self-portraits clearly demonstrate Zahrtmann’s love of Rembrandt, but they are not a straightforward imitation of familiar practice. Instead, these are what Foucault calls ‘a technique of the self’, that is, a practice which through repetition provides a means of shaping or understanding the relationship of the self to itself.80 If the rubbing of the skin in skin gymnastics is a technique which forms the body as an exterior, here a different sense of surface is produced by the laying of the paint on canvas, the staring into the mirror, the intense self-scrutiny: the self as maker, subject and viewer at the same time, these roles both united and separated. Again, what we witness here is neither the Vitalist’s concern for the inner dynamic essence, nor the Aesthete’s sense of outward performative display, but a problematization of these ideas. Danneskjold-Samsøe remarks that ‘while Zahrtmann in his earlier years diligently let himself be photographed, he painted in his later years a large number of self-portraits, which later came to have a prominent place in his art.81 Like Socrates meditating on the statuette, Zahrtmann meditates on his own relationship to desire as he ages.

I would not want to suggest that Zahrtmann sees himself as Socrates as a self-aggrandising move. This identification is, rather, a means of thinking about the relationship of the aesthetic to the ethical, how his life as a teacher and artist might accommodate or productively engage with desire. Again, the specific context of Denmark’s cultural life in the early years of the twentieth century might lend support to this. There is an interesting juxtaposition with the work of Julius Lange, the great Danish art historian, who was so important to the development of scholarship on antiquity, and whom Zahrtmann knew throughout his life. In the posthumously published book The Human Figure in the History of Art, published in Danish in 1892–1899 and in German in 1903.

. Lange placed Socrates at the root of Western art. Lange begins his discussion of what he sees as a watershed in the representation of the human figure, with a long quotation from Xenophon’s Memorabilia, in which Socrates defines art as the expression of the life of the soul. It is in this claim, Lange argues, that Socrates discovers subjectivity, and that this conception of subjectivity emerges from the relationship between Eros and Beauty: ‘[Eros] is woken by Beauty […] and, on the other hand, Eros awakens beauty’.82 Moreover, Lange also says of Socrates’ definition, ‘[t]hese words have a resonance and a certain eroticism’.83 He proceeds to explain that, for Socrates and the Greeks, Eros was exemplified by the love of an older and younger man; that the noblest form of Eros in ancient Greece was the desire of one man for another. This was the root of art, and therefore, the root of understanding the life of the soul.

There is a kinship with Zahrtmann’s work in the idea that the sexually desiring self does not simply find its erotic object, motivated by bodily need, but that the erotic is a starting point for self-formation, a more truly Socratic position. All this opens onto another aspect of the Symposium: fathering and immortality. Diotima’s account of the relationship between Eros and immortality distinguishes men who father children and men who are ‘pregnant in mind’ rather than body, giving birth to ideas or monuments rather than sons and daughters in order to press for immortality. For the former, the child is borne out of love with a beautiful woman; for the latter, the source of love and procreation is a beautiful younger man, whose ethical education bears wisdom and virtue.

Zahrtmann’s pedagogy was certainly in line with this. As is well known, he established his own art school, the Artists’ Study School, which contested the academic method by fostering a kind of ‘know thyself’ approach, asking each student to develop his own way of painting rather than conforming to a particular style.84 Peter Hansen, one of Zahrtmann’s most important students, wrote a short memoir of his time at the school in Tilskueren in 1913, as part of a feature celebrating Zahrtmann’s seventieth birthday. Hansen describes the school as ‘anarchy, where each of us claimed our personal freedom’. He goes on:

He sought to teach us our skills, our natures, not just through the work in the school, but also in our work outside it. In his eagerness to get to the heart of us, he became acquainted with our financial situation and our other private relationships, even the most intimate things, which for him were important for understanding us.85

It seems that Zahrtmann’s pedagogy focussed on the students’ relationship to themselves, their understanding of themselves and how they might work to develop that selfhood. As teacher and mentor, Zahrtmann saw his role as moving beyond the mere practice of painting, but considering that practice as a means of forming and reforming the self. It is not only aesthetic work, but also ethical work. His contemporaries clearly understood this and made it explicit in accounts of the school. Emil Hannover, writing in 1922, noted that Zahrtmann ‘had a general moral influence, for his examples encouraged many others to be themselves and themselves only’.86 Similarly, Karl Madsen asked that Zahrtmann be thanked for his moral example, for his care and concern for his pupils in the school, ‘where the students could experiment, doubting and finding themselves’.87 Here again, the ethical is about knowing and being true to oneself, about the internal reflective work of self-formation rather than the judgment of external actions.

As part of this ethical education, each summer Zahrtmann took favoured pupils such as Poul S. Christiansen and Peter Hansen to Italy, as was also the case with Hjalmar Sørensen. This was part of the personal structure of education that extended beyond the school and its classes. This is not about intergenerational sexual relations, although it does have a bearing on the erotics of pedagogy. Writing to Otto Haslund from Greece, when visiting in 1889, Zahrtmann remarked how he was drawn to young men – but adding in an emphatic parenthesis ‘as a teacher’.88 Even earlier in his career, we see him reflecting on his sexuality in terms of a Socratic position, one that does not ignore the erotic, but deploys a conception of eros more in line with the Symposium. It is part of his, in many ways, conservative and certainly patriarchal position, whereby homosexual eros awakens beauty and beauty awakens this eros.

I have referred to the pupils generically as ‘he’ because women were not included. Other scholars have revealed Zahrtmann’s patriarchal attitudes and the limits of his attitude towards women.89 An earlier painting, exhibited in 1903, depicted Socrates and Xanthippe, the familiar myth of the poor put-upon philosopher and his shrewish wife.90 Similarly, Countess Else Moltke testifies to Zahrtmann’s sexism in her memoirs. Moltke describes how she would attend artists’ conversations in Zahrtmann’s home in Fuglebakken, but while the men participated in the symposium, she would have to remain silent, sitting under the red silk screen bending over her sewing, in order to create a beautiful effect of blonde hair in crimson light.91 This is the reverse of Zahrtmann’s self-portrait using the red silk screen, which probes the inner man rather than reducing the body to desirable surface; and yet a portrait in which Zahrtmann places himself in a different light, literally and metaphorically, to pose the question of how his art, his desire and his selfhood are related.

The juxtaposition of Socrates and Xanthippe and Socrates and Alcibiades shows the two sides of his patriarchy: directed against women and directed towards young men. Plato’s Symposium is used to support this patriarchal perspective. There were, of course, women whom Zahrtmann loved and admired, not least his mother and Leonora Christina, and there were women he painted over and over, most famously Madame Ullebølle, who served as the model for many historical figures. These models of femininity are, like Diotima in the Platonic dialogue, exceptional, and removed of any erotic charge; they feature in the understanding of the erotic rather than the experience of the erotic.

Conclusion

On the one hand, then, Socrates, Alcibiades and Diotima, on the other hand, Zahrtmann, Sørensen and Leonora: this painting is neither the Vitalist ethos as an alibi for admiring the male body, nor the aesthete’s particular vision of Platonic love. Instead, it elaborates the homoerotic, that boundary that marks out the legitimate and the illicit, the pleasure that can be taken and the pleasure that cannot. Zahrtmann walks this line, not in order to express homosexual desire in a straightforward manner, but to use that desire to generate his history painting, his role as a teacher, his public reputation and cultural power.

Zahrtmann used the Symposium to visualise a response to the scandal of 1906 that offered a different lesson for the homosexual man. The task was not just to see one’s desire mirrored in history, but to understand history as a means of forming the self, of problematizing desire in order to achieve wisdom or happiness, an ethical injunction that might be revisited in an age of identity politics. Of course, we have no documentary record of how Zahrtmann actually read the Symposium. Nevertheless, the painting does provide a visual analogue to Diotima’s theory: the ascent towards the ideal from beautiful individual (Alcibiades), to beauty in general (the statuette), to moral beauty (Leonora) and thence to a dream of wisdom and immortality. Like Socrates, half in jest, half in earnest, Zahrtmann’s painting acknowledges the seductive flesh and its pleasures only to renounce it in his own ethical vision of bronze for gold.

Thanks

I would like to thank Rasmus Kjærboe and Lene Østermark-Johansen for their invaluable help with this article.